Sometime in the last few years, your couch became a rentable asset; your bedroom, a factory; your taste, a commodity; your doorstep, the final destination for a package that has more freedom of movement than most of the world’s population. What, then, does it mean to be at home today?

This is the question proposed by After Belonging Agency, the curators of the 2016 Oslo Architecture Triennale. Entitled After Belonging: A Triennale In Residence, On Residence, and the Ways We Stay In Transit, the Triennale probes how architects and designers can respond to new socioeconomic, political, and technological conditions changing the domestic landscape and how we inhabit it. “Global circulation of people, information, and goods has destabilized what we understand by residence, questioning spatial permanence, property, and identity—a crisis of belonging,” they write.Global circulation of people, information, and goods has destabilized what we understand by residence

Composed of five Spaniards—Lluís Alexandre Casanovas Blanco, Ignacio González Galán, Carlos Mínguez Carrasco, Alejandra Navarrete Llopis, and Marina Otero Verzier—the After Belonging Agency was formed specifically for the Triennale. Unlike most architecture exhibitions that favor a strictly representational model, After Belonging includes commissioned reports and strategic, long-term interventions chosen from an open call, alongside a more traditional exhibition (that also seeks to break the exhibitionary mold of models on plinths and hung-up renderings, it should be noted).

I talked with two of the curators, Marina Otero Verzier and Ignacio González Galán, to hear more about the context they’re analyzing and the methods they’re employing.

What's your background and how did you come together to do the Oslo Architecture Triennale?

We were all friends and colleagues living in New York. Some of us studied together at ETSA Madrid, and later on at Columbia University GSAPP. We shared interests, and had previously collaborated. But basically, the Agency—as a formal work platform including the five of us—came together for this particular project. transformations are redefining what we conventionally understand by belongingIt was created around common interests that coalesced under the topic we proposed for the Oslo Architecture Triennale 2016: the role of architecture within the transformed condition of belonging, or an architectural scenario After Belonging.

When you came together for this project, were you responding to an open call?

There was an open call for curators, and we took the occasion to consolidate previous conversations. More than seventy teams presented proposals—this was in the fall of 2014—and four were invited to interview in Oslo. There was an international jury with curators, practitioners, and thinkers. We were finally selected for the project in December 2014.

To get right into the nitty-gritty of the project, you write on the website "being at home entails different definitions nowadays" and that you examine two primary questions. To begin with the first, ‘Where do we belong?’: what do you see as the major transformations occurring in the landscape of domesticity and belonging, more broadly? In other words, what is the context of the Triennale?

What we are trying to examine is how we establish relationships in communities and alongside territories considering the contemporary conditions of circulation of population, things, information, images, and knowledge. We believe that these transformations are redefining what we conventionally understand by belonging. In a certain way, belonging and architecture have been many times associated with ideas of permanence, enclosure, and stability. We are trying to see how those concepts are being redefined.

In our curatorial proposal, the notion of residence, or the house, is taken both literally as an object—within this new condition, our houses have undoubtedly changed—but also as a concept that allows us to rethink what it means "to be at home", a condition that is normally associated with ideas of belonging, both in terms of familiarity and stability.We’re looking at new forms of connecting and relating to the objects that we own, share, and exchange

The second question that you propose is to look at how we manage our belongings and changing modes of ownership. Can you elaborate on this?

We’re looking at new forms of connecting and relating to the objects that we own, share, and exchange, and the systems of logistics and infrastructures that allow for these new relationships. In this sense, we can think about furnishing, decoration, equipment for architecture, and the different ways of expressing identity that these convey.

For example, furnishing projects could be a lens through which to understand how architectural systems of property, ownership, and legacy are being recodified by the so-called “sharing economies”. We also look at strategies of reuse, at the architectures of storages facilities, and at the changing networks of commerce and logistics, like the ones that are facilitated by companies like Amazon.

I know that you had a big open call for the In Residence project, were these two questions the guiding framework with which you looked at projects?

Maybe it’s better to define the relationship between In Residence and On Residence first and then explain the call. The idea was that this was a Triennale dedicated to residence, so it was, in a certain way, a Triennale On Residence. And that is one of the main platforms of the Triennale, an exhibition at the Center for Design and Architecture (DoGA) with contributions reflecting on this redefinition of residence.

But we thought this was not enough, and that the Triennale could also be a space to think how architectural practice could be redefined to address these changing conditions. We thought that we could do a Triennale “in residence,” like the in residence programs in which you are called to develop a long project, on site, throughout some months. So that's how we defined the Triennale In Residence, for which we selected a number of sites around the world that were offered through this call of intervention strategies. The goal was to identify modes of practice that could be developed for these sites as a way of intervening in them.

The In Residence platform includes not only the intervention strategies, but also reports that we have commissioned about those sites. In sum, it is a case-study approach, in which ten sites are defined through the reports, and some of them will have interventionist strategies operating upon them.it is a case-study approach, in which ten sites are defined through the reports, and some of them will have interventionist strategies operating upon them

Could you walk me through a few of them?

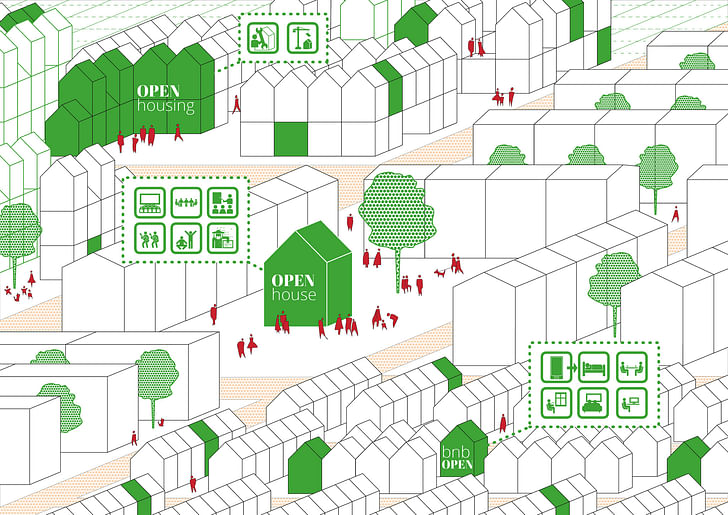

Open Transformation, for instance, explores alternative ways of meeting asylum-seekers' needs through notions of hospitality trying to overcome the distinction between "us" and "them," which permeates many related discourses. The selected team is developing an architectural intervention operating at three different scales: bnbOPEN, an application that would allow asylum seekers to find and share ordinary housing as an alternative or supplement to reception centers; OPENouse, a place for gathering in the city to share knowledge and experiences between recently-arrived individuals and local communities in Oslo; and finally OPENHousing, an ongoing research project that aims to re-imagine housing policies in Norway to intervene in larger processes of migration. OPENHousing seeks to open up a debate on how housing could be rethought as an alternative to the real estate market forces currently shaping all the options for accommodation.

These three interventions take the Torshov transit center [or transittmottak] in Oslo as a point of departure but, as you can see, materialize differently throughout the city—from a digital application to a public conversation about current housing policies and regulations.

This project is being developed by a group of architects and sociologists for this particular case study that we proposed for the call. For that same site, the transit center in Torshov, there is another group of architects developing a city guide for and by asylum seekers, which hopes to create new relationships between the recently arrived and the local communities, which are many times disengaged from each other and, in a certain way, advocates for the right to the city for all inhabitants despite their origin and legal status.

Another, very different, case study is an Airbnb apartment in Copenhagen, and for that a team of architects, planners, and graphic designers have gathered together to create a strategy of exacerbation: they are developing a new app that offers the possibility of renting not only your apartment for short stays, but also objects and situations. It's a way of addressing the increasing compartmentalization, and monetization, of all our goods and activities.

Others cases and interventions include, for example, the introduction of certain designed objects in the Oslo airport, Gardermoen, with the aim of producing dissident activities in the otherwise normalized behaviour of passengers, as well as the development of a platform for political gathering for a new form of eco-political governance in the Arctic region, between Norway and Russia.A key aspect of our approach is that we are not concerned with problem solving.

These are very diverse projects and so are the profiles of the groups, with researchers and practitioners coming from all over the world and developing different kinds of expertise.

And, in a way, we could say that through these interventionist strategies, the Triennale has already started even before its official opening. These projects will be shown in the National Museum – Architecture in Oslo, but as ongoing processes, the teams will be working on them until the end of the Triennale and even after. For example, in the case of Open Transformation, the team has expressed interest in continuing to develop the project in the years to come. They are taking the opportunity offered by After Belonging as a starting point for a project that will have a larger life. And that, for us, is one of the aims of this Triennale, that the conversations and collaborations initiated as part of this project will have a lasting legacy and impact.

There are many different roles for the architect being positioned, it seems, from exacerbating conditions to creating conflict. Is there a role you're positioning for the architect or designer in this "after belonging" context?

We think that this is a fundamental question. A key aspect of our approach is that we are not concerned with problem solving. To embrace a problem-solving strategy in such complex contexts as the ones we are trying to approach seems to us a little bit naive and, in many occasions, problematic. What we are actually trying to do is to test work protocols through which architects can establish long forms of engagement with these complex realities, bringing together the different agents, institutions, and technologies that are participating in the construction of the "architectures". And the role that the architect can play in articulating those is very diverse, but the problem solving attitude of the architect as a super-powered individual is one that we refuse to embrace.

That is why we thought that it was interesting to try these strategies through a year-long process, through a work protocol that could be tested throughout time, rather than a very rapid response.The exhibition brings together diverse modes of practices, forms of representation and display

Could you tell me a bit more about the On Residence component?

On Residence is both an an exhibition that will happen at the Center for Design and Architecture (DOGA) in Oslo, and a publication with essays by guest contributors. It includes different propositions, narratives and theoretical arguments connected to five main topics that we have titled Technologies of a Life in Transit, Markets and Territories of the Global Home, Sheltering Temporariness, Furnishing After Belonging, and Borders Elsewhere. The contributions from the different participants are aggregated around these five topics, but are not necessarily looking at—or responding to—just one of them; they are all somehow fluidly interconnected.

The exhibition brings together diverse modes of practices, forms of representation and display that, we believe, allow rethinking and intervening in these changing realities that the Triennale addresses. So, in the same way that In Residence proposes new forms of architectural practice, On Residence reflects on what are the forms of representation, the documents and modes of expertise in which these can be manifested, including video installations, data analysis and visualization, and many other techniques.

Do you find that Oslo, and Scandinavia more generally, is a particularly relevant site for these questions?

We think that Oslo is one possible case study and, of course, it shapes, particularly, some of the lenses through which we are looking at the realities “after belonging”. We could have looked—and in fact we are looking at the “after belonging” condition in other sites—and that is why only some of the ten selected sites are in the city of Oslo. But definitely the fact that we are working in Oslo informs some of emphases of the project. For example, the current crisis of the European Union, in a certain way, informs our approach. We are also, inevitably, addressing what has come to be called the refugee crisis in Europe, which is a much longer and wider phenomenon, but that has acquired now a particular relevance in European countries. All these questions are definitely important for our project.

Oslo's population has a very large migrant component. However, the configuration of the city is one that excludes, in many ways, the understanding of its diversity. the configuration of the city is one that excludes, in many ways, the understanding of its diversityThus, for us it was very important to put on the table a topic that could allow the Norwegian cities to approach a reality that is not foreign to them.

The project is definitely informed by local conversations and realities, but we are trying to address a much wider condition. Something that has been very useful for us is that the Triennale is an organization that has a board configured by different local organizations, including the Oslo School of Architecture AHO, the National Museum — Architecture, the Association of Norwegian Architects, and the Oslo Business Region. Having conversations with all these institutions and working through the preparation of the curatorial proposal together with them has definitely helped us inform our project in a way that might be both relevant for a global audience and to the city of Oslo and the Norwegian audience.

Is there anything else in particular you want potential visitors to know in advance of the Triennale?

Something that we like to explain, because it's a little confusing from our title, is that this idea of "after belonging" shouldn't be confused with a "post-belonging". We are not looking at a condition where belonging does not exist—where we all move, and we are cosmopolitan nomads going from Airbnb to Airbnb. We are also not nostalgic for all forms of belonging. We are not nostalgic for the time in which we were happy in our local communities and relied on traditional forms of familiarity.

This after belonging is more a pursuit for new modes to consolidate communities, modes of relationship with the territory, and processes for managing objects. So we are after belonging—that is, after new forms of belonging—and we hope that architecture can participate in the construction of those new forms. That is what the project aims for. And it does so sometimes with a critical perspective, looking at the way certain instruments ideologically contribute to the construction of nationalisms or religious fanaticism. But, in some other instances, it also does it in a positive way, looking for these new constructions that are inherent to our contemporary world.

There are many different ways in which our relations to places, collectivities and objects have changedThe topic of the Triennale and the discussions it triggers are also connected to other contemporary questions and challenges, such as what has come to be called the refugee crisis, the new border fences that have been recently erected by European countries, or the Brexit referendum. And, of course, to other situations happening beyond the European continent. For instance, the rejection by India of over 50% of visa applications from Pakistan since January 2016. So there is a sense that a reorganizing of borders is taking place, as well as new economic-political relations in which architecture—understood not only as a construction, but also as larger territorial configurations and relations—has a role. To us, what would be interesting is that, together with the participants and the audience, we are able to rethink what are the new conditions of belonging that are being manifested in all these different forms.

And among these other forms of belonging, the Triennale also addresses how technologies might allow for forms of sovereignty that are not necessarily connected to the nation-state; and how ideas and imaginaries of success circulate in social media, having an impact in global migration.

There are many different ways in which our relations to places, collectivities and objects have changed. And we are presenting these as questions to the discipline of architecture, but also to the general public, as these different conditions and events are affecting the everyday life of millions of people around the world. We are asking how architecture is involved, and how architects could take part and participate in these transformations of residence and belonging.

This interview was conducted by Nicholas Korody, via voice call, with two members of the curatorial team of the Oslo Architecture Triennale 2016, Ignacio G. Galán and Marina Otero Verzier, and later transcribed and edited by Nicholas Korody with input by the curatorial team (Lluís Alexandre Casanovas Blanco, Ignacio G. Galán, Carlos Mínguez Carrasco, Alejandra Navarrete Llopis, Marina Otero Verzier).

This interview falls under Archinect's July theme, Domesticity. What will the home of the future look like? Submit your case study 2.0 projects to our open call by Sunday, July 24 at 11:59 pm (PST). For more domesticity-related features, head over here.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.