In architecture, the rise of the 21st century media landscape has created connective tissue where none used to exist: the day-to-day work of architecture used to be relatively obscure, and now it is spotlighted and deconstructed regularly. The most successful architects are not those who shun this newfound audience, but rather engage with it. Of course, this poses a challenge for architectural journalists. New work must now be evaluated not only in the context of the built environment, but in the virtual environment as well.

Yet on the new media spectrum, the inanity of a Kardashian can carry the same amplitude as a seasoned columnist. Every piece is an audition. Every tweet can be a potential conversation starter, or, disappointingly, just more stale pixels lining the digital birdcage. An architectural critic–or any critic, really–must make the case for relevance daily. So how does Paul Every tweet can be a potential conversation starter, or, disappointingly, just more stale pixels lining the digital birdcage.Goldberger, the Pulitzer-Prize winning former architectural critic for the The New Yorker, current contributor to Vanity Fair and soon-to-be Frank Gehry biographer navigate the new frontier of architectural journalism?

“One has to be nimble,” Goldberger tells me in a phone conversation. As one would expect from a man who's been writing for a living for over forty years, he's precise, but warm; thoughtful, but not long-winded. The morning of our phone call, Facebook has officially announced that it will host content from The New York Times in its feed, a move that essentially erases any remaining boundary between old-school journalism and new media social networks. I've contacted Goldberger not only to acknowledge his groundbreaking canon of work, but to ask him about the state of architectural criticism, and even journalism itself as a medium.

Goldberger has thrived in this new media age by writing informed narratives that examine not just the trendy cladding of a building, but the deep historical, social, and political environments that invariably give rise to it. “If you don’t bring in the social and political, you’re basically just comparing shapes,” he says. “That doesn’t mean that aesthetics are immaterial, but you have to include the scope.” He began his career as an intern at The Wall Street Journal, and eventually became the junior architectural critic at The New York Times Magazine in 1972 – an experience he detailed in his “Building Up and Tearing Down” lecture, given in 2010. “I wrote about architecture to keep my mind engaged, since I found that I wasn’t terribly interested in editing articles about the political currents of eastern Europe, or, more often still in doing what I had to do as the low man on the totem pole, reading through the slush pile of unsolicited manuscripts.” He has now written over a dozen books, extensively lectured, and generally been recognized as one of the world’s top architectural critics. I asked him about a On the new media spectrum, the inanity of a Kardashian can carry the same amplitude as a seasoned columnistlecture he gave in which he said, “I hope that thirty-plus years in the combined battlegrounds of New York real estate and New York journalism haven’t robbed me of all earnestness.” Specifically, I wanted to know how a journalist holds on to that kind of unfeigned passion after decades of analytical thinking. “I’ve had a certain curiosity and enthusiasm, and earnestness can be a presence in my writing. I guess I’m that kind of person,” he tells me. “You can develop a sophisticated eye, but you can’t be cynical.”

"Too Rich, Too Thin, Too Tall?” a piece published by Vanity Fair last year about the rise of ultra-luxury condominiums in New York City, is among the best of Goldberger’s work. It features an almost Dickensian narrative nuance, a grounded socio-political scope, a sly indictment of the culture of narcissistic greed, and an overall linguistic beauty. The piece reads like an excerpt from a hilarious and engrossing novel. No word is extraneous, no clause misplaced, no character unnecessary. Here is context at its deepest, narrative nonfiction at its finest, and criticism at its best. It’s a triple lutz of journalism.

"What I’ve enjoyed about Vanity Fair is the ability to write these narratives,” he tells me. “The role of the critic is not to bang a gavel and say, ‘This building is guilty or innocent.’ It’s more about being a provocateur.” What of those who say that long-form architectural criticism has no place in the contemporary media landscape? “I love and believe in traditional writing,” Paul admits, “but paradoxically, we also have to admit that things are not the same. I think we have to acknowledge this reality while holding onto what we value in traditional essays.”

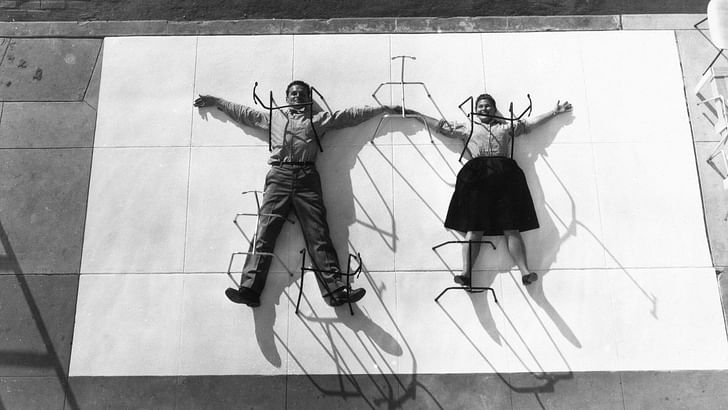

When Goldberger began his career, architectural criticism, much like the profession itself, was distant from celebrity culture. While certain designers and architects like the Eameses or Philip Johnson had managed to become household names in the 20th century, the notion of “starchitecture” was still a few decades off. Critics were grounded in years of experience and a particular educational philosophy or intellectual thought circle. When he began, Goldberger didn’t worry as much about joining a pre-existing club as directly engaging with the experience of architecture itself.“If you don’t bring in the social and political, you’re basically just comparing shapes,” he says Instead of adopting a rigid ethos, in the same 2010 lecture Goldberger explained that he wrote “about what interested me...I didn’t have a particular ideological stance other than loving the experience of wonderful buildings and wanting to communicate that, and of being disappointed when things weren’t better, and being willing to write that, too.” In 2012, he was awarded the Vincent Scully Prize and spoke about the unlikelihood of any one critic ever again attaining the influence of Ada Louise Huxtable or Lewis Mumford. "The New Yorker has no plans to replace me now that I have moved on," he said. "But on the other hand, there is the greater sense of engagement that people almost everywhere seem to have now with the built environment, the heightened sense of caring about what their houses and streets and neighborhoods and downtowns and public spaces will look like and feel like to use."

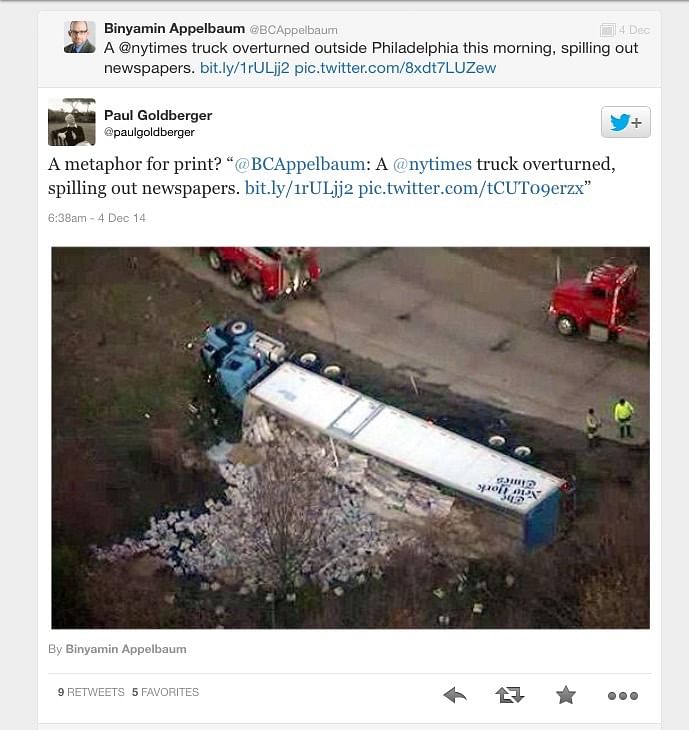

The morning we spoke, Goldberger was still mulling over a discussion he’d had on Twitter the day before. The exchange was about the new Penn Station, and how the latest iteration should be built exactly as it used to be. It was either “the smartest or stupidest” suggestion he’d heard. However, for Goldberger the memorable aspect of the experience wasn’t entirely about the proposed design, but the method of communication."We no longer discuss issues in the traditional way."With over 16,000 Twitter followers, @paulgoldberger regularly engages with his audience, replying to questions, engaging in debates, and occasionally writing 140 character Op-Eds of his own. On December 4th of last year, he retweeted a picture of an overturned eighteen-wheeler which had spilled out print copies of that day's New York Times. "A metaphor for print?" he tweeted.

Goldberger reflected that while he’s not a fan of completely unmediated discourse, he believes that our hyper-connected, every-voice-gets-a-platform age of information can ultimately be good for the larger architectural conversation. “We no longer discuss issues in the traditional way,” he says, a fitting statement for a man who has made a career out of doing exactly that.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

14 Comments

Its about time we start talking about this stuff. I'm not convinced that Goldberger has a good handle on it, but at least he's trying.

Goldberger is smart, but I've always found him to keep his finger in the wind a bit much.

“If you don’t bring in the social and political, you’re basically just comparing shapes,”

then he talks...

“about what interested me...I didn’t have a particular ideological stance other than loving the experience of wonderful buildings and wanting to communicate that, and of being disappointed when things weren’t better, and being willing to write that, too.”

It's the shapes that create the experience of the building, that create

"the heightened sense of caring about what their houses and streets and neighborhoods and downtowns and public spaces will look like and feel like to use."

Social media will die when there are no longer any old media stalwarts to leech on, real journalism to aggregate, identity battles to drive traffic and no more architecture to Instagram.

Social media will die when we stop being social.

Social media is high school but worse.... Achievers are mocked, posers are popular, mean girls are social climbing, popularity is unearned, jocks everywhere. Calatrava is hated, while instagrammers revel in failure and nostalgia.

Thats how it is in real life. Calatrava is not universally hated. Just like Bjarke Ingels isn't universally hated.

Mean girls and boys are everywhere is real life as well. Have you been to community board meetings where cranky old ladies covered in anti-war pins complain about historically inaccurate railings?

The internet just brings the cranks and the trolls closer to the Paul Goldbergers of the world.

The effect of bringing the cranks and trolls closer to the mainstream of architecture criticism is that some of the more difficult-to-understand concepts get glossed over. Try explaining Object-oriented ontology or post-Fordism to the average Gizmodo commenter or Huffpost super-user.

I just looked up object-oriented ontology and post-Fordism. I'm in.

Yeah, like I said, the nerds are kind of ostracized....meanwhile Goldberger uses the brand he's built up over many years to engage in dubious link bait debates. Except for the small corners of the internet that haven't been commodified. I'm interested in how new media can be redesigned around architecture particulars instead of high school PR junk but that's prob never gonna happen.

I think the new media is very gotcha oriented ..... And has trouble building anything real or leading change. FolkMoma failed, Egypt failed, crowd funded arch never happens, BIG, etc etc

I've always admired Paul Goldberger's support of Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. He has rightly pointed out that they have designed a unique group of "exquisite houses." I've always thought that Venturi and Scott Brown have had a special affinity for, and talent for the design of domestic architecture (not to suggest that I don't admire Fire Station #4 in Columbus, Indiana, etc.).

What I still don't understand, was his support of the Foster plan for the main research branch of the New York Public Library. Getting a Foster design in New York shouldn't have to involve so much sacrifice of historic architecture, not to mention of a research library that already functions perfectly well. Fortunately for all, further analysis revealed that the plan to deconstruct this library was prohibitively expensive anyway.

fof, Yes, sure, it makes sense that Goldberger's support of Venturi and Scott Brown could have been influenced by Scully, Stern and others at Yale. As I recall, it was Stern who alerted Scully to Venturi's work, and then came Scully's famous introduction to Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. Both Venturi and Scott Brown taught at Yale, thanks to then dean Paul Rudolph.

I doubt, however, that Goldberger did not make up his own mind about Venturi and Scott Brown. When architecture critics write, they have to really like the architecture they advocate, otherwise they would not be writing criticism, just mere reportage.

That Venturi and Scott Brown have made buildings that pay attention to composition, proportion, materials, and are wonderfully idiosyncratic, matters a lot, I think. Their best buildings qualify as real architecture. There are a lot of generic, corporate-style buildings constructed these days that cannot be so described.

f o f, Yes, I knew some of this, fascinating. I rather like Venturi's original chapel design (thesis) proposal for the Episcopal Academy.

Venturi and Scott Brown's design for addition to the Brant House in Connecticut is remarkably entertaining. VSBA moved their design aesthetic in this instance from suburban-mod green-glazed brick to English country house. Too bad Brant got cold feet, or whatever. The Brant family seems to have wanted Mount Vernon as designed by Allan Greenberg instead. Patriotic, at least.

Thanks for this, f o f, fascinating. It's my understanding that Denise Scott Brown was active in Venturi's firm quite early on, that is, before, Rauch moved on, and her name was included

f o f, Well, we certainly know that Venturi looked to Edwin Lutyens for inspiration, and has made frequent use of round-arch windows that are co-opted directly from Lutyens (see the Brant house in Vail, etc.). Venturi also said that he admired Alvar Aalto, perhaps for the Scandinavian master's more scenographic approach to plan and form (and also as a way to move away from both Kahn and Le Corbusier).

The Memorial Fountain is one of VSBA's most significant, and disturbing, designs, and, along with the proposed Mathematics building at Yale, really should have been constructed..

KieranTimberlake have built some quite interesting dormitories at Middlebury College, harking back that school's original buildings. Most firms can't muster the restraint required to do contextualism of this sort.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.