“We know that we are living in a crisis,” states Mathias Klenner, one of five members of the Santiago-based architectural collective TOMA. “We also know that the neoliberal political and economic system is so deep inside our minds and inside our bodies that we cannot think of any solutions. And yet you see that sometimes people have actually managed to gather together, like in the Occupy movement. But the question is: how do you create possibilities? How do you think about the future? And how do you connect these different groups of people?”

For TOMA, and many other politically-oriented architecture studios today, one possible tactic involves so-called “urban interventions”, or any of a variety of lightweight, typically short-term design actions that target specific sites in a city. Sometimes referred to as ‘tactical urbanism’, ‘interventionary urbanism’, or ‘urban acupuncture’, such practices have become increasingly prevalent in recent years, gaining attention in publications and online, and surfacing in cities around the world. But the practices themselves are far from cohesive in intent or effect, ranging from the ornamental to the political. And, even when there is a stated political aim, efficacy proves disparate and contestable. Yarn bombs aren’t the same as a territorial occupation, and it’s hard to say if either actually affects the administration of the city on any substantial level, let alone the systemic inequity built into it.urban spaces have always been tweaked for political reasons

In any case, urban spaces have always been tweaked for political reasons. But by and large, these are top-down manipulations: planters installed in public squares to prevent large assemblies or cameras affixed to telephone poles. This makes sense—after all, it’s the ‘top’ that has legal control of the city, not to mention access to funds. Bottom-up, protest urbanism rarely involves designers. Stacking up cars to form a barricade doesn’t require a degree in architecture. There’s a structural complicity between architecture, as a practice of building, and existing power systems—two pyramidal forms mirroring and touching one another. So attempts to counter this dynamic usually begin with widening the pool of collaborators and experimenting with the role of the architect.

“We work a lot [towards] making these kind of projects approachable, understandable and owned by all the rest of people involved,” Enorme, a Madrid-based studio that practices “tactical urbanism” alongside more traditional work, told me via email. “That means to make them porous and adaptable.” For example, in 2014, they took part in the “Espacios de Paz” program promoted by PICO Estudio in Venezuela, which coupled foreign architecture studios with local ones to produce urban interventions for five different sites. Specifically, they were tasked with renovating a site in Las Tres Marías, a neighborhood of Pinto Salinas in Caracas, that had been polluted with garbage and unfiltered water. Alongside renovating the water system, the project involved a lightweight roof structure that transformed the area into a public space.From design phase to final construction the process of the project became a collective matter

For Enorme, a significant aspect of the project was its inclusion of a diverse array of constituents, from neighbors to official institutions. “From design phase to final construction the process of the project became a collective matter in which the teams of architects took a role of proposing the frameworks for the dialogue between all parties concerned,” they state.

“We are convinced that every small action that is carried out in the margins of ‘official urbanism’ has most of the times a great political value, no matter the duration and scale,” Enorme continue. “It is of course very remarkable when this type of action gets to involve a lot of people, whether these people agree 100% or not about the implications or the way of acting, and also when they last long, when they transform along the way.”

While Enorme’s work involved a tangible transformation of a site, other urban interventions tend toward the ephemeral. In such cases, their results are less easy to quantify—but that’s exactly the point. Cities, some practitioners would argue, are much more than their physical form. “We believe that all people have a right to the city, this is the right to spontaneity and surprise, to moments of community and conflict, to and [sic] exchange of cultures and ideas and many, many other things,” state ON/OFF, an international network of designers, architects, curators, filmmakers and urbanists.We believe that all people have a right to the city

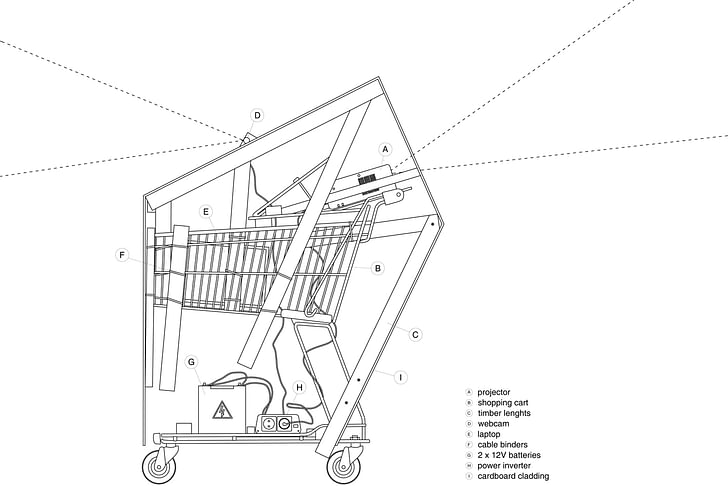

One of their recurrent modes of engagement they call “co-machines”, or ad-hoc mobile structures intended to connect people to each other and to the city. In Berlin in 2012, ON/OFF made their first “co-machine” called the Kopfkino, which translates in German roughly to “mental image”. Using a borrowed shopping cart as a structure, ON/OFF built around it a shell and inserted a camera, a projector, and a car battery. The Kopfkino was carted around the city, recording images and projecting them much larger on to adjacent buildings. “The Kopfkino became from then on an open-ended, collaborative experiment, whereby people using the streets were able to broadcast or perform, transforming their everyday surrounding into a stage set,” ON/OFF tell me over email. “The Kopfkino was chanced upon passers-by and used a kind of fiction and mystery to engage people in a fleeting moment of surprise in their daily routines.”

“[Co-machines] employ disruption—blocking, diverting, sabotaging, re-programming, communicating and accelerating—to distort and render visible particular processes and actors within the city,” state ON/OFF. The “co-machines” are both social activators and rhetorical devices at once. Through constructing new relations between individuals within an urban community, these interventions expose the existing patterns of social isolation and atomization. In that, the “co-machines” achieve their critical rhetorical function: to suggest what could be is to articulate what is not already. Like research devices, they are used to find new potentials for urban experience. ON/OFF describe their “co-machines” as “physicalized questions”, intended to critically address perceived deficiencies in the city. They “put forward provocations”, but ON/OFF are clear about locating their political limitations alongside their potential.To make any meaningful impact on the city you must employ both scales of action (strategic and tactical)

“Co-machines operate at the scale of a tactic in the city. They rarely have a strategic dimension. To make any meaningful impact on the city you must employ both scales of action (strategic and tactical), and therefore co-machines are only one tool of those available to designers and the public to engage in the conversation on what cities should be,” ON/OFF states.

“Like many young design collectives, ON/OFF has used small scale, immediate and improvised methods to participate in a debate on the city, which is dominated by vested economic and political interests. It would be naive to suggest that a small, temporary intervention or action in a public space could make any meaningful change to the structural issues affecting the city, but this doesn't negate the political value of co-machines. They are intensely political manifestations, and have an important role in the ongoing, healthy critique of the city.”

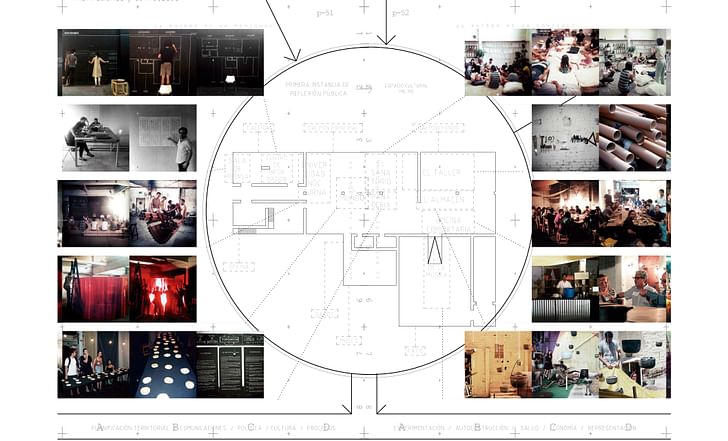

For ON/OFF, co-machines are “tests” or “prototypes” rather than solutions, an idea that resonates with TOMA, who also, incidentally, started in 2012. Like with ON/OFF and Enorme, TOMA’s work encompasses a diverse set of practices, not just interventions. Their first significant project, “La Ocupación”, which involved the temporary takeover of a building in Santiago, helped the group understand some of the strengths and limitations of such practices. Over the course of six days, TOMA facilitated the construction of a “temporary city”, comprising eight “institutions” developed by different collectives that published newspapers and produced programming such as workshops, talks, and dinners. This all occurred in a soon-to-be-razed warehouse building in the midst of what would become a development.We are perpetrators as much as observers

Santiago is, in some ways, the archetypal neoliberal city—a literal testing ground for the economic policies developed by the infamous Chicago Boys, who studied under Milton Friedman at the University of Chicago. Following the U.S.-backed coup of the socialist President Salvador Allende in 1973, Chile was ruled by the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, who deregulated the economy and privatized state-owned industries. Wealth was concentrated; social ties severed; alternatives foreclosed. “La Ocupación” and its “institutions” were intended to mirror the organization of the neoliberal city, while proposing new potentials for social interaction through experimentation. How could new forms of collectivity be constructed within the contemporary context of Santiago?

“One of the good things about [La Ocupación] was that it was indeterminate,” states Klenner. “It was out of control constantly because we didn't create a way for this temporary society to work, we decided all together—all the people that participated in creating the institutions—how it would be. But then when it was actually working, we didn't know at all what would actually happen.”

For TOMA, the project succeeded on many levels—it brought people together, fostered discussion, and many of the ‘institutions’ continued after the building was demolished. But equally as important for TOMA was where it fell short. Eduardo Peréz, another member of the group, explained that the project ended up fueling the success of the development, which was marketed as a hip, art-oriented mall (of sorts). “We are perpetrators as much as observers,” he notes. “That’s something we increasingly think about.”Architecture wants—or architecture needs—to recover its political dimension

“[Such projects] are really easily absorbed. [They] become part of the language of neoliberalism or whatever you want to call it,” Peréz explains. “What I'm asking myself right now is how do you get rid of this absorption. What do you have to do? You have to be very very fast in order to move faster than the possibilities of absorption. Or you have to be extremely radical. Or... I don't know.”

“Architecture wants—or architecture needs—to recover its political dimension, but you cannot do it working in the classical way you do architecture,” states Klenner. “So you need to find other ways. And urban interventions are part of it, but [they’re just one part of] a much bigger struggle for architecture to recover its position as a discipline that wants to talk about how we want to create our world today.”

This feature is part of Archinect's November editorial theme, XS.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.