"Factual communicability is privileged over the immersive experience, and architecture is presented as a set of instances—shown through models, drawings, photographs—rather than a process," the Canadian curator Carson Chan told me in a recent conversation. "Exhibited through representation, the architectural work more easily assumes the mantle of single authorship, where in situ, the same thought is almost impossible. In this sense, estrangement is built into the exhibition of architecture."

The current retrospective Frederick Kiesler: Architect, Artist, Visionary at Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin, embodies this problem of representation. As the first exhibition of the Austro-American architect’s work in Germany, the show was set to offer an exclusive look at Kiesler’s work from the heyday of avant-garde art and theatre in 1920s Berlin and Vienna, to his later career in design theory in the U.S. What makes Kiesler’s work unique is its proximity to an esoterically-informed art practice. Few of Kiesler’s lofty drawings ever became buildings, and he was best known for his surrealist exhibition and set design, rather than traditional architecture.

While decidedly comprehensive and didactically illuminating, the exhibition fails to reflect the crux of Kiesler’s rare approach. This seems to be a gross curatorial omission. The exhibition fails to reflect the crux of Kiesler's rare approach. The opportunity was ripe to use Kiesler’s iconic designs in the very form and structure of the exhibition, which instead came across as a dry, chronological and factual representation of his work—as though he had in fact been that traditional, lone architect his work vehemently opposed.

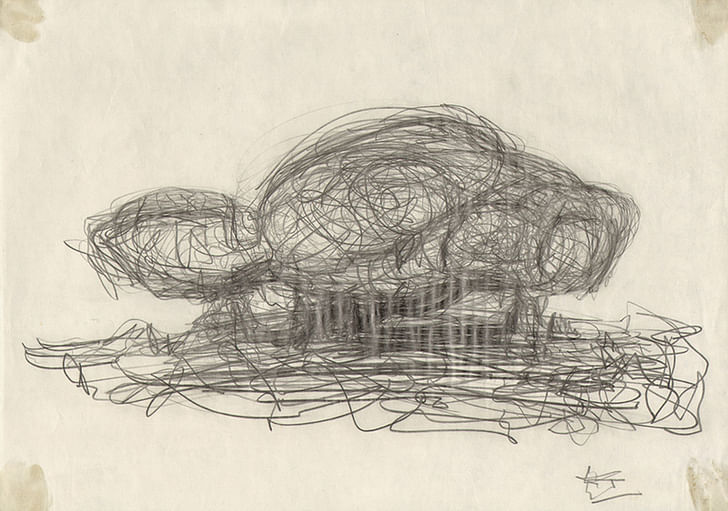

Born in Austria in 1890, Kiesler arranged the world premiere, in Vienna, of the 16-minute film ‘Ballet mécanique’, directed by Dudley Murphy and Fernand Léger, with Man Ray in 1924. He was heavily influenced by avant-garde art movements and these tendencies came across in his treatment of architecture and spatial practice. His polydimensional architectural drawings and plans were often compared to Surrealist automatic drawings.

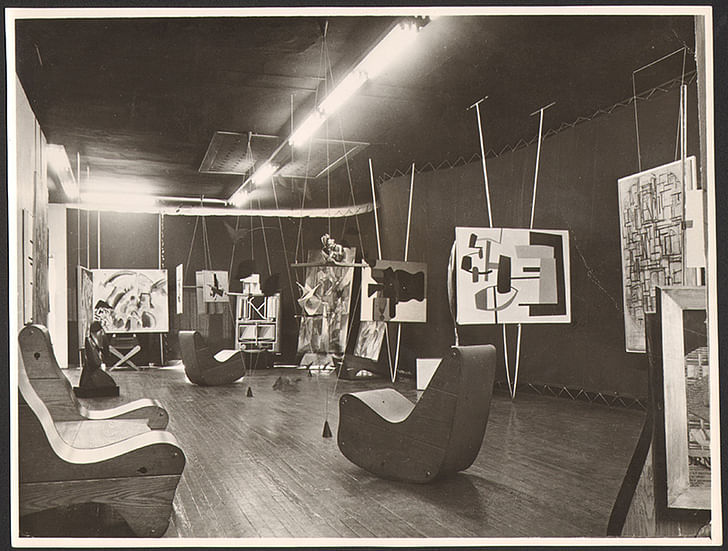

In the introductory text accompanying the exhibition at Martin-Gropius-Bau, the curators claim that Kiesler saw the visitor of an exhibition as akin to an actor on the stage: they were meant to “inhabit the artwork.” His exhibition and stage designs reflected that in their preoccupation with circularity and freestanding, modular elements that encouraged interaction. Kiesler saw the visitor of an exhibition as akin to an actor on the stage: they were meant to "inhabit the artwork." For his 1942 design for the exhibition ‘Art of this Century’ at the Guggenheim in New York, he presented many of the paintings at a remove from the wall, popping out into the visitors’ space and revealing the materiality of their backsides. He even added ergonomic seats, which he called “correalist instruments,” scattered throughout the exhibition to encourage bodily engagement. Yet the retrospective in Berlin largely went for the tell rather than show approach to communicating these novel strategies. Moreover, the exhibition played into the cult of personality afforded to white, male architects of Kiesler's generation by including things like the worn suitcase he used to travel to New York in 1926. This kind of institutionalization of Kiesler as a heroic example of the American dream made manifest is at odds with his occult theories and bohemian, Weimar Republic beginnings.

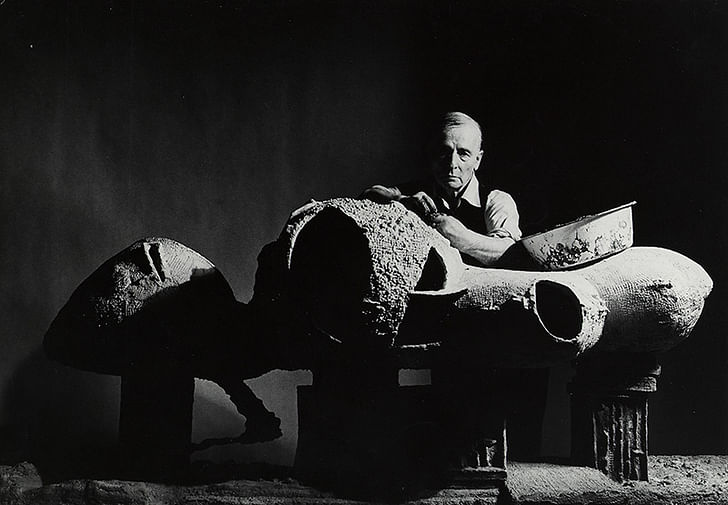

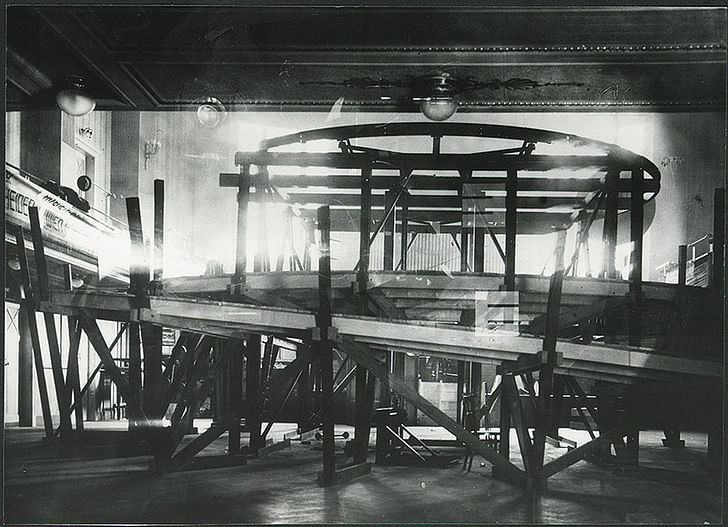

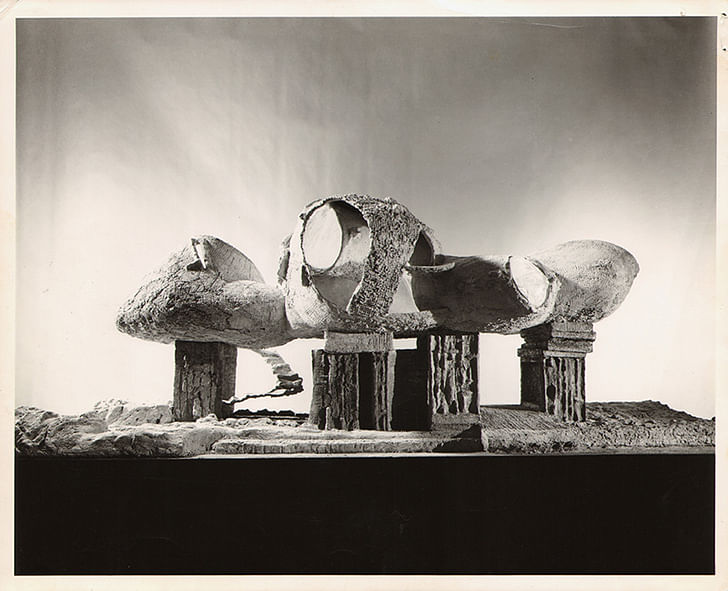

Kiesler’s designs were often composed of circles and infinity loops, from his very first ‘Raumbühne’ (Space Stage) in Vienna in 1924 to his larger scale ‘Universal Theater’ designs in the U.S. in the 1960s, and his well-known ‘Endless House’ models. Only later were these favoured forms revealed to be part of a holistic design theory, known as ‘Correalism.’ At the heart of his theoretical output was an aim to re-unify the arts using systems theories from biology and emphasizing the correlation and co-reality of nature, humanity and technology. In many ways, his theory preempted the Whole Earth and Californian ideology generation of the ‘60s and later discourses around the Anthropocene, by focusing on alternative education, mobility, holism and self-sufficiency. He wanted to do away with the column and other vertical support structures of its kind, creating rounded, flexible spaces instead. Womb-like shapes dominated his model-making, and materials were often rough and earthy. A strong visual language of the maternal ‘home’ emerged in Kiesler’s designs, including one of his last drawings of the ‘Grotto for Meditation’, done before his death in 1965. When dealing in so-called visionary or utopian architectural forms today, to what extent is it possible to give them a material reality?The unbuilt structure was portrayed in blueprints with the abstract contours of an ultrasound, and drew on natural elements like seashells and water for its composition. Other inclusions stuck out across the otherwise somber display: a photo shoot of Kiesler’s 1935 nest tables were erotically-charged with a woman straddling the furniture suggestively in the first image, her close-up back inexplicably bare in the last, with the table almost invisible in the background.

Despite the anarchic and libidinous qualities of Kiesler’s work, the show at Martin-Gropius-Bau chronicled a lackluster biography, from his young, creative beginnings in the avant-garde theatre and art world to his period of struggling “between vision and compromise” (as the section was labelled), wherein he undertook a series of insignificant commercial projects across the U.S. Whether or not estrangement is truly built into the exhibition format—as Kiesler would surely argue it need not be—many opportunities to channel Kiesler’s philosophy in the curatorial process of the exhibition were missed. Representation through models, drawings and photographs dominated, where physical applications might have done due justice to Kiesler’s expanded practice. But his dynamic oeuvre also begs the question: when dealing in so-called visionary or utopian architectural forms today, to what extent is it possible to give them a material reality? Through Kiesler’s exhibition and set design, these visions became a vehicle and support for other creatives acts, and an integral part of a communal vision that refused to focus on single authorship.

Alison Hugill is an editor, writer, and curator based in Berlin. She is managing editor of Berlin Art Link magazine and contributes to Sleek Magazine, AQNB, Momus, Rhizome, and Artsy. Hugill has an MA in art theory from Goldsmiths College, University of London (2011). Her research focuses on ...

2 Comments

Wowzers. That model is amazing

for "Space Stage" or "Endless House"...Both?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.