This is the third installment of the recurring feature Architecture of the Anthropocene, which explores the implications of the Anthropocene thesis for architecture. The Anthropocene is a contested name for "the era of geological time during which human activity is considered to be the dominant influence on the environment, climate, and ecology of the earth."

Prior installments can be found here.

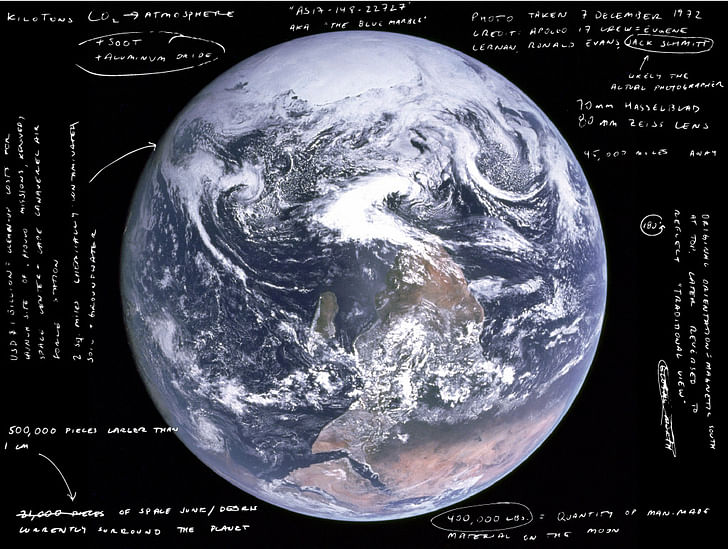

I. On December 7, 1972, inside a metal capsule hurtling towards the Moon, a man turned around and took a photograph. The lighting was perfect, the position of the Hasselblad camera was ideal: about 45,000 miles from the subject of the photograph, which loomed large but fit within the confines of the frame. A little while later, through the efforts of the writer and activist Stewart Brand, the image was released to the public. Dubbed “the Blue Marble” and likely the most widely-circulated image in history, the photograph is credited with spurring the emergence of the modern environmental movement and helping to create a “global consciousness.”In order to take an image of our home, the home itself was irrevocably changed But in order for the photograph to be taken, plumes of toxic chemicals were first forced into the ground beneath the launch site and, to this day, still require decades and billions to clean-up. For the camera to reach the necessary distance from the photographic subject, kilotons of carbon dioxide had to be jettisoned into the atmosphere. The propellants and fuel cells used to power the Saturn V rocket required large quantities of fossil fuels to manufacture, as did the rocket itself. Its engines emitted reactive gases that are probably still in the process of breaking down ozone in the atmosphere.

In order to take an image of our home, the home itself was irrevocably changed, in however minute and invisible a manner. Welcome to the Anthropocene.

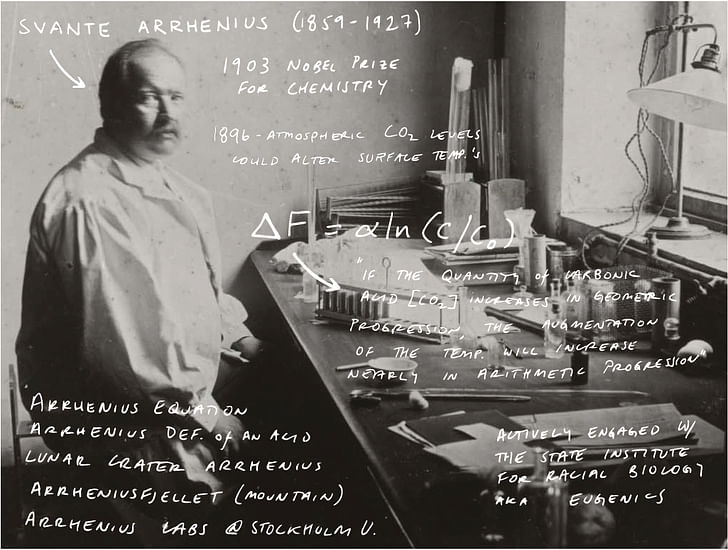

II. Despite popular imagining, climate change is nothing new. As early as 1896, the Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius predicted that “if the quantity of carbonic acid [CO2] increases in geometric progression, the augmentation of the temperature will increase nearly in arithmetic progression.” But it was only in the 1990s that computational modeling had developed to the point that a scientific consensus could be reached: the globe is warming, and humans are primarily responsible. Climate models were instrumental in making visible a phenomena that was already occurring, but they themselves are not climate change, per se. Global warming can be thought of as an object that is so massive in scale and temporality that it is invisible to the humans that reside within it, what the philosopher Timothy Morton calls a “hyper object." We cannot see global warming, but we can model a changing climate. We cannot see global warming, but we can model a changing climate We can see images of glaciers breaking off into the sea, storms destroying houses, crops withering in extreme heat. But these are not global warming, only its effects.

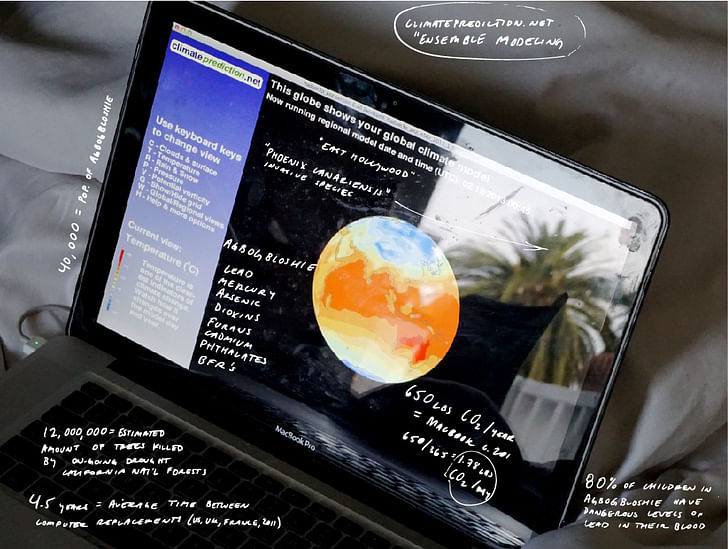

Recently, I downloaded a climate modelling software onto my laptop. Part of an Oxford-led program called climateprediction.net (CPDN), the models developed by my laptop are linked with those produced by thousands of other volunteer computers around the world “to answer important and difficult questions about how climate change is affecting our world now and how it will affect our world in the future.” Without distributed computing, climate modeling would otherwise require massive amounts of computational power. The models only run when my computer is idle and are not supposed to affect its normal usage. But my computer is over four years old and, like an abused pack mule, it creaks, it groans, and rainbows spin as I try to run Final Cut and Photoshop and Rhino all at the same time: I constantly worry that its end is near. So I deleted the software and my small quota of agential-feeling – albeit pathetic and minute anyway – went with it.

Inevitably, my laptop – and everyone else’s – will die, whether at the hand of built-in obsolescence or a spilled cup of coffee. Unless careful measures are taken, there is a chance that the metal and plastic clamshell form on which I’m currently typing will end up on the shores of Western Africa. Specifically, in Agbogbloshie, a suburb of Accra and former wetland that is now a massive e-waste dump allegedly in part built up of the waste of industrialized nations. Nicknamed “Sodom and Gomorrah,” Agbogbloshie serves as home for young boys who use foams to burn off the plastic of used electronics and, by hand, extract their interior parts. The population is primarily made up of migrants from Northern and rural Ghana. The map is not only an inadequate representation of the territory, but it also touches the territory and transforms it. They live, eat, sleep, and work in a toxic environment filled with poisons like lead, arsenic and mercury that also seep into the ground water. Inhabitants suffer from chronic health issues, particularly the children whose reproductive, nervous and neural systems are all affected.

Behind the scientific consensus that we call global warming, there is a history of infrastructural and computational developments that were fueled by burning the fossilized remains of ancient flora and fauna. Today, in order to model climate systems, massive computational power is required, enabled by equally massive amounts of energy, and the production of a good deal of e-waste. Compared to automobiles, manufacturing, building construction, the energy consumption and waste output is minimal, but it is still a facet of an aggregate system of human activity that is causing the planet to get warmer and warmer. The map is not only an inadequate representation of the territory, but it also touches the territory and transforms it.

III. I’m sitting in my apartment scrolling through a seemingly-endless stream of images of new buildings, architecture renders – what’s sometimes called called ‘design porn.’ I have a tab open to an article titled “Your Porn is Watching You,” about the unique, identifying “footprints” or “fingerprints” you leave “all over the webpages you visit.” I’m reading my friend a draft of the article that you’re currently reading, and I tell her that I’m worried about an apparent schizophrenia in my thinking: in a singular moment I can simultaneously experience immense excitement over tech advances and innovative design, and feel an overwhelming fatalism about the future. I think about the digital footprints I’m leaving on architecture blogs and about the carbon footprints I’m leaving all around me. I think about the LED lights above us and the wifi signals encircling us, Where does the work of architecture begin and end? not to mention the entirety of small little events in my life and her life and the house’s life that all came together to produce this singular, absolutely banal moment. I scratch my head.

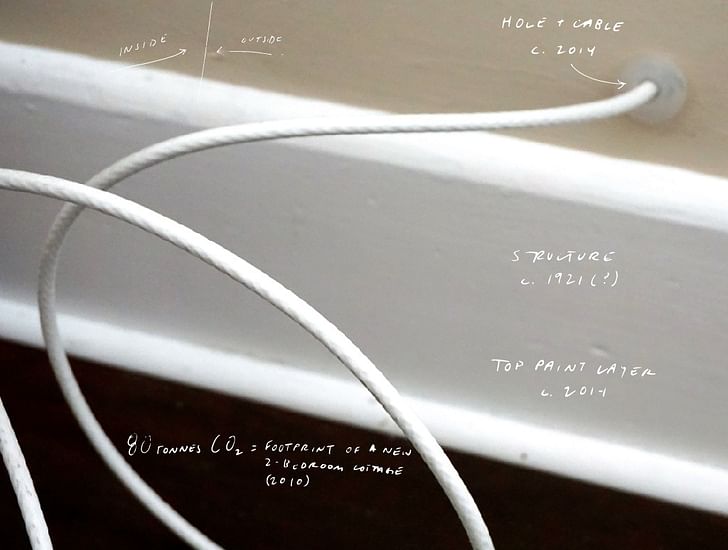

Almost exactly a year previously, while sitting on the same couch, I made a call to the cable company because I couldn’t find the cable jack to setup the wifi. It turned out there was none and I had to have the cable company drill a small hole from the outside of the building into one of the rooms. The history of my home has never been written. I have no idea when wires were put in, ripped out, or replaced in the walls, nor do I know the origins of the ghosts behind the strangely placed deadbolts or the sealed-up door in one of the bathrooms. But it felt strange, in 2014, to have to physically bore a hole into a wall so that I’d be able to sit on What is the position of a singular building within its context?my bed and scroll through backlit images of a museum that may never be built in a Scandinavian city that is trying to make its ‘center’ carbon-neutral by the end of this year.

Where does the work of architecture begin and end? Is there some essence of my apartment that connects its construction to the hole bored into its plaster by a contractor for Time Warner Cable in 2014? What is the position of a singular building within its context? Does it include the carbon emissions released by a truck almost a hundred years ago when it brought pulverized rock from some nameless quarry to the plot of ground that I’m now suspended above, sitting at a table, typing and sweating because today is the hottest on record and my apartment doesn’t have air conditioning?

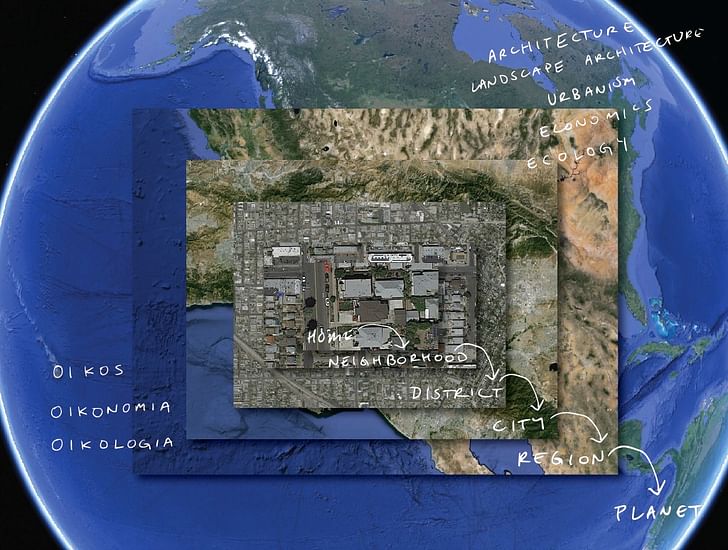

IV. Architecture is a bit like a Matryoshka doll. The smallest unit is the individual home, then there’s the property boundary, the block or neighborhood, the city – proper then periphery, then the county, the nation, the world, etc. Such a model for architecture practice could be articulated in different ways, through the various professional or academic adjectives, like landscape or urban, that suffuse architectural discourse. Regardless, architecture – which is commonly conceived of as the delineation of an interior against an exterior (and the division of the interior into smaller spaces) – is always inside of something else. And its form correlates to the objects that envelop it. Perhaps most of all, architecture is inside of architecture. Perhaps most of all, architecture is inside of architectureArchitecture comes to us with an a priori set of conditions, a concatenation of historical thinking and building that prefigures and often preempts our potential moves.

It’s not a coincidence that a practice mostly dedicated to the use of walls to separate spaces is constantly marking boundaries on its own body, to either define or excuse itself. For example, someone claims that architecture is that which is built by licensed practitioner not the developer, or by a well-known architect rather than the one designing that condo, or as the set of buildings built during that time period rather than the other one. But every attempt to assert the autonomy of architecture belies a fundamentally contingent relationship – specifically, to an “other” architecture. In order for there to be a “high” architecture, there must be a mass – a majority – of banal (albeit by definition thriving) architecture. A historically-significant building needs to be buttressed by apparently “non-historical” buildings. When an architect claims the ecological issues are outside his purview, economic requisites are almost always brought in as a defense. Seemingly everyday, more and more walls are erected within architecture: between those who respond first and foremost to the client, or to policy, or to ecology, or to play, or to form, or to experiment, or to style, or to landscape, or to the everyday.

While architecture – the word – can signify a profession, a building, a class of buildings, or the expanded field of the built environment, the manner in which whatever architecture contributes to or exacerbates conditions of global warming has implications for every other sense of the word. In reality, no walls are actually impermeable – either architectonically or conceptually. Hasn’t architecture, at its best, always been the practice of translating the impossible into reality?There is no ontological border between my home and the economic and ecologic systems that determine the conditions of my living in it.*

Architecture is always an ecological, political, social and ecological practice: the Anthropocene thesis brings this idea into focus. Never has the need been greater, or the stakes higher, for individuals and groups who can somehow keep in mind all these varied, and often apparently divergent, imperatives. We need architects who can respond to clients without destroying the planet, who can work against social inequities while also creating livable cities. We need every architect to become a landscape architect – but without imaginary boundaries for a site. This is an impossible task, no doubt – but hasn’t architecture, at its best, always been the practice of translating the impossible into reality?

*It is worth noting here the common etymological root of ecology and economy is oikos. Oikonomia, or the management of the home, is as much, if not more, a determining factor in its form as any designer. Likewise, as is illustrated in section II, even the “study of the house,” or oikologia, ends up touching it and affecting it.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.