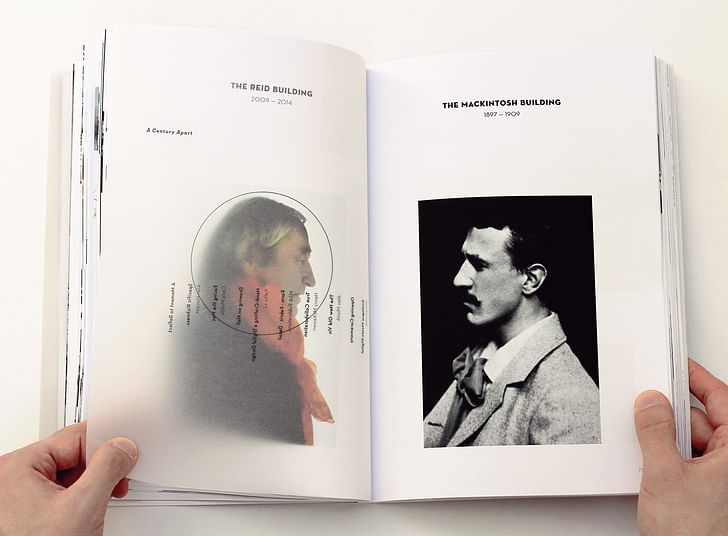

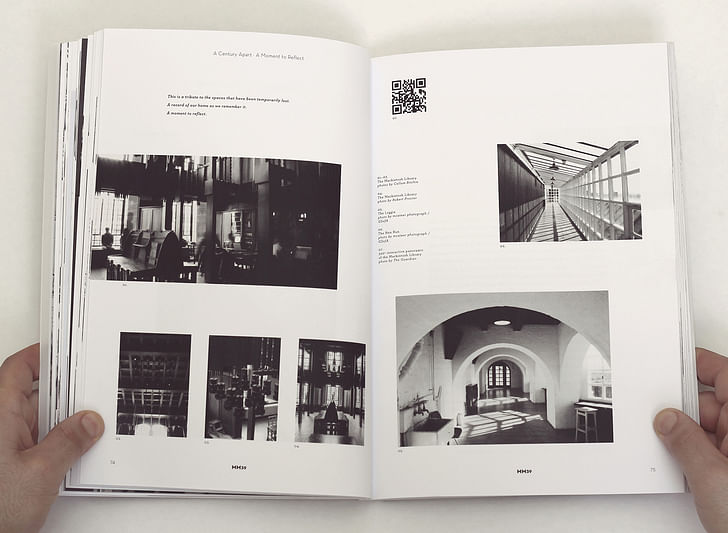

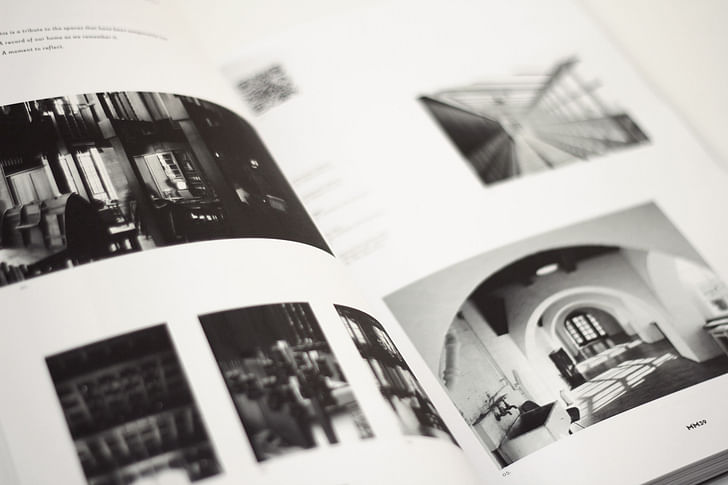

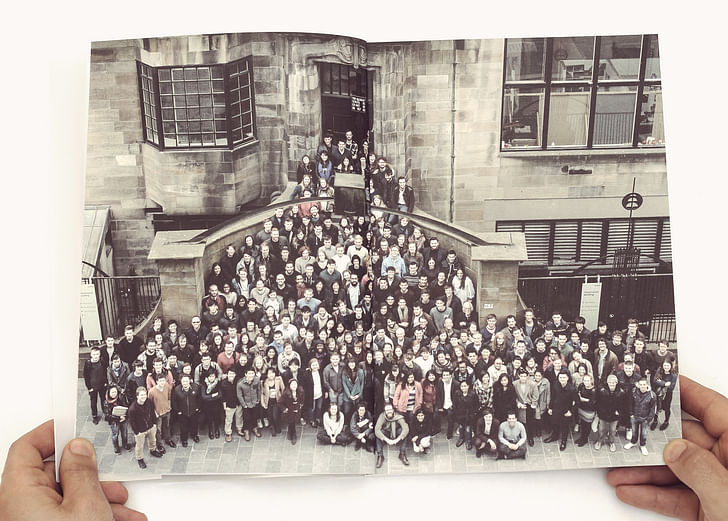

The Glasgow School of Art’s architecture is a concise conversation between old and new. Recent events on campus, however, tipped the discussion in favor of the contemporary — a new building by Steven Holl Architects opened, and just a few weeks later, a fire ravaged the school’s historic Mackintosh Library, directly across the street. This conversation between the traditional and contemporary, and the eventual transition of the contemporary into the traditional, is built into MacMag, the architecture school’s annual publication.

MacMag serves a variety of functions, showcasing student work from across disciplines, alongside editorial by both students and professionals. Like the school, the publication is concerned with harmonizing old and new, not casting them as dissonant.

For MacMag39, our featured Screen/Print issue, we’re focusing on an interview with Steven Holl, architect of the school’s new Reid Building. An all-purpose arts education space for all disciplines, the Reid was designed as a home for departments to mingle while working, and takes cues from its neighbor directly across the street, the Mackintosh. Now, with the help of a hefty chunk of government change, the Mackintosh is being restored to its original glory — a modern masterpiece of its time, over a century ago.

In his interview, Holl speaks with editors Sofi Campbell, Lawrence Khoshdel, Natalie Pollock and Arseni Timofejev about his use of digital and analogue tools, and his love of Siri.

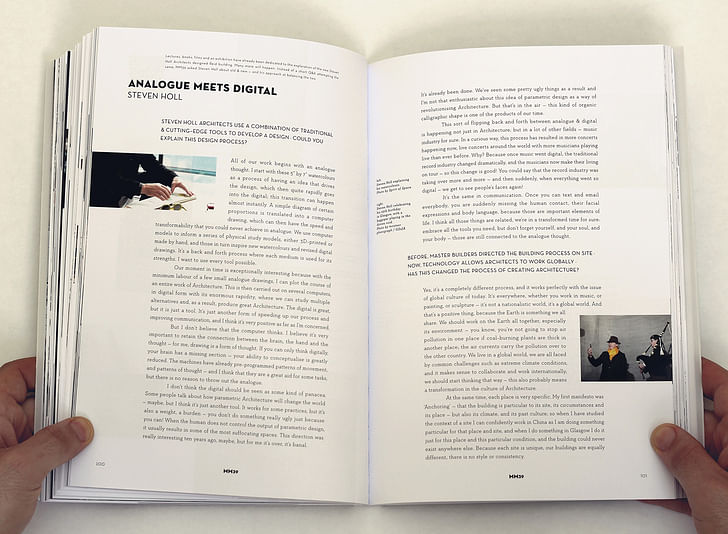

MacMag editors interview with Steven Holl, as featured in MacMag39:

MacMag: Steven Holl Architects use a combination of traditional and cutting-edge tools to develop a design — could you explain this design process?

Steven Holl: All of our work begins with an analogue thought. I start with these 5” by 7” watercolours as a process of having an idea that drives the design, which then quite rapidly goes into the digital; this transition can happen almost instantly. A simple diagram of certain proportions is translated into a computer drawing, which can then have the speed and transformability that you could never achieve in analogue. We use computer models to inform a series of physical study models, either 3D–printed or made by hand, and those in turn inspire new watercolours and revised digital drawings. It’s a back and forth process where each medium is used for its strengths. I want to use every tool possible.

Our moment in time is exceptionally interesting because with the minimum labour of a few small analogue drawings, I can plot the course of an entire work of Architecture. This is then carried out on several computers, in digital form with its enormous rapidity, where we can study multiple alternatives and, as a result, produce great Architecture. The digital is great, but it is just a tool. It’s just another form of speeding up our process and improving communication, and I think it’s very positive as far as I’m concerned.

But I don’t believe that the computer thinks. I believe it’s very important to retain the connection between the brain, the hand and the thought — for me, drawing is a form of thought. If you can only think digitally, your brain has a missing section — your ability to conceptualise is greatly reduced. The machines have already pre–programmed patterns of movement, and patterns of thought — and I think that they are a great aid for some tasks, but there is no reason to throw out the analogue.

I don’t believe that the computer thinks. I believe it’s very important to retain the connection between the brain, the hand and the thoughtI don’t think the digital should be seen as some kind of panacea. Some people talk about how parametric Architecture will change the world — maybe, but I think it’s just another tool. It works for some practices, but it’s also a weight, a burden — you don’t do something really ugly just because you can! When the human does not control the output of parametric design, it usually results in some of the most suffocating spaces. This direction was really interesting ten years ago, maybe, but for me it’s over, it’s banal.

It’s already been done. We’ve seen some pretty ugly things as a result and I’m not that enthusiastic about this idea of parametric design as a way of revolutionising Architecture. But that’s in the air — this kind of organic calligraphic shape is one of the products of our time.

This sort of flipping back and forth between analogue & digital is happen- ing not just in Architecture, but in a lot of other fields — music industry for sure. In a curious way, this process has resulted in more concerts happening now, live concerts around the world with more musicians playing live than ever before. Why? Because once music went digital, the traditional record industry changed dramatically, and the musicians now make their living on tour — so this change is good! You could say that the record industry was taking over more and more — and then suddenly, when everything went so digital — we get to see people’s faces again!

It’s the same in communication. Once you can text and email everybody, you are suddenly missing the human contact, their facial expressions and body language, because those are important elements of life. I think all those things are related, we’re in a transformed time for sure: embrace all the tools you need, but don’t forget yourself, and your soul, and your body — those are still connected to the analogue thought.

Before, Master Builders directed the building process on site. Now, technology allows architects to work globally. Has this changed the process of creating architecture?

Yes, it’s a completely different process, and it works perfectly with the issue of global culture of today. It’s everywhere, whether you work in music, or painting, or sculpture — it’s not a nationalistic world, it’s a global world. And that’s a positive thing, because the Earth is something we all share. We should work on the Earth all together, especially its environment — you know, you’re not going to stop air pollution in one place if coal–burning plants are thick in another place; the air currents carry the pollution over to the other country. We live in a global world, we are all faced by common challenges such as extreme climate conditions, and it makes sense to collaborate and work internationally; we should start thinking that way — this also probably means a transformation in the culture of Architecture.

At the same time, each place is very specific. My first manifesto was ‘Anchoring’ — that the building is particular to its site, its circumstances and its place — but also its climate, and its past culture; so when I have studied the context of a site I can confidently work in China as I am doing something particular for that place and site, and when I do something in Glasgow I do it just for this place and this particular condition, and the building could never exist anywhere else. Because each site is unique, our buildings are equally different, there is no style or consistency.

It was quite different for Mackintosh: he didn’t have to do something in China, or New York, it was just in the UK. Most of his work is here in Glasgow: he perfected a language that fits in this context and is carried through in his few buildings, but even more so in interiors, furniture and the fixtures — that was an amazing moment in history.

Today, the world is different — it keeps getting smaller — and so it should be, I would not want it any other way. It makes sense to make the most of our possibilities, and use the technologies that bring us closer. For example, we have two offices, one in New York and the other one in Beijing — because of the time difference and the ability to share files on one digital server, we can work on some projects 24 hours a day — one office works while the other sleeps. In the same way, when we were collaborating with the School alumnus Martin Boyce to create his ‘Thousand Future Skies’ entrance piece, we did not necessarily have to work on site, side by side — instead we had a series of meetings in Glasgow and New York, and worked from the same digital files, so the two pieces were integrated with total accuracy.

Digital connectivity does speed everything up enormously, but this can also be overwhelming. How do you find the time to be involved in, and co-ordinate, all those decisions?

Technology is constantly improving, and lets us communicate more things more freely. Sometimes, it’s hard to even imagine how we worked before. For example, I quit talk- ing on the phone three years ago — this totally changes my life, I have much more time, because I don’t have to deal with any “please return this call” or “can I call you back?” — No, you cannot call me: talk to me face to face, or text and email me, that’s it.

I never liked the phone. I know so many people who spend most of their time on the phone doing business, but it’s not really efficient. If some information has been transferred to you via telephone, Context, and the understanding of one’s moment in time, and the connection to ideas — those are all incredibly important, and without them one cannot create real works of Art.then you’ve got to re–transfer it to the people who are working on the project. And I run the offices in New York and Beijing, so that would be a lot of time dedicated to just that. Instead, I can send an email, copy everyone who’s working on the project in it, and they can read it when they have the time, instead of constant meetings and schedule conflicts. And I can do it from anywhere in the world: for example, I had to travel for 48 days straight. And nobody even knew I was gone, because I was communicating with everybody, I sent them watercolours, concept drawings, and they sent me back PDF packages of their progress.

By the time I was back, our new design was already modelled and 3D–printed for a thorough review face–to–face, with the Beijing office engaged via Skype.

Recently, I also started using Siri on my iPhone. Now, instead of typing all the countless messages on the small screen, I can press Siri and just talk — it sends two paragraphs to the Beijing and New York offices at once, and I can go back to designing. If you think about all this, it’s really amazing — I am totally for every digital improvement of life.

Finally, a fun question: if you had the chance to collaborate with Mackintosh, Louis Kahn or Le Corbusier, who would you choose?

I don’t think any of these three would want to collaborate! That would be like a fight, a head battle. I don’t remember them collaborating with any other Architects.

Because each site is unique, our buildings are equally different, there is no style or consistency.In a way, our Glasgow project has been a dialogue with Mackintosh, and he’s always been an important influence and source of inspiration, from the time I was a student. In fact, I graduated from the University of Washington with a good knowledge of his work, and had not even heard of Le Corbusier!

After I graduated, I was interviewed and offered a position with the studio of Louis Kahn, but did not quite make it in time: unfortunately, he died in March 1974, just before I could move to Philadelphia. His works and ideas are very inspiring, and have always been an important point of reference.

But above all, I am still completely amazed by Le Corbusier, because of the poetics of his texts: their depth, their reach. I have a library with, probably, every book on Mackintosh; and I think I have every book on Louis Kahn, but my section on Le Corbusier is much larger and in his case, I don’t even have all his books! So that’s the direction I would go, because I just find the breadth and depth of his investigation, and the ability to do new things right up to the end extremely curious. After his famous white period of the pilotis and the Five Points of Architecture, he’s done so many fascinating experiments: look at Maisons Jaoul, or the Heidi Weber Museum, and Ronchamp, and his work in India — where did all this come from?! It’s a completely different language, and I find all this extremely fascinating.

Whenever people try to copy Le Corbusier — they don’t really get it! You know, urbanism is dangerous without the Architecture, and so whenever you see a tower building that they blame on Le Corbusier — he didn’t do that! That’s not even Architecture! Context, and the understanding of one’s moment in time, and the connection to ideas — those are all incredibly important, and without them one cannot create real works of Art.

MacMag39 also includes content from:

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured MacMag39, from the Mackintosh School of Architecture at the Glasgow School of Art.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.