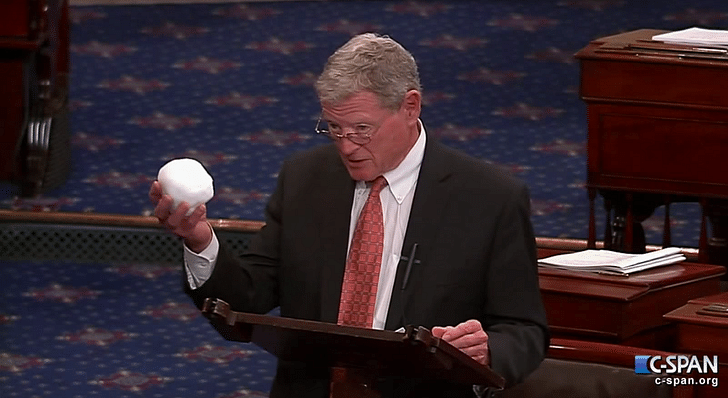

Jim Inhofe, the senior Senator from Oklahoma, resumed chairmanship of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works in early 2015, following an eight year hiatus. Shortly after, he stood on the Senate floor holding a snowball sealed in a plastic bag. "In case we have forgotten, because we keep hearing that 2014 has been the warmest year on record,” Inhofe began, taking the snowball out of the bag and chucking it across the room. “You know what this is?”

Indeed, while 2014 registered as the warmest year on record globally, the Washington D.C. area paradoxically faced some of the coldest days in memory. This happens a lot. Just one year before, a similarly fierce winter storm pummelled New York, prompting current Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump to tweet:

This very expensive GLOBAL WARMING bullshit has got to stop. Our planet is freezing, record low temps,and our GW scientists are stuck in ice

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 2, 2014

Congressman John Fleming of Louisiana posted a link to a report on the storm, adding, “‘Global warming’ isn't so warm these days.” And a few years before that, following President Obama’s second inauguration, the current House Majority Whip, Rep. Steve Scalise, commented, “I found it ironic that the President was wearing a trench coat it was so cold, but he's talking about global warming.”

Currently, over 56% of Republicans in Congress – 169 members – deny or question anthropogenic climate change. In this, they tend towards one of two logical fallacies. The truism, “I’m not a scientist,” characterizes the first: something like an inverse appeal to authority, in which willful ignorance is presented as a valid approach to an issue – not to mention a job – that constitutively demands study. The second, illustrated by the aforementioned quotations, deduces a broad generalization from anecdotal evidence. More to the point, it mistakes apples for oranges: weather is not climate, just as a political science isn’t a hard science. Weather is not climate, just as a political science isn’t a hard science

Despite the absurdity of these rhetorical strategies, and putting aside their potentially grave repercussions, they also help identify a salient characteristic of global warming: it’s very difficult, if not impossible, to perceive from a human vantage point. In scale and scope, timeframe and complexity, it’s so far beyond anything we’re used to that we can barely even wrap our heads around it. Two recently published volumes (with oddly-similar pink-purple covers) present different, if overlapping, takes on the perspectival shifts necessitated, or imposed, by global warming. The Geologic Imagination, published by Sonic Acts Press and edited by Arie Altena, Mirna Belina, and Lucas van der Velden, is “an attempt to imagine what it means to live in the Anthropocene, in a world where climate change – a catastrophe for humans – is irreversible.” The Underdome Guide to Energy Reform, edited by Jeanette Kim and Erik Carver and published by Princeton Architectural Press, “catalogs ideologies behind energy rhetoric to enable participants in the building process to make informed choices and identify allied approaches.”

Both editions are statedly sited within the ecological reality of today; they are reactions to, and modes of operating in, an era marked by the co-constitutive issues of climate crisis and resource depletion. They’re also both the textual components of other projects. Sonic Acts is “an organisation for the research, development and production of works at the intersection of art, science and theory.” It hosts an annual festival in the Netherlands, and The Geologic Imagination is as much a guide to their 2015 event as a stand-alone volume, including transcripts of talks as well as a thumb drive with a sound work by BJ Nilsen. Global warming is one facet of an increasingly-apparent reality often described using the term “enmeshment,” meaning, in short, that everything is connected.The Underdome Guide to Energy Reform, on the other hand, is a translation of a website into print, and includes transcripts of the Underdome Sessions, a series of panels held at Columbia University’s Studio-X in New York. The two books also help illuminate some of the difficulties in perceiving climate change, while offering some potentials for movement.

For one, it may not be immediately evident what a guide to energy reform has to do with global warming. But global warming is one facet of an increasingly-apparent reality often described using the term “enmeshment,” meaning, in short, that everything is connected. We can’t just immediately ban the use of fossil fuels – which would assuredly grind the global economy to a stop – but rather have to employ a diverse arsenal of tools and strategies that include, yes, burning petrol. Not only that, as is increasingly made obvious by the lack of any international consensus on how to act vis a vis climate change, ecological enmeshment is constitutively woven into the mesh of the global economy. Right now, a tiny Scandinavian country might be able to eliminate carbon emissions, but India, as it attempts to move beyond industrialization, certainly cannot (and will not). All the more reason to depict “energy reform as a landscape of competing agendas,” as the Underdome Guide seeks to do, so that new arrangements of various strategies can be formed, particular to each region and constituency.

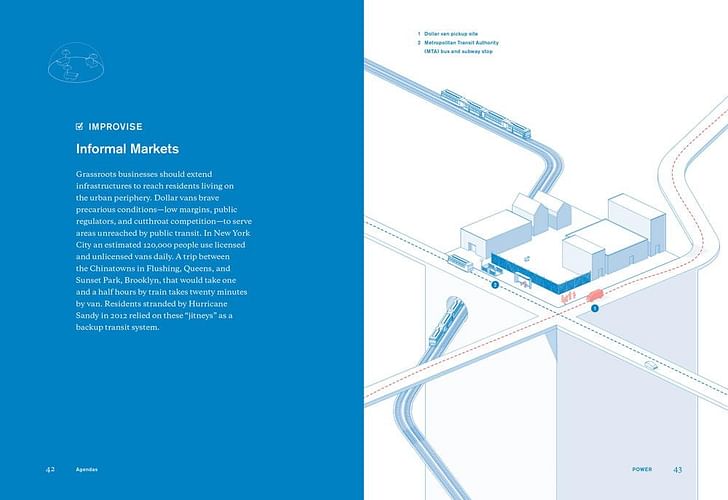

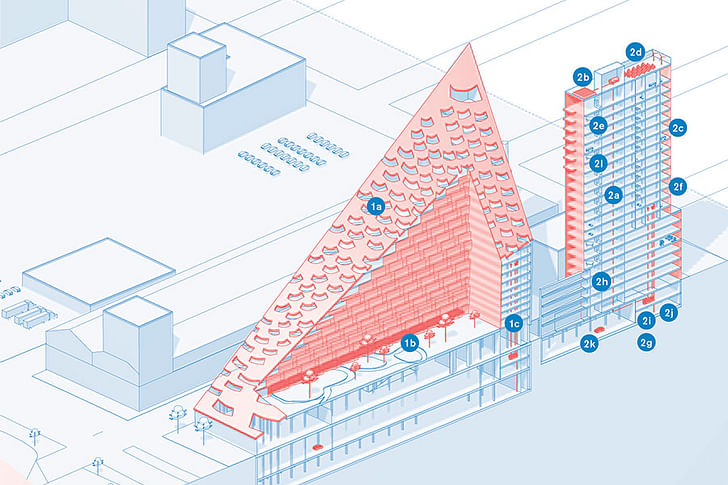

For practicing architects or planners, the Underdome Guide to Energy Reform promises to be a useful, perhaps indispensable, tool. The book, organized into four sections, identifies various approaches to energy reform and management, mapping them according to ideology. The designers allocate one spread per approach, with the left page containing a short descriptive text and the right, an elegant graphic. Essays and the transcripts of a series of roundtable discussions punctuate the sections. “Can systems thinking be expanded from energy consumption to the complex network of forces and actors at play in the city today?” asks Georgeen Theodore in an essay that critically revisits Buckminster Fuller and Shoji Shado’s 1960 “Dome Over Manhattan” project. Can systems thinking be expanded from energy consumption to the complex network of forces and actors at play in the city today?

The idea of enmeshment also plays a central role in the Geologic Imagination, a large-format book stuffed with a wide range of material, from essays to interviews to photo essays, that map out a diversity of emotional and intellectual responses to the Anthropocene and its signifiers. The project actively invokes the theorist Timothy Morton’s concept of “dark ecology,” which implores resisting the cushy feelings of mainstream sustainability or “back-to-nature” posturing. Instead, this mode of ecological thinking understands humans as interconnected to not just beautiful forests and cuddly animals, but also radioactive sludge and industrial waste. The book opens with a photo essay by Marijn de Jong, depicting the strangely beautiful juxtaposition of toxic industry and arctic landscapes in the Kirkenes region between Norway and Russia. In an essay entitled “Poetry and Beekeeping,” the geologist Michael Welland writes, “...Science today not only rejects any disconnection between ‘us’ and ‘everything else,’ but rather emphasises quite the opposite.”

The mise-en-abyme-like appearance of enmeshment, wherein ecology and economy are revealed as co-constitutive, is well-discussed in a conversation between Tim Maughan and Liam Young, as they travelled along the Korean, Chinese and Taiwanese coasts aboard a massive Maersk shipping freighter. Alongside Kate Davies, Young leads the Unknown Fields Division, a nomadic design studio operating out of the Architecture Association that travels to the extreme landscapes produced by the globalized economy (full disclosure: I accompanied the Unknown Fields Division on a recent trip to Chile and Bolivia, looking at energy futures). The shadow cast by the luminous screen that we hold in our hands stretches across the planet, it stretches from the wind farms, stretches across to this area of mineral mine in China, and to a toxic lake in Batou“The shadow cast by the luminous screen that we hold in our hands stretches across the planet, it stretches from the wind farms, stretches across to this area of mineral mine in China, and to a toxic lake in Batou,” Young states. But Young and Davies’ focus isn’t just documenting this situation. As Young explains, “We’re all wrapped up in this massive network of industry and infrastructure and it’s important to talk about our complicit nature in it, because then you might start to relate differently to it. You might start to think about it in new ways.”

Far from occluding vision, emotion can clarify the relationship one has to complex ecological issues, at least according to many of the texts in the Geologic Imagination. “It’s entirely legitimate to say that I’m worried about climate change, and that’s a mood,” states the historian Dipesh Chakrabarty in a transcribed conversation with Liesbeth Koot that touches on a wide variety of issues – in particular the human emotional registers produced by climate change. “It’s legitimate to say that I feel sad about what human beings have done to themselves. And this has to be acknowledged, instead of creating policy that is in the tradition of saying ‘my policy is just scientifically rational.’”

The Underdome Guide to Energy Reform is far too certain of the value of neutrality to wax emotive. After all, it endeavours towards a clear-eyed look at all the various strategies currently on the playing board of energy reform. But, it understands the importance of the individual’s stake in an issue. “Lifestyle,” the third of its four sections (the others are: Power, Territory, Risk), “looks at sociability and the individual.” With reference to projects from such practices as Bittertang and BIG, the sections seems to ask: can designers help us get psychologically-prepared for inevitable futures? Or could architects, through design, encourage communal living? Or alternatively, self-sufficiency? Without a singular ideological agenda – besides juxtaposing others – the short blurbs form something of a comparative study. What would it take to stage a lifestyle intervention, to really put efficiency and innovation on the couch? The advantages of reinvesting in nuclear families prefaces a call for nontraditional households. “What would it take to stage a lifestyle intervention, to really put efficiency and innovation on the couch?” the authors ask. During a time when vitriolic resentment for an opposing camp tends to outweigh concern for the issues at hand, the approach of the Underdome Guide to Energy Reform feels not just refreshing, but urgent.

Over the past few decades, architecture has birthed a bevy of modifiers and adjectives: sustainable, green, landscape. Unfortunately, their outputs largely remain inadequate at best and palliative at worst. There’s the aesthete camp, armed with green roofs and recycled timber cladding, that can often do more harm than good. There’s the austere contingent, with their holes-for-toilets and twee microhouses, who present neither a scalable solution nor an appealing product, alongside their inverse, who hijack the discourse and its strategies to simply make a buck. And there are the many, both high-profile and low, who’d rather just wash their hands of the issue entirely.

But, ultimately, the apparent deficiencies of these strategies says less about their authors than to the profound complexity of the problem. In short, the same slippery quality that feeds climate change deniers also makes it really difficult to respond to them with ready and applicable solutions. In part this is because we remain under an epistemological regime that models understanding around epiphanies – the St. Paul on the road to Damascus moment, the light bulb illuminating overhead – while the increasingly evident reality of climate crisis that none will emerge because, frankly, it’s too complex, too already-happening. Planetary systems just don’t work the way Hollywood movies do, and it’s as foolish to imagine a one-size-fits-all architectural solution as it is to hope for a spandex-clad muscle man to swoop down from the heavens. Planetary systems just don’t work the way Hollywood movies do If we’re going to adapt to this situation, we’ll have to learn to be okay with phenomenon that exceed the scale of our own lives, of strange and even uncanny conceptions of time, space, and responsibility.

The Underdome Guide to Energy Reform and the Geologic Imagination present two different attempts to expand the limits of thinking in the light of unprecedented ecological issues. The latter unpacks the sometimes awe-inspiring, sometimes awful emotional rollercoaster of life today, as beings increasingly aware of what it means to be tethered to a planet that may become inhospitable for us sometime in the future. The former reflectively analyzes the tools we have at our disposal to maintain habitability, astutely dancing around the traditional ideological hang-ups of both architecture and environmentalism. Together, they prove that there are indeed new ways of seeing appropriate to this era – they just require a polyphony of voices.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

1 Comment

Regarding your full disclosure, have you written up/produced anything about/from your participation in the 2015 Unknown Fields Division "Lithium Dreams" expedition?

Perhaps it comes up in the latest Archinect Sessions One-to-One #4 with Liam Young? Haven't had a chance to listen yet...

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.