In the 21st century, the couch is so ubiquitous as to be virtually invisible. We find them in commercial waiting rooms, in private homes, as infested harbingers of urban decay on street corners. They populate television talk shows and form a shorthand for psychiatric evaluation. But how has this piece of furniture, which has only been around for about 330 years, become the seat of our culture?

From the first couches in the court of Louis XIV to the modern designer masterpieces to our contemporary, IKEA-saturated, “smart-couch” era, each iteration of the couch reflects our evolving relationship to the boundary between common areas and private realms.

The couch as we know it did not exist before 1680, when French King Louis XIV burned out on having to pack up and move all of his furniture each time he relocated to a different palace. As Joan deJean details in her decorative, non-mobile furniture, which transmuted the rich decorative aspect of tapestries into the first forms of furniture upholstery.book The Age of Comfort: When Paris Discovered Casual – and the Modern Home Began, in the 16th and 17th centuries it was customary for royalty to break down all of their furniture, including wall-art such as tapestries, and move them to their next unfurnished location. This practice largely discouraged the making of decorative furniture, favoring instead hard, linear benches and tables. In 1662 Louis XIV appointed tapestry-weavers The Gobelins to create the royal meubles (a term deriving from the latin word for “mobile”) or furniture. Under The Gobelins, a roster of architects, furniture-makers, and other craftspeople came together to create decorative, non-mobile furniture, which transmuted the rich decorative aspect of tapestries into the first forms of furniture upholstery. The canape, or sofa (in its straight, low-backed, often feather-stuffed upholstered form) was born. Within only a few years, the ability to carve backrests and armrests created much a higher-backed, more ornate version. Curvature followed quickly.

Unsurprisingly, the couch thrived because of an increasing trend toward privacy in architectural design. In the Sun King’s time, people didn’t have private living rooms so much as public common areas. This changed as grand apartments were divided up into small, cozy living spaces, such as salons and the King’s ‘Cabinets du Roi,’ spaces which were described unflatteringly as nids de rats or “rats’ nests” by the Marquis D’Argenson. As Joan deJean writes in her book, “Furniture went modern in close partnership with architecture. New pieces and styles of furniture were originally used in newly invented rooms… Between 1675 and 1740, people went from living with only a few stiff chairs with no padding to being literally surrounded by a truly dizzying array of well-stuffed and padded, curvy, and ‘orthopedically’ proportioned seats: from armchairs to sofas to daybeds and chaise lounges.” With comfortable furniture came an entirely new concept: that of relaxation.

The sofa wasn’t something you could just sink into and luxuriate in. Sprawling was not decorous in the 18th century.This was evident especially in France, where many of the new pieces of furniture had first emerged. Instead of spending life moving from one unyielding surface to another, the French nobility now had the luxury of actually enjoying being seated. In the 1760s, the sofas reflected this in their design: the ottoman, with its rounded frame and back, required upholstery on both sides. Averaging 6.5 feet, but sometimes extending up to 10, the plushness of the ottomans was both comfortable to sit on and very lucrative for the upholsterers themselves, who were frequently employed to re-cover the sofas in different fabrics. But what of the notion of the retreat from the common realm into the private? This is perhaps best demonstrated by the ottoman’s close sibling-in-design and upholsterer’s cash-cow, the confidante, which according to deJean took its name from the notion that “at each end, someone could snuggle up to one of the cheeks and trade secrets with a confidante seated on one of the end seats.” A sofa with “wings,” or armchair-like appendages, the confidante wasn’t a direct replacement for the long, stiff benches of the old common rooms; it invited a certain feeling of intimacy, a withdrawal from the socially common into an exclusive, private realm.

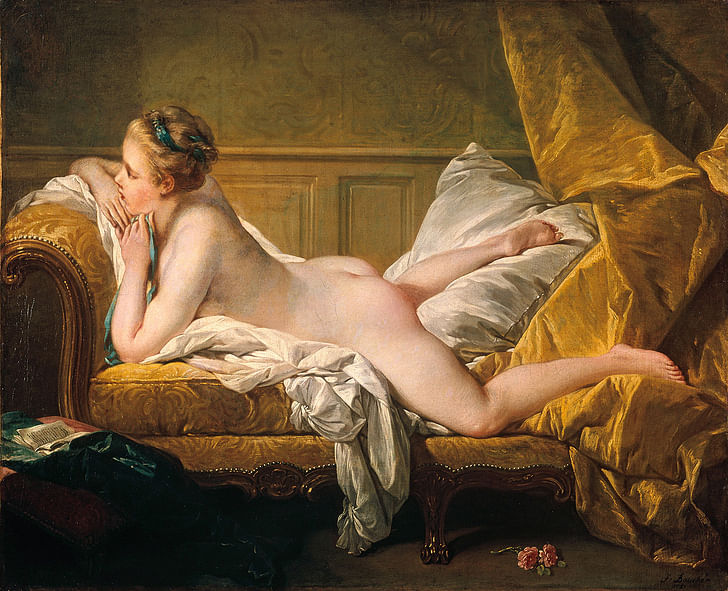

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the couch continued to reflect this trend towards privacy, taking on additional psychological connotations. Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Art History at Skidmore College Dr. Mimi Hellman approaches the couch as a social actor. “Given the clothes that people were wearing, and the very controlled way in which people were meant to the couch was a newfound nexus of erotic energycomport themselves in the 18th century, I’m interested in the way that a piece of upholstered furniture might actually make you manage your body very carefully,” she explained to me over the phone. “The sofa wasn’t something you could just sink into and luxuriate in. Sprawling was not decorous in the 18th century.” (Springs, buttoning, and other comfort-minded accessories didn’t emerge until the 19th century.) During this time, the couch was a newfound nexus of erotic energy. According to Hellman, numerous images from the 18th century depict women (and occasionally men) on couches in various states of undress, or erotic reverie, or fantasy. The couch led a sort of double life as both an enforcer of decorum and the horsehair/feather-stuffed platform for its unfettered release.

This trend took a somewhat bizarre inward turn in the 19th century with the advent of the “fainting” couch, designed to cushion the fall of supposedly dime-a-dozen hysterical women. These couches were created in combination with “fainting rooms,” which were conceived of as places to house private pelvic massage treatments for the well-to-do lady. The fainting couch had a tapered back with one raised end that created a place for women to recline while still remaining partially upright. Unlike previous sofas, the fainting couch featured only one armrest, aligned with the raised end, instead of two. This wasn’t a couch designed for two recliners: this was a place for one person to alleviate her private states of emotional and physical duress, perhaps with the adjacent company of an attending physician or therapist.

This connotation of the couch as a receptor for private distress is also evident in early Freudian psychological consultations, where it becomes a place to unburden one’s psyche. Ironically, Freud didn’t use the couch to soothe his patients as much as to soothe himself. In On Beginning the Treatment, Freud writes that “I hold to the plan of getting the patient to lie on a sofa while I sit behind him out of his sight. This arrangement has a historical basis; it is the remnant of the hypnotic method out of which psychoanalysis was evolved. But it deserves to be maintained for many reasons. The first is a personal motive, but one which others may share with me. I cannot put up with being stared at by other people for eight hours a day (or more).”

a world in which the couch had become the center of the domestic sphereAs industrialization and mass production gradually opened the doors to the formation of a middle class in the 20th century, couch design once again reflected the shifting boundaries between socially common and private realms. In this case, having elevated themselves from a Dickensian socioeconomic status, the newly formed middle class yearned for beauty and sophistication, a change that architect and housing expert Avi Friedman and David Krawitz chart in the book Peeking through the Keyhole: The Evolution of North American Homes. This was aided partly by the advent of widely produced, high-quality furniture by designers such as Ray and Charles Eames, and the emergence of television (and its unglamorous counterpart, the couch potato). Numerous modern-era couch designers, including the elegant works of Dane Finn Juhl and the modular-seating of Harvey Probber, created materially vibrant couches that were as illustrative of (newfound) mass wealth as they were of a world in which the couch had become the center of the domestic sphere. The modular couches, with their expansive wrap-around seating, were designed not for one person but for a crowd. Previously only the province of the wealthy, the couch-as-public-entertainment-foci meant that many middle class families would maintain a living room for visitors and a less formal “family room” for private relaxation.

Which is perhaps why, in an era of globalization and growing income disparity, IKEA has become such an inescapable brand. The cheaply utilitarian, assemble-it-yourself, unimposing vibe of the Swedish furniture maker has arguably manifested the mass contemporary desire for a couch that can effortlessly straddle the common and private spheres, in this case between work and home. The couch can function multi-valently as a sleeping place, a work space, and a relaxation space. Google “people working on couches” and you’ll be aswim in posed images of professionals intently working on laptops while seated (or sometimes lounging) on couches, arguably a direct result of the aughts’ Great Recession and the corresponding surge in freelancing and flexible workspaces. It helps that the incessant connectivity of the internet has all but obliterated the idea of a totally private zone. The Athena, released in 2009 and designed by Swiss furniture makers Artanova, featured an integrated computer, iPod dock, and built-in loudspeakers.

I asked Dr. Mimi Hellman if she thought that couches would increasingly display an overt “work” function because of this widespread blurring of boundaries. “I think we’re going to be seeing more and more smart furniture,” she replied. “Not just ports to plug things into, but all kinds of electronically driven features that allow for sitting in different positions, the use of electronic devices, maybe those that even allow for temperature control or firmness control. We already have the Sleep Number bed. It’s not that hard to imagine that kind of technology being integrated into other kinds of furnishings, so that they become more and more customized to that individual person’s preference and the activity that they are engaging in at that particular moment.”

Perhaps in our globalized era we are destined to return to the pre-Louis XIV days, when moving constantly was the norm, and staying put the oddity. Whatever the future fate of the couch, it seems that those who know history are doomed to redesign it.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

1 Comment

A couch is a piece of furniture that we all take for granted nowadays. Did not realize it had such an interesting history and that we have King Louis XIV to thank for its ubiquity. This article was a very enjoyable read.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.