Wang Shu may be a surprising choice for this year’s Pritzker Prize, but it’s an excellent one, and well-deserved. In recent years the Pritzker Committee has gravitated towards architects who produce work with an innate understanding of place, allowing their ties to local culture to infuse their work. The choice of Wang Shu (and, by extension, of Amateur Architecture and partner Lu Wenyu) continues this trend: his work is as culturally-sensitive and contextually responsive as it is aesthetically stunning.

By keeping his practice small and his projects local, Wang Shu has developed a keen understanding of construction techniques and the capabilities of local craftsmen that allows his firm to mobilize traditional materials and formal strategies as a kind of cultural currency. While foreign architects grasp at “meaning” through facile metaphor (the profligate lucky “eight” in SOM’s Jin Mao tower, or Hadid’s “two stones” in Guangzhou), Wang Shu is able to bypass this stumbling block and avoid metaphor as a generator of form. Constrained only by the abilities of the construction workers and the innate properties of materials, Wang Shu projects an optimistic sustainability, with an emphasis on pedestrian-scale urbanism and an implicit invocation of history through the selective use of reclaimed material and the adaptation of regional vernacular formal strategies.

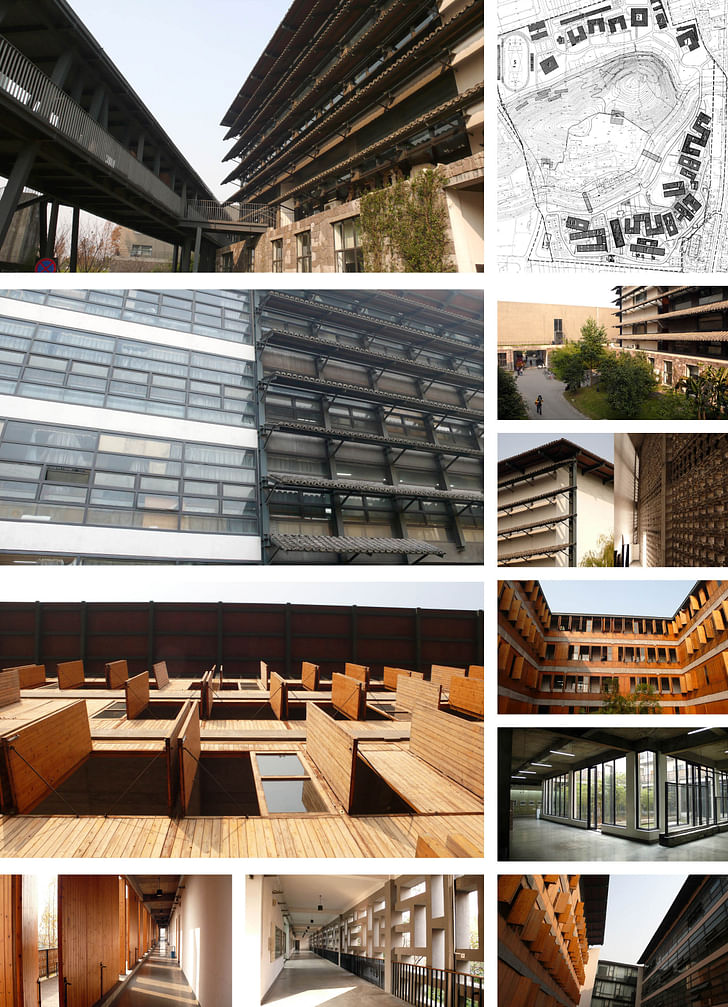

Xiangshan Campus, China Academy of Art, Phase I, 2002-2004, Hangzhou, China

Wang Shu has built only a few projects, and while the Wenzheng College Library (1999-2000, Suzhou), the Ningbo Contemporary Art Museum (2001-2005, Ningbo), and the Vertical Courtyard Apartments (2002-2007, Hangzhou) are clearly the work of a talented designer, the Xiangshan Campus is the first of the studio’s projects that is truly engaging, the product of a maturing practice worthy of the architecture world’s highest award.

The campus has often been described as an interpretation of Chinese calligraphy, with Phase One representing the geometric, standard form of the characters, and the more expressive Phase Two representing a freehand, cursive script. Though this distinction can be discerned in plan, in the realm of experience the metaphor breaks down. The overwhelming impression of the campus as a whole is one of limited material expression but infinite variety, a thoroughly contemporary construction imbued with the aura of the traditional. While the architect’s use of salvaged bricks and tiles is important, what really ties Wang Shu’s work to tradition is the adaptation of formal strategies, not the material palette.

It’s easy to assume that the courtyard configuration of the buildings in Phase one of the campus are a reference to traditional Chinese courtyard residences - but this is an archaic typology, developed independently by many cultures, borne from the fundamental relationship of humans to their environment. The advantages of this typology for a campus building are fairly obvious – the plan depth is reduced to allow for maximum daylight penetration and cross-ventilation, and each individual building wraps around a central courtyard, reducing travel distance between opposing wings and minimizing the overall footprint. The studios and classrooms are well insulated, set behind ambiguous corridors: these circulation spaces are protected from the elements only by wooden shutters. While these areas may be cold in the depth of winter, these are not spaces to linger in: the temperature gradient between circulation and program space is appropriate and represents a significant departure from the over-conditioned space characteristic of most designer architecture in China today.

While the buildings of phase one are typically identical in plan, the open ends of the courtyards face many directions, alternately framing views of the city or the nearby hill, and the façade treatment is typically determined by the solar orientation. North-facing walls are typically clad in stucco with typical industrial windows – reading as either Bauhaus-inspired minimalism, or simply as a legacy of Mao-era construction practices that favored Soviet-style international modernism. South-facing façades, on the other hand, are typically composed of the massive wood shutters, with large operable panels that animate the surface in different ways at different times of year. Each building is solidly grounded, sited atop a plinth that heightens privacy for the activities on the lower levels.

The architecture unifies the campus visually - through the limited set of materials and construction details - and physically – through the multi-level circulation network that incorporates ground level pathways and elevated walkways. Multiple pedestrian connections allow one to traverse the entire length of the campus, in good weather and bad.

While the material palette does incorporate traditional elements, they are deployed in non-traditional ways. The wooden shutters, typically small operable panels, are allowed to expand to the height of the corridor (this is even more extreme at the Ningbo Contemporary Art Museum, where the same details are used on panels three times the size). Salvaged roof tiles are applied to large louvers, supported by steel frames, and applied over a simple, modern ribbon window or curtain wall. Where these outsize steel louvers are applied to the classic modernist facades, a stark contrast is revealed between the traditional and the modern. While many cities in China have a ‘colonial’ legacy from the treaty-port era - including Beaux-Arts neoclassicism and scattered Art Deco masterpieces – the country’s typical building stock was composed of bare wood and plastered brick, or concrete in a stripped-down international style modernism imported from Soviet Russia. With all this in mind, the buildings of Phase One can be read as a grafting together of the dominant styles of China’s past.

Xiangshan Campus, China Academy of Art, Phase II, 2004-2007, Hangzhou, China

While the buildings of Phase One can be seen as a chimeric graft, the buildings of Phase Two are more of a synthesis, an attempt to reconcile these two traditions in a new vernacular architecture.

In planning and in material composition, the buildings of phase two can be understood as an elaboration of the techniques developed in Phase One. Where in Phase One, detached courtyard buildings were connected by elevated walkways, in phase two the walkways thicken, attain program and volume, and the formerly separate courtyard buildings combine into longer configurations. Where the phase one buildings were sitting atop solid stone plinths, the buildings in phase two are detached from the ground plane, floating above the grass and allowing automobile and pedestrian connections to cut through beneath. While there are no courtyards, strictly-defined, in phase two, the switchback shape of the buildings still serves to define space and create a sense of enclosure, often positioned to frame the nearby hill. As in Phase One, the buildings are constructed from a limited set of materials which are combined in different ways to produce an astounding amount of variety.

Where the courtyard typology is split apart or reconnected, the elevated walkways, sunken automobile circulation, and interior paths within each volume serve to create a three-dimensional hierarchy of space that is somewhat disconcerting to the visitor, but must be comfortingly complex to the long-term students as they mentally map the most effective navigation routes through the complex, and find the best places to spray-paint a model or pause for a cigarette. This elaboration of the ground plane is similar to the “mat” strategy employed at Candias-Josic-Woods’ Berlin Free University, and bears some similarity to the “expanded ground” of Hong Kong’s complex circulation network.

Where the phase one buildings were generally defined by a central spine of classrooms or studios, wrapped with an (occasionally) open-air corridor, the definition between interior and exterior space in phase two is more ambiguous. Exterior walkways clipped onto the facades turn at points and become interior passages; long systems of interior ramps are shielded from the elements only by thick screen walls. The interrelation between circulation space and programmed space is extraordinarily complex, like a thickening and expansion of the courtyards, screens, and covered walkways of Ming-era garden design. Where Wang Shu makes explicit formal reference to tradition - as in the sweeping rooflines that recall temple architecture – it is almost always tempered by a reconfiguration of the traditional experience – as in the walkways that lead visitors along the face of the building, denying an axial approach. The work is less successful where these quotations are merely formal, as in the jagged doorways that suggest chunky, low-resolution versions of classical garden gateways. It is spatial complexity that makes the campus so rich, not the occasional funky window.

Scattered throughout the campus, smaller pavilions abut the larger classroom buildings, and demonstrate a kind of experimental formalism in which Wang Shu and Amateur Architecture seem to be testing the limits, on a smaller scale, of the local contractors’ abilities. These small pavilions are formally ambitious and idiosyncratic in a way that makes the major buildings of Phase Two seem relatively straightforward by comparison. The architects here seems to be testing and developing their own formal language, which will reappear consistently in subsequent projects like Ningbo’s Five Scattered Houses and Hangzhou’s Zhongshan Lu Pedestrian Street.

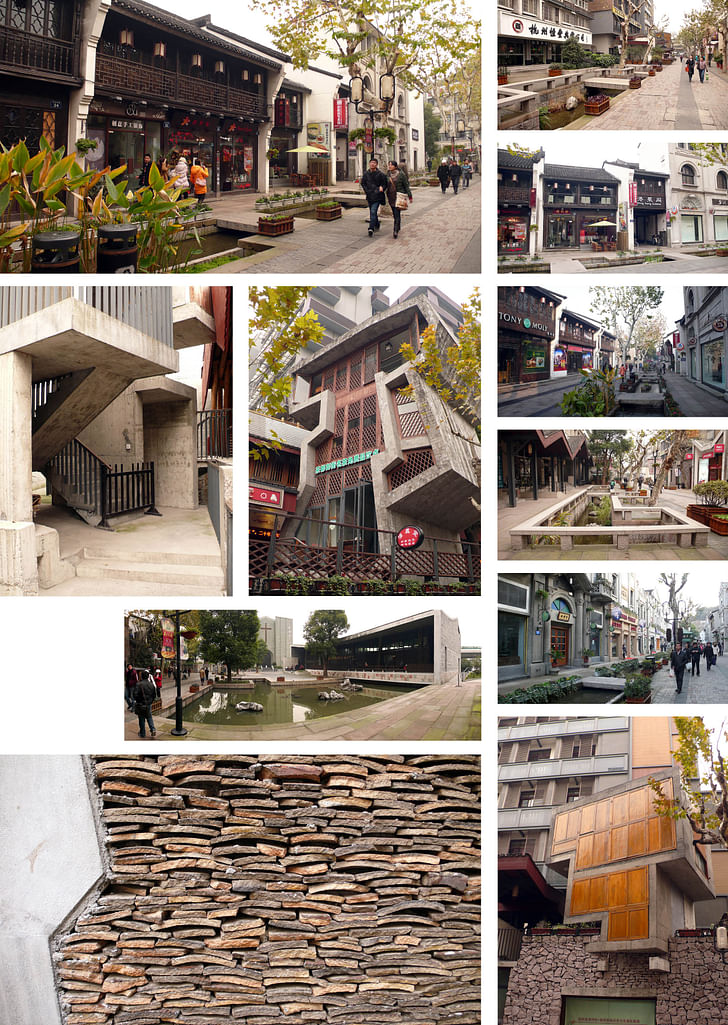

Zhongshan Lu Pedestrian Street, 2007-2009, Hangzhou

If the Xiangshan Campus shows Amateure Architecture’s abilities at the scale of a new campus, their work on Zhongshan Road shows their approach to the difficult task of intervening in an existing, loaded and layered context. Tasked with revitalizing the principal Song-dynasty axis through the city, Wang Shu and company opted for a subtle renovation that transformed the road without discarding history. Over time, Zhongshan Lu had evolved as a heterogeneous collection of styles: Qing dynasty shop fronts nestled up to Republic era neoclassical facades, the street frontage occasionally punctuated with Soviet-style housing blocks and factory lofts. Recognizing that this variety and difference were part of what gave the street its unique character and its aura of history, Amateur Architecture Studio retained most of the existing buildings and limited their intervention to the addition of the occasional pavilion and, - more importantly - manipulation of the street surface itself. Where previously there was asphalt, there is now a roughhewn stone path, sliced by shallow canals. The canals expand into larger water features flanked by planter boxes, shaded by street trees, and crossed by small stone bridges.

The canals are composed in such a way to encourage wandering – the proliferation of bridge connections ensures that one could traverse the street a hundred times and never take the same path. The shallow water ensures safety for the children who can reach down and touch the slowly ebbing stream when they tire of darting back and forth across the bridges. The canals also serve to separate the primary circulation path of the street – down the center – from the secondary – next to the storefronts. While this may have been a contentious issue for shop owners who desired continuous street frontage, the advantage is the creation of pockets of space immediately adjacent to the storefronts, ideal for the setup of a few café tables, or a semi-secure exterior merchandise stand (it’s worth noting that some shop keepers have erected their own bridges – plywood panels that span the narrow canals). The separation of pedestrian flow allows for informal shopping and leisure activities outside the main flow of pedestrian traffic.

The canals also serve to evoke the History of Hangzhou and the Yangtse delta. While Hangzhou was only the capital of one dynasty (the Song), the city was, for most of its long history, a major center of administration and commerce in an economy based on river traffic, located at the southern terminus of the empire-spanning Grand Canal. Cities throughout the Yangtze delta were canal towns, river transport being the primary economic driver for the region. While Hangzhou has lost most of its canals to infill and road widening, the use of canals here is a reminder of a long-remembered past which simultaneously provides an auditory buffer from the surrounding streets, and contributes to a cooling microclimate in summer.

The pedestrian scale of the street is a legacy of its original width, intact thanks to careful negotiation with the planning bureau on the part of the architect, but while the Song-dynasty thoroughfare may have been wide enough for carts and the occasional parade, Wang Shu has introduced pavilions to further break down the scale, and turn the street from a strictly linear axis into something more of a meandering path.

The heavy, tactile pavilions, constructed of rough concrete, traditional wood panels, and reclaimed brick and roof tiles, serve to break down the space into easily perceived segments. While each pavilion is distinct, they share a formal language, and thus the entire length of the restoration project is unified through formal and material associations (much as Parc de La Villette is unified by Tschumi’s red pavilions), each unique, but of a family.

While the manipulation of the street surface into canals, planting boxes, benches, etc, and the protrusion of inserted pavilions into the space of the street serve to create unique small-scale public spaces on a strictly local level, Wang Shu was also instrumental in the creation of a large public plaza at the southern end of the avenue, where the street passes through the old city wall. Immediately before this gate, a large water feature and plaza is framed by a mid-century church and newly constructed hall. Without the small hall, this pleasant plaza would be edged on one side by a massive highway flyover, and though the hall seems to have no specific program, its solid mass is enough to reduce the noise and odor from the street beyond. The old drum tower gate provides a clear terminus for the avenue and an ‘escape’ into the bustling modern city beyond.

Handicapping the Inevitable

When the Pritzker board revealed Beijing as the 2012 venue, I jokingly predicted that Wang Shu would win: the Chinese authorities would surely have some sway in the proceedings, if only the ability to revoke whatever permits secured the venue.

Has the recent global recession driven the Pritzker committee to celebrate elegance and simplicity over flash and gesture? When Peter Zumthor won in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, it was seen as a rejection of egoist “starchitects” and a celebration of architecture as a haptic, tectonic endeavor, with materiality and craft as the top priority. Aesthetics were to derive from the raw, natural materials of construction. Forms were to be driven by their local context and cultural traditions. As Kenneth Frampton puts it in “Toward a Critical Regionalism,” this is architecture that can “mediate the impact of universal civilization with elements derived indirectly from the peculiarities of a particular place.” Architects may find inspiration in the “range and quality of the local light, or in a tectonic derived from a peculiar structural mode, or in the topography of a given site.”

Zumthor, the mystical hermit, was the perfect prophet for the new age of austerity. The committee has been on this same track for several years now, as their intervening picks SANAA and Edward Souto de Moura demonstrate: both excellent architects, both tied intrinsically to their local cultures and traditions. In order to continue this trend in 2012, they would need to identify a practice with priorities that favored the tactile over the visual, the experiential over the experimental; those firms that best address Frampton’s call for a Critical Regionalism. There are many great firms tilling this ground – whether by philosophy or necessity – but with the selection of Beijing as the ceremony venue the board made a choice to address the seemingly unstoppable economic juggernaut in the room.

While the rest of the world wrestled with recession, China’s rise continued unabated and foreign architects followed the money. Whether they viewed China as a free, fertile ground where every fantasy could be fulfilled or as a repressive oligarchy whose absolute authority ensured audacity as a point of national pride, they were welcomed, and encouraged to indulge. Rem Koolhaas, Zaha Hadid, and Herzog & de Meuron have all benefited immensely from China’s economic dominance, contributing ambitious, signature works to the country’s rapidly modernizing cities. This image-focused attitude is still prevalent, and architects like Steven Holl still reap the benefits (if not the Pritzker Medallions) of a robust economy and adventurous clients. However, while projects like CCTV, the Guangzhou Opera House, and the Beijing National Stadium are impressive, these iconic forms are representative of an image-focused mentality that is growing less appealing as China‘s growth begins to slow.

Local architects with a better understanding of both cultural context and construction capabilities are – thankfully - gaining prominence. This can’t be a bad thing, as China must seek regionally-appropriate, culturally-sensitive design solutions if it wishes to slow the homogenizing trends that threaten to strip China’s rapidly-modernizing cities of their unique urban character.

So, if the committee felt the need to celebrate China’s rise, but not coronate a vacuous “starchitect” – who would be the winner? There are other excellent Chinese firms, but few fit the “Zumthor profile” (Liu Jiakun comes to mind). Others were either out of the running (FCJZ’s Yung Ho Change was on the Pritzker Jury), or too obviously controversial (Ai Wei Wei’s FAKE Design). The selection of an architect born in Urumqi, educated in Nanjing, and based in Hangzhou sends a clear message: this prize not only recognizes the great work being done in China, but is a validation of the efficacy of the Chinese university system, and a celebration of the government and economic system that makes such great work possible. If the selection of Wang Shu was politically motivated, so be it: it does nothing to diminish the power of the work or the relevance of the firm.

In this “age of austerity,” Wang Shu’s designs represent a vital and promising path forward that doesn’t deny the past. It is a projective austerity – an optimistic recognition of current limits that hints at future potential and provides a clear outline how to achieve it, not instantly but with practice, repetition and the development of easily deployed formal strategies that could serve as a model for architects who base their work on a similar philosophy.

This is where the work’s power really lies: in its ambitious (and ambiguous) synthesis of the contemporary and the traditional. Technology-driven form-making and traditional construction techniques are used in tandem. The attitude toward history here suggests a way forward for Chinese architecture that doesn't rely (solely) on flashy renderings and iconic forms, but can retain those essential qualities of the historical fabric that make China's ancient cities so appealing, those qualities most endangered by the rush of modernization.

The recognition of Wang Shu as 2012’s Pritzker Laureate is a welcome and necessary choice if China (and the world) is to recognize the value inherent in carefully-considered, culturally-sensitive work, and build a global design culture based on meaningful intervention, not empty icons. The work of Amateur Architecture points toward the future without abandoning the past, and reclaims China’s great architectural heritage through new synthetic models, new archetypes, and ultimately a new vernacular.

Evan Chakroff is an architect and critic based in Seattle. With a background in engineering and over 10 years’ experience in world-renowned architecture firms in the US and abroad, Evan brings a multi-disciplinary, international perspective to his work. Evan’s architectural criticism ...

4 Comments

Very nicely done. I hadn't really thought of the political implications of the pick as you describe " The selection of an architect born in Urumqi, educated in Nanjing, and based in Hangzhou sends a clear message: this prize not only recognizes the great work being done in China, but is a validation of the efficacy of the Chinese university system, and a celebration of the government and economic system that makes such great work possible. If the selection of Wang Shu was politically motivated, so be it: it does nothing to diminish the power of the work or the relevance of the firm."

Also love the idea of a new vernacular of projective austerity....

this work is far more sympathetic to local vernacular, climate, and materiality and more humane than a lot of the very aggressive work we've seen out of the architectural superstars in the past decade. I hope this is the direction we're headed.

Thanks Nam.

That is some beautiful work.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.