Los Angeles is defined by its freeways: everyone from Joan Didion to Ice Cube to "Saturday Night Live" has conceptualized the city through them. So why is such an integral part of the city’s urban fabric left largely to stagnate in the collective architectural imagination?

Aside from the occasional lane addition or designation, LA's freeways have remained relatively unchanged since they were first poured down decades ago. Generally speaking, infrastructure gets the most press when it fails: numerous U.S. cities have experienced embarrassing pipe breaches or life-threatening road and bridge collapses within the last few years. But to Michael Maltzan, infrastructure isn’t simply a colossal repair job, but rather offers the potential for dynamic urban reshaping and improvement.

Maltzan has spent the better part of his twenty-one years running his practice by investigating the potential of Los Angeles. His essays on public form versus public space explore the very particular urbanism of this city, which is to say a public realm that is singularly disarticulated. His recent proposal for the quarter-mile long Arroyo Seco bridge portion of the 134 freeway is a conversation starter, intended to help people reimagine how a seemingly banal piece of infrastructure could be transformed into a scalable, city-wide energy-saving (and generating) boon. It’s also a welcome way to reimagine how the U.S. generally approaches the topic of infrastructure itself. I spoke with Maltzan to get an update on the proposal.

I was fascinated by your proposal for a quarter mile infrastructural overlay of the 134 freeway, which muffles the freeway acoustically, generates electricity, grows plants, and catalytically converts noxious fumes. Has anything happened with that proposal?

There's been a few conversations with the city and interest in trying to move it forward with people who are connected or have some kind of relationship with other agencies. There hasn’t been any direct movement by CalTrans on it. I don’t expect it to happen right off the bat, but I’d like it to. My goal in doing this as a proposal is that I’ve been thinking about infrastructure for a long time with things like the 6th Street Bridge. I was thinking about a welcome way to reimagine how the U.S. generally approaches the topic of infrastructurethe 134 bridge in particular, which I go by all the time, and some of the issues associated with it. I had begun to think about and approach it, to turn a lot of the negative realities of the bridge, especially from an environmental standpoint, to turn the bridge into a more positive contributor to that area.

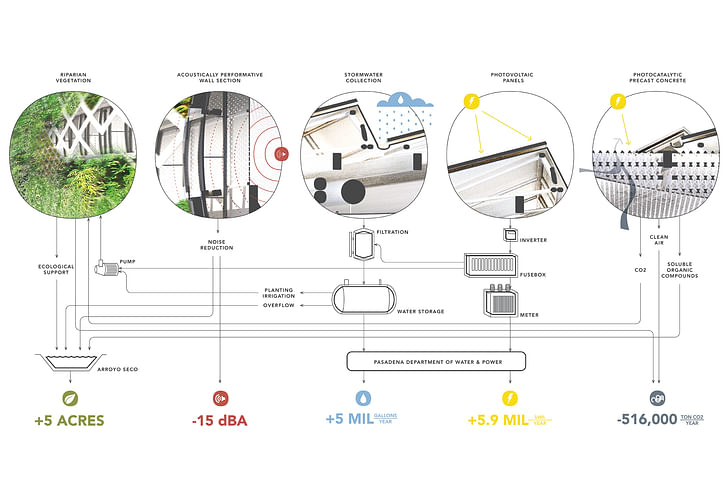

The goal was in the beginning to develop these ideas in a realistic way, with a lot of technical backup, in this case with ARUP, so that you could have a conversation about the role of infrastructure, just in general, not only specifically about this bridge. Now I’m focused on this bridge and seeing if we can’t truly make it happen. That’s a longer process.

Throughout your career, you’ve written about Los Angeles and the notion of public form versus public space. So many of your projects seem to address that in one form or another, very purposefully. It seems like you’re inadvertently (or advertently, I suppose) remaking the infrastructure of Los Angeles, which is cool.

[Laughs] I think it’s probably a little bit of both. It’s one of those things where it has—it’s a little bit of a chicken or egg situation, but I’ve been interested in this for a while, understanding that infrastructure broadly defined is absolutely one of the characteristic forms that has defined Los Angeles, but has been woefully underperforming for many many years, especially as the city has continued to evolve. I think that’s probably the case in many cities. But here with infrastructure, especially with the highways being such an iconic form that the city is identified with, it has more importance: to try to continue to evolve that in keeping with the way the city and the metropolis are evolving.

You rarely see a proposal for a freeway that isn’t just adding another lane, or something obvious and reductive. Your proposal seems very visionary in the sense of, "Let’s remake this huge component of Los Angeles into something beneficial." Have you figured out how to transform the entire city from an urban heat island into a lush forest?

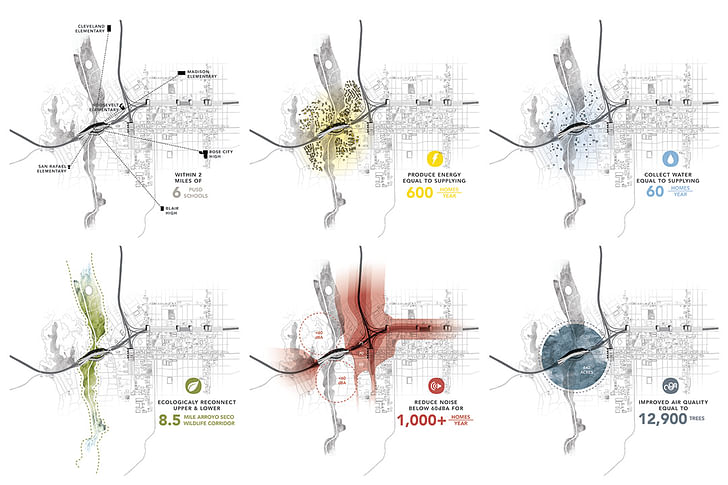

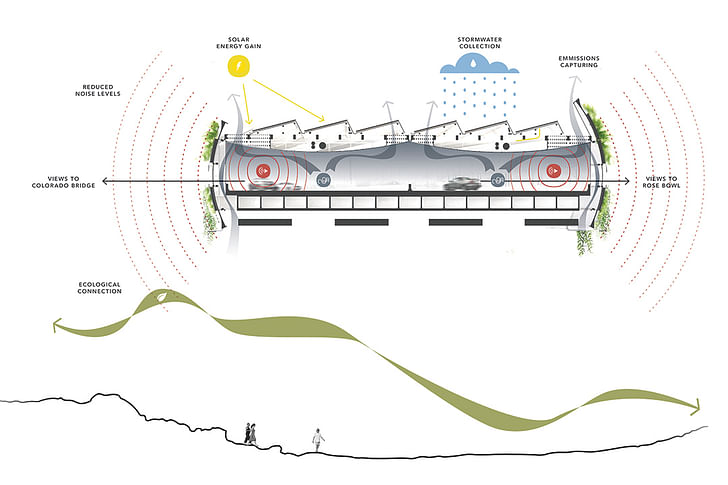

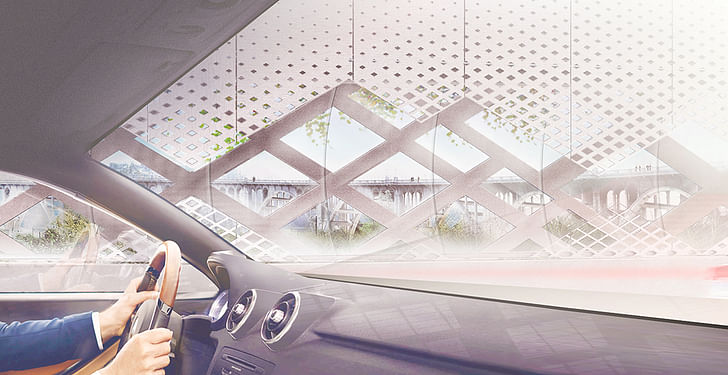

Well, the proposal for the 134 freeway, the reason I got extremely excited about the 134 is the piece of infrastructure that we would take on, it could carry so many different pieces of the larger puzzle—not only in how you change infrastructure’s role in the city but how you change all of the pieces of the environmental portfolio of benefit. In our proposal, we’re dealing with sounds, lessening the negative acoustic impacts that extend way beyond the freeway. We’re talking about miles of effect that any piece of the freeway has because of how far sound travels. We were looking at a collection of water because It’s a little like a menu: you can pick and choose which pieces you useyou have a significant amount of acreage that the top of the bridge or any piece of the highway creates. We were looking at solar and electricity generation for exactly the same reason: it’s very difficult to find large places to put solar farms in a dense urban environment. And one of the most underutilized pieces of land literally are the air rights over any of the highways, whether they’re elevated or sunken or a bridge. And then the greening of the sides of the bridge to work from an environmental standpoint, and just aesthetically for the visual environment of where that bridge goes through. And then finally the catalytic roof that we’re proposing, that takes the emissions from the cars and converts it, because of the way UV reacts to these titanium dioxide crates, and that acts as a catalytic converter.

All of these pieces don’t have to be in play for every mile of the highway all combined. It’s a little like a menu: you can pick and choose which pieces you use or you employ depending on what the different characteristics of the freeway are, and if it’s elevated or sunken down or at grade. I think that if you begin to take this and other ideas that could be added to the laundry list, and started to look at the highway network as a real positive and begin to retrofit pieces of it (especially when it goes through and affects different neighborhoods), I think it could be one of the largest transformative urban projects of any city, for any place on the planet.

CalTrans used to dream at that scale. The highways, when they were being built, coming out of post-World War II, were seen as one of the most progressive civic governmental projects that was being done any place on the planet. There were all these positive things that were meant to come from that. And I think it’s possible for an agency like CalTrans to reinvigorate the benefit of the highways. I think they’re going to be under more and more pressure to do that, especially as you start looking at the realities of autonomous cars and other means of transportation. That’s going to start to minimize or reduce traffic on the freeways, or at least the traffic footprint. I think it’s going to open up more and more space for the highways to perform in a very different way.

Investing in infrastructure is obviously something the nation should do more of. I hope we pay attention to nuanced projects like this.

I think there are very real issues. Most of the way we’re thinking about infrastructure investment over the last few years has been an argument about fixing the bridges that are falling apart and filling in potholes and maybe, as you said, adding a lane. All of these things are reasonable and necessary things to do, but at the same time, I believe that the agencies like I think it’s possible for an agency like CalTrans to reinvigorate the benefit of the highways.CalTrans, that control this work, should look at this in a more expansive way because it likely means that there are different funding streams that would be possible, would put them into stronger partnerships with the cities and neighborhoods that they run through. Frankly, they could use a better set of political relationships with any cities that they run through. These new projects could be done simultaneously with these renovation or retrofit or rehabilitation or fix-it jobs that we were talking about. When people talk about green economies and larger scale infrastructure across the U.S., this is one of those places where I think you tie these ideas to the necessary evolution of infrastructure: that it is to be mutually beneficial, on an altruistic and financial level, because you’d be able to connect pots of funding sources. That would be a really positive thing.

This piece is part of our editorial theme for October 2016, XXL.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.