“Hospitals, water and electricity are always the first to be attacked,” states a doctor from Anadan, a city in Northern Syria, as quoted in an Amnesty International report. “Once that happens people no longer have services to survive.”

In spite of international law, civilian infrastructure has become a major target of aerial bombardments by both the Assad regime and some rebel forces during the ongoing conflict in Syria. But according to Sigil, an architecture collective that investigates the larger, symbolic history of infrastructure in the conflict-ridden country, this isn’t the first time that infrastructure has been weaponized there.

Sigil comprises Khaled Malas, who formerly worked as an architect before pursuing his PhD in Medieval Studies; Salim al-Kadi, who runs a small office in Beirut; Jana Traboulsi, an illustrator and graphic designer; and Alfred Tarazi, a visual artist. With their project for the Oslo Architecture Triennale, entitled Monuments of the Everyday, Sigil collaborated with Ala Tannir, an architect and industrial designer by training, as well as architects Alia Bader and Antione Soued. Piecing together key events in the infrastructural development of Syria, Sigil analyzes its role as a symbolic buttress for past regimesPiecing together key events in the infrastructural development of Syria, Sigil analyzes its role as a symbolic buttress for past regimes, and imagines possible forms for monuments created by the counter-hegemonic power of ‘the everyday’.

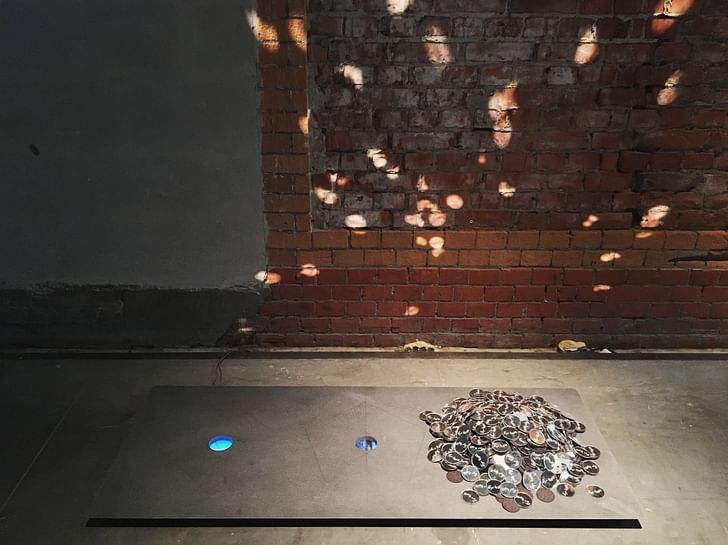

Sigil’s project was represented at the Oslo Architecture Triennale by a small panel placed on the ground, with videos describing the three-part Monuments of the Everyday projected from underneath through small holes. Previous iterations of the project have been exhibited at the Venice Biennale and the Marrakech Biennial. Taking advantage of the institutional support facilitated by this exposure, Sigil gathered resources to strategically intervene in their research by producing actual infrastructural objects: a well and a windmill.

I talked with Sigil at the Oslo Architecture Triennale to learn more about their project.

Can you tell me about the project you’re showing in On Residence?

Khaled Malas: This is the third iteration of a series of projects called Monuments of the Everyday. The first one was called Excavating The Sky and looked at the role of the airplane in producing the landscapes of Syria, either through observation or bombing, over the course of the last century. As a response to that we were able to build initially one well, and then a second well, in parts of the country where the regime had destroyed the water infrastructure. Then, with an activist group called the Higher Commission for Civic Defense, we were able to first of all renovate an existing agricultural well and then plug it into the existing village infrastructure. And so for the first time in I think almost two years—a year and a half—people switched on their taps in their homes and they had water.

Wow, that’s incredible.

KM: And nobody knows where the water is coming from, except for these twenty amazing guys that work with us. I don’t even know the exact location of the well.for the first time in I think almost two years people switched on their taps in their homes and they had water

Is infrastructure specifically a military target there, or is the damage collateral?

Salim al-Kadi: Yeah, it’s always a target.

KM: By the regime and by some of the rebel forces, but in this particular case it’s the regime that used airplanes to bomb the existing water structure.

And are you building the wells for the rebel forces?

KM: No. We’re building it for the civilians because what happened in this particular area is, when the regime collapsed there, these armed militias came in and took control of the area. It’s moved from a very clear, single oppressor with a very clear apparatus—because they wear uniforms and they have insignia and stuff like that—to a bunch of different [ones], many of them unnamed militias that are just patrolling the streets. [The militias] were selling the water to the local population to make up for this lack [caused] by the regime. I know someone, an old friend of mine who was one of the founders of this group, and so, in cooperation with him, we were able to do this project.

What part of Syria is it in?

KM: It’s in South Syria in an area called Daraa. It’s not so far from the Jordanian border.

And was it an active war zone when you were working there?

KM: We weren’t physically there, it was [the Higher Commission for Civic Defense] who was there. We did very basic project management type stuff and provided the funds. Basically, we were able to secure the funds by applying to different art grant type agencies and trying to sell this almost like an art project. It was a reaction to your typical scenario where monuments are sticking up into the sky, while this one’s firmly rooted into the groundThe fact that it was exhibited at the Venice Biennale meant that a lot of people were actually interested in it because it was a prestigious show, so they were interested in having their logo up on our wall in Venice. In Venice we had a weeklong series of sessions. We screened five or six different films, we had a panel one day and we had one very big drawing—it’s about 9 meters x 4 meters on the front and another 4 x 4 on the back—that is a representation of the project.

Which Biennale?

KM: This is during Rem [Koolhaas]’s Biennale, this is 2014.

SaK: What’s great about the well is the way it’s connected to the existing infrastructure. The water is for free—it cannot be sold because it just keeps on running. That’s also an important point for me.

How is it hidden?

KM: It’s completely clandestine. The actual hole is 6 cm (2½ inches) so essentially it’s impossible to find. Literally it’s just a hole and then it was covered with a stone. [...] The whole point was to tie this into this larger narrative about power that’s falling from the sky and the manners in which different forms of oppression, particularly by the state, try to occupy the sky and then drop power from it. It was a reaction to your typical scenario where monuments are sticking up into the sky, while this one’s firmly rooted into the ground. Talking about a different form of power which is not only present on the surface of the ground, but also is rooted into the landscape itself.

Very interesting.

SaK: And a different form of monument.

KM: In that project we told four different stories. The first is the story of the first airplane to fly in Syria in the months preceding the first World War. The Ottomans wanted to show that they were on top of things and they have this new machine called the airplane, and so it went on a propaganda tour with a big carnival in Damascus to celebrate the arrival of the pilot, the copilot and this airplane. And then three hours after it takes off it crashes and the pilot and copilot die somewhere in what is now the occupied Golan Heights. The government in Istanbul sends in another plane because this obviously is a very big embarrassment; it flies to Damascus as well. This time it’s much more subdued because the city is in mourning. It flies, takes off, goes to Jaffa in occupied Palestine and the story is that they had a bit too much to drink at lunch and so they crash in the Mediterranean. One of them dies and the other survives. The three are given a hero’s burial in Damascus next to Saladin, the great anti-crusader. That’s the first story.

The second story is the story of the French bombing of Damascus during the Mandate era. Very few people know this but Damascus might have the honor of being the first city to be carpet-bombed, which is basically when you drop as many bombs as you can, kill as many people as you can with as many planes as you can. So we had a revolt against the French Mandate and it was a revolt that spread throughout the country very, very quickly. Someone had this idea to drop all these bombs at the same time and they destroyed a part of the old city. They destroyed many parts but there’s a particular part that was hit very, very heavily and that area till today is called the Blaze, the name of the neighborhood. Damascus might have the honor of being the first city to be carpet-bombedAnd what’s interesting is in the League of Nations, when it was argued about whether you can do this, the French [...] argued that this was a planning intervention and it was some kind of civilizing process. They superimposed these aerial photographs of the city with these very clean, modernist lines on top of it and said….

SaK: It’s a grid.

KM: It’s a grid, basically, and they claimed this was in fact a planning intervention. Look how dirty and squiggly the streets are, look what we’re going to give them. And so we’re using the airplanes to produce this. Tabula rasa, basically.

The third story is from 1987. We had a cosmonaut that was sent up with the Soviets. The first live televised conversation on Syrian TV was between this cosmonaut and our president at the time, Hafez al-Assad, where he describes the landscapes of Syria, tells how beautiful it is. You have to imagine this man in this tin can in the sky talking to the President. And there’s a very solemn video of them speaking with one another.

Then he drops down from the sky and he’s decorated with every single medal the Syrian air force has, et cetera, et cetera, and then he disappears for forty something years before he announces his defection in 2012. Apparently he had gone back into the Syrian air force. He’s from Aleppo and when the Syrian air force began to bomb Aleppo he chose to defect. [This was] one of the earliest defection videos in 2011-2012 when things were just starting.

The final story there was the story of the barrel bomb. You know what a barrel bomb is? It’s an improvised explosive device that has a long history but has particularly been put to great use by the Syrian regime. we tell a particular story of a particular barrel bomb that falls into a toilet and a man’s poem in response to this.It’s basically an old oil barrel that’s filled with old shrapnel and maybe some TNT, maybe a cooking gas canister. What you do is you take a bunch of them onto a helicopter, and then you light a fuse, almost like in a cartoon. We have a video of a guy doing it with a cigarette. And then you just push it out.

It’s completely inaccurate, it kills many people and it’s probably claimed thousands and thousands of lives and destroyed thousands and thousands of villages and neighborhoods over the course of the last five years. We tell a particular story of a particular barrel bomb that falls into a toilet and a man’s poem in response to this. Because he had a little latrine that he built in this field and in this example the barrel bomb falls into the latrine, you have to imagine like shit and porcelain went flying everywhere and then this man chooses to commemorate this moment with a poem challenging the regime that tried to control his shit and also his speech. For me, this is a very profound reflection of where we are as a people, revolting against multiple forms of oppression.

Then the fifth story is what I [already] explained to you: the story of the well, which is a reflection, if you will, upon the powers of the sky.

And you were saying it’s connected to the windmill project as well?

KM: Yeah, so the windmill project was the first one. All of these projects are called Monuments of the Everyday. The windmill project is titled Current Power in Syria, and that project looks at electricity as a nation-building device across a very similar hundred year period where again we tell four stories about how electricity has formed the nation. Electricity is like this invisible force that manifests itself either through practitioners or infrastructure or appliances. So we’re very interested as architects in trying to dismantle this and so, again, we tell four stories.

The first one is the story of the telegraph, it’s an Ottoman telegraph, the first electrical infrastructure in our part of the world. It’s the story of a particular sheikh, like a clergyman, who in some really small town at the edge of the desert which is now in Jordan, wakes up one day and there’s a telegraph office outside of his door. He’s like ‘what is this?’, and they explain to him how this thing works. We’re very interested in the long, deep history of how these different technologies work—and also how they are resistedHe is very intrigued because in his town he shares his dreams with everyone; whatever he dreamed the night before, he lets people know what it is. It’s explained to him that he can actually send his dream to Istanbul, directly to the palace. So he wakes up every morning and sends a telegraph to the Sultan telling him what he dreamed last night because he feels that this is very important information for the Sultan to know. Of course he’s completely ignored, but the only reason this exists in the archive is because at one point he dreams of an assassination attempt and when that happens every single Ottoman, bureaucrat/soldier between Istanbul and his town, Sult, is mobilized to get to the bottom of this assassination attempt dream. That’s our first story.

Our second story is a story of a tram strike. This is again during the Mandate area, when the Belgian electrical utility company who ran the trams and the street lamps in Damascus decided to raise the fare of the tram half of the currency. So half a piaster, which is like the equivalent of half a cent. The citizens were not happy with this, and a strike erupted. The strike soon took over the entire city and then the entire country and became this very famous event in the history of the anti-colonial struggle called the '60-day Strike', which was a 58 day strike that covered the entirety of Mandate Syria and also parts of Palestine and Lebanon throughout, and Egypt. The economy came to a complete standstill and the French were forced to negotiate with the Syrian politicians about independence. This is 1938. So the Syrian negotiation team goes to Paris and they sign a treaty called the Franco-Syrian Treaty of Friendship and the French gave us our independence basically. Unfortunately that’s just before Hitler rolls into Paris and so everything is postponed until 1944, when we actually do get our independence.

We were very interested in how this kind of popular strike actually leads to independence, because obviously all these stories that I’m telling you have very clear repercussions to what’s happening today. We’re very interested in the long, deep history of how these different technologies work—and also how they are resisted. So the telegraph was not designed for a dream to be communicated but in a way that dream is part of our own resistance to this technology. That’s the second story.

[the] failure of the modernist, socialist project in this particular landscape and how it quickly transformed into a very particular form of oppressionThe third story is a story of the dam and it’s told through the eyes of Syrian filmmaker called Omar Amiralay, who just died a couple of years ago. He returns from May ‘68 Paris super excited about wanting to be a part of his country and the socialist revolution that was happening there. The only job he could really get [involved] this gigantic infrastructural project, the Euphrates dam. It’s the largest development project in the history of Syria. It went on for like 30 years maybe.

They are like okay, you want to make a film? Go and make a film about the building of the dam. And so he makes this gorgeous, gorgeous movie called The Film-Essay on the Euphrates Dam (1970) that basically looks like a Russian constructivist film where you have all these machines going around, concrete being poured, people moving and then contrasted with very simple village life that’s in the area. It’s very difficult. For example, there’s a scene where a man is building a wall and he asks him like how long will it take you to build this mud brick wall. [The man responds], ‘oh, it will take me six days’. And then he cuts to this gigantic concrete pour. It’s amazing.

33 years later he makes a film called A Flood in Baath Country where he regrets what he understands to be a propaganda effort, and he goes back to the same site and begins to pick out the multiple forms of oppression that he recognizes, particularly in the school. One of the main characters is a school principal and how he’s teaching the kids and treating them. It’s like this failure of the modernist, socialist project in this particular landscape and how it quickly transformed into a very particular form of oppression.

The fourth story is torture. It’s about the use of electricity in torture in Syria as a citizen-building mechanism. Because, of course, we’re all afraid of being captured by the regime and being tortured and because, obviously at this point, it’s become all very infamous because of the war, but it’s been going on for a long time. [Since] it’s a very heavy topic, we talk about it through a very popular comedian called Ghawwar al-Toshi. You have to imagine, Ghawwar is a bit of a Charlie Chaplin-like tramp on the stage. Then the plays are filmed and they’re broadcast repeatedly on Syrian TV. This is one of the ways in which the citizens were allowed to vent a little bit.

In this particular scene that we’re interested in, Ghawwar is captured for a crime that is not very clear by two secret policemen and they use multiple forms of torture on him. They waterboard him, they slap him around a little bit and every time they do this, he somehow manages to subvert it in a way and the entire theatre erupts in laughter. Then, when nothing works, the secret policemen goes 'okay, we’re going to use electricity'. And so as soon as they stick in the plug into the outlet [Ghawwar] begins to laugh. He’s shaking and he’s laughing hysterically and when he is asked why he is laughing—and the entire theatre just goes silent; it’s a beautiful, beautiful scene—he’s like, ‘oh well, I’m really sorry sir to be laughing but electricity arrived in my asshole before it arrived in the village.’ And so this is another form of that [trope of the] failure of the potential of electricity that also subverts it.I’m really sorry sir to be laughing but electricity arrived in my asshole before it arrived in the village.

I met this person online, his name is Yaseen al-Bushy. He’s a 25 year old architecture student who lives in a village just outside of Damascus. Not even a village, it’s like a suburb. It used to be a village, but now because of the informal spread of the city it’s probably, practically speaking, part of the city. And this is a part of the country that has been cut off from everything. There’s a barricade around it, so people are not allowed in or out, food is not allowed in or out, medical supplies, et cetera, et cetera. And in addition it’s being shelled.

What people are doing for energy is they have discovered this technique where they collect pieces of plastic from either rubble or from garbage, melt it down in these very primitive furnaces and capture the fumes. If you capture the fumes at a particular temperature you get a substance that is not benzene, but is very similar to benzene, and you can use it in stand-alone generators. If you do it at another temperature you could actually get a substance that is very similar to diesel. This provides 80% of their energy needs. It’s obviously very toxic for the people doing this; it’s also very toxic for the environment, et cetera, et cetera.

Yaseen introduced me to this man called Abu Ali Al-Kalamouni, which is his nom de guerre if you want. Abu Ali is a blacksmith who was sick of the system, and he has this agricultural canal out of his blacksmithery shop that is now practically an open sewage canal. He built a waterwheel like a noria—which has a very long history in Syria—out of metal scrap that was lying around in the shop. [a mirror] is a kind of architectural type that is easily recognizable but also has the ability to mean multiple things to multiple people at different timesBy tinkering around with it, he was able to provide power for his shop and for his house. I became very, very interested in this and in collaborating with Yaseen and with Abu Ali and so, as Sigil, we approached them, telling them that we wanted to do a second Monuments of the Everyday project. But by the time we got our money together and our stuff together and figured out how we were going to do this, there had been already forty-two of these water wheels built in the entire landscape.

It was suggested by Abu Ali that we actually build a windmill instead. It’s a very similar technology to the waterwheel, but it allows us to build it further away from the agricultural canals. [...]

That was shown at the Marrakesh Art Biennale this February. And so this is now our third project which is called The Revolution is a Mirror. It’s a series of 5,000 magnets. We believe that the mirror operates in a very similar way to the windmill and the well, in the sense that it is a kind of architectural type that is easily recognizable but also has the ability to mean multiple things to multiple people at different times.

SaK: And can dissolve potentially into the infrastructure.

KM: We’ve made 5,000 of these. We are distributing around 3,000 here and another 2,000 in Beirut and New York and other places where we all live. There’s a hashtag online and we begin to collect new imagery of the revolution, namely your face, your street corner if you choose to put it on your street corner. These are all magnets.

The idea is very similar to the first two projects, where we begin with a type that dissolves into an infrastructure. Here, this is really the first phase of the project; this is the equivalent of the well or the windmill. Then we are going to build it into a larger narrative about spectacular viewing of Syrians: us looking at you, and you looking at us, and us looking at each other. [Hopefully], we’ll be able to put together an exhibition, because we think that in the past the infrastructure is provided for Syria and somehow the exhibition happened elsewhere, whether in Venice or Marrakesh. the mirror is both a reflection of who we are and also who we want to beBut in this particular case we’re keen on also giving people a chance to experience an exhibition and ideally, by complicating the images of Syria by including you brushing your teeth in that exhibition, so that perhaps you or someone you know would also feel moved to be engaged in what we’re doing.

We’re interested in how the mirror is both a reflection of who we are and also who we want to be, and so in a way we are as interested in someone who has this up next to her bed, and then wakes up the next morning and decides to do something for what’s happening in Syria, but also in people who just walk past it on the street and don’t pay it any mind. Because that obviously is part of the reality of people’s reactive relationship to Syria today, or to the Arab world in general. At the very, very, very, very least we hope that people who can’t read it will need to make an Arab friend to translate the text for them.

Can you go back a bit? I’m interested in how these projects acts as a sort of inverse to the way the Assad regime used monuments and architecture to bolster their symbolic presence. Your projects have a very pragmatic side—but I’m wondering how the symbolic narratives behind them are translated on the ground?

KM: I think any kind of political power that is formal across history [...] often expresses itself in space through the production of different forms of monuments. These are monuments that we’re all very, very familiar with and they’re often ignored in our daily life. However, as certain concentrations of political force, they are there.

I think in all of these projects we are trying to say something about how there’s [another] political force that actually exists elsewhere, mainly on the ground. It is able to challenge the traditional political forces that produce monuments. We also try to imagine what are the forms of these monuments that this force would produce. So far we have only managed to imagine three. One of them is a well that’s thrust into the ground and completely disappears into a network of pipes, a second is a windmill that produces power for a community project and the third is a mirror. It would be beautiful, potentially, to try to imagine what role this windmill would play, for example, in a post-revolution Syria when the good guys win. Or the well. It’s hard to say. But what I think for us is clear is that it operates as a particular node that exists within the everyday. What we are trying to do is to reign in some of this marvelous potential so that we live our lives more marvelouslyThe everyday experience of space and images is where we feel that there’s a certain potential for transformation, and that’s where we operate as a group. Yes, we have provided a well that gives 27,000 people water every day, but I think deep, deep down inside what we are interested in is the world in which we as architects who produce representations of space can actually transform not only representations but also space itself.

Sak: And even the moment when this transformation happens, when the well no longer is just a well but becomes something slightly more magical—what’s the word?

KM: Yeah, more magical, monumental. The word I like to use, in particular in relation to the mirrors, is marvelous. I think what Salim is trying to say is that we comprehend that the marvelous, like the monument, is very much part of the everyday—but slightly on the edge of it. What we are trying to do is to reign in some of this marvelous potential so that we live our lives more marvelously. That is why these projects, although they’re happening in Syria and, in this case around the world, are projects that are not about Syria but really about a very common, contemporary human condition, which I hope will move people in a particular way to rethink the water coming out of their tap or the telegraph as a marvelous infrastructure for communicating a dream.

For more articles from the 2016 Oslo Architecture Triennale, check out in-depth looks at some of the installations, our interview with the curators, and our review.

This October, Archinect's coverage focuses on the XXL of architecture — from planetary-scale computation to massive infrastructural projects. What are your XXL ideas? Submit to our open call by October 16, 2016!

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.