Judging by its nicknames, Chicago is a city driven by industry and a competitive mentality, whether matched up against comparable US metropolises or cities abroad. And while it may no longer be regarded as the urban symbol of architectural influence, Chicago has played an undeniably central role in the creation and dissemination of new ideas, inspiring those who passed through (including Adolf Loos and Frank Lloyd Wright) regardless of how long they stayed. A new collection of essays, gathered under the title Chicagoisms, explores the city’s personality and influence on the forefront of architectural progress, setting a new tone for how architects talk about the “Second City.”

Edited by architect and theorist Alexander Eisenschmidt in collaboration with art historian Jonathan Mekinda, both assistant professors at UIC’s School of Architecture, Chicagoisms is the collective thought-pieces of 28 authors, including contributions by Aaron Betsky, Sylvia Lavin, Winy Maas, Stanley Tigerman, Kazys Varnelis, and Sarah Whiting. The essays conceptualize Chicago’s role in architecture and urban development as broadcaster, economic and technological innovator, entrepreneur -- effectively, as an archetype of the industrial metropolis, and a necessary stop-over (temporarily or indefinitely) for anyone who deals in the built environment.

The publication coincides with an exhibition of the same name, on display at the Art Institute of Chicago now through January 4, 2015.

Screen/Print is excerpting a slightly condensed version of the introduction to Chicagoisms; enjoy below.

Introduction: Chicago as Idea

from Chicagoisms

Throughout its relatively short urban history, Chicago has mesmerized people around the world as both a symbol and embodiment of the modern metropolis. This collection of essays takes exactly this power of the city as its subject and explores the influence and impact of the idea of Chicago. Long celebrated as the birthplace of modern architecture in America, Chicago is the subject of a remarkable body of work, both scholarly and popular, exploring the history of architecture and urbanism in the city. Ranging from monographs on the city’s most important inhabitants and events to more methodologically varied explorations of specific building types, local architectural “schools,” and the impact of various social, economic, and natural forces on the growth of the city, most of these works focus on factors internal to the city and its local and regional context. This focus, in turn, reinforces the popular notion that Chicago is a particularly and uniquely American urban formation, a notion that is not only fundamental to the reputation of the city, but also central to the stories that Chicago tells about itself. This conception of the city, however, largely fails to account both for the diverse ways in which outsiders have engaged Chicago and for the tremendous impact that the city has had in other contexts – national and international. Indeed, it appears that the well-rehearsed and widely repeated narrative of Chicago’s architectural development often prevents understanding the city in relationship to other forces.

Rather than celebrating the city’s rootedness in a distinct regional environment, this collection of essays interrogates Chicago’s connectedness to a larger global network of people and institutions, forces and ideas. In particular, it focuses on two aspects of the life of the city that are often overlooked, namely its remarkable power as a transmitter of ideas about the modern city and its particular capacity to foment radical architectural and urban visions. Having served as a source of inspiration and a site of activity for architects, urbanists, and theorists around the globe, Chicago is here examined for its ability to act constructively as a mediator of ideas – an architectural broadcaster of sorts – and as an instigator of speculation – a kind of urban incubator.

Chicago’s engagement with the world performs then in two directions: away from the city, via its activity as an exporter of architectural and urban ideas, and toward it, by offering the city as a test-bed for speculative agendas imported from abroad. Adolf Loos and Frank Lloyd Wright are just two of the many figures who demonstrate how the city operates in these capacities. Loos visited the city in 1893 to see the World’s Columbian Exposition using money his mother only gave him on the condition that he never return home, while Wright abandoned his established life and practice in the city when he left for Europe in 1909. Both acted as carriers of ideas: Loos absorbed the lessons of the so-called “Chicago School” and brought the ideas of Sullivan to Europe, while Wright’s Wasmuth Portfolio linked international modernism forever to the American Mid-west. Eventually, Loos and Wright also returned to Chicago with more radical proposals for the Tribune Tower of 1922 and the National Life Insurance Building in 1924 respectively. For both architects, Chicago not only provided a critical impulse for their excursions – acting as an accelerator to the transmission of their architectural agendas – but also offered solid ground for the projection of their speculative proposals.

Recounting Loos’s and Wright’s relationship with the city offers a preliminary glimpse of Chicago’s power as a springboard for urban and architectural dreams that was rooted in its the well-rehearsed and widely repeated narrative of Chicago’s architectural development often prevents understanding the city in relationship to other forces.commitment to commercial progress, openness to technological experimentation, and willingness to reinvent itself – qualities manifested in such projects as the raising of the city’s ground plane in the 1860s, the reversing of the Chicago River in the 1890s, and the almost constant expansion of the city on landfill during the 1910s and 1920s. It was precisely these kinds of projects that, along with its unprecedented pace of growth (from a frontier village to the sixth-largest city in the world in only seven decades), made Chicago one of the most widely celebrated and most frequently visited examples of the industrial metropolis. Some visitors remained in the city permanently, most just stayed briefly, and others only “visited” with the help of media such as postcards, photographs, and movies. All of them, however, were eager to find in Chicago the future that still lay ahead for most cities.

Indeed, the imaginative capacity of the city is such that Chicago has inspired projects elsewhere that were not even considered possible at home. Hans Hollein, for example, spent much of the year he lived in Chicago during the late 1950s re-imagining the famous tall buildings of the city, first embracing and then re-deploying the conventions of the type. His “Skyscraper of the Future” project from that year split the conventional tower into segments to accommodate gardens and public spaces and other programs in the air. After more than fifty years in Hollein’s sketchbook – preserved and ready for resuscitation – the scheme is currently under construction in Shenzhen, China. This is just one instance of the actualization of Loos’s assertion about his own Tribune Tower proposal: “It must be built! If not in Chicago, then in some other town.”

Chicagoisms, the title of this volume, refers precisely to those moments of productive interaction and wild provocation, of radical speculation and fruitful exchange, that Chicago is uniquely capable of inspiring, fostering, and implementing – a power well demonstrated by the sheer number of proposals that take the city as a launch-pad for urban and architectural imaginings. In the Chicagoisms considered here, selective episodes in the history of the city are interrogated with the explicit aim of shedding light on the internal workings, dynamics, and forces that have made Chicago such a site of possibility. To that end, this volume brings together two types of studies: on the one hand essays that explore particular figures, ideas, and events, and on the other hand shorter, more speculative commentaries on a number of the city’s best-known projects. The distinction between these two components is not simply a matter of scale, but also of orientation: while most of the essays look at the city from the outside-in, the commentaries inserted between them proceed from the inside-out to address the works’ broader influences and capacities. Drawing on both new research and new readings of already familiar projects, this collection aims to break open the conventional and hermetic narrative of Chicago’s architecture and urbanism to reveal a condition that resonates in different cities, fields, and practices.

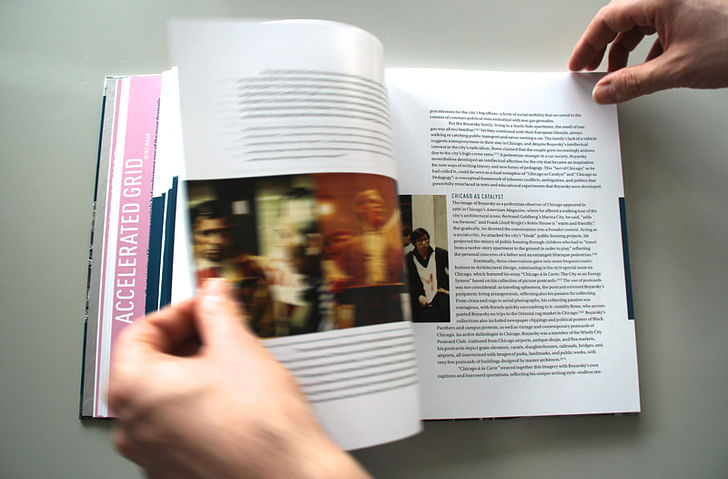

The opening essays by Penelope Dean and Igor Marjanović revisit events of the 1960s and 1970s that profoundly influenced the architectural discourse of the late twentieth century. For Dean, two exhibitions presented concurrently in 1976 demonstrate the stagnation of the established history of Chicago’s architecture and, simultaneously, enable her to unearth alternative legacies within that history. Marjanović focuses on events of a different nature in his examination of Alvin Boyarsky’s tenure at the University of Illinois at Chicago during the tumultuous years of the late 1960s. He shows how Boyarsky’s embrace of the vitality and dynamism of the city, rather than its architectural traditions, inspired his subsequent activity as the Director of the Architectural Association in London, where he revolutionized the organization of the school and, ultimately, shaped contemporary avant-garde practices through his work with figures such as Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas, and Bernard Tschumi.

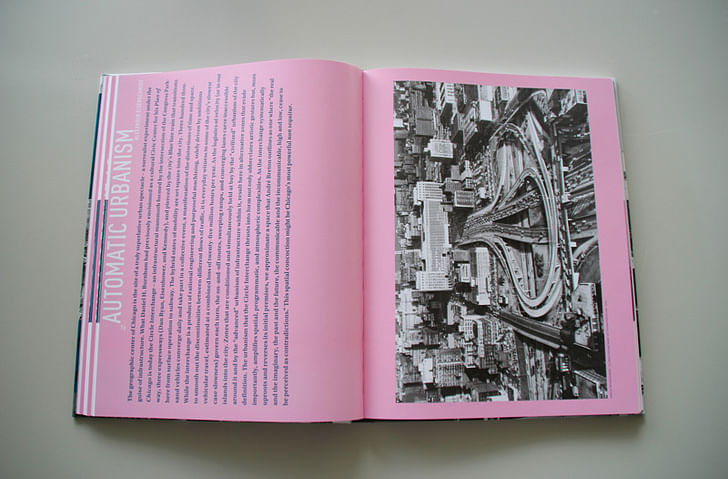

If the essays by Dean and Marjanović highlight Chicago’s capacity to shape architectural discourse and reorganize conceptions of the city, the following essays by John Harwood, Mark Linder, and Albert Pope all take up specific design projects. Pope’s study of the urban project of Ludwig Hilberseimer suggests a deep investment in Chicago’s existing suburban environment, which Hilberseimer brought in line with the gridiron. The modern city visions that Hilberseimer drew up in Germany before arriving in the US found in Chicago a new foil that consolidated previously opposing urban environments (the dense center vs. the distributed suburb). What Pope describes here is a kind of super-urbanism, highly productive for contemporary practice in our time of extreme urbanization. Mark Linder’s text takes us from the Chicago of Hilberseimer and Mies to the England of Reyner Banham and Allison and Peter Smithson, uncovering the intersecting lines between New Brutalism and the Chicago Modernism of Mies van der Rohe. Ultimately, Linder constructs a new genealogy that makes us rethink both movements and exposes unknown, even exotic, tendencies within each. Another colleague of Mies and Hilberseimer at the Illinois Institute of Technology is at the center of John Harwood’s essay, which focuses on Konrad Wachsmann’s ventures into early digital experiments and its possible effects on architecture. Harwood suggests that these proto-computational models were the first attempts to calibrate architecture around research principles and cybernetics, practices that would only gain substantial currency much later.

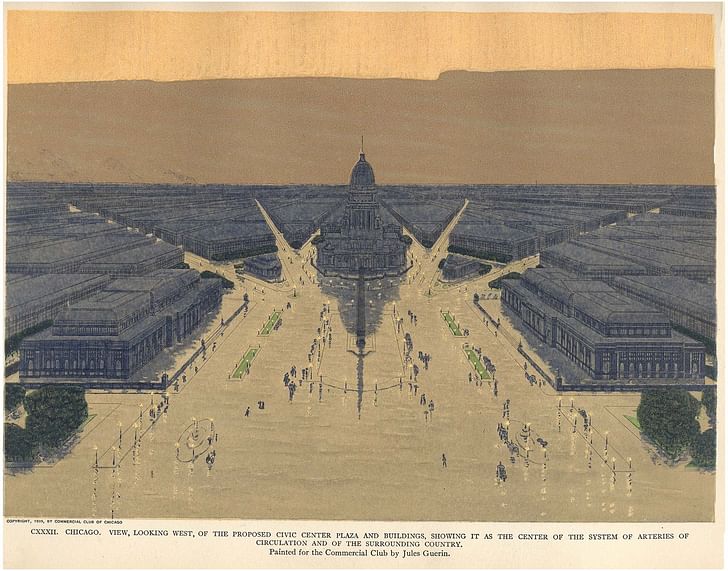

In the final set of essays, Joanna Merwood-Salisbury, David Haney, and Alexander Eisenschmidt consider earlier aspects of Chicago’s architecture and urbanism, particularly in relationship to the city’s reception elsewhere. Merwood-Salisbury’s analysis of the “Early Modern Architecture: Chicago 1870–1910” exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1933 explores what she describes as a process of “naturalization” through which the modern architecture of Europe was stripped of any association with radical politics and rooted instead in American capitalism. With this transformation, Chicago became a key accomplice in the creation of the myth of the “International Style.” Like the “Chicago School,” celebrated by Hitchcock and Johnson, Daniel Burnham’s Plan of Chicago (1909) is another of the city’s famous “urban legends.” Focusing on the travels of the plan across Europe in the wake of its publication, Haney examines its reception in London, Paris, and Berlin, where it functioned as an industrious piece of architectural propaganda. As this essay shows, it was impossible to talk about the state of the city at the turn of the twentieth The object here is ... to open up a new discussion about the potentials generated by the city itself.century without referring to Chicago. But even before Burnham’s Plan, Chicago had become for many cities abroad the measure of urban modernity. The final essay considers how the city became the model through which Berlin was able to understand its own rapid urbanization during the late nineteenth century and, ultimately, reconceive itself as a space of possibilities for the invention of a metropolitan architecture.

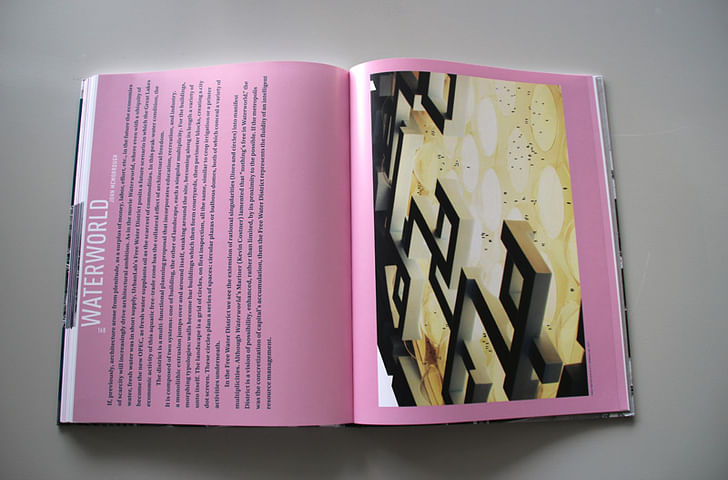

The essays gathered here stray from the well-trodden paths of Chicago’s history to explore lesser known episodes and a wider range of actors and objects, from architects to exhibitions, from books to punch cards. The object here is not to give yet another summation of Chicago’s history, but to open up a new discussion about the potentials generated by the city itself. In order to amplify the multiplicity of readings afforded by Chicago and its various “isms,” short pieces of writing that comment on specific projects are inserted between the essays. Forming a quasi-independent catalogue of projects, the commentaries articulate an alternative structure, parallel to the essays, that aims to re-situate a number of Chicago’s already well-known works within the particular framework of this collection.

Together, the essays and commentaries gathered in this collection probe the extent of Chicago’s capacity to spark the imaginations of architects and engineers, artists and urbanists, and to foster the spread and cross-fertilization of ideas about the modern city. This approach to the city as an idea – as an intellectual concept as much as a physical phenomenon – does not overturn or substantially alter the established history of Chicago so much as it supplements and complicates that history. As the various episodes and projects considered here show, the idea of Chicago was both powerful and adaptable, serving as a harbinger of architectural and urban worlds to come and spurring a remarkable range of actions and activities far beyond the city as well as within it. In the light of these “Chicagoisms,” the city no longer stands as only an American formation, but must been seen within an international discourse about the industrial and later post-industrial city and the architecture appropriate for it. By virtue of its status as an iconic modern metropolis, with all of the horrors and dreams associated with it, Chicago profoundly shaped – and was shaped by – that discourse.

The tension between the “positive” and “negative” aspects of modernity that Chicago has so clearly displayed to the world since the early nineteenth century is paralleled by another tension no less fundamental to the way that the city has developed: that between the demand for action and the desire for refinement. Many of the city’s most famous projects resulted from efforts to engage problems of the modern world through the most efficient and straightforward means possible, often resulting in radical formations of urbanism and architecture. Others, in contrast, were motivated by the desire to repair, if not counteract, exactly that pragmatic impulse and its “ugly” consequences. From the vantage point of today, however, it seems clear that Chicago’s maturing has brought an increased caution toward its previous restlessness and ambition to extrapolate modern conditions. Taking this observation seriously, this collection not only aims to trace the characteristics, attitudes, and mentalities that made Chicago and mesmerized other cities, but also hopes to channel a renewed boldness to engage the city’s history as well as today’s urbanized world in general. To counter the increased caution of the city, perhaps what is needed is a move from “Chicagoisms” to “Chicagoism,” that is the extraction from the episodes considered here of a more abstract but widely applicable theorem or principle of action that recognizes and engages the city as a catalyst. “Chicagoism,” then, would emphasize the operative function of the city as a construct that is effective beyond the city’s bounds, providing the ground for experimentation and releasing ideas into the urban and architectural ether.

Who's behind Chicagoisms:

Contributions by:

Chicagoisms is available to purchase here.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured Chicagoisms.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

1 Comment

ragged right is, well, raggedy. widows and orphans galore. who did this page layout? it is not good.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.