AfterShock is a non-conclusive series on Archinect that grapples with the impact and responsibility of contemporary architectural design, hoping to instigate dialogues on how to make architecture more accountable.

Let me open with a disclaimer: I am not an architect, nor have I ever contracted one. I can imagine that the relationship between architect and client, in terms of rapport, can be as diverse as any relationship -- where compromise, communication, and explicit contracts are vital to ensuring that no one gets screwed over. Ideally, when it comes to asserting creative freedoms, each party is convinced of the other’s expertise, and knows when to back down and let Architect Jesus (or Client Mary) take the wheel. The variety of relationships can vary as dramatically as the typology of the project. The commercial client may not provide as much budgetary slack as a private one, and economic/cultural climates can turn architects away from provincial project spaces toward environments with lower hanging fruit. Successful projects can defy rules, failures can follow them, and the notion of a “successful” project can be disputed to no end.

Architects and clients must empathize with the users of their projects, and increasingly those users are relating experientially and aesthetically to urban-life as an interactive commodity. But the third party in the conversation, the user, will always be on the receiving end of this relationship, although not so clearly the determinant of its success. Architecture is, by and large, meant to be encountered and used by a person, and while that may sound glib, its interactivity distinguishes it from other classic art forms. It is in a way a designed object, but the sensory data it emits aren’t as tangible or obvious as, say, from a piece of furniture or a nifty clock radio. Architecture as an art object is realized through inhabitation, whether of people or of function (an apartment houses people; a library houses information; etc.), a requisite that necessarily takes time and performance. While it may be obvious when a piece of architecture succeeds in terms of function (is it raining inside the building?) it’s harder to quantify why an individual user finds a space remarkably successful, without citing poetics of emotional or intellectual rhapsody. So when considering the “generic” user, how does one relate to the architectural art form, and how should those creating architecture understand that relation?

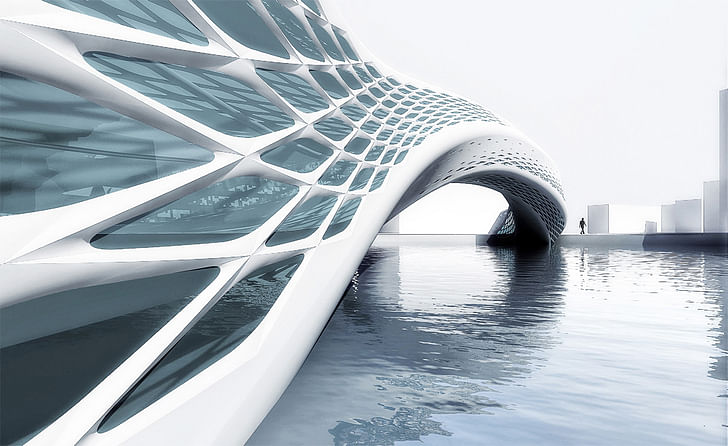

Architectural aesthetics are congruous with any other art’s aesthetic -- inexorable from history, and inevitably shifting. So into what realm has that aesthetic shifted at this moment, or where does it seem to be headed? Is the dominating aesthetic determinant geography, or technology -- or are those two merging into a globalized, parametric nowhere-land? I would argue that no matter the aesthetic tone, its realm is one where the client and architect conspire in the context of an increasingly interactive artistic environment -- one that motivates museums, the gaming industry and even tourist-destinations to design themselves with a bit more flexibility and interactivity than before. In the shifting tectonics of architecture, aside from remarkable innovations of design and building technologies, the boundaries of the profession are debated and defended voraciously: what is the architect’s role and purpose, on the city- and global-scale. But identity crises aside, architects and clients must empathize with the users of their projects, and increasingly those users are relating experientially and aesthetically to urban-life as an interactive commodity.

No one goes to Chuck E. Cheese’s for the pizza. This doesn’t assume that everything is defined by the tropes of commercial architecture, but that citizens’ relation to their urban environment is subject to the shift from a service-based to an experience-based economy. Named during the 1990s, the experience economy effectively explains why businesses like Chuck E. Cheese’s exist: they offer a memorable experience as a distinguished and competitive commodity. No one goes to Chuck E. Cheese’s for the pizza. Within the experience-economy, businesses become stages for events, rather than goods or services, and customers are the audience, looking for a memorable experience above all. This could, on a more frightening level, permit the commodification of the actual city-fabric: urban space could become (even more of) a medium for marketing campaigns, and architecture part of a city-wide “brandscaping” strategy. In derogatory terms, this would mean modeling cities after Disneyland, where everything has corporate sponsorship and a coordinated homogeneity. Which isn’t to say Disneyland doesn’t have an incredibly successful architectural landscapes -- only that it’s prohibitively priced, and built at a child’s scale.

Journalist Judith H. Dobrzynski, in a recent op-ed for the New York Times, blames the experience economy for an increase in amusement-park-style museum exhibitions, along with the stress on public institutions to adapt to increasingly technologically-driven (and often hyperactive) social experiences. In her piece for the Times, Build-A-Bear Workshop and even the entire city of Las Vegas are cited as adaptive symptoms of the experience-economy, but evidence of this development within the art world can be found since at least 1996, when Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term “relational aesthetics” to describe the contemporary art scene of the 1990s. Instead of focusing aesthetic interpretation on the art-object, or a scripted performance, “relational art” derives significance from the collective interactions of people sharing an experience. The artwork is then interpreted as a function of these “intersubjective” actions -- relational aesthetics interprets beauty through the expressive network of human society. Architecture can neatly embody both a relational aesthetic and a “stage” for the experience-economy -- defining the style of relations within the architecture can be more problematic.

While initially inspired by the art world’s reaction to the internet-boom’s diversification of human interactions, Bourriaud’s “relational aesthetics” can now be considered, from the cynical standpoint of generations who grew up with the internet, as a sadly outmoded term. In the late 90s, the interconnectivity of the internet was nowhere near as pervasive and rampant as it is today (on our wrists, for instance). Now, it can be hard to specify an aesthetic experience as “relational” when so much of consumer technology's pervasiveness is billed on connectivity and communication-access (and therefore, relationships). A couple years after Bourriaud coined the term, B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore published “Welcome to the Experience Economy” (1998) in the Harvard Business Review, and universities had started responding in kind back in 1994 -- when Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania established the first degree in “Interaction Design”, as a design-centric approach to these perpetually complicating new outlets of experience.

Now, it can be hard to specify an aesthetic experience as “relational” when so much of consumer technology's pervasiveness is billed on connectivity and communication-access Architecture both sits comfortably and fidgets wildly alongside relational aesthetics. On first consideration, architecture could be the ultimate medium of (centuries-)long-form relational aesthetics -- as long as the structure/built-environment is in use, it catalyzes an immensely complex network of human interactions and relationships. Interpreting the term more literally, relational aesthetics dominates workplace design, as an obsessive attempt to preempt serendipitous collaboration that fuels innovation, and ultimately, profit. On second thought, architecture is often built with a specific function in mind, so while individuals are free (hopefully) to interact within the given space, their actions are somewhat circumscribed/limited by etiquette-descriptors like “theater”, “restaurant”, “single-family home”, or “café”, even as ubiquitous computing dissolves these boundaries by releasing certain tasks from a physical job-space. In terms of what people see as art, the point of relational aesthetics was to point the label away from a given object or specific space, and towards a resulting social ether (in Rirkrit Tiravanija’s classic series of relational aesthetics, the artist made thai food for patrons in an otherwise empty gallery, eclipsing the perceived function of the space with the social exchange that occurred among diners, cooks, servers and observers. Much earlier, John Cage’s 4’33” pointed in the same direction.) Architectural aesthetics are both relational and objective (directed towards an object), and do not have the luxury of existing without any prescribed function (unless we’re talking follies, which is a whole other can of worms).

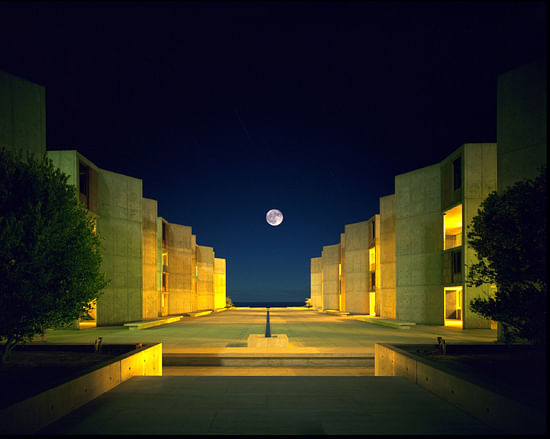

So what does all of this say about the generic user’s interpretation of architecture? Where typology and creativity and business climate manage to fit snuggly together, projects like the Salk Institute merge service-economy and relational aesthetics into a structure that is both empathetic and expertly functional. The Salk Institute, for example, is the product of a client-architect collaboration where science and art had a mutually inspiring relationship, and functionality was clear-cut, as was the user -- far from considering the generic experience-economy seeker, the building could anticipate its particular user-professionals. When the user-type is more general and less predictable, the space may be interpreted through the experience-economy’s lens of services like Foursquare, Twitter, Yelp, Instagram -- where locations are packaged with personal preference, style and experience. This could be in accordance with larger experimentations on crowd-sourced urbanism, but as soon as money enters the equation, the voices of the public don’t always resound in unison. Whatever the architect churns out, and for whatever client, they’ll be hearing from the disparate but loud voices of the masses.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

9 Comments

I enjoyed this article and need to digest it a little more before commenting. But I do want to say that the juxtaposition of the parametric rendering with a party at Chuck E. Cheese just filled me with dread - it encapsulates a whole lot of what I fear about the future of the built environment.

This is a very thought provoking piece.

"it’s harder to quantify why an individual user finds a space remarkably successful, without citing poetics of emotional or intellectual rhapsody. So when considering the “generic” user, how does one relate to the architectural art form, and how should those creating architecture understand that relation?" I think you answer this a bit later with...

"...architects and clients must empathize with the users of their projects,"

Assuming one agrees, how do you teach empathy and what form does it take? For sure it's the opposite of the architect who brings their aesthetic vision to every project. This will unfortunately not sit well with most architects raised on the Ayn Rand version of the hero architect as arbiter of society, but could make more a more humane environment.

As for who's making money from the whole endeavor, there's always someone making a buck so I would just chose with my feet and avoid these packaged experiences you allude to. And if you can't, in other words, if your kid really wants to go to Chucky Cheese, just go and empathize with her.

"Is the dominating aesthetic determinant geography, or technology -- or are those two merging into a globalized, parametric nowhere-land?"

I know you said you weren't an architect, but aesthetic determinants can be infinate or as simple as you say, it all depends on the context and one's own approach to design. This parametric nowhere-land is only the provenance of sites like this and other high style media which like the 1%, constitute thier own culture and society. The other 99% can't afford anything that rich, assuming they like the Jetson's look. Personally, I love those curves in the hands of Gaudi or Saranin's TWA terminal, but when it becomes an extruded plastic shell like a skin on a car chassie, it leaves me somewhat unsatisfied.

As for architecture as an interactive commodity, or stage set as some might say, I think it's only since the Savonarola Modernists went on thier purity crusade that architects have thought we'd be better people living in spartan environments. Fortunatly we have ample evidence from less puritanical quarters of our cultural heratige that tell us differently.

All the world's a stage!

have you been watching the borgias in your free time, thayer?

433 as relational? hate the idea but would concede the point, in a roundabout way. I never noticed relational aesthetics gaining any ground in architectural discourse, seemed an art world thing, once their objects were threaten with disappearing as ours were decades ago. kinda a blurry text to my tired eyes.

is mies Savonarola? hard to buy when looking at the Barcelona pavilion or the tugendhat house. is loos Savonarola? lots of touchy feely sensuousness there too. Corb might have white washed everything, but he's too plastic to be Savonarola. I don't know where your modernism comes from dear Thayer?

I tend to agree with the writer's assertion that "...architects and clients must empathize with the users of their projects". I'm not sure who you hang out with, but I tend to know more non-architects than architects, and most of them have similar views towards modernism. I think it's important to understand these views unless one happens to think that as an architect you are above these mundane considerations. As for sensuous marble slabs, I can appreciate many a kitchen counter-top, it's the rest of the Barcelona Pavilion that leaves me cold, and that's his humanist work. I grant that some percentage of the population will be drawn to spartan modernism as I am at times, but if an architect must empathize with the users of their projects, maybe our built environment would improve.

Hallelujah and Amen, Sister

Thayer-D: thank you for your thoughts. I don't think unique aesthetic styles are at odds with empathy, so an architect can have a distinctive style that still meshes successfully with its users. I settled on the term "empathy" as a still rather general concept, and I do think it's possible for an architect to be both empathetic and challenging/exciting in design. And the tricky thing about empathy is that it may not always look so nice. As you say with "voting with your feet", you may still end up in a Chuck E. Cheese's not in support of its architecture but of your kid. What I find most exciting in designing for empathy is the potential for architecture to be adaptive and physically flexible, in the way that it can interact with both its environment and citizens to better perform overall. So the aesthetic and the materiality may interdependently affect mood.

More on 4D materials

I'm sorry I left the impression that empathetic architecture has a unique aesthetic, but I can see how you got that impression. My issue is more with the seeming disregard of how users tend to relate to the built environment and how it seems to be at odds with how architecture is taught. There is a big disconnect between a lot of the architecture you find on sites like this one and the general public. Your Disney cover image highlights this point. It was designed and built exactly when America's real main streets where being abandoned and demolished in favor of striped malls and office parks, all with a spartan modernist aesthetic. Obviously it's unfair to say that this architecture is more representative of modernism than the best work of Mies etc, and it's likewise unfair to proclaim that no one appreciated the clean lines of mid-century modernism (Madmen). After all, with the space age and the marvels of science improving our daily lives, it's no wonder that many saw the future in this new glass and steel aesthetic. But it's also true that in suburbia, traditional styles still held sway.

And how I was taught to relate to end users was very different than how I practice as an architect. This lack of empathy or better yet, this misaligned set of priorities was established by the early modernists and continues to this day. Again, this should in no way discredit any one aesthetic and modernism in particular, but I think you touched upon something that I found missing in my education, and something I still find missing in a lot of work that get's lauded by the architectural media. Empathy, thinking of how the person who will experience your work vs. how you will be seen by your peers once you release the photoshoped images of your next paradigm shattering object. This is where architecture seems to be misshandeling its responsibility.

Now should we all be "empathetic" architects? Of course not. There's room for all types. But it seems like the baseline should be more geared towards the public who will live with our work vs. the insular world of media/academia that many architects seem to aspire to. Afterall, the "look at me" types will always be able to take care of themselves. It's the quiet ones that need to be encouraged to do their part in improving our environment, whether it challenges us or simply comforts us. Life is plenty challenging as it is. Sometimes architecture simply needs to be a pleasant backdrop for which to play out one's life.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.