Love is the universal tether that binds kings to paupers and geniuses to fools. Perhaps this is why audiences are endlessly fascinated by psychopaths, serial killers, and other characters who seemingly live without love.

But what of those characters who love so much they become killers? The cinematic romantic bridges the gap between the well-adjusted lovelorn and the criminally loveless. Eventually, we are all wronged in love. Most of us cry it out over a long weekend, or even a long year. But for the die-hard romantics, disappointment in love can be the bloodshot-eyed prelude to premeditated murder. Forget long walks on the beach; these cinematic romantics plot their rage-obsessed responses to love affairs gone wrong under slanted, mullion-ridden windows.

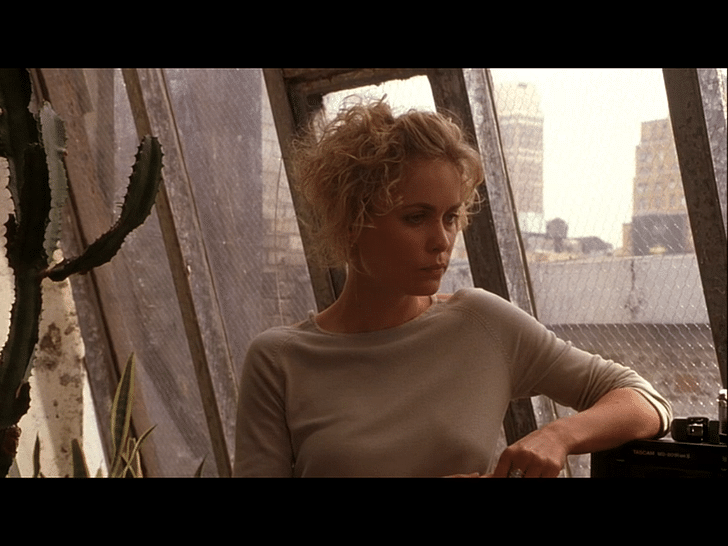

The titular characters of Tim Burton's adaptation of Sweeney Todd and Woody Allen's Melinda and Melinda are smoldering husks of betrayal. That Melinda and Melinda is a Woody Allen movie (and, admittedly, one whose concept far exceeds its execution) lends its main character perhaps an even darker edge. Allen, who consistently ranks as one of the most architecturally-attuned filmmakers, is keenest when he explores the murk of moral compromise in the name of "love." Melinda and Melinda's narrative conceit is formed when aWe are given to understand that Melinda feels no regret for her actions; in her romantic universe, the killing was the justified response to the betrayal. serious playwright and a comedic screenwriter take the basic details of a true story, and then respectively dramatize and satirize it, in an attempt to see which version feels more "real." In both versions of the story, Melinda is a suicidal wash-out fresh out of another failed relationship in New York City, showing up unannounced at a friend's dinner party. However, in the tragic version of this story, Melinda sits beneath a slanted window and reveals to her current beau that she murdered her former lover when he cheated on her. As she calmly reiterates how she bought the gun, staked out her cheating lover, and then killed him, her chilling compartmentalization seems to be manifested by the mullions of the window behind her. We are given to understand that Melinda feels no regret for her actions; in her romantic universe, the killing was the justified response to the betrayal. The heart wants what it wants, after all. A few months later, when Melinda's current beau ends up leaving her for another woman, Melinda decides to commit suicide by throwing herself off the ledge directly in front of the slanted window.

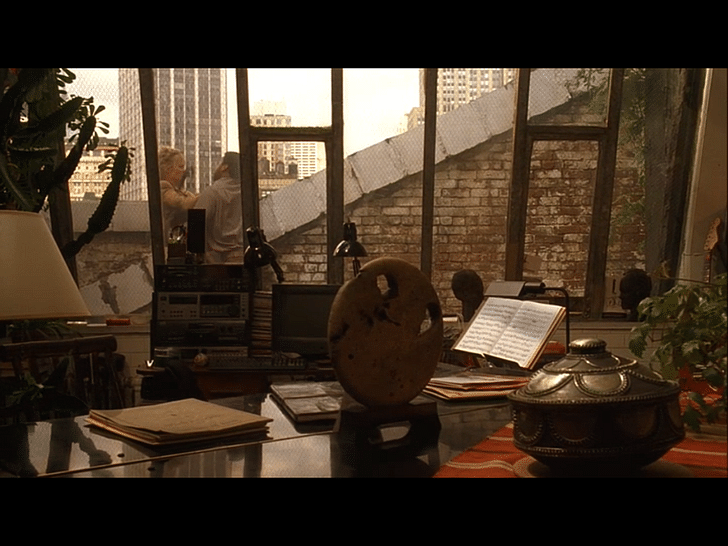

Meanwhile, the bleak pit of Sweeney Todd's world is carved out of political corruption, industrialization, and finally, the need to make a buck. In Tim Burton's musical version of this nearly two hundred year old tale, Sweeney Todd is falsely condemned to the penal colony of Australia, because a corrupt judge wants to marry Todd's wife. Todd eventually breaks out of prison and returns to sooty old London, where his former wife has been poisoned and his daughter is under the lustful eye of that same corrupt judge. He returns to his former role as the severe angle of the window's placement helps us understand that this is not a properly aligned love, but a messed-up, slanted one.a barber, taking up shop in an attic-like space with an eerily slanted window. He decides to take revenge on the judge by slitting his throat mid-shave, but along the way hits on a pretty profitable business model: murdering customers to make meat pies for sale to the underclass.

The window overlooking Todd’s murderous barber’s chair plays the exact same role as it did for Melinda. As he gutturally warbles his way through a showtune, calmly choosing the best angle from which to razor-dispatch his customers, the bleak London skyline outside reflects the bleak interior of his heart (see video below). Once again, the mullions represent the compartmentalization of his calculation and cunning, while the extreme angle of the window helps normalize his own twisted, passionate adjacency to the world.

The transparency of the windows, both in Melinda's New York and Sweeney Todd's London, not only treat us to spectacular views of architectural landmarks, but also represent the idea that the ardor of passion wishes itself to be seen: when a person is in love, they want the entire world to know their beloved. However, the severe angle of the window's placement helps us understand that this is not a properly aligned love, but a messed-up, slanted one.

Both films are infused with a manic energy that softens the reality of the actions committed on and off screen. In Melinda and Melinda, the intercuts between the serious and comedic playwrights discussing the movie, and the movie itself, perpetually break of the fourth wall. Unlike a traditional film, in which the viewers are encouraged to invest in the characters as if they are real, this film constantly reminds viewers that we are watching constructs — actors All they have left is a glazed portal into a bloodied farewell.whose tendencies are being purposefully exaggerated for our entertainment. As a musical, Sweeney Todd automatically forsakes realism in favor of hyperrealism. In this sense, both films are chauffeured tours through the grimier avenues of the human heart. We can empathize with the dark motives of these characters because we're being reminded, whether in the form of spontaneous song or the repeated break of the fourth wall, that these portrayals are purposefully inflated. But the raw, wrenching emotion wafts up and over this construct anyway.

Perhaps it is not surprising that the movies that explore this perverted union of passion and revenge choose to use such a ubiquitous feature as a window to do so. We have all encountered windows, much in the same way that we have all encountered heartbreak. However, in the murderous romantic context, these characters have already known the splendor of love, a joy that is now behind them. All they have left is a glazed portal into a bloodied farewell.

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.