The American suburbs no longer exist as physically and conceptually peripheral to the downtown, the central consciousness of urban development. According to Judith K. De Jong’s new book, New SubUrbanisms, the suburbs' mainstream designation as places of seclusion, domesticity, superficiality, and safety (set in comparison to their accompanying denser urban downtowns), has collapsed in the wake of a feedback loop between central city and suburbia.

New SubUrbanisms questions this stubborn dichotomous stereotype, and proposes a hybridized version of the two that could unveil hidden innovation. To De Jong, it’s not as if one typology is overruling the other, but that each archetype has begun to imitate the other. This relatively recent phenomenon is both caused by and provokes a retooling of the suburban/urban model, where an unsustainable typology has to adapt to pressing standards of density, transportation and affordability.

De Jong herself is no stranger to suburbia — previously her proposal “How the Strip Mall Can Save Suburbia” was a finalist in the 2010 Build A Better Burb competition. She’s currently a practicing architect and assistant professor in architecture at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

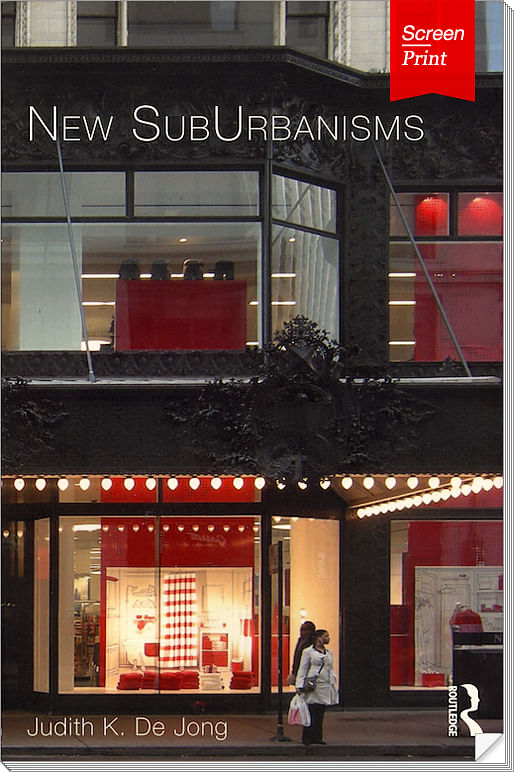

For Screen/Print, we've excerpted the introduction and beginning of New SubUrbanisms.

During the suburban explosion of the mid-20th century, the typical American city and its suburbs seemed to reflect distinctly different cultural, demographic, and spatial conditions. The central city was conventionally portrayed as the old, dying locus of high culture and employment, demographic diversity, density, and verticality, while peripheral areas were stereotyped as new, growing residential enclaves of mass culture (ergo, cultural vacuity), homogeneity, dispersion, and horizontality. This polarization has proven stubbornly resistant to revision.

Meanwhile–quietly, stealthily–there has been an ongoing “flattening” of the American metropolis, as many suburbs are becoming more similar to their central cities, and cities more similar to their suburbs. Such flattening is both effect and cause; driven by substantial demographic and cultural change and evidenced by new spatial and formal practices, flattening also makes architectural and urban innovation possible. These novel practices, seen most vividly in urbanizing suburbs and suburbanizing urban cores, are exemplified in the emergence of hybrid suburban/urban—sub/urban, for short—conditions: interstitial parking, the residential densification of suburbia, inner-city big-box retail, and hyper-programmed public spaces, among others. Each of these new sub/urbanisms reflects, to varying degrees, the reciprocating influences of the urban and the suburban. At the same time, these hybrid practices combine and re-configure conventional understandings of these familiar terms. In so doing, each offers opportunities for design innovation and the development of new ways of forming the evolving American metropolis.

Flattening: Literal and Conceptual

The paradigm of flattening has two strands—the literal and the conceptual—that encompass primary yet divergent processes of suburbanization. Many metropolitan areas show varying degrees of both trajectories, but it is conceptual flattening that provides the most significant opportunities for the development of new ways of forming the evolving American metropolis.

The pastoral trajectory of suburbanization is a literal form of flattening; this trajectory derives from the suburban villa and its relationship to nature, and is exemplified in the narrative of the middle landscape. As advances in transportation technologies allowed people to live individual sub/urban projects and in-between sub/urban areas present the moments of most potentialfurther away from their work, the form of the city was quite literally becoming physically flat as the periphery began to expand, particularly in those cities with the flat, seemingly limitless geographies of much of the United States. This trajectory was most pronounced in the explosion of post-World War Two American residential suburbia, comprised largely of single-family houses on individual lots, producing a middle landscape with an ever-increasing perception of space. It was also evident in the parallel evacuation of the failing inner city, as buildings were razed for parking and empty lots proliferated, also producing a reading of void. Carried to its logical extreme, this literal form of flattening continues today in the so-called “shrinking city” phenomenon, exemplified by Flint, Michigan, and Youngstown, Ohio, where extensive population loss has resulted in an ongoing erasure of the inner city at the same time as the periphery continues to spread.

However, when not used in reference to a literal, physical condition, the terms flat, flatness, and flattening are frequently used more conceptually to indicate homogeneity, often pejoratively. In All That Is Solid Melts Into Air (1982), Marshall Berman uses flattening to indicate a lessening of substance when he laments the “steril[ity]” of modern cities and modern life as “a dismal flattening out of social thought.” In SuburbiaNation (2004), Robert Bueka uses flattening to describe a lessening of difference and the rise of homogeneity when he says “the suburbs may well be flattening the landscape of America, fostering homogeneity of experience through the ‘displacement’ of place itself.” Perhaps the term’s most widely known use—although it is not pejorative—is in The World Is Flat (2005), where Thomas Friedman uses flatness to articulate a shrinking, globalizing world characterized by equality of power and opportunity: “[T]he simple notion of flatness…describe[s] how more people can plug, play, compete, connect, and collaborate with more equal power than ever before” (italics mine). In each example, regardless of the discipline and the tone of the argument, increasing similarity is a conceptual characteristic of flattening.

As such, the alternative trajectory of sub/urbanization is a conceptual form of flattening, defined by an increasing similarity between urban and suburban forms and ways of life. This trajectory recuperates and updates a largely overlooked narrative of the suburbanization of work and the transformative development that it often engendered, much of which was a nascent hybrid between urban and suburban. Importantly, this trajectory also incorporates a different kind of suburbanization of the inner city, most evident since the 1960s, whereby suburban influences are hybridized with the urban to produce more interesting and instrumental forms, such as the mutating big box store and hyper-programmed public spaces. An ongoing, often asymmetrical process, today’s conceptual flattening is manifested most vividly in the demographic and cultural trajectories, as well as in the spatial and formal practices, of urbanizing suburbs and suburbanizing cities. Perhaps counter-intuitively, the increasing similarity that characterizes conceptual flattening does not ultimately produce a fully level physical condition, nor does it equate to an automatic and insistent homogeneity. Rather, conceptual flattening produces greater differentiation as the contemporary metropolitan landscape becomes more urban in some places and more suburban in other places. In this way, flattening is neither post-urban nor post-suburban; rather, it is both urban and suburban. As a result, flattening produces opportunities for innovation in new formal and spatial practices that rearrange the traditional tropes of urban and suburban.

Flattening: Formal and Spatial Practices

The ongoing flattening of the American metropolis is increasingly visible through the proliferation of hybrid sub/urban practices, four of which are particularly representative and influential: car space, domestic space, public space, and retail space. Each of these practices not only evinces new forms from reciprocating urban and suburban influences, but for the city, flattening through suburbanization is not the formal and spatial death sentence it might once have beenalso provides a key point of departure for the articulation of new ways of forming the evolving American metropolis. Thus it becomes clear that for the city, flattening through suburbanization is not the formal and spatial death sentence it might once have been, as new forms emerge that transform suburban influences in denser environments. Meanwhile, for the suburbs, flattening through urbanization recuperates a long and largely overlooked history of the suburbanization of work–and the hybridized conditions it often engendered–more recently maturing and materializing through new, hybrid forms of architecture and urbanism. While some individual sub/urban projects display design promise and innovation, many do not. In addition, the aggregated conditions that result from flattening are often clumsy and seemingly in-considered, and their persistent “in-betweenness” causes great consternation among urbanists. Importantly, both individual sub/urban projects and in-between sub/urban areas also present the moments of most potential, as they not only challenge preconceptions of what it means to be urban–or suburban–but also open up new conversations and possibilities regarding the present and future of the rapidly changing American metropolis.

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured Judith K. De Jong's New SubUrbanisms.

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

1 Comment

The author seems to proclaim as breaking news the complex connectivity of central & peripheral parts of metropolitan regions. (It hasn't been "quiet" or "stealthy.")

This isn't new. Joel Garreau wrote about it twenty years ago in Edge City, and it wasn't new even then. Scholars such as Herbert Gans, Sam Warner, Olivier Zunz, Thomas Sugrue, Richard Longstreth, Paul Groth, Greg Hise and others have been working for decades now with the premise of a metropolitan system in which the urban/suburban binary is less and less meaningful.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.