What is the line between sanity and insanity? Specifically, what is the material?

Fictional universes are not merely the province of entertainment, but rather the country of our unsettled emotions. We'd much rather watch an actor struggle with his moral code than wrestle with our own. To aid in this vicarious reckoning, the emotional element of any worthwhile film or series is often subtly embodied in tangible materials. We see a certain kind of pocketed, acoustic wall paneling, for example, and we understand that we have The boundary between right and wrong is not only porous, but actively sucking us into the void.entered a nebulous zone between safety and danger. The darkened openings, the seemingly chaotic pattern of the holes themselves: The boundary between right and wrong is not only porous, but actively sucking us into the void.

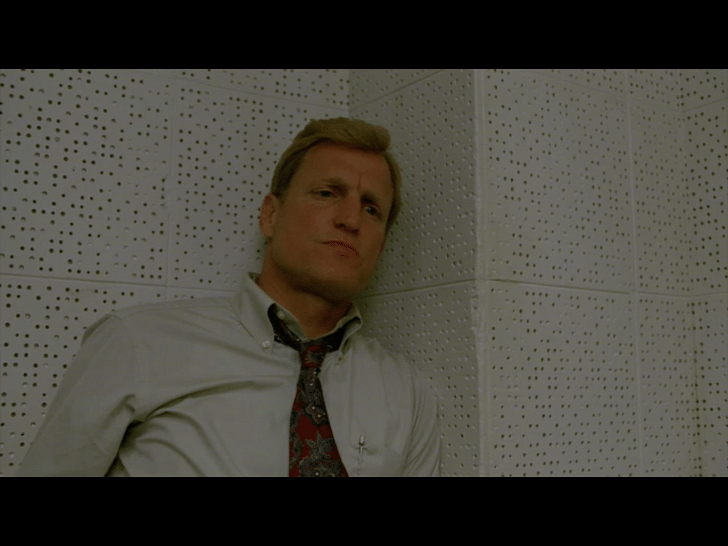

Twin Peaks and True Detective, each of which sashays through the spectrum of eccentricity, seems to ask: What lies dormant in the hearts of men? Well, murder, betrayal, theft, and undoubtedly some effed-up, mystical dream sequences. Most importantly, what separates a person's hard-won “well-adjusted” facade from his primal core? In the case of Detective Marty Hart, who spends the vast majority of True Detective being alternately horrified and exacerbated by darkness guru Rust Cohle, only a thin wall punctured with holes.

The seemingly innocuous material, with its neutral color and soft, yielding appearance, is a clear embodiment of dread. The panel, a material designed to soften harsh tones, is representative of that first unnoticed slip into insanity. Marty's dualistic nature, which he keeps at bay simply by denying its existence, is in danger of being brought out by Rust's zero-body-fat approach to dogma. Marty likes to think of himself as the equivalent of a dogcatcher in the homicidal realm: it's just a job, one that presents no lasting issues for a balanced dude. Of course, the problem with Marty's vision of himself is that he has no idea what to do with his darkest feelings. He ends up lying to everyone in his life, including himself. He gets angry with Rust's unending monologues because they do not allow for an unambiguous separation between the light and the dark. In this interrogation scene (watch below), Marty is watching Rust take apart a suspect, but he's also inadvertently reflecting on his own shaky sense of self. Is he a good family man, or a cheatin' drunk with access to firearms? Can he be both of these things as long as he keeps his text messages from public view? The silently absorbent wall is the manifestation of his agony, and in a way, the tumult of the entire first season.

The porous acoustic panel is used for a similar emotional purpose in the "Laura's Secret Diary" episode of Twin Peaks. Here the viewer is confronted rather relentlessly with the material, in a spinning shot that descends through the bleak, roughened holes and out into an interrogation room where Leland, the tortured father of victim Laura Palmer, is confessing to the murder of a man he believes killed his daughter. Everything about this sequence locks the viewer into the agony of Leland, who long ago breached the boundary between normalcy and derangement. The shrieking, atonal soundtrack seems to be a visitation of all of the sounds absorbed by the panel and Leland's memory, while the displaced sense of scale (are they in outer space? A dirty subterranean tunnel? The tract of some living creature?) encompasses the unfathomable scope of his madness. Before Leland says anything, we already know where he's been, thanks to the material journey we've just undertaken. This is partially due to the constant spinning movement of the camera. By eliminating any notions of "up" or "down," it enforces the idea that this isn't a clearly defined moral universe: it's one of constant change and relativity, and it's not exactly good-looking, either.

When examining the series as a whole, the use of the panel also contributes a far more complex emotional texture, both historically and culturally. Unlike True Detective, which skirts virtually any overt wackiness, Twin Peaks is a fictional universe that delights in polar extremes. The lug-headed joy of coffee and pie is given as much emotional weight as a nightmare murder in an abandoned freight car, and the viewer feels both poles keenly.

The lug-headed joy of coffee and pie is given as much emotional weight as a nightmare murder in an abandoned freight carAs one of the more materially-obsessed filmmakers, David Lynch's works are usually centered around taking the known and transforming it into the hysterically unknowable. Twin Peaks stands out among Lynch's work because it presses the raw scope of human experience into seemingly friendly, mass-market products. The opening sequence of the series prominently features an industrial saw mill. From the first few seconds, we're being signaled that products and materials are as vital a part of the story as the people within it. This makes Leland's confession and the viewers’ descent through the porous acoustic paneling both an ordinary consumer experience and the most extreme, horrible emotional journey one could possibly undergo. This mixture of banality and unfamiliarity, as realized in tangible materials, remains resonant almost a quarter century after the show originally aired. For its part, True Detective never misses an opportunity to incorporate images of abandoned industry and commerce in its backdrops and landscapes. Its title sequence is an homage to an industrial dream past from which we have just awoken; every material used in the series bears this echo of decay. The paneling behind Marty has absorbed the anxieties and failed plans of an entire society, and given back only muted darkness.

In our daily lives, we sleep on textiles, we walk across asphalt, we unburden ourselves on formica and wood and metal. We exhale into ceramics, and stare farsightedly out of glass. Our lives are not merely the journeys that happen around objects, but rather a nuanced balance between what is clearly defined and what can only be intuited. Those fictional universes that not only recognize but use the great dramatic power of materials give us a solid look into our ephemeral selves.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

1 Comment

A good visceral read like a true detective watch. Not familiar enough with Twin Peaks to integrate that into my thinking, but i do know that the architectural journal LOG name is a reference to the log lady (vague memory)........it appears to me after reading this that the material between sanity and insanity could be the "worn" material. The material with a readable history and at least an aesthetic quality of abandonment. The abandonment bit is important because you can have "worn" materials that appear exciting like a Soho loft apartment brick interior rented at $15k a month with Barcelona chairs sitting on stained old timber beams next to Italian modern kitchen. This would almost suggest the inert quality of this line between sanity and insanity material be abandonment. Been working on a large abandoned hospital to rental project for a few years now and every time I survey - little enclaves of homeless residences are encountered with human feces not far away from where they sleep and eat. The abandoned appear to find their homes in the abandoned. To be quite honest though I am not certain the homeless and nomadic are less sane than me. Donald trumps brass overdose is argueably just as insane? Got me thinking, tanks.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.