Scenario Journal pools fresh, collaborative conversations on urbanism from design and the sciences, focused on rethinking urban landscape performance. Metamorphosing from its previous incarnation as the Landscape Urbanism Journal, the journal builds on the theoretical foundation of "landscape urbanism," which emerged from the backlash against both modernist urban planning and New Urbanism. It champions landscape manipulation as the core organizational system of successful contemporary urban environments — a move away from objectified buildings as the currency of a thriving urban space.

Scenario Journal mixes submissions by artists, practitioners, academics, and students from design and the sciences to tease out what Landscape Urbanism can mean for today’s developing cities. The journal's name comes from scenario planning, a strategic forecasting method where ideas are played out through theoretical future scenarios and war games. Taking this approach to urban planning, Scenario’s content aims to help city-makers understand and anticipate the remarkable complexities that future cities stand to offer.

From Scenario’s fourth issue, “Building the Urban Forest”, Screen/Print is featuring “To Multiply or Subdivide: Futures of a Modern Urban Woodland”, by Jill Desimini, an assistant professor of Landscape Architecture at Harvard’s GSD. Desimini’s research focuses on revitalization of abandoned spaces in shrinking cities, turning voids into places of productivity. Her piece for Scenario Journal focuses on the potentials of the plot of land in St. Louis, Missouri where the infamous Pruitt-Igoe housing complex used to stand.

"To Multiply or Subdivide: Futures of a Modern Urban Woodland"

By Jill Desimini

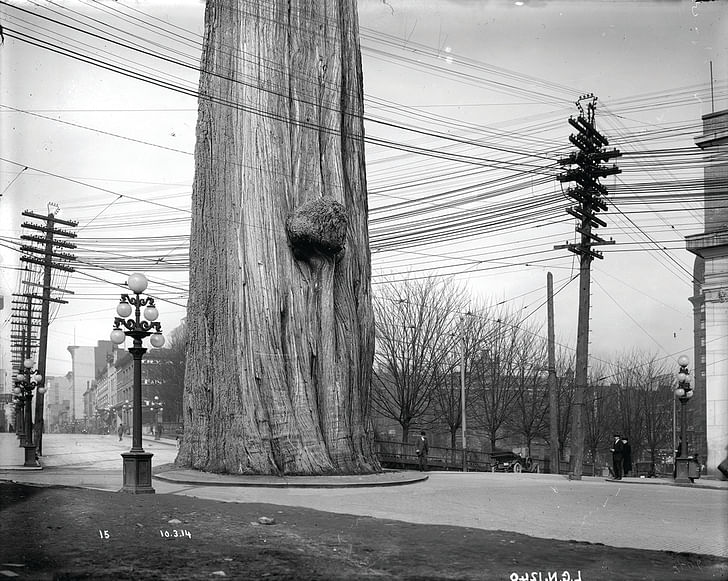

In America, the forests of our past stretched across the continent, in wide bands, with distinct species marking the different longitudes and latitudes of the vast territory. Surveyors had to devise new systems of measurement to address the wooded landscape—the European precedent only worked for a denuded terrain with vast open views. The American forest was dense and occluded, unmatched in its richness and diversity. The famed naturalist John Muir described them as the best that God ever planted [2]. The transect was impressive from the eastern spruce-fir and the beech-maple-birch forests of the northeast to the loblolly pinelands of the southeast through oak forests and aspen-birch tracts, to the dry ponderosa pines and the deciduous conifer larches onward to the immense western hardwood forests and the coastal lands of Douglas fir, Sitka spruce and redwoods.

These trees, as decried by Muir, gave way to urban progress with its agricultural fields, cityscapes, infrastructural projects and industry. But as the cycles dictate, the forests are re-emerging, as spontaneous woodlands on abandoned farms, foreclosed subdivisions, vacant parcels, un-mown right-of-ways and former factory sites. As landscape architect Gilles Clément indicates, these are the forests of the future, the sites to be targeted, re-invented and claimed as the next commons.

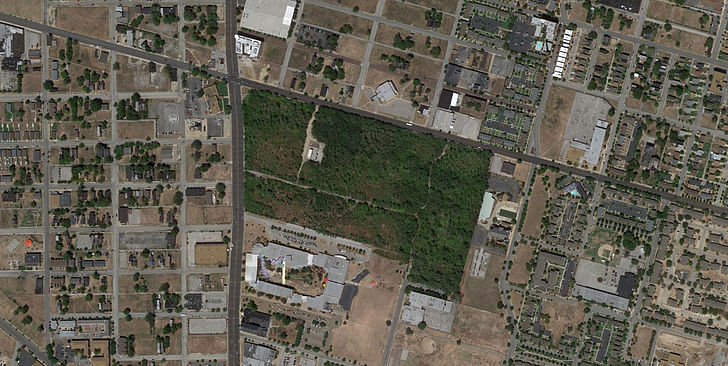

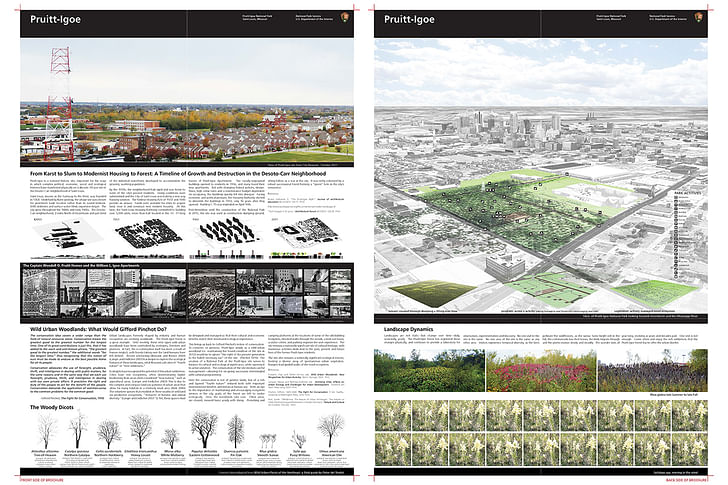

One such tract—a 33-acre parcel—sits less than one mile from downtown Saint Louis. The site is stunning, both from a distance and on the ground. To penetrate the overgrown perimeter (the fence is a key element in the ecological toolbox, collecting seeds, protecting seedlings and fostering incredible spontaneous plant growth), is to discover a magical interior. Trees loom over forgotten streets with occasional street lamps and manhole covers Any future development should respect the resilient, both the human and the floral and faunal.signaling former development. Rolling topography, formed from the dumping of construction waste, supports varied vegetal communities—a testament to the idea that complex, urban land use patterns yield high biodiversity [3]. Perfect sumac domes have found their ideal home and the site has attracted a suite of species capable of both thriving in the harsh environment and contributing ecosystem and aesthetic benefit.

The place is remarkable both for its present constitution and past legacy. Once the home of the infamous modernist public housing project—the Captain Wendell O. Pruitt Homes and the William L. Igoe Apartments—the contested site has remained in limbo since their demolition, long enough to grow into a substantial wild urban woodland [4]. Yet, after forty years, the tower demolition imagery remains the most well-known and proliferated symbol of The decision as to what to un-build is as fundamental as what to build.the site [5], while the burgeoning forest is unrecognized, overlooked as a resource worth mentioning, much less celebrating or conserving. […]

Post-demolition, the site sat unused, with high levels of debt and social stigma discouraging development but welcoming floral and faunal invaders. It was used as a construction dumping ground, taking much of the material from the stadiums and the convention center, but otherwise sitting fallow as a scar in the city. In the early 1990s, 57 acres were given to the construction of the Gateway school complex. The site was capped, with a large berm burying the toxins below. The remaining 33 acres continue to be richly colonized by a robust successional forest forming a “green hole” in the city’s conscience.

The unique circumstances surrounding the Pruitt-Igoe site have protected it from development, especially the often seen transition from modernist public housing towers to HOPE VI style suburban enclave. This transformation can be seen on the adjacent site. However, after forty years, the pressure seems more imminent. A local suburban developer, Paul McKee, known for his corporate campuses on greenfield sites, has targeted the neighborhood for his next project, Northside Regeneration. He has purchased over 2,220 parcels in the surrounding neighborhoods, including an option on the Pruitt-Igoe site [6]. The project has garnered political support, but the vision remains nebulous. There is no question that the area is in need, as one of the hardest hit areas of population and economic loss, and McKee’s emphasis has been on job creation. Yet, he is treating the land as vacant, as a brownfield tabula rasa akin to his greenfield sites, disregarding past use, and Cities have rich ecosystems, often demonstrating higher biodiversity than areas often considered “near-natural,” such as agricultural areas.present occupation. It is true that many have left the neighborhood, but those who have remained have chosen to do so. Any future development should respect the resilient, both the human and the floral and faunal. […]

Ecologists have recognized the potential of the wild urban woodlands. Cities have rich ecosystems, often demonstrating higher biodiversity than areas often considered “near-natural,” such as agricultural areas [9]. This is due to the complex and compact land use patterns of urban areas that allow for many habitats in a relatively small area [10]. The volunteer species that establish in these swaths of woodland are productive ecosystems, “‘hotspots’ of botanic and animal diversity.” [11] These spaces of newfound environmental significance—dubbed novel ecosystems [12]—are the contribution of the anthropocene. The forests of our future are hybrid spaces, rich and layered biomes shaped directly and indirectly by human activity. Their design and management must address ecological, as well as cultural and economic requirements. It is time for urban designers to join their ecological cohort in championing the successional urban forest as an important element in urban restructuring. The insertion builds on past landscape infrastructures, large tracts of land like the Forest Parks or the 1,100 acre Emerald Necklace in Boston, set aside as civic amenities. It recognizes both the need to adopt former sites of human occupation as the next fodder for conservation and the impetus to restore balance to the urban environment. The successional urban forest recycles land and provides breathing room in formerly dense conurbations with species well-adapted to the given conditions.

The tools of design are twofold: one at the regional or city-wide scale and one at the site level. The existing and potential forested tracts must be identified, drawn and configured to form the backbone of future development. They must be set aside, acquired much in the same way early conservation pushed the creation of America’s National Parks. The decision as to what to un-build is as fundamental as what to build. Conserved forests may become one element in a larger citywide development strategy that addresses the full complexity of issues facing cities losing population. Then, at the site scale, the forests require greater interpretation. They cannot be simply conserved as ecological preserves or held to an idealized pre-human nature, which National Parks at times foolishly attempt. The latter is counter to the very definition of the novel ecosystem while the former would ignore Gifford Pinchot’s key notion of conservation. To conserve, or preserve, Pruitt-Igoe and analogous sites simply as wild urban woodlands would be to ignore “the right of the present generation to the fullest necessary use” of the sites themselves [13]. Instead, the woodland conservation demands careful management—allowing for on-going succession intermingled with cultural programming. […]

Designed experimental landscapes afford the chance to vary the extent of intervention, with some areas left to continue unabated growth, others arrested in states of incomplete succession and still others design for active human use [14]. The strategies evoke those used in early American parks, with sheep grazing and visitors ambling, but the presentation is direct, with a contemporary view of the ecological and cultural landscape as slowly evolving, dynamic space meant to reconcile past occupation with present demands. Resources are limited and they must be understood, respected, conserved, and adapted rather than wiped clean for the next wave of short-sighted subdivisions. The nascent forests emerge from the overgrown vines and scrubby trees. Inside there is enchantment awaiting discovery.

This version of “To Multiply or Subdivide” has been slightly condensed. The full version (with complete footnotes) can be read here.

Also featured in "Building the Urban Forest", which can be read in full here:

Screen/Print is an experiment in translation across media, featuring a close-up digital look at printed architectural writing. Divorcing content from the physical page, the series lends a new perspective to nuanced architectural thought.

For this issue, we featured Scenario Journal's "Building the Urban Forest".

Do you run an architectural publication? If you’d like to submit a piece of writing to Screen/Print, please send us a message.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.