If the job’s done right, the architecture will outlast the architect. But when building for the present and unknowable future, the past is the only reliable hint at what may come next. Future Anterior is here towards that end, to critique and analyze architectural historic preservation.

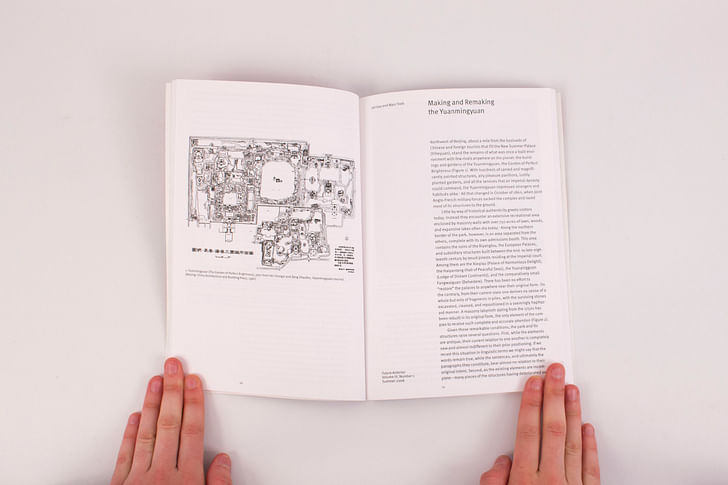

Published twice yearly by the University of Minnesota Press, Future Anterior is the first American academic journal for historic preservation, having published its first issue in 2005. Concerned both with what has not yet happened (future) and what has already happened (anterior), the journal connects the temporal and conceptual fields of preserved and anticipated architectures.

For Screen/Print, we’re featuring a piece by the publication’s founder and editor at Columbia University’s GSAPP, Jorge Otero-Pailos. Entitled “Creative Agents”, the piece gives credence to preservationists’ role in creating and framing new architecture, challenging the authority of the building’s architect. It was originally published in Vol. 3, Issue 1 of Future Anterior in Summer 2006.

>Otero-Pailos is an architect, artist, and associate professor of historic preservation at the GSAPP.

The wrecking of a building is already a spectacle, although not one supported by any dramatic intent. The collapsing roof of a burning building, the toppling of a dynamited chimney stack are thrilling moments, even if we feel a little shame for admitting the fact. [...] Could we design our buildings to wreck well –that is, not only to be easy to destroy but spectacular as well? (What a peculiar idea!) There could be a visible event and a suitable transformation when a place “came of age” or was about to disappear.

-Kevin Lynch, What Time is This Place?, (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The MIT Press, 1972), 178.

historic preservationists challenge the presumed monopoly of the “architect-author” over architecture

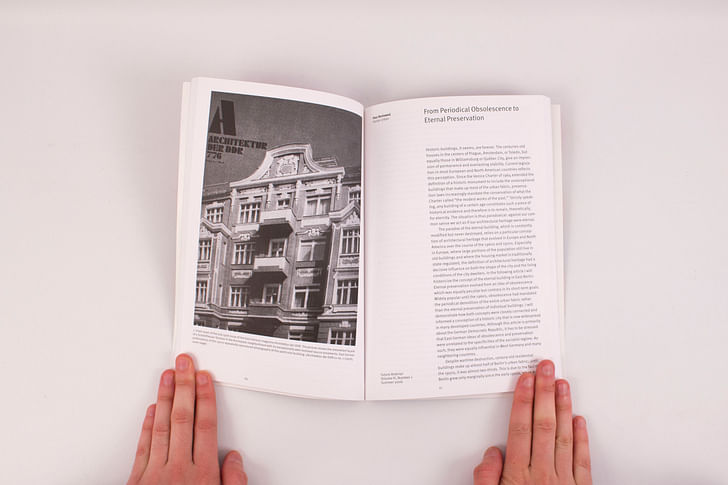

The idea of designing the “endings” of buildings is an important contribution of historic preservation to architecture, as the latter has previously only been concerned with the design of opening sequences, to use a filmic analogy. By aestheticizing the endings of buildings historic preservation fundamentally transforms them. And so, historic preservation is burdened with having to justify its intent. For what purposes do we intervene? Insofar as aestheticizing endings is a way of protracting them, the practice is often referred to as “saving” the building. But “saving” a building is never a disinterested act. One can save a building in the interest of say culture, or economy. What does it mean to “save” it in the interest of architecture? In that case, the purpose of our intervention is primarily to reveal something about architecture that could not be disclosed other than through our involvement in that particular building. Now architects and architecture historians typically assume that the historic preservationist intervenes in order to reveal the architecture that was already in the building –deposited there presumably by an Architect. But if we examine closely the aesthetic practices of historic preservationists we will find that they often disclose architectural dimensions of buildings that were unintended by its “original” architects. Seen in this way, historic preservationists challenge the presumed monopoly of the “architect-author” over architecture, and require a new model for understanding how various “creative agents,” as I propose to call them, involve themselves in the advancement of architecture through the transformation of buildings.

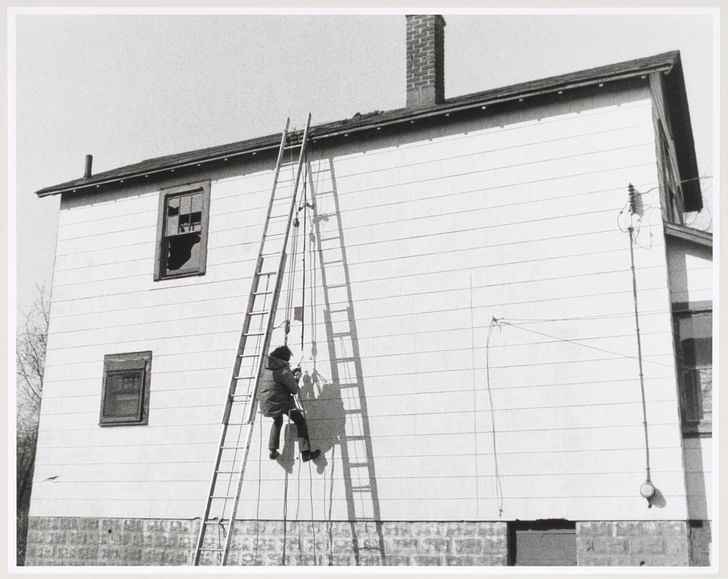

Through Matta-Clark’s intervention this building surged into architecture long after it had been erected.

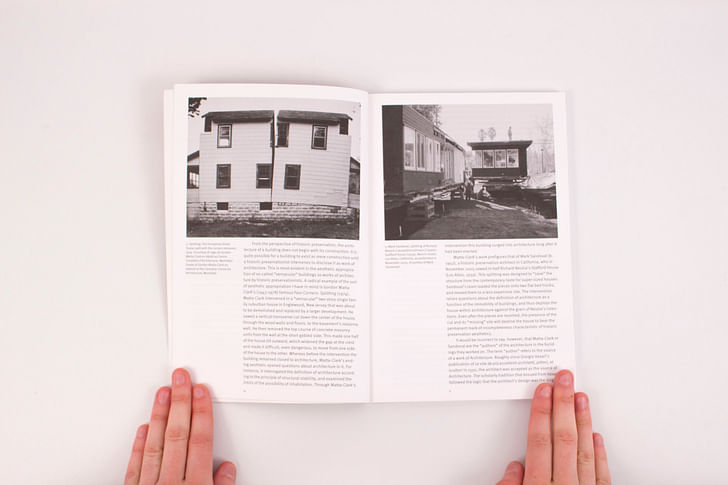

From the perspective of historic preservation, the architecture of a building does not begin with its construction. It is quite possible for a building to exist as mere construction until a historic preservationist intervenes to disclose it as work of architecture. This is most evident in the aesthetic appropriation of so-called “vernacular” buildings as works of architecture by historic preservationists. A radical example of the sort of aesthetic appropriation I have in mind is Gordon Matta-Clark’s (1943-1978) famous Four Corners: Splitting (1974). Matta-Clark intervened in a “vernacular” two story single family suburban house in Englewood, New Jersey that was about to be demolished and replaced by a larger development. He sawed a vertical transverse cut down the center of the house, through the wood walls and floors, to the basement’s masonry wall. He then removed the top course of concrete masonry units from the wall at the short gabled side. This made one half of the house tilt outward, which widened the gap at the crest and made it difficult, even dangerous, to move from one side of the house to the other. Whereas before the intervention the building remained closed to architecture, Matta-Clark’s ending aesthetic opened questions about architecture in it. For instance, it interrogated the definition of architecture according to the principle of structural stability, and examined the limits of the possibility of inhabitation. Through Matta-Clark’s intervention this building surged into architecture long after it had been erected.

Matta-Clark’s work prefigures that of Mark Sandoval (b. 1952), a historic preservation architect in California, who in November 2005 sawed in half Richard Neutra’s Stafford House (Los Altos, 1939). This splitting was designed to “save” the structure from the contemporary taste for super-sized houses. Sandoval’s team loaded the pieces onto two flat bed trucks, and moved them to a less expensive site. The intervention raises questions about the definition of architecture as a function of the immobility of buildings, and thus deploys the house within architecture against the grain of Neutra’s intentions. Even after the pieces are re-united, the presence of the cut and its “missing” site will destine the house to bear the permanent mark of incompleteness characteristic of historic preservation aesthetics.

It would be incorrect to say, however, that Matta-Clark or Sandoval are the “authors” of the architecture in the buildings they worked on. The term “author” refers to the source of a work of Architecture. Roughly since Giorgio Vasari’s publication of Le vite de più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori in 1550, the architect was accepted as the source of Architecture. The scholarly tradition that ensued from Vasari followed the logic that the architect’s design was the single source of Architecture. In this model the building always stood as a more or less “deficient” execution of the “ideal” design. This tradition came to a head in the 1960s with the architectural reception of structuralism. Roland Barthes’ “The Death of the Author” (1967) and Michel Foucault’s “What is an Author” (1969) prompted studies that questioned previous assumptions by focusing on the process of how individuals come to be considered authors. For an architect to be recognized as the author of the architecture in a building he had to undergo a process of “authentication” by various institutional mechanisms such as professional associations, government agencies, architectural journals, architecture critics, and historians. Questions arose about the vested interest of these institutions in shoring up what by then appeared to be the “mythology” of authorship. Contemporary historic preservation emerged in this intellectual context, in opposition to the reduction of architecture to the “authority” of the architect, as a means for various creative agents (such as “the public”), who had been relegated to the margins by the mythology of authorship, to lay claim to architecture and participate in the struggle to define it.

historic preservationists aestheticize the many endings of buildings

The architectural adaptation of the 1960s critiques of authorship had the positive effect of recognizing that architecture is a discipline; that is to say a social and institutional intellectual formation which is not identical to buildings. But it had the negative effect of assuming that therefore physical buildings were secondary or even unessential to architecture. The resulting discourse was an anachronistic throwback to Vasari, which gave primacy to the economy of architect-produced images, over the “defective” building, and thus the import of the critique of authorship only reinforced the myth of authorship it purported to take down. The unexamined premise of this dismissal was that existing buildings could not contribute anything new to the advancement of the architecture discipline after the involvement of the “original architect.” But as the work of Matta-Clark and Sandoval demonstrates, existing buildings can further architecture even in the absence of an “original architect.”

Because historic preservationists aestheticize the many endings of buildings, their aesthetic production is free from the myth of single origins (and originality) that governs current thinking about design. They cannot presume their designs to be the authorial “source” from which architecture’s disciplinary body of intellectual, aesthetic, and practical knowledge emanates. Historic preservation destabilizes the belief that design is the ex-nihilo “origin” of architecture, undercuts the hegemonic figure of the “architect-author,” and signals the legitimacy of other “creative agents” (understood as an individual or a collective). From the perspective of historic preservation, design appears as a “response” to given material and intellectual conditions that furthers the creative agent’s interests in a field. Creative agents advance their interests in architecture through designed interventions in existing buildings, which challenge architectural conventions, and weaken its disciplinary boundaries. Understood in this way, design is not architecture but the art of transforming its relationship to this building at this particular time. In other words, design is an appropriation of buildings into works of architecture. But buildings are material entities. They come to be and inevitably cease to exist. And so design can only appropriate them into works of architecture temporarily. As such, design is an “event” of appropriation.

We can now add nuance to our response to the fundamental question of historic preservation: What does it mean for a creative agent to “save” (or design the ending aesthetics of) a building in the interest of architecture? It means to create events of appropriation; to design moments for appreciating the manner in which architecture and buildings become mutually contingent; to create opportunities to witness how the upsurge of buildings into architecture, and of architecture in and through buildings, stamps both of them in time, and renders them historic. This is the sense in which the term “historic” enters preservation: as the incomplete, contingent, and temporal way that architecture and buildings differ from one another, while constituting each other. The historic destabilizes the association of preservation with permanence, undercuts the presumed identity of buildings and architecture, and undermines the primacy of the “original author” or the “original design” as the centering reference of architecture. Through the aesthetization of the historic, creative agents lay claim to buildings and architecture from the margins, redrawing the contours of the discipline towards a non-foundational design practice.

Also featured in Vol. 3, Issue 1 of Future Anterior:

Click here to read the rest of the issue, or peruse other editions of Future Anterior.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured Future Anterior.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

2 Comments

^ great article, quite relevant to some of the discussions here lately.

It brings up the interesting idea that historic preservation is an act of design - which immediately seems obvious - but I hadn't quite thought of in that way before.

What I like is the recognition that Architecture isn't some fixed meaning handed down from the Architect in a perfect state - it's a quality that develops and changes and sometimes disappears from buildings and places according to the culture around them. The concept offers some salvation from the intellectual monopoly of starchitecture in that we can envision cutting up and re-appropriating built works to suit our own manner of appreciating them, and recognize that doing so is a form of preservation much more relevant than embalming them in an unusable original state.

I also like the challenge to the idea that an original design is the fixed story of a building. This seems like a relatively new phenomenon where by the "truth" of a building's history became more important than its present place in culture. One can look at Williamsburg's preservation as an example where 200 years of history where stripped off to create an imagined version of its colonial past, thus embalming it. The other side of this coin might be due to the ever increasing speed and kind of change in the modern world. With mass industrialization in the late 19th century, the speed of re-building in cities increased to an unprecedented level and as such destabliized people's conception of place and identity. While I like appreciate the accumilation of history in buildings, I can also see why some would like to "freeze" history becasue of both the speed of change and the discontinuity imposed by the modernist aesthetic which sought a stark break from the past. This was an intended consequense of the "end of history" idea where it was sealed off in a supposedly "nostalgic" past, inaccessible but through a conservationist's gloves. So while I agree with the premis that buildings aren't or shouldn't be frozen in time, I also understand people's apprehension with change when it's often seen to be antithetical to those very qualities they love about older places and buildings.

What I found fascinating is the bifurcation of a building from its 'architecture' as if anyone can presume to differentiate "mere construction" from a "work of architecture". While I agree that some structures are clearly "mere construction", it seems a fools errand when there is so much grey area and becasue it prejudices one's view of what can never be known unless one has been in the mind of it's creator. When does a building become a work of archtiecture is a parlor game that says more about the author than a building.

We have to remember that most people don't consult with "professional associations, government agencies, architectural journals, architecture critics, and historians" to "authenticize" buildings. The fact that Vasari proclaimed an architect's monopoly on authorship or the primacy of it's design has never mattered for those who live in and among our historic districts. For them, a building's accumulation of history memory is as much a part of a building's design as its original design. One thinks of Henry Hobson Richardson who would tear down parts of a building while going up if the drawn design proved unsatisfactory. Granted, today this happens for less altruistic reasons, we should beware of bestowing too much importance on historical proclimations, expecially since their actual context is difficult to fully comprehend.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.