Like an infrastructural Ouija board planchette, the Foucaultian “apparatus” isn’t exactly a device, but rather the effect of a multiplicity of participants. Each of these participants, whether they are the media, philosophical traditions, physical objects or even legal proceedings, exert a complex and nuanced force on the other, helping to control the method by which reality is shaped.

In “Imaginary Apparatus: New York City and Its Mediated Representation”, author McLain Clutter compellingly argues that the John Lindsay Administration in New York City (1966-1973)The planning documents begin to reflect the techniques of film, just as film begins to uphold the goals of the urban planner helped to construct an apparatus in which the forces of media and urban planning fed off each other to foster a new, more economically vibrant metropolis. What’s more, he posits that while “the relationship between mediated representations and cities is a well-trod area of inquiry,” studying an example of a mediating apparatus in depth can provide a kind of field guide for contemporary urban designers, regardless of their specific context. “The hope here is that by better understanding the mechanics through which urban reality is intermeshed with mediated representation, new tactics for operating on the city may be enabled.” Well, all righty.

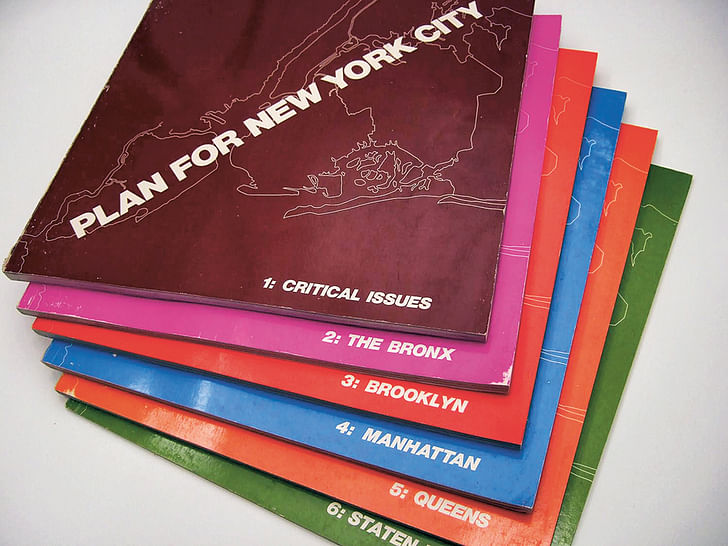

It’s a massive undertaking, and Clutter is wise to limit his scope in order to precisely articulate his points. He breaks the book into two major parts: “The Apparatus,” and “The City,” the latter of which is subdivided into three parts: Spectator, Desire, and Ecology. To flesh out the apparatus, he delves into the relationship between two media items: the 1969 Planning Commission’s “The Plan For New York City”, and the 1969 film based on that document, What is the City but the People? The latter charts the development and gentrification of swaths of midtown Manhattan through its soon-to-be-displaced inhabitants, while the former is a series of physical documents that describes the (then) current and proposed condition of each borough of New York City.

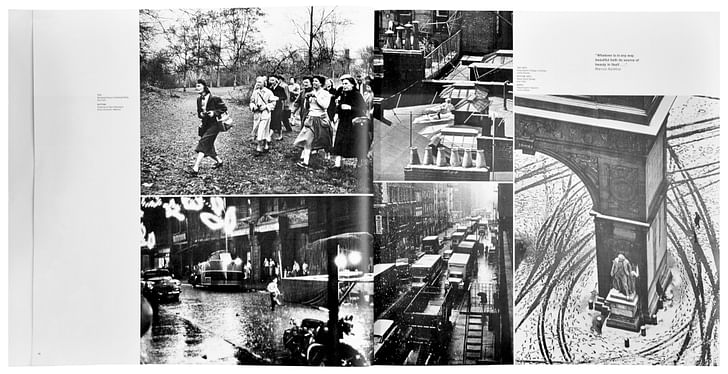

Part One liberally uses grainy stills from the film (which is included with the book as a separate DVD) to articulate the framing, context, and mediation of the physical environment. While Clutter freely admits that the film “is not a cinematic masterpiece,” his intricate analysis elevates it from mid-level infomercial into a surprisingly effective tool of influence. The notion of “grit” as a mediated urban component fascinates Clutter, and in his analysis What is the City but the People? purposefully focuses on capturing that cinematic patina.

In the film, abstract, aerial views of New York City are nixed in favor of broken-bottle fights between vagrants and grimy signage. The viewer begins to perceive the city as being burdened by a kind of restless violence, contained only by chance. The jump-cut style of the intro is displaced by smooth, relatively quiet tracking shots when urban planners are photographed walking around the previously jumpy urban neighborhoods. This pacing and framing is vital.

As Clutter explains, “Cinema has often been theorized as a representation of the consciousness of the urban subject. The registration of fast-paced events over time on film has been understood as an analogue to the registration of precisely those events – those stimuli – on the consciousness of the individual on the street.” A slower moving, more stately pace inherently signals to the viewer the mindset of the subjects being filmed.

Similarly, the choice of unidentifiable, essentially anonymous subjects within the photos included in “The Plan For New York City” is shaped by a desire to reframe the role of people within the urban environment: they are participants, but they are not the focus. The planning documents begin to reflect the techniques of film, just as film begins to uphold the goals of the urban planner.

Part Two’s “The City” is a far more wide-ranging and ambitious exploration of mediation on the metropolis, stretching outside the boundaries of the principal timeframe and touching on cinema from Midnight Cowboy to the work of Martin Scorsese. Each of the subdivisions of the essay, which are philosophically underpinned by the work of Guy Debord, Christine Boyer, and Walter Benjamin among others, explores a particular aspect of mediation on the physical environment of New York City, to different effects.

The “Ecology” subdivision is the most successful of all three components of Part Two because it integrates the major threads of the book in one tangible example. This example is the redevelopment The notion of "grit" as a mediated urban component fascinates Clutter of the theatre district in Times Square, which blends the comingling of public space, the desire for a kind of quasi-historic urban feeling, and the interconnection between city-wide economics, media, and urban planning. In a 17-block section, we have a brick-and-mortar demonstration of how the apparatus increased economic vitality by way of integrating visual ideas of urbanity propagated by media. Instead of cutting out the theater district and replacing it with office towers (ka-ching!), city planners and developers were influenced by the mediated notion of what the urbanity of New York should be and retained a version of its supposed historic self.

So how can urban planners attempting to design in the era of apps benefit from this book? Although it would be a leap to say that Clutter’s meticulous deconstruction of the relationship between official planning documents, cinema, and economic drivers serves as a kind of template of the governing forces within any large city development, the book does provide an excellent case study of the role of media within urban design. It’s safe to say that designers should not write off the effects of their particular dominant media form on the planning process; in a time in which our virtual lives can seem comparably important to our physical ones, we may start swiping left on our cities if we ignore the effects of our contemporary imaginary apparatus.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

1 Comment

I think the author is McLain Clutter, why it is Julia Ingalls?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.