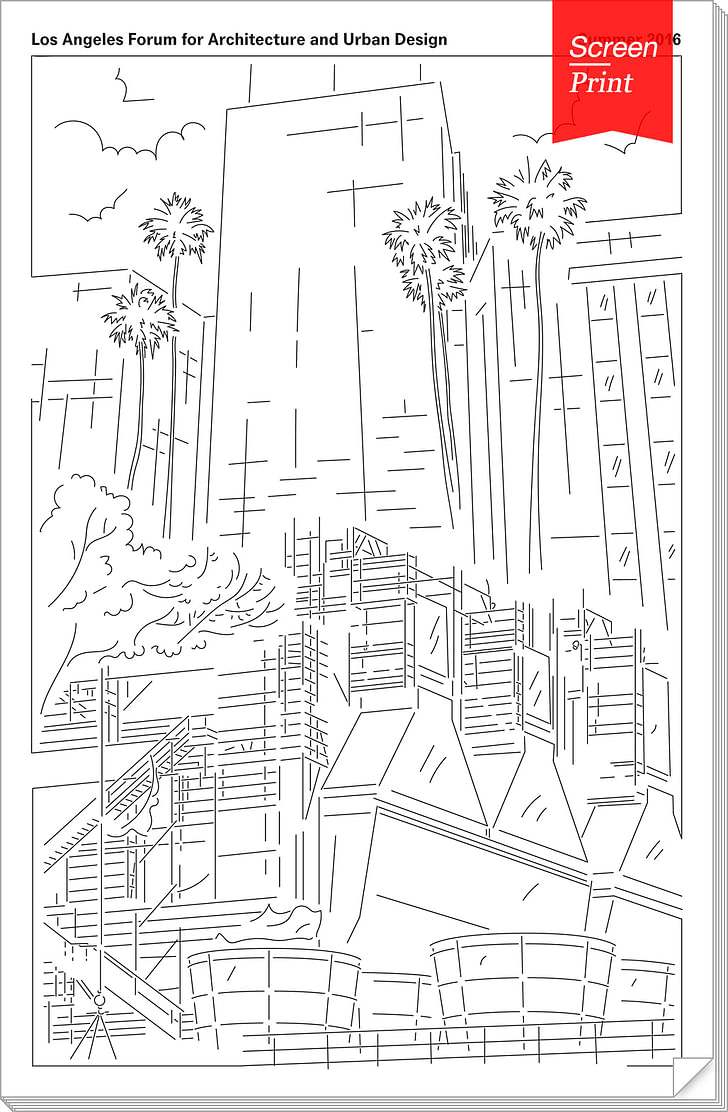

For locals and beyond, the Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design has a simple aim—highlight what makes L.A.'s architecture and urbanism discourse special, and what it can teach the rest of the world. Seasonally, LA Forum draws on its own board members and reaches into the community to publish a newsletter under a single theme or proposition.

For the nonprofit's Summer 2016 issue, board member Orhan Ayyüce curated thoughts from five contributors—some architectural, some not—in an attempt to “avoid the usual premeditated and often templated conversations about architecture and urban design.”

Alongside pieces from architect Victor Jones, artist William Leavitt, architect Ilaria Mazzoleni, and urban geographer Rob Sullivan, Ayyüce conducted an interview with actor Bob Wisdom, featured in its entirety as our Screen/Print. Wisdom grew up in Washington, D.C., and spent time in Baltimore before moving to New York for university. He now lives in Los Angeles, and in nearly thirty years of acting, is perhaps best known for his role as Howard “Bunny” Colvin in HBO’s The Wire.

Orhan Ayyüce sat down with Wisdom, to speak about the show’s depiction of race and crime in American cities, as well as the actor’s own observations on east vs. west coast urbanisms.

City Takes: Orhan Ayyüce interviews Bob Wisdom

The TV series The Wire has a big following amongst architects because it focuses on urban issues. I was wondering if you guys had any kind of discussion about this on the set?

That’s interesting. I don’t know if there were conversations between myself and the other actors. The producers, Ed Burns and George Pelecanos had a vision in their own work as artists. Pelecanos writes about the urban condition in Washington D.C., with very detailed and specific backdrops in his story. And then there was Ed Burns who knew the Baltimore schools, knew the Baltimore police force, and knew these issues. So, he was one of the architects who shaped the story.

We would have reflective conversations. But amongst the cast, all of us knew these conditions in our blood. We never spoke of them specifically, but myself with Frankie Faison, who played the Police Commissioner, or with Andre Royo, who played Bubbles, or the other characters, we go into a scene with the comfort on those locations because it was something that we just knew. We were turned on differently.

And we would call them our homes. We never perceived them growing up as projects and ghettos.An interesting case was the woman who played Snoop, Felicia Pearson, who came in the fourth year. She came into the story just through a chance meeting with Michael K. Williams who played Omar, and he said I’m going to bring you to the show and introduce you. She had never really done any real acting before, but she knew that world so deeply and was a part of it, then, bang! He dropped her in and she never missed a beat. The acting was not a challenge at all because she could actually be that part. I remember my first day going in as Bunny, and I sat in the trailer with two of the executive producers and I didn’t know where the story was going, but they took the time to talk me through this first episode. And then, we went out on location. I walked into this housing project, and the story line was that a young boy was accidentally shot in the line of fire and killed; that triggered a lot of frustrations for Bunny Colvin. I remember walking in there, and it flipped me back to when I was growing up, and my cousins lived in these kinds of housing projects that we have in Washington, then in Baltimore, where there were just these split-level, four-unit buildings scattered throughout the complex. And we would call them our homes. We never perceived them growing up as projects and ghettos. I didn’t perceive projects on the scale that the way that they’re spoken about in American culture until I got to New York in college. And then I saw these huge high-rises, you know, 40-story, 50-story monoliths.

How does The Wire deal with the political handling of the projects?

David Simon (the head writer, creator of The Wire) clearly describes the inherent ironies, the conflicts, the contradictions that certain policies have, and they get manipulated by those in power, and that’s how poor people get destroyed by mistakes. And that’s what kept us all there. Now, in terms of solution, I don’t think anybody’s made a show about solutions.

Wasn’t the power of the show that fact that it didn’t offer solutions?

Yes. And that’s what made that narrative so powerful, because it was so clinically defined—what the nature of an American city was. So you could take, Baltimore as Camden, as We are in the worst, most cynical understanding of politics we’ve ever had.Patterson, as Pittsburgh, as a bunch of American cities, the East Coast cities, particularly, where the middle class had been moved out or tried to move out, black folks took over the center city and there was decline. We saw that up and down the East Coast. The show had value in the 2000’s, describing to a larger group of Americans who were born after the 80’s to catch up on some of that history, to try to get the sense. But as we move into the middle of the second decade of the 2000’s, I think at some point we have to figure out, what are possible solutions? And, that’s really daring. I don’t know of anybody that can take that on, but I’d like to think that’s the kind of show, as an actor, I’d like to take part in. We jump from shows like The Wire to science fiction shows, but there’s nothing reality-based that looks at the positive sides of American politics and the political decisions that shape our cities. We are in the worst, most cynical understanding of politics we’ve ever had.

We have no faith in the political system. Hence, twenty-two percent of people vote in national elections, and less in local elections—twelve percent in some places. That’s what’s happening. Those are people who will fight to the teeth; they own the store down the street, the flower shop in their neighborhood. They’ll turn out for that, or the dog park. But in terms of how the wheels get turned, if they can go in and have immediate influence and pay their I remember driving through Leimert Park. I was like, this is ghetto?politicians directly in the pocket and get their voice heard, that’s as close as they get to activism. So activism is becoming a neutered choice, because protesting from the outside doesn’t have the impact that it once did. It’s an insider’s game.

I had a friend visiting from the Netherlands, and I took him to South Central L.A. He was a documentary filmmaker and he couldn’t believe it. He said this looks like South Africa. Coming from the East Coast, how do you see the neighborhoods in L.A.?

See, for me, when I came from the East Coast to California, and I remember driving through Leimert Park. I was like, this is ghetto? I mean, you had houses, lawns, manicured sidewalks and the whole thing. I was like, this wasn’t the ghetto where I grew up. But still, I met people who grew up in L.A. who had no idea of what was south of the 10 Freeway.

They still don’t.

That’s the story right there. The investment is passed on from generation to generation. We invest in this area and your life is invested here. You have no interest in the rest—that is somebody else’s place. And so we have all of these neighborhoods. To this day, I have a very, very clear idea that I don’t go to Orange County. That place has a certain kind of meaning. And I don’t even know if I can articulate outside of, you know, white, blonde.... It’s very mainstream, middle class, consumer-oriented, but if there were a massive activist protest that grew out of Orange County, it would shock me today. Those aren’t the people you expect to, in any way....this gentrified thing is now the perfect little, nondescript kind of ghetto.

Must be, they don’t have anything to protest.

Growing up, you go into an old neighborhood and the food was rich and full. Then you start having the new population come in, and they don’t like it cooked with so much fat. And so there’s a little less put in, and all of that and there’s nothing left. That’s the American invasion.

And so this is what’s really happening with gentrifying the neighborhoods. Looking for culture and beauty in the city, and as soon as it’s found, it is turned into nonfat.

Yeah, pre-packaged. They also want urban safety as the number one value. So you see the mothers here in their carriages with their babies, they don’t want anything that will threaten their walks during the day; they go shopping and they have no ambition beyond that, you know. So this gentrified thing is now the perfect little, nondescript kind of ghetto.

You travel to different places, especially Morocco—how do you view the cities there? How do they function?

Casablanca has all of the trappings. You stand up on a rooftop in Casablanca and you look over the city, just televisions everywhere. Satellites. You look up at the sky and you see the electricity wires. But inside...inside, you still have a life that’s shaped by the Koran, that’s shaped by always taking care of a neighborhood. Even though the people in Casablanca pay modern prices for their neighborhoods, they still have the place where they go buy their bread—the one that bakes bread for that community, and the corner shop where they get milk, and the same way of running other things. Then you go to Fez, to Marrakech, and to all the smaller towns, and you see cities that are run intuitively by this same kind of people with the same practices that generations before established. And that living arrangement is shared. You take care of the person down the street the same way you take care of your we have none of that shared intuition on how to service each other.family. And that person takes care of you and looks out for you. All of these things are part of urban living. And contrast to over here, we have none of that shared intuition on how to service each other. Growing up, there was a white woman who lived across the street from us. She would have me run down to the corner store, almost every day, get her newspaper, the Washington Star, and a bottle of milk, and I’d come back and she’d give me a nickel. That was Miss Colder. It’s a neighborhood family.

And it still exists in black neighborhoods.

It still exists. But because of gentrification, this family is broken up and some of them live here, some live there; I moved from the East Coast to the West Coast, and now I’m like, living in this box, you know. I talk to everybody in my building. When I first moved there, I knew everybody, and we all knew each other. And some evenings when it got hot, I used to leave my door open, and people would come out the elevator, and they would just see my door open, and shout out, hey, Bob! You know, it was just shared space. And I watched as some of the older residents moved out, I’ve been there now 25 years, so I’ve seen them all come and go. Different and younger people come in now, and it’s like you stand in the elevator with them and some of them don’t speak, you know. And I start a conversation, “How are you doing? Good morning, good morning.” And they feel confronted by that kind of thing, I see the culture clash. I think that’s what I want to fight for, to keep it humane—in the way that we live together, keep the meaning of social life alive. Just to acknowledge each other, say good morning. The blocks in the brain that you develop to keep you from saying good morning to your neighbor, it’s a huge thing.

Like you said earlier, these people, the new people, they don’t have any cultural incentive in any of this. To them, it’s a place they rent. They pay their thing and that’s that. That’s as far as they’re going to know people. And they think whatever happens there, it has no bearing on their life.

And the idea of a rental is a stepping-stone to something else. They’re not going to live there 25 years. So then they buy something, and then once they do that, then the next That discriminatory map exists.thing they do is they have a kid or start a family, and they’ve already bought into a subscription. And that’s where they get you in the chain. You’re in the chain. You’re going to move to this, to this, to this. And more and more safety. More and more homogenous living.

A few years ago there was a Beverly Hills, Chamber of Commerce meeting. They didn’t want a Metro station there. They didn’t want a Metro station.

And that divisive map still exists. That discriminatory map exists. And, is institutionalized under a veil. I would drive around Beverly Hills at night, there was more of a chance of being stopped driving through, when I had my old Volvo. Now I have a hybrid—it’s a different kind of profile. But once upon a time, I would get stopped going through there. So I would drive down to Venice and come into West side through Venice. And these are the kind of things that... and it’s about the map, you know. I don’t think a lot of people realize the scale of this problem. It’s self-perpetuating. Once upon a time, you didn’t see these communities, or the accessibility of these other communities. It didn’t matter to you. Now, you look on the internet and you see this other way of living, things people have.

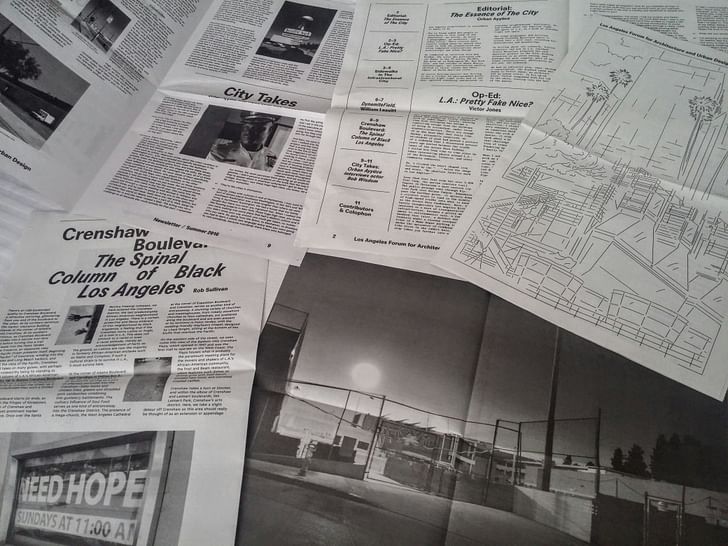

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured LA Forum Newsletter – Summer 2016.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.