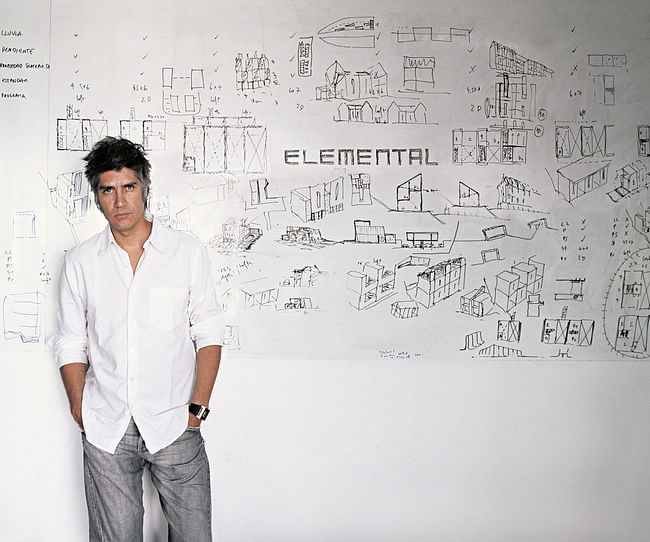

What to make of this year’s Pritzker Prize awarding? With today’s announcement, the Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena has secured his place within the upper echelon of the architecture community. In fact, 2016 is shaping up to be his big year: he’s curating this summer’s Venice Biennale, which is expected to be something of a showcase for the type of high-design yet socially-aware and economically-pragmatic practices that his own “Do Tank,” Elemental, typifies.

Often touted as an antidote to the 1%-er friendly era of iconic “starchitecture,” so-called “socially-aware” architecture is having a bit of a moment. Many of the practices highlighted in last year’s Chicago Biennial have been labelled as such, in spite of the absence of any real unifying theory or set of practices among them, and this year’s Turner Prize was historically awarded to Assemble, a group that tries to employ design to improve living conditions in economically-marginalized areas of the UK.

Aravena is often seen as the “poster child” of this indeterminate yet visible architectural trend, as Oliver Wainwright notes in the Guardian. As such, this year’s Pritzker awarding has quickly become a sort of architectural black mirror – a means to foretell future trajectories for the disciplines that, in all likeliness, reflects the scryer’s own biases more than anything else.

The Los Angeles Times has generated some of the most substantial coverage yet, beginning with a back-and-forth between architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne and his colleague, arts columnist Carolina A. Miranda, who had included Aravena in a profile of Chilean architects published last year by The Times. Their conversation attempts to understand the implications of the awarding for both the prize and, more broadly, the profession.

This year’s Pritzker awarding has quickly become a sort of architectural black mirror – a means to foretell future trajectories for the disciplines that, in all likeliness, reflects the scryer’s own biases more than anything else

“With a few (but only a few) exceptions, [the Pritzker has] honored men at the expense of women; individuals at the expense of pairs or collectives; architects who work for wealthy, establishment clients at the expense of those working for the poor or disenfranchised; and north over south,” Hawthorne notes. With this year’s awarding, it moves away from the latter two categories but not the first two. “A modest move in a different direction, let's say,” he states.

Hawthorne and Miranda both seem to find the awarding as symptomatic of an awkward transitional phase for the Prize, which is not-so-easily adapting to a changing political climate as well as economic and professional restructuring. “…Increasingly it seems the Pritzker has to do one or the other: try to adapt to a shifting definition of architecture or stick with the career-achievement model,” Hawthorne writes.

“I do think Aravena is a compelling Pritzker candidate: The scope of his work in the south of Chile is ambitious and important because it represents an architect who is thinking holistically about environment, not just buildings,” states Miranda. “But it would have been better for him if the jury had put at least a year’s worth of breathing room between his service on the Pritzker and his selection for the award.”

Writing for the Dallas News, Mark Lamster echoes this sentiment, finding the timing “indicative of the Pritzker’s historic inability to get out of its own way,” while contending that Aravena’s work still merits the prize. That Aravena served on the cozy, tight-knit Pritzker jury for 7 years, only stepping down last year, invites suspicion and skepticism – in truth, probably more than has been voiced so far.

Yet by and large, most commentators have focused on the apparent political orientation of Aravena’s practice rather than the politics of the jurying. In a separate article for the LA Times, Hawthorne contextualizes Aravena’s early development in insular, Pinochet-era Santiago. “Combined with the geography that has always kept Chile physically isolated, wedged between the Pacific Ocean and the Andes Mountains, that political climate was enough to make Aravena and his classmates feel as though the rest of the architecture world was a million miles away,” he writes. Today, Aravena has moved just about as close to center as is possible.

Most commentators have focused on the apparent political orientation of Aravena’s practice rather than the politics of the jurying

But while he may be at the center of the architecture world, his politics are left of center – although not tremendously. Aravena is more a pragmatist than a radical, despite what some architects and writers may want to think, and that’s been part and partial to his success. “Everything we do is for profit. Even the social housing we do is for profit,” he has said. “Social housing required professional quality rather than professional charity.”

Still all coverage, without exception, has made note of the apparently political character of his work and, in a special interview with Dezeen, this takes central focus. The architect expresses surprise at the awarding – in spite of his close relations with the jury – and explicates the two primary foci of his practice.

The first stands “as far away from architecture as possible,” he purports, comprising a broad consideration of urban issues “that every single citizen understands,” ie. segregation, congestion, pollution. The second focus is temporal: how to stay in step with the zeitgeist, while producing work that will stand up to the test of time.

“So there's two things,” Aravena summarizes. “On the one hand being sensitive and connected to the moment that you live in, and then responding to that with a proposal, with a design, that is able to stand the test of time.”

Other highlights of the interview includes Aravena’s take on the insularity of architectural discourse; his predilection for “open system,” participatory and incremental design; and his ready refusal of control. “Architecture is an expression of needs and desires and forces that are outside yourself, be it a government, a private person or a community,” he states.

Architecture is an expression of needs and desires and forces that are outside yourself, be it a government, a private person or a community, according to Aravena

Writing for Vanity Fair, Paul Goldberger, like others, strives to understand what this year’s awarding means for the Pritzker, while also praising Aravena’s work and social orientation. “Giving a dark horse like Aravena the Pritzker two years after Ban suggests that the Pritzker jury is casting its lot with social responsibility over celebrity—although, in truth, these things do not have to be incompatible,” he writes.

Wainwright echoes this sentiment in his write-up for The Guardian: “It is a refreshing choice for the Pritzker, usually awarded to later-career architects whose portfolios brim with grand cultural monuments.” As does Alexandra Lange, in her exuberant review on Curbed: “The selection of Aravena codifies the direction in which the Prize jury first feinted with the selection of Shigeru Ban in 2014—a direction, it must be noted, in which Aravena played a part as a juror.”

“The work is easy on the eyes as well as comfort for the soul,” Lange continues, later describing his institutional work as “pre-ruins, with deep, shade-creating facades, generating the kind of monumental, sheltering spaces found at La Tourette or the Indian Institute of Management.”

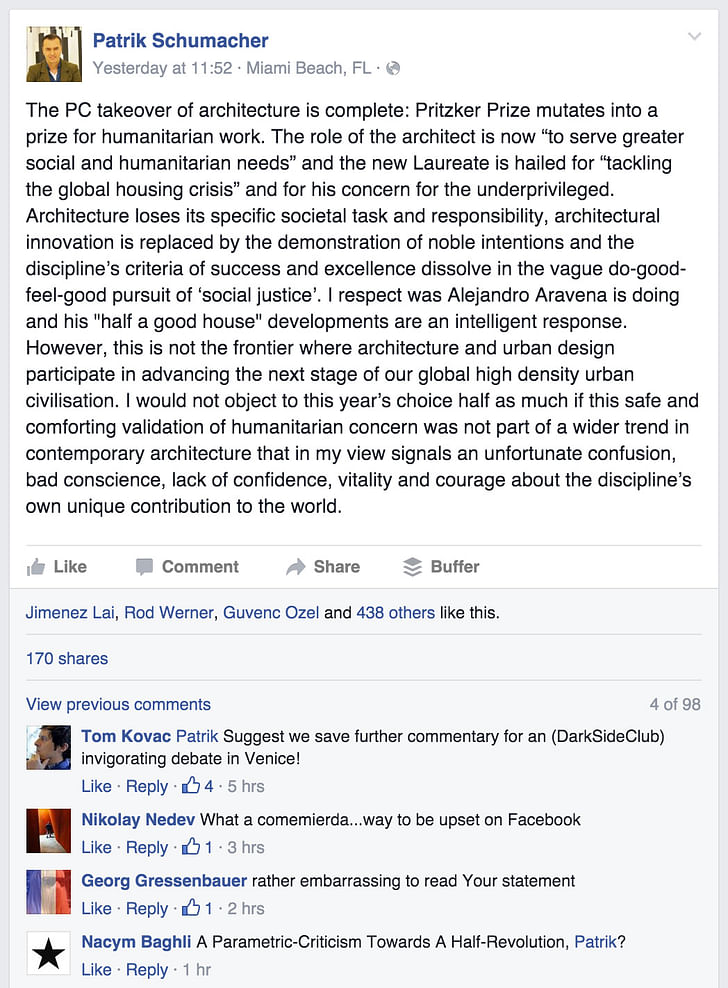

In fact, besides all the tepid criticism directed at the Pritzker itself as an institution, most commentary seems to praise their decision. The most vociferous criticism comes, unsurprisingly, from Patrik Schumacher who took to Facebook to voice his grievances.

If architecture has, in recent years, becoming increasingly concerned with its own political position, it is likely a reflection of a changing global context in which fame seems only possible through complicity with the financial elite (at best) or dictators (at worst).

“The PC takeover of architecture is complete: Pritzker Prize mutates into a prize for humanitarian work,” he begins, before continuing with a now-typical diatribe against what he perceives as a misdirection for architecture. Schumacher has written extensively on his Facebook before, both in defense of his own notions of architectural innovation and against the apparent “social turn” evident in the discipline in the last few years.

On Twitter, Schumacher’s rant generated some laughs – from Catherine Slessor, for example, as well as Wainwright – and a few more serious responses. “Humanitarian? Or clever co-optation & conversion of struggle into social/financial capital by Aravena & Hyatt corp?” ventured Susan Surface, an architect and the director of DiPSeattle.

If architecture has, in recent years, becoming increasingly concerned with its own political position, it is likely a reflection of a changing global context in which fame seems only possible through complicity with the financial elite (at best) or dictators (at worst). Even below the firmament of household names, every architect today finds herself working in an increasingly global economy, the form and function of which she has very little control over. Alongside this, global warming and other ecological crises have forced professionals to confront their own ethics regarding consumption and waste, as well as more broadly their position within enmeshed ecology – a necessary if fundamentally intractable imperative. Add the rapid, world-encompassing discursive forum of the internet and, suddenly, every site becomes impossibly expansive and porous, every architecture project nonlocal, or not-entirely-local.

In this context, architecture can appear as paradoxically both #mostimportant and #irrelevant. Politics, economy, ecology are each seen as either inside or outside the domain of the discipline, depending on one’s point of view. For Patrik Schumacher and the like, the so-called “social turn” comes from bad conscience – from an inherited sense of guilt – and distracts from both the proper domain of architecture and its true potential, ie. formal innovation.

Architecture can appear as paradoxically both #mostimportant and #irrelevant

For others, this turn marks a necessary shift in thinking towards addressing the real, if accidental, effects of architecture – waste, pollution, social inequity, enforced gender norms, and so on. It marks a moment when architecture can become unshackled from patronage, from the wealthy elite, and its practitioners’ talents can be finally co-opted for the common good.

But there is also a good deal of validity to Schumacher’s perspective, even if you don't share his politics or his predilection for parametric software. This is not to say that Aravena is not an accomplished architect or undeserving of the Pritzker. But, to venture a similar critique from a different political orientation, such architecture practices risk ending up a palliative: a means to feel that architecture, in general, is a social good, perhaps even capable of solving serious social issues, despite still operating within a fundamentally unjust global context.

A well-designed, affordable housing project might improve the lives of several – even hundreds – of families. But no design can really address, let alone change, a global system of unequal wealth-distribution that forces billions to live in inadequate housing conditions. In essence, these practices amount to a “folk political” architecture, which grants primacy to projects with immediate – and photogenic – results rather than efforts at systematic change. While projects like those by Aravena may have good, local effects, they are more band-aids then cures. Even if every architect in the world endeavored to practice similarly, the larger conditions that create these social, political, and ecological issues would remain largely the same. Of course, systematic change is largely acknowledged as outside the domain of the discipline – but, then again, the potential for a revision is at the very heart of the question and the awarding.

What does it mean when arguably the two most preeminent institutions in the architectural world – the Pritzker and the Venice Biennale – confer authority to a mode of architectural practice applauded, specifically, for its political orientation? Is this the architectural equivalent of awarding Obama the Nobel Prize his first term in office? Or a truly radical shift in direction? This summer Aravena will have the opportunity to prove the merits of this still-nebulous and undefined direction within architecture.

While architects should certainly address social issues in their local contexts – and there is certainly room for both local and globally-oriented initiatives – it remains important to avoid disciplinary self-satisfaction and inflated self-importance, particularly when we still consider a bronze medal conferred by an international hospitality conglomerate as among the highest achievements possible.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

14 Comments

Politics will always be measured in its distance from reality. If you look at at an average house from the 1920s, it is built with care (and love). Many buildings today, for the rich or poor, are built with neither, substituting narrative or spectacle for quality. It does seem like AA is building his with care, and with some kind of $ backing. Is it empty political rhetoric? Hard to say, but pictures do say a lot. The critical response, however, says very little other than repeating a narrative (amazing how a prominent figure in the field was never written about other than by the LATimes?). Media stinks.

What Schumacher sees as a devaluation of the architect: [to] "serve greater social and humanitarian needs" is in fact a compliment to and reevaluation of our profession. If architecture would be about using the most trendy software and avoiding 90 degree angles like the plague...he might have a point. Luckily architecture is more than that.

Aside from politics and purpose, I find AAs work much nicer aesthetically than ZHA.

Patrick is playing devils advocate. I'm not sure he really believes his own position. Seems more like he choose the "bad guy" character because that was a theoretical road less traveled.

it's always a few uninformed voices commenting about generalizations like where he's from, what he looks like. Are there any serious critics out there? Has anyone even seen the work? Even Patrik Shumaker doesn't offer a serious analysis of the work, only a comment on "PC culture" whatever that means

Now that Alejandro Aravena is institutionalized, there is still a chance to redeem himself by sending a homeless person to deliver his medal speech.

Btw, we need this to happen again at the Oscars in 2016 as well.

it would be really great to do an article on the situation of housing in Chile, what Aravena does is not oriented to end or palliate homelessness at all, but to provide better alternatives to government built housing as is managed today. He's not out to solve the housing "crisis" in the world, but to install an agenda in which these issues are equally addressed with whatever it is the trends are doing.

There are always critics who have a point but then, the role of an architect is not the one of a politician, and even less that of a superhero. We will never end homelessness but we can provide housing solutions that procure not only dignity but that also fulfill the spiritual needs of the people, and Aravena does that. Maybe for many that's not enough to be deserving of the Pritzker Price, but his awarding definitely sends a political message to everyone in the industry; we should care about things other than the aesthetic and business sides of the profession.

Keeping politics aside, 'Livability' is the pre-requisite not creating ginormous monumental structures on this planet. So, if somebody does find innovation in affordability and an approach to common people, no matter how ordinary they can be in front of fancy designs, they are still above all paradigms of present society.

During my Thesis(Affordable Housing) sem, I have closely studied his work on providing affordable, climate responsive, incremental housings to common masses which I found very inspiring. It guided me to understand the practical and compassionate approach to Architecture.

This article spins out a bit at the end. Let's take a step back. Probably, if he did not also create beautiful buildings, then his work on the humanitarian side may not have been enough to win a Pritzker prize. I see his work more broadly working in a both-and scenario, where he is willing to deliver high quality, high priced buildings as well as high quality, low priced ones.

In regards to affecting broad social change, I would say that intelligently creating communities for poor people to become less poor, open up loans for business backed by the increasing value of their state subsidized house, and create a better life for their families is exactly the definition systematic change: slow and generational.

More to your point about " we still consider a bronze medal conferred by an international hospitality conglomerate as among the highest achievements possible." I think this is exactly what makes the Pritzker prize appointment great. ELEMENTAL is creating an accommodating experience not only for the rich but also for the poor. To say that there is a shift away from something I feel is missing the point.

It seems more like the Pritzker prize is looking to add another layer to the understanding of the Architect. It is saying, yes do beautiful work, yes create something truly innovative, but also connect your brilliance to both the rich and the poor.

A great architect!

Good for the Pritzker. I don't see what all the angst is about. This guy's an insider from my reading, but it all can't go to the guy with the shinny objects and authoritarian manner. Hopefully this means the Pritzker is paying attention to the street as opposed to being a mouth piece for academy, but I doubt it.

Schumachers response feels to me like Donald Trump calling out Bernie Sanders for receiving the Democratic nomination.

Maybe Schumacher should debate Alejandro and have Wolf Blitzer moderate -

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.