The archives of the New York Times testify to the euphoria that accompanied the fall of the Berlin Wall in November of 1989. An article entitled “The End of the War to End Wars” reads: “Crowds of young Germans danced on top of the hated Berlin wall Thursday night. They danced for joy, they danced for history. They danced because the tragic cycle of catastrophes that first convulsed Europe 75 years ago, embracing two world wars, a Holocaust and a cold war, seems at long last to be nearing an end.”

Were the young Germans who “danced for history” atop the wall that had divided Berlin for two generations actually and unknowingly performing a danse macabre for liberal capitalism’s alternatives?

For some, the destruction of the Wall and the subsequent collapse of East Germany and then the Soviet Union signalled not just the end of the Cold War but also the ideological conflicts – between capitalism, communism, totalitarianism – that had defined the preceding centuries. The American political philosopher Francis Fukuyama famously wrote The End of History and the Last Man not long after, speculating that liberal democracy and its free market system had triumphed as the “final form of human government.” Were the young Germans who “danced for history” atop the wall that had divided Berlin for two generations actually and unknowingly performing a danse macabre for liberal capitalism’s alternatives?

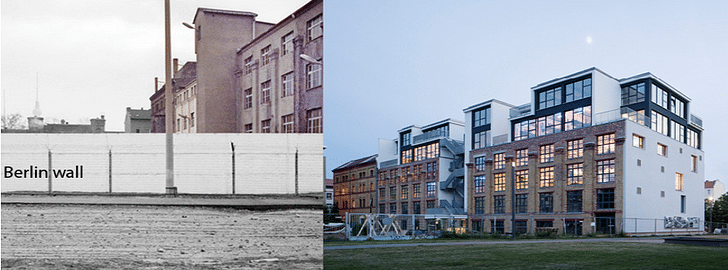

Today, a section of the Berlin Wall that once housed a German Democratic Republic (GDR) watchpost has been converted into Factory Berlin, a “start-up campus” hosted by Google. Where East German soldiers once kept watchful gaze over the gates to West Berlin, now entrepreneurs and developers from tech companies like Twitter, Soundcloud and Zendesk gather in multipurpose rooms watching screens. The conversion by Julian Breinersdorfer Architecture appears to be restrained and subtle, tastefully modernist and austere.

Five distinct buildings from the 19th to the 20th century together form Factory Berlin. The main structure – once the Oswald Berliner Brewery – was the one that was actually built into the Berlin Wall and served as a lookout. The other buildings contained small businesses, storage facilities, and housing after the fall of the Wall. The buildings were restored with attention to historical accuracy despite a lack of documentary photography. Plaster was removed to reveal the original brickwork. The interior circulation was updated to suit the needs of start-ups, like connecting together the formerly separate buildings with open staircases.

The basement of Factory Berlin, which once served as the “party den” of the former Nigerian ambassador to East Germany, appropriately contains event venues. Along the courtyard and its gardens, a series of office spaces house smaller start-ups. On top of the old, three-storey brick buildings, Julian Brenersdorfer Architecture built two more floors, painted white with Mondrian-esque black gridded windows. The design of these floors had to accommodate the uneven topography of the existent structures, a process that the architects elegantly describe as like “a cat lying down on a rugged stone wall, shifting and turning until it finds a suitably comfortable position for an afternoon nap.”

The Berlin tech industry has also been a bit like a cat, pawing the ground for a place to settle.

The Berlin tech industry has also been a bit like a cat, pawing the ground for a place to settle. Like the artists and musicians that flocked to the city for its comparably cheap rents and thriving scene after reunification, technologists found the city an ideal place to develop projects without the financial pressures one finds in other cities. But, as a New York Times article documents, the city is still a “backwater” compared to places like Silicon Valley. For the most part, companies that have emerged from Berlin tend to be copy-cats of American counterparts, replicated for a German-language audience. And, for a while, the money that had been passed around had been relatively small. But, Factory Berlin is perhaps one of the clearest signs that the city has cemented its role as a burgeoning locale for tech start-ups.

Today, Germany is the largest and most powerful economy in the European Union, one largely oriented around exports. At a superficial level, the strength of the German economy since reunification seems to evidence the success of neoliberal capitalism in the formerly divided state, and the tech industry is no doubt a part of that trend. But, while growing, Berlin still lags behind the rest of the country. For example, it’s unemployment rate of around 11% is significantly higher than the national average of 7%. Bringing in the tech industry was part of a strategic plan to pump out the city’s economy, orchestrated by mayor Klaus Wowereit (who famously coined the description of Berlin as “poor, but sexy”).

Moreover, the regions of the former-GDR still have a significantly lower standard of living and average annual income than West Germany. This is to say, reunification has not been fully successful (or perhaps complete); a recent poll found that over 50% of those living in the former-GDR feel that “life was better under communism.” After all, as another New York Times article contends, many in East Germany “suffered from 1989 and the sudden, even brutal switch to capitalism.”

The verdict is still out on whether or not the extreme wealth currently being generated by tech companies will exacerbate economic disparity or ameliorate it.

The question remains of whether or not tech money will trickle down to these less-enfranchised populations. A lot has been said about the detrimental effects of Silicon Valley moving north to San Francisco. In general, the emergence of a new class of super-rich “technorati” tends to displace families who are priced out of their old neighborhoods. Long time residents of San Francisco tend to complain about the homogenization of the city as well as the introduction of such segregated services as Google buses. On the other hand, gentrification is too complex a process to be contained in an easy polemic and, fundamentally, the character of a city is always in flux.

Twenty years after the fall of the Wall, almost a century after a revolution brought about the first of many communisms, the original injunctions of Marx have still not been fulfilled.

But as the skeletal structures of the dead communist state are repopulated with American companies, it is hard not to remark at what feels like the desecration of a corpse. Brought to Berlin by the same factors that drove artists (another group often denigrated for “gentrifying”), tech industries, if successful, will assuredly drive up rents as they bring in their “achingly cool coffee shops” and “factories.” And despite Germany’s strong economic performance compared to its Eurozone neighbors, recent studies have found an “alarming increase in urban poverty across Germany.” Relatedly, the country has the greatest wealth disparity in the EU; over a quarter of German adults have either no wealth or negative wealth due to debt while the wealthiest one percent have a personal wealth of at least $1.09 million dollars. The verdict is still out on whether or not the extreme wealth currently being generated by tech companies will exacerbate economic disparity or ameliorate it.

This is not to valorize the GDR or to denigrate the tech industry (or the design of Factory Berlin), but rather to remember the ghosts haunting the buildings that are currently being turned into “tech factories.” As Jacques Derrida wrote, largely in response to Fukuyama: “For it must be cried out, at a time when some have the audacity to neo-evangelize in the name of the ideal of a liberal democracy that has finally realized itself as the ideal of human history: never have violence, inequality, exclusion, famine, and thus economic oppression affected as many human beings in the history of the earth and of humanity.” Since the fall of the Soviet Union and the fall of the Berlin Wall, it is easy to get lost in a capitalist triumphalism. Perhaps nothing better encapsulates the ideals of such an ideology than the tech industry, which radically re-makes the office, the city, and the world in its own image, espousing a techno-utopianism. But that utopia breaks down in a reality of consumer goods that we spend more money on than we should and which end up in landfills, quickly piling up to create the morphology of our children’s dystopia. And twenty years after the fall of the Wall, almost a century after a revolution brought about the first of many communisms, the original injunctions of Marx have still not been fulfilled.

Writer and fake architect, among other feints. Principal at Adjustments Agency. Co-founder of Encyclopedia Inc. Get in touch: nicholas@archinect.com

4 Comments

Very nice project.

Nicholas I'd recommend if you want to keep the political going in your architecture crit, you could probably look at what I have considered the 3 downtowns of Berlin; look at them historically maybe - Kuferstendamm (west), Alexander Platz (east), and Potsdamer Plat (unified)....that's my opinion and from memory, did not feel like fact checking.

here's a jam i made once - enjoy

reagan never sounded so fly (mixed in Traktor - Armand van Helden, Link Wray, and Reagan's speech from '87 ) 12:00 minutes in, that's the famous bit.

also, are you still working on the post-internet series?

Elequontly elaborated .

The undercurrent to this report smelled like Lebbeus Woods was read, which is a good ting, but the Freudian slip indicates a clear agenda........just maybe, just maybe there has never has been an alternate economic model? I dare you to read the Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith and the only tid bit you will remember is a butcher a baker.....read Das Kapital by some guy named Karl and you will want to start a revolution, unless of course you are happy living in a neo liberal late capitalism blah blah whatever they call it now society like say England. The political Intelligence of the time in England never saw Karl as a threat, that is why he could find refuge there and write and write.....because scribble scribble scribble will only get you far in life. Get on a plane and go Visit Berlin.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.