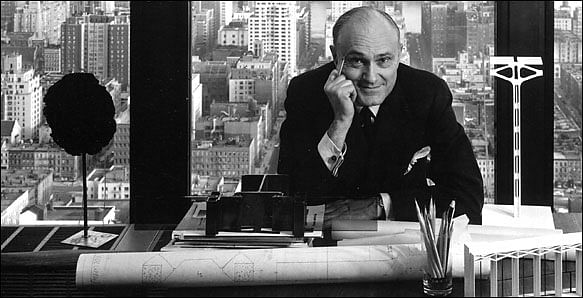

First awarded in 1979 to Philip Johnson, the annual Pritzker Architecture Prize has become the profession’s top award. But why?

How does one evaluate prestige? On the Prize's tenth anniversary, Paul Goldberger wrote in the New York Times that the Pritzker was “at this moment the most celebrated architecture award there is,” a designation that hasn’t changed since. But how did the is the Pritzker still relevant as a comprehensive measure of architectural accomplishment, or has it become too much of an insider’s game?$100,000 prize-money-bearing, bronze-medal-awarding, eight jury-membered Pritzker, founded in 1978 by Jay and Cindy Pritzker of Hyatt Hotel fame, become the top ornament on the awards tree?

Numerous other markers of distinction, including the RIBA Royal Gold Medal and the AIA Gold Medal, have been in existence for well over a century and still confer prestige upon their recipients, but unlike the Pritzker, they do not confer $100K. Of course, money isn't everything – the classical architecture-oriented, $200,000-awarding Driehaus Prize began in 2003 as something of an alternative to Pritzker's modernist sensibilities, but it isn't nearly as widely reported on. Those eligible for the Pritzker must be licensed architects who have built work that "demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision, and commitment, which has produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture." They are usually individuals, although occasionally partners receive a joint prize.

The Pritzker’s Arguably, the prize does have all the ingredients it needs to mint prestige. The problem is that the coin of the realm needs to circulate widely in order to remain relevant cash component was established as a way of creating a “meaningful prize” that would hopefully attract public attention to the profession, while simultaneously encouraging an appreciation of artistry, consistency, and vision. Often compared to the Nobel Prize for the architecturally uninitiated, the Pritzker is designed to be a widely recognized and definitive arbiter of quality and achievement, backed by substantial funds. Subsequently, the jury has often been assembled from universally recognized and lauded architectural talent: Charles Correa, Shigeru Ban, Zaha Hadid, and Frank Gehry are among the jury’s previous members, and it’s not unusual for previous winners to become jury members – sometimes, it’s even the other way around. Alejandro Aravena, the Laureate for 2016, was a juror up until the year of his win. Any licensed architect may submit a potential nominee for the prize; those suggestions are then reviewed by the Pritzker committee and narrowed down for formal considerations. The jury then meets to whittle down nominees to a single Laureate, until they arrive at consensus (the Pritzker's executive director, Martha Thorne, compared the citation process to how the pope is elected).

Arguably, the prize does have all the ingredients it needs to mint prestige. The problem is that the coin of the realm needs to circulate widely in order to remain relevant; otherwise, it risks becoming an inside job. Historically, winners are overwhelmingly male: of the 39 total Laureates, only two have been women. This has garnered much public controversy, especially on behalf of the women who were partnered both professionally and romantically with a man but did not receive recognition (see: Denise Scott Brown, partner of Robert Venturi, the 1991 Laureate, and Lu Wenyu, partner of Wang Shu, the 2012 Laureate). A widely circulated petition to award Denise Scott Brown the Pritzker retroactively was rejected in 2013, with current jury member Lord Palumbo writing that “Pritzker juries, over time, are made up of different individuals, each of whom does his or her best to find the most highly qualified candidate. A later jury cannot re-open, or second guess the work of an earlier jury, and none has ever done so.” Let precedent be your guide, Lord; conscience is overrated.

Meanwhile, worries about the Pritzker being too conservative or “safe” in its choices categorized a majority of the criticism through the 1980s – in assessing the Prize’s value on its tenth anniversary, Goldberger judged the work of all past winners as “the real test of the prize's value. the Pritzker's worth is ultimately based on how it is perceived by the public and the larger architectural community, and prestige is not immune to deflation They are a strong group, although their composition reveals a cautious, perhaps even conservative, bent among the jurors.” Around 1990, major publications refer to the Pritzker’s prestige with the inevitability of historic fact: “The annual award, known as the Nobel of architecture,” noted the Los Angeles Times in 1995; “The Pritzker Prize, widely considered architecture's highest honor,” The New York Times hedged in 1997. Or, as Architectural Record simply put it, “the profession’s highest honor” in 2008. Starting in roughly 2013, after the Denise Scott Brown petition was rejected, critics began to once again openly question the Pritzker’s right to prestige.

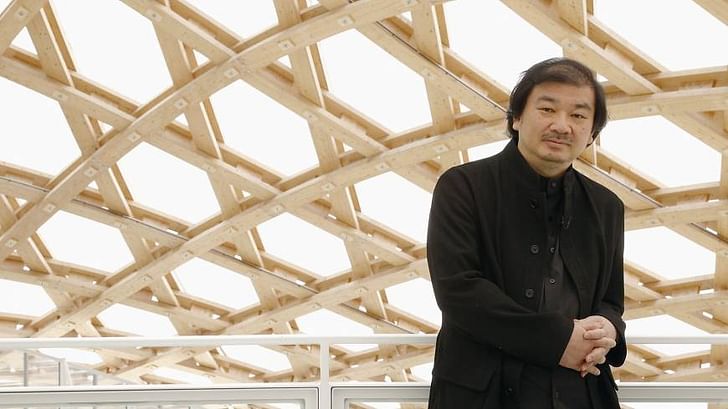

This criticism started to focus on the jury’s apparent taste for novelty. As Christopher Hawthorne wrote in the Los Angeles Times, responding to Shigeru Ban’s 2014 win for “humanitarian design”: “The biggest problem with the Pritzker, it seems to me, is its unstinting and largely unexamined emphasis on newness and novelty and therefore its connection to The biggest bias the prize has is not in favor of stars or men... but in favor of The New Thingmarketing and big business of real-estate development...The biggest bias the prize has is not in favor of stars or men (although it does have both of those) but in favor of The New Thing, an avant garde, a leading edge; and...the members of the jury have convinced themselves that humanitarian design is the leading edge.”

Viewed from this perspective, what’s critically problematic about this particular year is both the ingrown quality of the candidate and his “leading edge” quality. ELEMENTAL does, aesthetically, Pritzker-worthy work, but Alejandro Aravena was a jury member for six years prior to stepping down in 2015. The Pritzker is designed to honor living architects, and there are several prominent architects out there whose vision, artistry, and consistency quite frankly outstrips that of 48-year old Aravena (even if they haven’t served on the jury). Which raises the question: is the Pritzker still relevant as the comprehensive measure of architectural accomplishment that it claims to be, or has it become too much of a politicized, insider’s game?

Not everyone thinks that the Pritzker is overly politicized, especially when it comes to the humanitarian design aspect of architecture. In an op-ed entitled “Public Purpose of Architecture,” India’s daily The Hindu newspaper wrote, in reference to Ban's 2014 win, that “the Prize has truly met its objective after a long time…major awards, including the Pritzker Prize, thus far have favoured such less socially relevant projects. This recognition of Mr. Ban’s contributions probably marks the beginning of a rethink.” This rethink was seemingly upheld this year, as Oliver Wainwright of The Guardian keenly noted. “While Aravena has built an impressive portfolio of buildings,” Wainwright wrote, “it is the bigger strategic questions that really drive his work, and for which he has been awarded the Pritzker. The judges say he ‘epitomises the revival of a more socially engaged architect’ and gives the profession ‘a new dimension’.”

This direction in architecture may be part of why the Pritzker retains its prominence. As many critics have argued, the Pritzker seems to be reflective of an environment that values the intangible realm of political and media alignment as much as it does phenomenal built work – for better or worse. Regardless of its future, since its founding the prize has stimulated a vibrant conversation around and about architecture, bringing the profession more into public consciousness. However, the Pritzker’s significance is ultimately based on how it is perceived by the public and the larger architectural community, and prestige is not immune to deflation.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

2 Comments

Excellent piece.

It would be interesting to see a follow-up study of how the prize has effected the work and careers of the winners.

Help to sell buildings at least here in Miami.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.