Western civilization has never been particularly adept at dealing with death, which is perhaps why its own eventual collapse is such a source of cinematic fascination.

Movies about the apocalypse, whether they are prompted by the supernatural or the probable, function as a kind of cultural anxiety release valve. We watch the end of the world and then leave the theatre or turn off our screen, still triumphantly breathing. While the End of the World is hardly a new dramatic topic for cinema (See: 1916's Danish-made The End of the World), in the last few decades the sheer number and variety of approaches to the final adios has become its own genre, spanning the full spectrum from excellence to also-rans.

So, to paraphrase Humphrey Bogart, if The Maltese Falcon (1941) is the stuff dreams are made of, then just what is the material of the apocalypse? Unsurprisingly, it derives from the building blocks of civilization itself.

1. The Major Types of Apocalypse: Hyperrealism and Realism

Before diving into apocalyptic cinema's material ending, it's worthwhile to discuss its basic forms. Although each film manifests devastation in its own particular way, apocalyptic cinema breaks down into two major types: The Hyperreal/Supernatural variety, and gloomy Realism. Demons, superhuman trips around cosmic bodies, Gods with time on their incorporeal hands: these are the basic world-enders of Hyperrealistic apocalyptic cinema. Alternatively, plagues, natural disasters, and weaponized nutcases destroy it in the category of Realism. Regardless of the type, swelling organ music seems to keep everybody alert.

Demons, superhuman trips around cosmic bodies, Gods with time on their incorporeal hands: these are the basic world-enders of Hyperrealistic apocalyptic cinema.In the case of Hyperrealism, the materials that constitute the apocalypse are usually portals suspended mid-air that are seemingly plasma-based. This is true in Ghostbusters (1984), with its writhing keymasters and gatekeepers and slimy demon dogs, and also for the majority of season-ending apocalypses on Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003), which surely have garnered the protagonist some Frequent Portal miles by now. Apocalyptic space epics, such as Interstellar (2014), favor similar constructs. Interstellar benefits from our paucity of understanding of quantum physics to shuttle Matthew McConaughey through a wormhole suspended just around the block from Saturn – a gravity-bending portal that ultimately leads him to confront life, love, and everything. (Spoiler: he later dives into a black hole, where he encounters a tesseract that displays time as a solid dimension, a trippy concept that allows him to hover near every discrete moment of a bedroom back on Earth. In its execution, it's reminiscent of visiting an IKEA on freakish repeat.) McConaughey avoids the apocalypse-solving crutch of Superman (1978) where Christopher Reeve does a few wheelies around the sun to reverse the flow of time and a subsequent nuclear apocalypse. He also doesn't take the tack of the hero in The Quiet Earth (1985), who roams around a mysteriously abandoned earth looting and weeping and exulting until he eventually wakes up somewhere that has a killer view of Saturn.

Realistic apocalyptic cinema, on the other hand, usually sticks to the abandoned car-flooded streets and downed electrical wires we're used to. Dust cakes everything, and monosyllabic pronouncements are du jour, as are eerie swaths of silence. Consider Steven Soderbergh's Contagion (2011), the freaky, blood-jetting-from-jetsetters template many assumed the real life Ebola epidemic would resemble. Soderbergh spends a great deal of time isolating and then framing his characters in quiet, floor-to-ceiling window-laden rooms, underscoring how trapped they are by the invisible force field of fear. That many of them get sick and die is secondary; panic is the disease that's really going viral.

Realistic apocalypses also can be more personal, or chart the end of a particular culture or region, lending them greater pathos. Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012), although it does eventually include elements of fantasy, starts out as a stark portrayal of climate change – the unsexy, slow apocalypse we're all living through in real life now. This is a particularly wrenching film because of how ably it not only charts the end of what appears to be southern Louisiana, but also the unthinking prosperity of the American Middle Class. Materially speaking, Beasts tells this story by setting the action in poorly constructed shacks made from found, dinged-up refuse from the former age. Although slivers of the still-going outer world peek through, the film’s child protagonist is destined to be the last generation of a once-flourishing culture, as, perhaps, will many of its contemporary viewers.

1.A: Notable Sub-Genres of Hyperrealism and Realism

The 1990s witnessed a slew of apocalyptic-themed cinema that, oddly enough, almost made the actor Keanu Reeves a kind of sub-genre all on his own. Whether he was monosyllabically diving onto buses (Speed, 1994) or encouraging bullets to slow down and take a break (The Matrix, 1999), Keanu seemed to be everybody's go-to guy for keeping the world as we know it panic is the disease that's really going viral.intact. Keanu skipped ably between Hyperrealism and Realism, at a later point showing up to combat demons and rogue angels (Constantine, 2005). What's intriguing about Keanu and the archetype his roles represent is the idea of the lone man confronting the great challenge. Although The Matrix is arguably an ensemble piece, "Neo" is its leader, notwithstanding Laurence Fishburne's as yet unmatched expository coolness. This single leader fixation is a little misguided: despite having had multiple lessons about absolute power corrupting absolutely (See: Julius Caesar, B.C. 40, Hitler, 1944, Osama Bin Laden, 2001, etc.) Western civilization’s media is still jonesing for that one man to take us away from our problems, a kind of heroic Calgon who leaps in and freshens everything up.

However, Keanu doesn't have a lock-down on the archetypal savior figure. Buffy the Vampire Slayer is also a notable and intriguing entry as a sub-genre in the Hyperrealism category. As a protagonist, Buffy is the female, high-school version of the archetypal single leader, although much like Neo in The Matrix, she has an entourage to back her up. She slaughters various gooey/creepy/unpleasant things, mainly at night. Buffy's quip-heavy stroll through a dozen or so world-endings is less about exhibiting her individual strength than the under-documented strength and intelligence of women in general, a sadly radical concept on which Joss Whedon built a career.

The series is primarily an extended metaphor for adolescence, but within that framework it manages to explore all sorts of horrible emotional apocalypses: the end of trust in institutions (Season 3 & 4), the end of childhood and the acceptance of responsibility towards others apocalyptic cinema invariably contains a key sequence framed within columns.(Season 5), the realization that some of your most beloved are probably going to lose it at some point and possibly threaten your life with their behavior (Season 6), and finally, the loss of one's singular identity, and the move towards identifying oneself via a community of genuine peers (Season 7). In Season 5, Buffy gains a sister but loses her mother, while in Season 6, she gains a peroxide-blonde undead lover but nearly loses her best friend from childhood to the thinly veiled forces of addiction and unchecked rage. Although each of these transformations is delivered via a supernatural or magical conduit, almost twenty years later Buffy is still one of the most honest portrayals of adolescent and young adult emotions. From a material perspective, Buffy usually ends up duking it out with some form of steel, whether it's a galvanized platform (Season 5) or a shiny weapon engendered with unnaturally powerful forces (Season 7).

However, regardless of the type of apocalyptic cinema, on closer analysis all of these films and TV series tend to favor the same architectural material to bring the house down: columns.

2. Materiality: Columns

Oddly enough, columns – usually, but not exclusively, made of concrete –unifies all of these disparate world-endings. As a kind of salute to the classic Greek and Roman building element from which Western Civilization sprang, apocalyptic cinema invariably contains a key sequence framed within columns. Perhaps the ode goes farther back, to the architectural one-liner of Stonehenge, which with its massive stone tablets forms the crudest possible version of what would later become the stately, refined columns of ancient Greece and Rome.

Perhaps columns figure so heavily in the end of the world because they are a definitive mark of humanity. After all, natural ecologies do not arrange themselves in neat rows. This is reflected in Lars Von Trier's Melancholia (2011), where a young jilted bride suffering from depression ends up being the only member of her wealthy family able to fully comprehend the reality of a massive planet called Melancholia en route to obliterate the earth. After a prolonged intro showing us the eventual destruction of Earth as seen from space, the viewer sees two parallel lines of hedges framing the ominous, multiple-planet laden sky. It is almost as if we are being given a clear throughline of the peak of civilization and its soon-to-be extinction; an elaborate sundial holds the foreground, graduating us into the ordered, manicured rows of shrubbery which point us to the chaos of planetary bodies gone rogue. Later in the film, as Keifer Sutherland's small family takes in the looming threat of planet Melancholia through a telescope, they do so against a backdrop of granite/concrete columns. Finally, as the women and children prepare for the imminent crash of Melancholia against Earth, they take shelter on the far end of the lawn under a strung-together arrangement of branches and sticks, a kind of collapsed columnar wood tent.

The Matrix also uses columns as a symbol of destruction and death. In the first installment of the trilogy, Neo and Trinity enter a highly secured building that features a series of columns within its lobby. It is here that the two discharge an impressive amount of ammo into the columns and the surrounding security guards while executing 360 degree flips and turns. The manicured rows of shrubbery which point us to the chaos of planetary bodies gone rogue.slow motion elegance of this sequence, combined with its high body count and unmitigated attack on the otherwise inert architectural materials of the interior, is one of the most watchable shoot-ups ever. It helps, of course, that the humans getting gunned down aren't really "humans" at all, but computer constructs designed by a machine intelligence that is not besotted with free-thinkers. Essentially, Neo and Trinity are trying to destroy the architecture of a false world, which in the mythology of the films is the world that the audience inhabits. It's a kind of upbeat apocalypse against the tyranny of conformity and unquestioning allegiance, but whether they're made of green streaking numbers or granite, columns still represent the ultimate form of civilization. If you want to destroy a world, you need to blow up its supporting columns first.

Meanwhile, season 3 of Buffy the Vampire Slayer finds Buffy and the Scoobies doing battle with "The Mayor," a supernatural being who is trying to transform himself from a small city government servant into a massive snake-demon hybrid, a political ambition that is served in about as thin a wrapper of metaphor as one can make. The Mayor's transformation takes place at the local high school, which features an exterior adobe corridor supported by columns. The Mayor shoots through this corridor at precisely the moment that Buffy et al detonate bombs, thus exploding the mayor, the school, and any attempts he may have harbored to dominate the world at large. In this sense, Buffy destroys a world within a world. While her actions have averted the apocalypse of the larger globe, she has ended the existence of a particular society and culture.

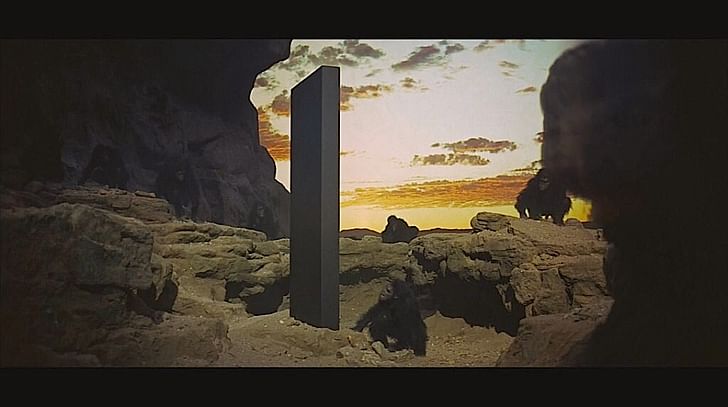

Of course, the most blatant and visually resonant example of the column as civilization-signifier and world-ender occurs in Stanley Kubrick's 2001. Again and again, whether it's a spaceship or a tossed bone from a hammy ape, we are confronted with this symbolic shorthand for civilization. Like most of Kubrick's canon, 2001 has held up over time because it artfully explores terror and alienation, emotions that never go out of style. It wouldn't be too far of a stretch to say that thanks to 2001, the power of the column-as-symbol of civilization has become permanently embedded within the larger cinematic universe.

3. Collapse

There is one movie in particular that serves as the best, and arguably most powerful, contemporary apocalyptic film of them all. Fight Club (1999), based on the 1996 book by Chuck Palahniuk and directed by David Fincher, was released at a time when the Western world's greatest fear revolved around the "Y2K disaster," a theorized possibility that a kind of upbeat apocalypse against the tyranny of conformity and unquestioning allegiance computers might crash everywhere when the year 2000 hit. Although sporadic incidents of single-cell terrorism had been sparking intermittently over the past decade (World Trade Center bombings 1993, Oklahoma City 1995, protracted unrest throughout the last few decades in Gaza and Beuirut) the West and the United States in particular held a kind of guarded stance towards the actual possibility that any of this would matter on a meaningful scale. Isolated incidents were just that, quelled with specially trained SWAT teams and surgical strike missions. Francis Fukuyama, after all, had declared "an end to history" after the Berlin Wall fell in 1989; the Cold War was over, and a new age of peace had (supposedly) begun.

Fight Club is subversive and raw and, in 2014, now seems like a weirdly prophetic postcard from the past. The movie charts the development of an underground radical group led by Edward Norton, intent on blowing up the staid, boring, soul-crushing reality of consumerist capitalism. Norton's character, who for various spoiler-necessitating reasons remains unnamed for the duration of the film, notes from the vantage point of his boring job and pop culture lifestyle that "This is your life and it's ending one minute at a time." It's the postmodern update of T.S. Eliot's observation that he's measuring out his lifetime in coffee spoons, but Norton is not content to simply poetically observe. He finds himself drawn to the charismatic and seemingly fearless Brad Pitt, who encourages Norton to steal and fight and otherwise beat the numbness out of his life. As the two continue to hang out, Norton gets drawn deeper into a weird realm of destruction and violence and unchecked rage. He's uncomfortable with this, but he also finds he can't exactly go back to his lifeless life. The actions he has taken have awakened him to a degree and level that makes inhabiting the narrow constraints of his previous existence impossible.

Much like The Matrix, Fight Club upon its release was less about glorifying violence than it was about not buying into conformity and investing your own life with actual meaning, whatever form that took. It was a celebration of passion, and also a meditation on what happens when passion is left completely unchecked. However, when viewed in our current context, it feels like a valentine to an era which most people in the 21st century find sweetly If you want to destroy a world, you need to blow up its supporting columns first.quaint. In the world of Fight Club, as in the last decades of the 20th century, getting a "job" is treated like getting a coffee; you could do it pretty much anywhere, and it was fairly unremarkable. Contrast this with today's economy and culture in which well-paying work is predicated largely on highly specialized skill sets, and "jobs" that do not require these skills can pay the kind of wage that officially places full-time workers at or under the poverty line. Walmart, the largest private employer in the U.S., pays its Sales Associates an average wage of $8.81/hour in 2014. While the economy has become globalized, leading to a class of freelancers and multi-national corporations, it would be fair to say that Americans' relationship to work has changed. Unfortunately, those who do go to school to acquire specialized skills also manage to rack up a lifetime load of debt. "Entry-level" seems to have been replaced by "internships," and people can now expect to change jobs at least half a dozen times in their lifetime. The idea that Norton's average Joe with no particular brilliance could afford a large apartment and the agonized boredom that drives him to acquire material possessions he would later learn to resent seems fantastical, and yet it was a reality then. Edward Norton's character, in other words, was massively relatable.

In September of 2001, a group of extremists flew planes into the World Trade Center in New York City, a pair of orthogonal office towers designed by Minoru Yamasaki that very much resembled columns. The act was couched in hate-fueled symbolism; by taking down one of the economic centers of what was increasingly becoming a global economy, a small group of very backwards types were declaring war on an entire way of being, a civilization they whether it's a spaceship or a tossed bone from a hammy ape, we are confronted with this symbolic shorthand for civilization.despised and wished to end. While the extremists targeted multiple other sites within the United States, the crumbling Twin Towers have become our visual representation of this particular moment in time when a noun, "terrorism," unfortunately became a national existential era, replete with its own uninspiring fear swatches of orange and red.

This is why Fight Club is inadvertently one of the most visceral and spot-on apocalyptic films, at least for Western civilization, and U.S. citizens of a particular age. The conclusion of the film finds Edward Norton and Helena Bonham Carter in a darkened office tower in an unnamed city. Edward Norton has shot himself, at last killing off the self-destructive side of his personality. He and Helena stand together in front of a vista of other rectangular quasi-Miesian office towers, which taken in a group form a kind of massive series of columns. As Norton proclaims that Helena met him at a strange point in his life, the radical group’s crowning, elaborate, multi-city plans abruptly begin, detonating the cityscape in front of them. Tower after column-like tower crumbles into dust as an entire civilization dominoes to an end.

Although this destruction involves only explosives and no planes, the scene now seems less like a staged fiction and more like a stylized documentation of the end of a particular era. This strange, numb world of Norton's is sealed in history, a time capsule of what seems like a bizarrely self-absorbed lifestyle and national outlook. As The Pixies' "Where is My Mind?" plays over Fight Club's credits, we are able to exit the theatre intact, out of one column-free reality and into another.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

4 Comments

Apocalypse is also made of media hype/fear tactics, which is what kept architects from realizing what we all instinctively knew. All one must do is look at the way Minoru Yamasaki's other famously demolished building, Pruitt-Igoe, came down in order to see what really happened to the WTC towers. For me, 7 World Trade Center remains the most haunting example of who these extremists really are. Could terrorists have accomplished the clearly planned demolition of all 3 towers that came down that day? I don't think so. The apocalypse already happened on 9/11/2001.

gbaker, no room for outdated popular paranoia here. Take your idiotic conspiracies back into your deep cave of ignorance.

for those who didn't get the reference (such as myself) "a kind of heroic Calgon" see this link

Wow, seriously packed full of intense layers here, like t.s. Eliot poetry.....everyone should have a Fight Club experience, it's good for you....the soul-crushing comment and mind numbing job reminded me of this. http://www.whysanity.net/monos/trainspot.html the last 2 or 3 paragraphs here, starting with the one discussing walmart pay, begs the question - what is their to choose? ...also lots of quotable stuff here and elsewhere in your writing.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.