This past spring I was honored and deeply grateful to be named the 2013 graduate level recipient of the Steedman Summer Traveling Fellowship.

Awarded annually to two students of architecture, in Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis (one graduate student one undergraduate student), the fellowship supports summer travel and investigation of an architectural topic of the student's choosing. Recipients are selected by the Steedman Fellowship Governing Committee on the basis of their proposed study outline, portfolio of work, and academic achievement, and must present their research to the student body in the fall.

I am spending the summer in China to investigate, document, and research traditional Chinese urban communities. Focusing specifically on the Hutongs in Beijing and the Longtangs of Shanghai, my analysis revolves around the complex tension between these neighborhoods and the current state of Chinese development.

For the month of June, I am based in Beijing. I am staying with my brother (who has been working in China for the past six years), and his wife, a Chinese native. Through their contacts, I am in touch with a variety of local architecture offices and preservation groups to help me along the way.

In July, I head south to Shanghai, where I will link up with my urban design colleagues from Sam Fox (including my partner in crime, Jennifer Wong). They are spending the summer with one of our school's many abroad options, the Global Urbanism Studio. Once there, I will take advantage of the resources available from their host institution, Tongji University, and glean as much information as possible.

I give a special thanks to the Tibet Heritage Fund for the vast wealth of information from their Beijing Historic City Study.

Few countries offer such drastic juxtapositions of ancient and contemporary landscapes than China, and the contrast in housing is no exception. China is experiencing unprecedented urbanization. If the current trends continue, China will have added 350 million people to its cities in 20 years, more than the entire population of the United States. This growth has already had enormous consequences on the existing fabric of its cities; as China struggles to keep up with the realities of growth, it has demolished entire neighborhoods and communities that have long-standing history and a culture of life that is rooted in hundreds of years.

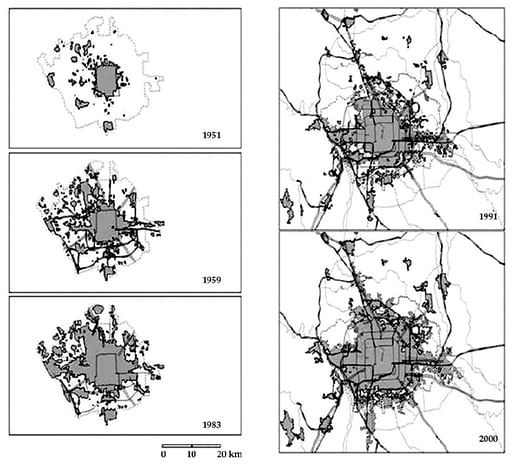

Currently with over 20 million residents, Beijing has experienced a nearly 700% increase in population over the last 60 years.

Image taken from: Wang, 2003, Pg 30-31, British Experiences

Beijing is a city of contradictions

I arrived to Beijing just over twelve days ago. In that time I have found my bearings in the city, identified my target study area, and laid the foundations of my research. Jennifer Wong was able to join me for six days in the first week. Everyday brings new discovery and observation of the urban life between buildings (including a chance encounter with Steven Holl). It is a city whose history dates back 3,000 years, nestled on a flat plane and cradled by small mountains to the northwest. It is a city with an existing built-fabric of over 800 years, with a thorough sprinkling of glitzy and iconic interventions that I have seen again and again on the covers of architectural magazines and the lectures of my professors throughout the long and demanding road of becoming an architect. It is unlike anywhere that I have ever experienced. The diversity is overwhelming, and so is this endeavor to describe it.

This is the first installment to report back on my fellowship: The first impressions of Beijing through my eyes and hands.

of Ancient Walls

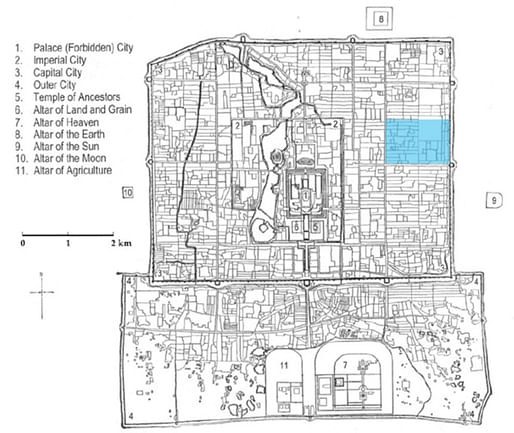

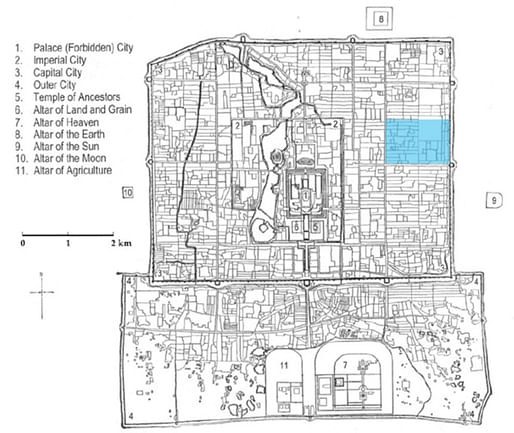

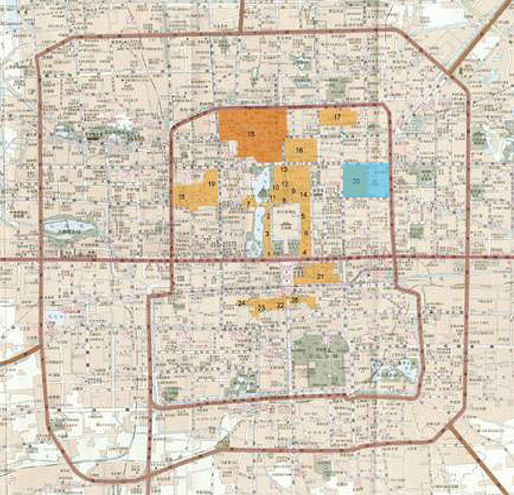

Beijing Old-Town, 1553-1750, the blue highlight represents my area of focus.

Liu, 1980, pg 280, British Experiences

The historic center of Beijing as we know it today exists from a 13th-Century plan laid by Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis Kahn and the founder of the Yuan Dynasty. Ancient Chinese urban planning principles from the Chun Qui period (770-476 BC) called for a palace in the center of a rectangular street grid. Surrounding the palace would be a series of temples, markets, and city walls. These same principles were taken and adopted as the city expanded into the Qing Dynasty (1664-1911). The historic center runs along a 7.8km north-south axis.

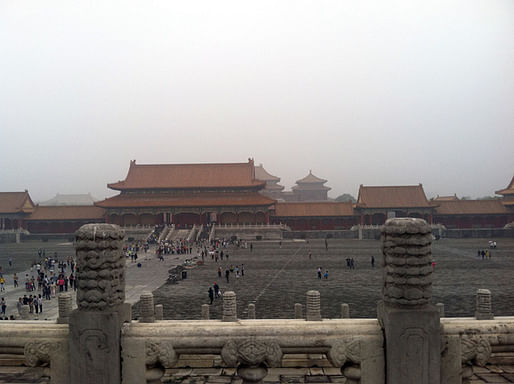

Forbidden City (Imperial Palace) as seen on axis from the temple atop of Coal HIll, an artificial hillside built of rubble for Feng Shui purposes to block evil spirits from the north. This may look like a foggy day, but don't be fooled; it is pollution. My first week in Beijing we experienced particularly bad pollution for Beijing standards.

Inside the Imperial Palace one experiences a series of hierarchical walls, gates, and moats that envelope processional and ceremonial courtyards. These very principles reciprocate out into the city at a reducing scale.

The most central point of the historic city.

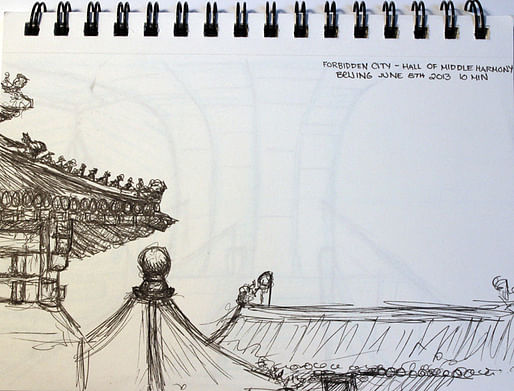

Sketch by Jennifer Wong My sketch of the central halls.

My sketch of the central halls.  Every structure is carefully aligned along a strict north-south axis.

Every structure is carefully aligned along a strict north-south axis.  Beijing was laid out with several natural and artificial lakes and waterways, creating careful barriers to separate recreational areas and temples from other city functions.

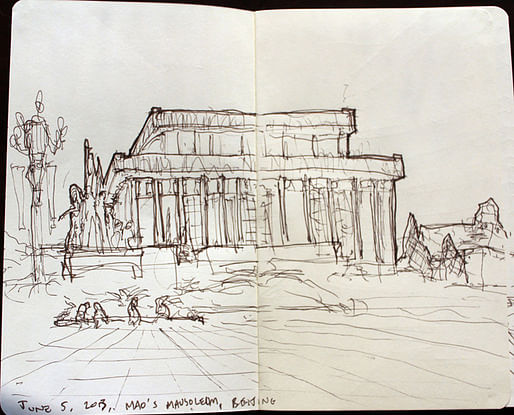

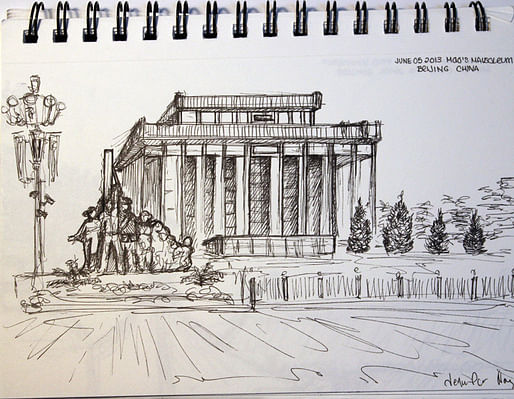

Beijing was laid out with several natural and artificial lakes and waterways, creating careful barriers to separate recreational areas and temples from other city functions. Mao's Mausoleum, the focal point in Tian'an Men Square, is surrounded by a series of gates and planted barriers, physically divides the enormous plaza.

Mao's Mausoleum, the focal point in Tian'an Men Square, is surrounded by a series of gates and planted barriers, physically divides the enormous plaza.

Mao's Mausoleum through the eyes of Jennifer Wong

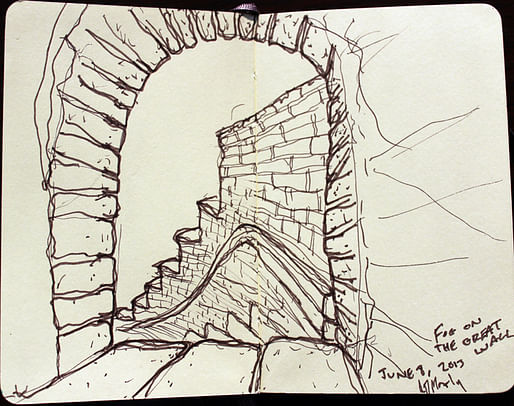

A portion of the Great Wall of China lies just 40 minutes north of Beijing. Beijing's city walls were demolished in the middle of the 20th Century and replaced with the second of a series of concentric ring roads as part of the 1958 Beijing City Construction Master Plan.

Disappearing into clouds.

Sinuous curves of the wall

Sketch by Jennifer Wong

Stone vaulting inside one of the watch towers

This photograph helps to grasp just how steep the wall got at some points. The photos do not do it justice.

The Marble Carriageway - The central ramp the Hall of Supreme Harmony in the Forbidden City is carved out of a single stone and was solely reserved for the Emperor.

Winding Paths in Coal Hill Many of the ramps from Imperial times are ingeniously designed with stone and brick work that tapers up to create high traction.

Many of the ramps from Imperial times are ingeniously designed with stone and brick work that tapers up to create high traction.

of Winding Walkways

City plans from the Yuan Dynasty called for 3 street typologies:

1. Primary north-south axis roads (37.2m wide)

2. Secondary roads that also run east-west (18.6m wide)

3. Hutong Lanes, which mostly run east-west (9.3m wide)

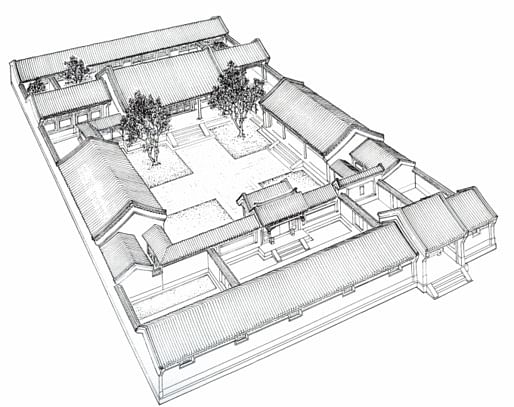

Typical layout of a traditional siheyuan

Hutong Lanes made up the large majority of the inner quadrangles and were traditionally organized about rows of siheyuan, the quintessential chinese courtyard house. Siheyuan were essentially small microcosms of the larger palaces; they sit on a north-south axis, with the entry gate (Dao Zuo Fang) located on the southern side with the main building (Zheng Fang) placed along the north. Two side buildings on the east and west (Xiang Feng) create a fully enclosed and secluded courtyard retreat from the city. Intended for a single family, the siheyuan followed a strict building code of uniformity in both color, ornament, height, and design during the imperial times. The higher the status of a family, the larger the courtyard home was allowed to be. It was thought that no single residence in Beijing should have walls or structure that rose higher than the Forbidden City.

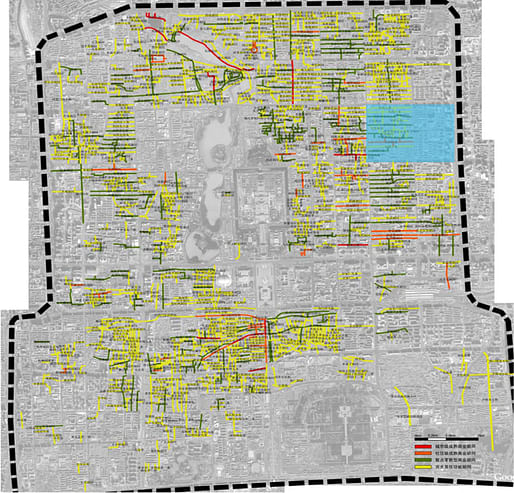

Existing Network of Hutongs in historic Beijing.

Credit: Yang YANG, School of Architecture, Tsinghua University, Beijing, P.R.China

The entries through gates and into the Courtyards of the Imperial Palace are larger scaled versions of the siheyuan entries.

Entry Dao Zuo Fang of a subdivided siheyuan.

20th Century Informalization

After the fall of the Qing dynasty (1912), the strict rules governing the use and design of siheyuan and the hierarchy in relation to the imperial building code loosened. Residents began to modify or reconstruct the original buildings. The Cultural Revolution and the social reforms that began in the 1950's compounded this change in the hutong structure when the courtyards and homes were subdivided for multiple families. Further subdivision was made in the 1970's after the Tangshan earthquake left thousands of residents homeless. Over this period, the hutongs took on a new character as many residents began to add on informal extensions to the courtyards. In many cases, a siheyuan is only recognizable from the outside, and any resemblance of the original interior is all but gone. The reduced living quarters and interior courtyard spaces have had large implications for the alleys themselves; more and more the hutong has become the extension of the home and taken on a role of public communal space that bustles with activity.

This does not come without problems, however. For the sake of this post I will address issues of ownership and management in a future entry, but many of the hutong communities are severely lacking in adequate utilities, healthy heating systems, and are at risk of living in unsanitary conditions and precariously structured informal additions.

I will get into this more specifically in future posts ownership and management

There is a rich variety of Hutong Alleyways. Along every main east-west hutong spurns a smaller, north-south, and sometimes snaking tributary alley. These sub alleys are generally more narrow, and quiet.

This Hutong, Dongsi Liutiao, is wider than most, and the presence of car traffic disrupts the peacefulness of the experience. A pleasant stroll turns into a stressful and weave in and out of cars.

The bustling markets along Hutong Dongsi Sitiao. Too narrow for cars, and so congested with pedestrians that cyclists must dismount and walk their bikes. Street life is at full force here.

Many of the Hutongs are undergoing major renovations, and construction materials are left along the sides of the alleys, creating more congestion.

Workers making their way home at the end of the day. I trailed this group of about 12 workers to see that they all live in the same Siheyuan. It is likely that this is an example of "Work Unit Housing," in which a government company or institution, and sometimes a private company, will provide free or subsidized housing for the workers. The living conditions in these units tend to be in much better condition than public housing.

A very narrow side alley off a Hutong. Note the informal use of materials.

One of the poorer neighborhoods I have been through. I did not find one major remnant of an existing Siheyuan in here, and it almost all appeared to be informally planned and constructed.

More construction in the Hutong

During the evening and nights are my favorite times to explore the hutongs. The alleys transform in character under a red glow from the main commercial strips and the siheyuan windows. Residents keep their doors open and old men sit out in the street playing card games and board games until late in the evening.

Balcony addition to a proper Siheyuan structure.

Roof Guardians are found at the ends of the gables - they are associated with water and meant to protect the homes against fire.

Ridge Detail

Exquisite hand-carved detail in the entry frieze.

In few instances people have built additions on a second floor. Imperial building code allowed for 6m height with the gable, so it is technically possible to get two floors within the hutong datum.

Markets

Hard at work.

Fresh cuts off the street.

Hang it out for dinner.

Mmmmm! The ones on the left did not look so hot.

Fresh Street Produce

The city center's waste management system operates with a fleet of bike carts that deliver garbage to a compressor/treatment center in the street.

Many hutong alleyways literally become the residents' living room.

Every square inch of available space is gobbled up - building out an informal wall.

I was surprised with the large number of police stations located in the alleys.

A larger police station with an attempt to tack on a traditional entry.

One of the biggest issues with the hutongs is the lack of adequate plumbing. Almost all courtyards have at least one shared water tap, but most residents do not have bathrooms. As such, there is a vast network of public toilets throughout the hutongs. Some have shower facilities but not all.

For the most part, these facilities are severely overused, and are generally not connected to any sewage system, but drained by pump trucks. Particularly in the summer, this creates serious issues of hygene in the communities.

In some cases the living spaces for residents is extremely tight, with many neighborhoods averaging only 5 square meters of living space per resident, well below the Chinese "modest wealth" standard of 12 square meters per person.

The most common structural building problems are rot in the timber roofs, chiefly due to a lack of maintenance, allowing rot to creep in from little ventilation.

In some of the biggest examples of informal settlement, I found old objects and discarded belongings thrown onto the rooftops to weigh down the corrugated metal roofs.

Beijing Rising

China's Economic Liberalization of the 1980's rapidly stimulated the economy with a particular boom in the property market. China implemented what is known as the "Weigai" system as a method to relocate residents from dilapidated housing, tear down the old structures and redevelop the property. The Weigai system gave property developers total freedom for redevelopment without any regard to conservation, the only condition being that they rehouse the inhabitants to the adequate 12 square meter "modest wealth" metric.

Out with the old, in with the new.

Developers' strategy was generally to relocate the residents to areas far outside of the city, where the land is cheapest, making it more difficult for workers to commute to their jobs in the city center, and adding more pressure and pollution to an overworked traffic system. Those who were rehoused in the original site often found themselves with less square footage of living space than they previously had because they had no courtyards in the new developments. Between 1990 and 2000 alone, roughly 200,000 families were relocated by the Weigai system, and more than 4 million square meters of Hutong neighborhoods have disappeared.

The demolition of these neighborhoods continues today, although thanks to a recent rise in local activism and awareness groups, 25 historic and cultural protection zones were designated in old Beijing in 2005. The future of these is still uncertain, as there is weak oversight in regulation and vague management structures as to who is responsible for which tasks.

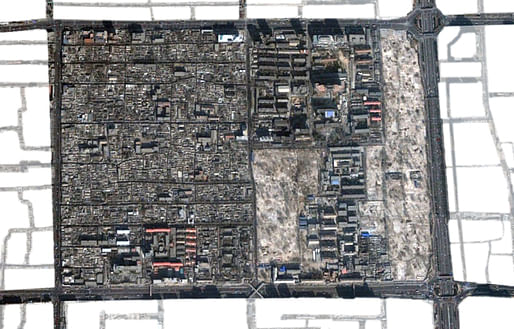

My specific area of focus is in the quadrant of the Dongsi South Sub-district. Half of the quadrant falls inside one of the designated cultural protection zones (it was slated for demolition by Weigai in the 1993 plan), and the other half experienced a massive demolition and redevelopment in the past ten years. My brother (and host) happen to live in one of these new residential developments, and I find myself right in the middle of the quadrant. On one side: ten hutong alleys with a variety of functions and varied states of repair. On the other side: medium-rise, redeveloped housing that gives into high rise banks and skyscrapers.

Credit: Yang YANG, School of Architecture, Tsinghua University, Beijing, P.R.China

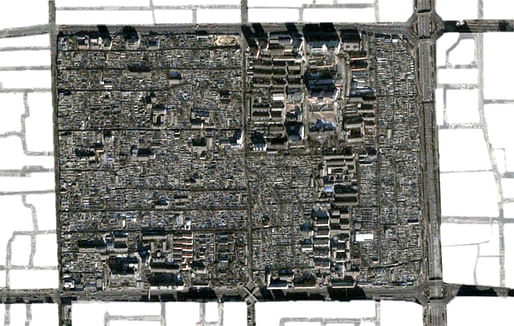

Dongsi South Sub-district, January 28, 2001

Large swaths on the east side of the quadrant still retain the low-rise hutong alleys.

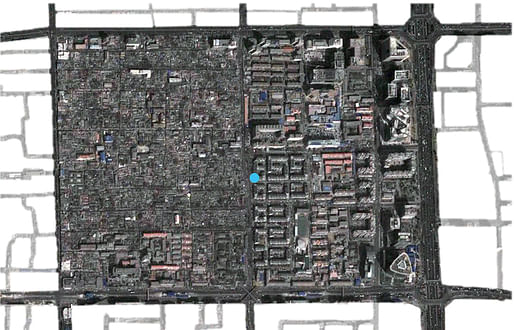

Dongsi South Sub-district, February 11, 2002

In one sweep of the hand, nearly all hutongs on the east side of Dongsi South are demolished to the ground in the period of one year.

Dongsi South Sub-district, March 29, 2012

Today, the entire east side is redeveloped with new housing towers and commercial high-rises. The blue dot indicates my apartment in Beijing.

Panorama from my brother's terrace looking southeast; to the left - all new development in the past ten years. To the right, the remaining 10 hutongs of Dongsi South.

The view from the internal courtyard of my brother's apartment. While not as dense, and certainly with its own problems, the complex retains certain communal benefits with a clear hierarchy of pedestrian streets and common spaces. There is absolutely still a vibrant community here. I will be analyzing this in contrast with the hutongs in much more detail soon.

Difference in spatial scales looking north up Dongsi Beidajie, the central secondary artery the divides Dongsi South between hutongs and redevelopment.

Another jump in scale from medium rise to high rise.

Beijing Rising

Nevertheless, the juxtapositions between old and new in Beijing are astounding.

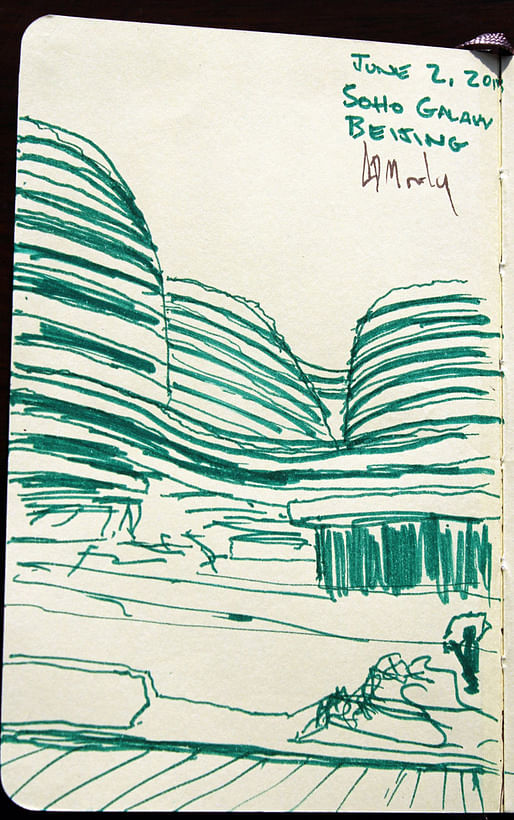

Peaking up over the past: Zaha Hadid's recently "opened" Galaxy Soho - a shopping mall on the lower levels with office space on the upper floors. It opened last fall and still does not have any tenants as far as we could tell as we walked through.

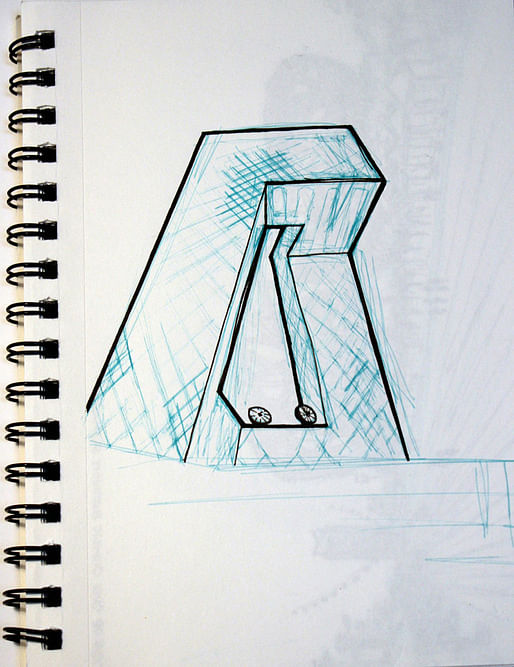

Quick sketch of exterior

With classic Zaha flair, the internal courtyard achieves incredible and moving dynamism, and while the mall was empty of tenants and shopping, this public space was actually being used by people old and young. Mother's were letting the kids play in the fountains.

Every vantage point afforded a new and stimulating view.

Interior lobby to the office entry

Elevator lobby

Detail of the rail glass gradient pattern.

We were disappointed, however, with the overall details up close. For a building that is less than a year old, there were already stains in the paneling (why white in such a polluted city!?) The craftsmanship on all details was a bit shoddy, stressed at all the seams, and at times unacceptably sloppy. Note the glass planel towards the back of this image - it is put in upside down.

Particularly the landscape design/craftsmanship... so many messy details, that we worried were never going to be resolved.

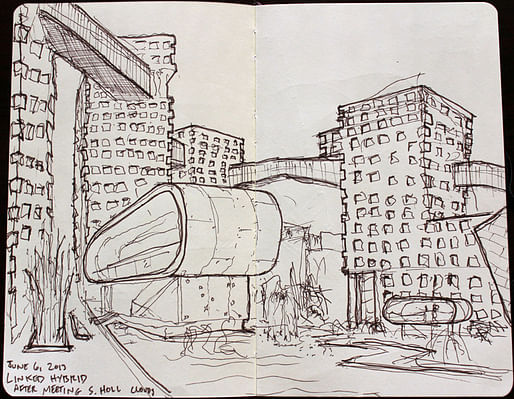

Perhaps the most ominous of the high-profile developments we saw from afar was Steven Holl's Linked Hybrid. Rising like a monster out of the demolished mud.

Contrasts of the old and new.

Like Zaha's Galaxy, the internal space was a much more pleasant experience, and we appreciated the fact that the courtyard was open to the public.

Below the apartment towers was a variety of mixed-use services from a restaurant to a supermarket, to a gallery, to a movie theater. The bridges helped to create a great sense of enclosure and the large regular window openings brought down the scale so that it did not feel nearly as large and inhuman as it appeared from the outside. The seemingly arbitrary rotations of the towers gave it a bit more playfulness and helped avoid the static feel of his Simmons Hall at MIT.

Not long after we arrived, who comes walking through? Steven Holl! He was giving his brother a tour of the building. We introduced ourselves briefly and he apologized for the lack of sunlight. A very pleasant coincidence.

Steven Holl looking out over this design.

Detailing of the paneling and a custom door handle - memories of Finland.

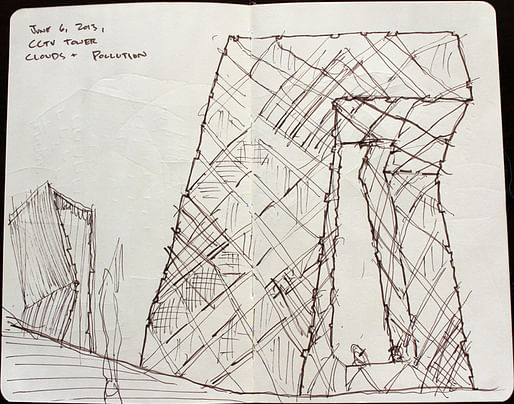

The CCTV Tower would have taken the cake for most ominous had it only been surrounded byt recently demolished swaths like the Linked Hybrid.

Rising out of the earth and into the pollution.

In terms of its urban qualities, this was by far one of the worst. The entire building was gated off with no public access even close to it.

Sketch by Jennifer Wong

Apparently lots of locals refer to it as the "Pants" building.

The BTCC - back in 2008 this thing caught fire and has been sitting vacant and empty like a corpse. Supposedly they cannot take it down because it serves as a structural counterweight to the CCTV Tower.

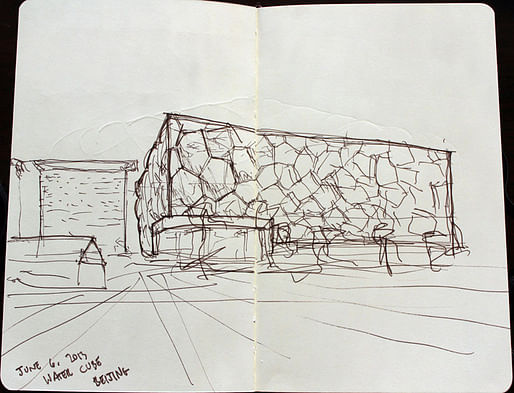

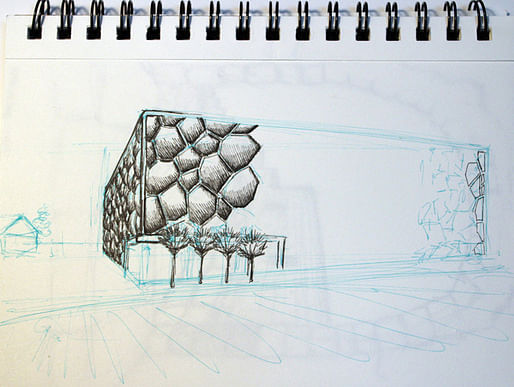

Arup's Watercube

Sketch by Jennifer Wong

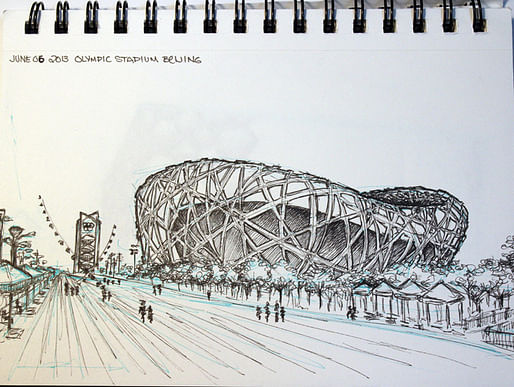

The Bird's Nest Stadium

Nearly everywhere we sketched, and wherever I have sketched since Jennifer left, curious people come flooding over and are fully fascinated. Throughout all of Europe and South America, I've never seen passersby be so curious about sketching.

Jennifer Sketching the Bird's Nest.

Sketch by Jennifer Wong

We were very disappointed with how the building has aged.

Light detail around Bird's Nest.

Is the only solution for Beijing?

Is this the new winding walkway?

Demolition of many structures in the hutong will be inevitable and necessary.

There are other ways to rebuild and reinterpret.

Traditional reconstruction

Laying new brick

Despite a lack of assurance in land security (this example is not in a cultural protected zone), people are still rebuilding in large numbers.

A contemporary composition with traditional materials

A restaurant using the same grey brick of the neighborhood for a nice window detail.

This was perhaps the most interesting, an unassuming building at a corner.

At closer glance, it reveals very delicate details.

We chanced upon the family eating dinner in the hutong - front door wide open. If anybody knows who the architect of this is, please let me know! I looked and could not find.

The grey brick of the hutongs.

Until next time, thanks for reading!

This work by Alexander Morley is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

A new adventure begins as we finish one chapter; we hope to share our story with you. We are graduates of Washington University in St. Louis, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts.

9 Comments

Great Travels and wonderful sketches....

what a visual feast, thanks for sharing. Wonderful sketches too.

Thanks!

Great post. I live in beijing and still much of this is interesting and new for me to hear haha. I suppose I should read more about where I live. I used to live near there actually (at dongsisantiao). Something I did not realize until I lived in the hutongs and talked to coworkers and friends who had grown up in them is how controversial they are amongst the locals. For many people (usually non-architects) who grew up in the overcrowded conditions without any privacy whatsoever, they are not necessarily sad to see them bulldozed to provide better housing. Winter is also a totally untenable situation in most of the buildings, where the interior temperature will be only slightly above what is outside.

There are also plenty of people for whom the forced relocation was a tragic event for the family, but overall it is a much tougher debate then is often made out in western publications on the subject. To return the area to its "proper" historical state is to return it to very low density, high wealth dwellings, which has its own set of social problems, and would at this point be pure reconstruction in most areas. You really "can't go home again". Anyways have fun in beijing!

nice work!

ps i live at the same blue dot!

cheers for the tour. very interesting. look forward to reading future posts.

Excellent post, really enjoyable and great pics! Thank you for sharing it!

There is a movie called Raise the Red Lantern set in a 1920s courtyard house. The building figures large in the film, which is beautifully filmed.

Ancient Chinese urban planning? Excellent post! You were awarded the fellowship in 2013. Your resume indicates you have been working at Ferguson & Shamamian Architects, LLP in New York since 2014. Were you able to apply your experience in Beijing to any projects you worked on for this firm? Please share.

Ancient Chinese urban planning? Excellent post!

You were awarded the fellowship in 2013. Your resume indicates you have been working at Ferguson & Shamamian Architects, LLP in New York since 2014. Were you able to apply your experience in Beijing to any projects you worked on for this firm? Please share.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.