Log is an insistently literary architecture publication — that is, it prioritizes text far over image. Rejecting “the seductive power of the image in media”, Log tries to communicate the significant aspects of contemporary architectural discourse within the diverse and often divisive international architectural community. This can be seen as an overt move away from the dominating form of architectural discourse around the globe, one perpetuated by flashy images with little or no context, let alone criticality.

“New Ancients”, Log’s 31st issue, focuses on contemporary practitioners working openly with history. Guest editors Dora Epstein Jones and Bryony Roberts drew deliberate parallels to the 17th-century arguments between the “Ancients” and the “Moderns” at the Academie française, the definitive community on all matters of the French language*.

Our Screen/Print excerpt from “New Ancients” is “Spherical Penetrability: Literal and Phenomenal”, by architect and professor Emmanuel Petit. A founding partner of EPISTEME Architecture, Petit is also the author of Irony, or, The Self-Critical Opacity of Postmodern Architecture, and teaches at The Bartlett.

Spherical Penetrability: Literal and Phenomenal

by Emmanuel Petit

History, precedent, antecedent, reference: in the literature of contemporary architecture these words, and others like them, are often used as synonyms. We are familiar with their use and rarely seek to analyze their application. They have furthermore been dismissed as old hat and rearguard for the reason that they tend to be ascribed to a particular strand of the rise of digital culture in architecture since the early 1990s has turned our discipline away from its obsession with the semiosis of historical meaningpostmodernist thought that has been eroded in many different ways in the last two decades. In particular, the rise of digital culture in architecture since the early 1990s has turned our discipline away from its obsession with the semiosis of historical meaning and toward an interest in formal immanence and the related digital form-finding processes – which, it has been argued, render the search for historical precedents arcane or irrelevant. As a result, today’s formal avant-garde appears to eschew all historical content and instead sees architecture as the edited instantiation of the inner structural logic of algorithms – often “fed” with the asignifying information of Big Data. However, we are in a moment in time when the experimentation with complex digital form has begun to lose the lure of its initial naiveté, which calls for its conceptual integration into the disciplinary discussion. A more discerning understanding of history will make clear that the notion of precedent cannot simply be eliminated from our lexicon with the hope that in its wake a space would open up for the genuinely new and unprecedented. Nevertheless, precedent has come to mean something different today than it did three or four decades ago.

Among the classical disciplines, jurisprudence is a relevant model for architecture to understand how disciplinarity can hinge on its own history of ideas. In common-law legal systems, the notion of stare decisis (to stand by decisions) defines precedent as a “rule of law established for the first time by a court for a particular type of case and thereafter referred to in deciding similar cases.” The judiciary principle continues with an addendum – today’s formal avant-garde appears to eschew all historical contentet non quieta movere (and not disturb the undisturbed) – stating that courts should not disrupt settled matters. This principle directs that decisions of high and supreme courts become binding precedents for lower court decisions if the question resolved in the precedent case is the same as the question to be resolved in the pending case (and if no altering or additional facts distinguish the new case from the precedent). In legal jurisdiction, every new case needs to have its analogies to previous cases formally established before precedents can be invoked as guiding or binding principles. So while lower courts are obliged to follow the ruling of precedents, legal discourse at the level of high and supreme courts is not as much about applying precedents to new problems as it is about formally evidencing the extent of analogies between earlier cases and current ones. This is the way in which meaningful arguments get constructed and in which a discipline can evolve. To learn from history at this level of the disciplinary apparatus does not mean simply to invoke previous models, but to self-consciously invent the relationship between the present and the past. Both critical and speculative humanities – including jurisprudence and also architecture – always have such a historical element at their core.

The question is: Precisely which types of analogies with the past can be transposed into the contemporary digital culture of architecture so that new designs become thinkable, rather than merely realizable?

Such an inquiry can lean on a useful distinction put forward by Colin Rowe in the first of his “Transparency” essays, which he wrote with Robert Slutzky – the differentiation between the literal and the phenomenal in architecture. Though foremost an argument about formal analysis in architecture, the theory is grounded in the study of specific historical precedents. Rowe and Slutzky mobilized particular aspects of cubist painting and Le Corbusier’s architecture to create a mode of analysis that led away from early and mid-century modernism; they established a very useful disciplinary discussion that hinged on the precedent cannot simply be eliminated from our lexicon with the hope that in its wake a space would open up for the genuinely newcomparative study of architectures throughout history. We can agree with Rowe and Slutzky that at a high level of discourse, architecture is invested in continually finding new analogies with precedents and rendering them phenomenal. In their definition, the phenomenal transgresses the realm of the factual and is always invested in a culture of interpretation of the past; in other words, a literal condition of architecture becomes phenomenal as a result of its relation to the history of precedents. At the risk of succumbing, myself, to what Rowe might have rejected as a zeitgeist argument, I suggest that between Rowe’s last lectures and texts in the 1990s and today, the technological and cultural grounds of architecture and architectural theory have evolved considerably, and therefore new analogies with the past need to be rendered operative for our discipline. Because of the way architectural designs are originated today in the new digital design environment, the analysis of precedents could be inspired by the logic of more contemporary media of representation rather than cubist painting. Rowe had hoped that his analytic formalism could be ahistorical and therefore weather the advent of a new technological and cultural episteme; while his invocation of precedent is still a useful model, the analogies between past and present architectures must now be reconceptualized.

* * *

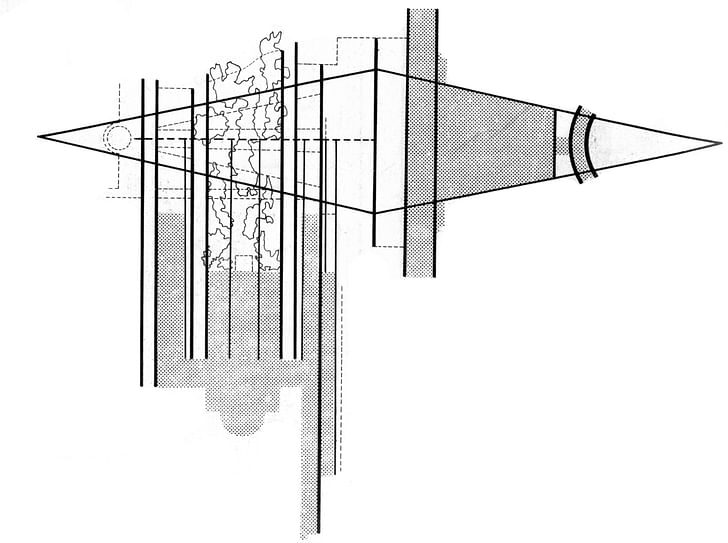

In their 1963 essay, Rowe and Slutzky presented Le Corbusier’s League of Nations project from 1927 as the epitome of a space built on phenomenal transparency, and contrasted the building’s assertive planes – “like knives for the appropriate slicing of space” – to theprecedent has come to mean something different today than it did three or four decades ago. “amorphic outline” of Walter Gropius’s 1926 Bauhaus Building. Theirs was an argument about the analytical and geometrical rigor of Corbusier’s building complex – conceptualized as a series of spatial elements inserted in a matrix of parallel striations. By abstracting one spatial dimension into a simple stratification, they made it possible to compare the forms of the various sliced planes and register their formal similarities and differences. This method of analysis was two-and-a-half-dimensional in that the attributes of space were compacted into a series of flat diagrams not unlike the compression of different viewpoints onto the flat canvas in cubist painting. Each one of the diagrams contained “intimations of depth” or “deep space” and could only be decoded in an active intellectual act. Deep space was thus not simply a physical attribute of a building but the result of a psycho-philosophical reading by an ideal perceiver of architecture whose visual literacy is built on the knowledge of specific historical precedents.

Though ostensibly conceptualizing a modern building of the 1920s, Rowe’s analytical tool reflects the concept of dialectic space that would lead to the postmodern in architecture, in particular that the oscillation between two incongruous formal states of deep space – phenomenal transparency being “an argument between a real and ideal space” – is the engine that produces formal complexity. For this intricate structure of deep space to be readable then, it has to be disassembled into a series of discrete formal fragments. In general, postmodern architecture always derived its formal richness from the confrontation between the absolute and the contingent – between the ideality of intellectual form and the reality of actual form.

Today, however, the assumption that architectural form is decoded from the vantage point of an ideal observer in the dialectic between real and ideal diagrams seems out of sync with the way architects conceive and think of spatial structures. With today’s ubiquitous computer-aided design technology, it is highly questionable whether Le Corbusier’s belief that the plan is the generator (which proved so central to Rowe’s flat view of the Precisely which types of analogies with the past can be transposed into the contemporary digital culture of architecture“mathematics” of a building) can be upheld as a mantra. Now that all buildings have turned literally transparent as wireframes on computer screens, the generator is mostly volumetric to start with and can be represented and thought of as a diaphanous and approximate sphere of relationships rather than a rigid (fragmentary) geometry. An example of such a volumetric diagram can be found in UNStudio’s Möbius House, which builds on the twisted and involuted logic of two lines that contain volumes of space and intersect at specific points. This building cannot be analytically striated to yield information about deep space in terms of Rowe’s linear and layered notions of transparency and mathematics; its rational diagram, which was first conceptualized in the 19th century by astrologist and mathematician August Ferdinand Möbius, loops in all directions of space rather than simply from the inside of the building toward its facade. Despite Möbius House’s partially literal transparency in terms of windows, no standpoint in space affords the total view of the diagram; instead this requires a volumetric or spherical reconstruction. The formal clues for such a mental construction are distributed through space rather than compressed into the flat surface of a facade.

When Rowe and Slutzky contrasted the stratified diagram of the League of Nations project to the “amorphic quality” of the Bauhaus, they anticipated a critical difference that would become, in the 1990s, a central theme of discussion in architecture – Gilles Deleuze’s distinction between the smooth and the striated. The Bauhaus was deemed much less complex because all formal differences were incorporated into the continuum of synthetic form and thus rendered illegible: “By contrast [to the League of Nations],” Rowe and Slutzky wrote, “the Bauhaus, insulated in a sea of amorphic outline, is like a reef gently washed by a placid tide.” The word choice amorphic is telling because it was coined as a critical term less than two decades before, in 1946, when the American geneticist Hermann J. Muller used it to denote the kind of genetic mutation that disrupts the translation of the genetic code. The amorphic is a “genetic null” mutation that causes the loss of all genetic information from one generation to the next. In Rowe’s understanding, one can assume that the Möbius House would be a “genetic null” mutation in that the code or mathematics of precedents is illegible in terms of the particular history of precedents he had proposed.

However, we have reached a point in history where a majority of architectural projects is based on morphological attributes that would place them in Rowe’s category of the amorphic – including the Möbius House. This does not mean that architecture has disengaged from its history but rather that Rowe’s model of precedent and formal analysis can be broadened considerably to include the qualities of the amorphic. Not least because he had bracketed these morphological features out of his theories, architectural culture in the early 2000s switched to a type of discourse that foregrounded the search for a terminology of aesthetic effects. But this trend is running out of steam, as it is fundamentally aimed at producing a mere inventory of sensations without relation to the broader disciplinary context and history. The digital means of form generation, analysis, and representation should make it possible to read architectural form in a different way in relation to precedent, and therefore to realize that the term amorphic is used by analysts of form when they are unable to explain the relation of that form to the system of historical analysis used.

Log is a project of Anyone Corporation, a non-profit architecture organization based in New York City that also organizes conferences and seminars.

Also featured in Log, “New Ancients”:

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured Log #31: The New Ancients.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

3 Comments

" the rise of digital culture in architecture since the early 1990s has turned our discipline away from its obsession with the semiosis of historical meaning and toward an interest in formal immanence and the related digital form-finding processes – which, it has been argued, render the search for historical precedents arcane or irrelevant. As a result, today’s formal avant-garde appears to eschew all historical content and instead sees architecture as the edited instantiation of the inner structural logic of algorithms – often “fed” with the asignifying information of Big Data."

WTF? Is semiosis even a word? In San Francisco, there was a bus add saying we are all data nerds. Is this this meme is meant to justify anything that's data driven? This is what they must mean by zeitgeist, when the avant guard and the corporations are on the same page.

"However, we are in a moment in time when the experimentation with complex digital form has begun to lose the lure of its initial naiveté, which calls for its conceptual integration into the disciplinary discussion. A more discerning understanding of history will make clear that the notion of precedent cannot simply be eliminated from our lexicon with the hope that in its wake a space would open up for the genuinely new and unprecedented. Nevertheless, precedent has come to mean something different today than it did three or four decades ago."

Who ever tells you that we are eliminating precedence is out of their mind. At what ever level, precedence is how we work, whatever the final aesthetics or formal language if one prefers.

"But this trend is running out of steam, as it is fundamentally aimed at producing a mere inventory of sensations without relation to the broader disciplinary context and history. "

Maybe architecture shouldn't be so reliant on trends and the market that seems to need them in order to push more merchandise on us. Then again, trends are how the avant guard set themselves apart, so they will never truly go away, or should they. It just seems they come at the same rate action movies cut their action scenes.

"The digital means of form generation, analysis, and representation should make it possible to read architectural form in a different way in relation to precedent, and therefore to realize that the term amorphic is used by analysts of form when they are unable to explain the relation of that form to the system of historical analysis used."

I don't think computers will necessarily change how we read architectural form, at least on a sensory level. It certainly has changed the production of it at all levels though, enabling trends to proliferate at an amazing pace. But regardless of production, actual form will still be read in three dimensions, and not on a 2-d screen of a 3-d image.

I am not that old but I find this whole intro text by Amelia quite illuminating and entertaining. As a kid my parents told me comic books were for lazy kids who pissed their pants and after years of roaming libraries I was certain 'real thought' comes in text format only. .........and to my point in relation to Thayer-D's comments the essay posted here so far is my least favorite in this issue, it smells like a text about computers by another generation.....the whole spherical thing (another essay also deals with this) just seems like a silly analogy if you took the mathematics behind it literally.....I do not know if it was an editorial move to put Petit's essay up against Amelias intro but in that critical regard it speaks volumes the course of the architectural discourse on theory has taken (or lack thereof). semiosis vs pinterist -like wine vs coors light - both will get you drunk, so whatever......so far "Neo-naturalism" by Zeynep has been my favorite, just lays it all out, a good intro essay presumably - a 'this is how everyone is thinking now, do you see the problem?' Essay

from referenced essay by Quondam -p142 of Log 31

"Architects despise copies, and in so doing refuse to recognize them, and, by extension, regulate them. In that context, different from other overregulated creative realms, to explicitly embrace the copy will not be an attempt to crack open the contradictions of copyright logics. Instead, it will preserve the way copying works in architecture by revealing an operation that historically has been kept secret. Architects, copy! It is an active strategy of resistance against the commodification of architectural knowledge."

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.