Rarely do any two people share an identical Los Angeles. From the unsentimentality of Joan Didion to the romantic corruption of James Ellroy to the hyperbolic insight of Mike Davis, LA's urbanity is fundamentally idiosyncratic. Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles, written by Guggenheim Fellow and Los Angeles Times book critic David Ulin, recognizes and celebrates this disjunction. By richly layering history and personal observation, Ulin unspools the divergent threads of LA one walk at a time, exploring not only his relationship to the city, but the city's relationship to itself.

Calling David Ulin an incandescent writer is like noting that Mount Everest is tall. What’s noteworthy about Sidewalking is how he manages to contain the seemingly uncontainable scope of Los Angeles in seven concise chapters, from its architecture to its films to its fragmented je ne sais quoi. Each chapter (except for the cinematically-oriented “Falling Down”) begins in a real physical location and then gradually meanders out into a conceptual stroll. The chapters echo quotes from another, creating a rippling cycle of observation that laps further into unexplored territory, until, by the end of the work, it coheres powerfully.

This structure is not accidental, as Ulin told me over the phone one afternoon. “I like writing that operates that way, I like trying to weave those things,” he said. “There’s always for me a really interesting relationship between preparation or structure on the one hand, and serendipity or chance or unknowing on the other hand. I want to make room for both of them.”

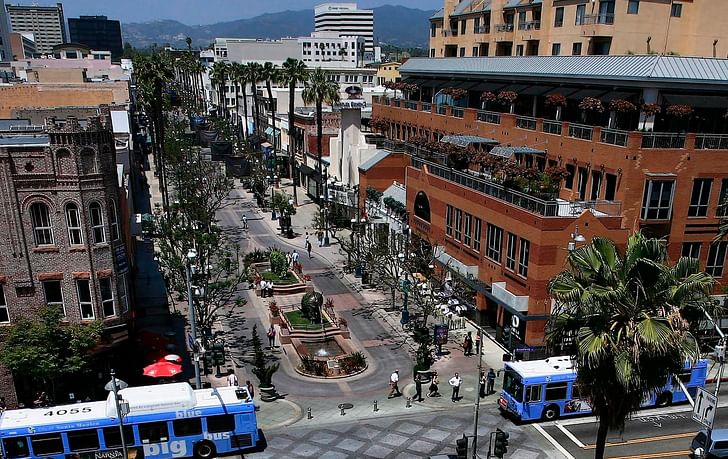

And what is Los Angeles, if not a serendipitous place? The low-density nature of the beast has often meant that public space crops up more by happenstance than planned occasion – unless The chapters echo quotes from another, creating a rippling cycle of observation that laps further into unexplored territoryof course you’re a developer like Rick Caruso, whose mixed-use retail complex The Grove Ulin mercilessly, but thoroughly, examines in the book’s titular chapter. “It is the kind of place I’m wired to hate,” Ulin writes, “ersatz, a contrivance, a cross between a mall and Main Street USA at Disneyland.” However, Ulin reflects that in actual use the Grove is “a laboratory, a training ground...what’s important are less the intentions of its builder than its integration into the life of the city of which it is a part.” This allows him to jump into a historical exploration of LA’s “private urbanism” which, from the remaking of downtown’s Olvera Street to Santa Monica’s Third Street Promenade to the La Brea Tar Pits, has always been a foundational if problematic component of the city’s public life.

Ulin touches on the influence of architects in the public realm – specifically, Eric Owen Moss’ privately funded Hayden Tract, “a once-derelict strip of industrial wasteland in Culver City that has become an open-air architecture showplace,” and Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Concert Hall which, while he finds its name “cringe-worthy...is a remarkably visible piece of public architecture,” that marks a change in how buildings actively welcome the passerby’s gaze. This is in stark contrast to LA’s architectural past, in which cultural hubs like the Los Angeles County Museum of Art “spent decades turning its back to the sidewalk.” While many of LA's public spaces have been commercially shaped into being, Ulin reflects on the notion that “what is a city, after all, if not a ‘scripted-space’—not in the sense of manipulation, exactly, but rather in the interplay of elements (architecture, density, the serendipity of the pedestrian) that create a three-dimensional environment?”

This script has its plot holes, of course. Ulin brings up The La Brea Woman, a skeleton reconstructed from a 10,000 year-old skull dredged from the La Brea Tar Pits and a modern woman’s tar-dyed bones, then made into a quasi-historical exhibit for visitors to the Tar Pits’ museum (which was removed from public view in 2004). The La Brea Woman becomes this weird emblem of Los Angeles’ urbanity: part artifice, part authentic, the city is built as much on real history as it is on what we wish our history to be. who, really, gets to say what our historic glory is?“What else is a city but an imaginatorium, where the surface, the public record, is constantly collapsing into the interior landscape, the streets as markers, territorial or otherwise, the building blocks, the triggers, of identity?” Ulin wonders. “That is how cities develop, that is how they evolve.”

Ulin closes the book with an anecdote about accompanying his grown son through the Theater District in downtown LA, where he reflects on the United Artists building, now operating as the Ace Hotel, which “not all that long ago used to be a church. Now it’s been restored to its historic glory—although who, really, gets to say what our historic glory is?”

the city is built as much on real history as it is on what we wish our history to beIntrigued by who, or what, will define the collective history of such a seemingly idiosyncratic place, I asked Ulin if we will have to edit Los Angeles down into a form we can collectively agree on, or if he thinks the city will always be able to maintain that one-to-one urbanity. After touching on the ideas about density in Michael Maltzan’s essay No More Play, Ulin replied, “My hope is that the city doesn’t become too generically urban as it continues to grow up as opposed to out. I hope what we would call the definitive LA component—which has to do with spectacle—remains part of who we are as well.” This sense of spectacle is most concisely illustrated in Ulin’s chapter on the Miracle Mile, in which he recounts the 2012 installation of Michael Heizer’s “Levitated Mass” sculpture, which required a 340-ton boulder be carted from Riverside via flatbed truck traveling approximately 10 miles per hour in the dead of night. The arrival of this rock, which was fixed above a below-grade walkway on LACMA's campus, prompted a slew of informal parties around the city – a kind of regional holiday.

Now that “Levitated Mass” is here, Ulin writes about the underwhelming experience of viewing it in situ, as if its primary artistic value resided in the spectacle of its journey. “Still,” Ulin writes of the rock, “if anticlimax is, perhaps, an inevitable response, it also part of the challenge of the piece.” Indeed: with Ulin as perspicacious guide, Sidewalking ultimately becomes a tour of the befuddling yet fascinating journey of Los Angeles itself.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.