20 kilometer long traffic jams, eleven dead construction workers, and one slain jaguar: the lead-up to the 2016 Rio Olympics has not been problem-free. Zika, pollution and political turmoil came alongside construction delays and problematic venues, with competitors refusing to move into the athletes' village until the wiring was fixed. And yet, aren't these types of problems just par for the course when it comes to the Olympics?

From an architectural standpoint, the Olympic Games are often a terror. Massive construction projects that are designed years in advance often exceed contemporary construction budgets, potentially provoking drastic last minute cuts and reconfigurations to fit the initial bid. Many residents in the pathway of new construction projects find themselves in the shadow of eminent domain; their property is either seized or made uninhabitable by construction crews. And then, of course, there’s Santiago Calatrava. Need more be said? Well, maybe a little more. In anticipation of Rio's Olympic Games, which begin today, here are some of the most notable architectural incidents in recent Olympic history: for better and for worse.

RUDEST EMINENT DOMAIN: Sochi 2014

According to a report in Foreign Policy, Russian residents whose homes were located near construction sites for the 2014 Winter Games were told to quit their bitching after they found their basements flooded with dirty water, their homes full of mold, and their courtyards suffused with freshly dredged mud, thanks to Olympic construction crews. Putin’s government felt the eminent domain of the games outstripped people’s domestic rights: in fact, Sochi City Hall sued people who refused to demolish structures that were in the way of the construction, including kitchens and outhouses.

MOST NAIL-BITING: Santiago Calatrava’s stadium cover, Athens 2004

Officially selected in 2001, Santiago Calatrava began design work on creating a cover for the Olympic Stadium, a timeframe that was already fairly tight as the project had to be built and ready by June of 2004, to allow for light rigging at the beginning of the games in August. the execution was crazed.Thoughtful and precise, Calatrava created a design that he described thusly: “the plan is classical, the elevations are Byzantine, and the spirit is Mediterranean."

However, the execution was crazed. A 36-page report from the Harvard GSD details the structural weight-bearing efficiency set-backs, redesigns, and political inter-agency complexities of Calatrava’s roof, which at one point looked like it wouldn’t be built at all. But by June 5, 2004, with absolutely no time left to spare, the construction reached a finalized stage.

BEST USE OF DISSIDENT ARTIST: Bird’s Nest stadium, Beijing 2008

Although Herzog & de Meuron had to redesign their initial plans for the stadium that would come to be known as the “Bird’s Nest”, due to unanticipated construction costs and structural weight-bearing concerns (kind of a theme for Olympic Stadium design, it seems), they wound up creating, with the artistic input of Ai Weiwei, one of the most iconic Olympic structures in the world.

The seemingly random swirls and curves of the 110,000 tons of exterior steel arches of the Beijing National Stadium form two almost perfectly symmetrical halves. Also, the stadium is somewhat environmentally conscious: a nearby rainwater collection point purifies water to be used in and around the stadium. Unfortunately, post-Olympics the stadium hasn’t been booked very frequently for massive events: a retractable roof was removed early on in the construction process, leaving the field perpetually open to the sky and therefore vulnerable to fungus from heavy rain.

MOST ADVANTAGEOUS EMINENT DOMAIN: London 2012

Unlike the moldy lives of their Russian counterparts in Sochi, some of those in the pathway of London’s 2012 Olympic Games turned eminent domain to their advantage. Lance Forman, the owner of H. Forman & Son, a salmon smokery situated on the 500 acres of land in London’s East End earmarked for the Olympics, was not keen to sell his factory at the terms of the compulsory service agreement set by the government. As Forman noted in Sports Illustrated, "The greatest manufacturing area in all of London was to be essentially wiped out Our strategy was to make an absolute nuisance of ourselves to get fair compensation.for three weeks of sport. Our strategy was to make an absolute nuisance of ourselves to get fair compensation." By refusing to cave in, Forman managed to get his smokery bought out for an undisclosed sum, allowing him to a build a brand-new and improved version about one hundred yards away.

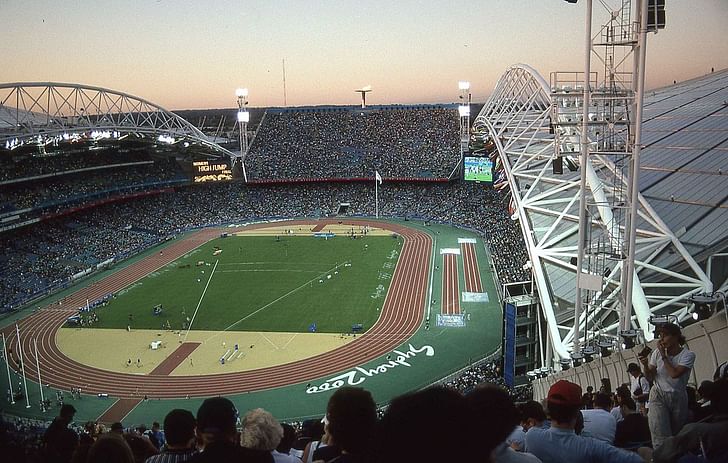

LARGEST OLYMPIC STADIUM: ANZ Stadium, Sydney 2000

The ANZ stadium is the largest Olympic stadium built, with an official capacity of 110,000 spectators (although after the Olympics, the stadium’s capacity was shrunk to seat only 83,500 spectators when an oval-field orientation was introduced). Correspondingly, it holds two Olympic records: the largest crowd for any athletic event, when 112,524 spectators showed up to watch an Australian win the gold in the 400 meter track and field race, and the highest attendance ever in Olympic history for the closing ceremony with 114,714 spectators. Designed by Bligh Lobb Sports Architecture (a Populous joint venture), the ANZ Stadium never had any of the complicated steel arches that frustrated Calatrava and Herzog & de Meuron.

SHADIEST CONSTRUCTION PROCESS: Utah Olympic Oval, Salt Lake City, 2002

Accused of bribing their way into the hearts of the International Olympics Committee, the Salt Lake Organizing Committee had been hoping to host the Games for years. Before they finally won the bid in 1995 (and survived the bribery scandal in 1998, which led to the expulsion of some IOC members and an investigation by the Department of Justice), Salt Accused of bribing their way into the hearts of the International Olympics Committee, the Salt Lake Organizing Committee had been hoping to host the Olympics for years.Lake City had started working on an Olympic ice-skating rink in 1992. What would eventually be called the Utah Olympic Oval was initially built as a roofless skating rink, but the first concrete pour couldn’t be completed on schedule because it was too cold outside.

Once the official Olympic nod was given, the city reached out to local architects Gilles Stransky Brems Smith to design a roof for the completed rink at $27 million. Unfortunately, the construction process was fraught: in addition to a section of the roof collapsing mid-way, the freeze tubes in the newly poured concrete floor had moved out of alignment, necessitating that it be torn up and poured again if the ice was to freeze evenly. The total cost ended up at $30 million.

This feature is part of Games, our special editorial theme for August 2016. You can find more related editorial here, and submit to our open call by August 21.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.