Berlin wall memorial, by Kohlhoff and Kohlhoff Architects. Photo by Chris DeHenzel.

Berlin wall memorial, by Kohlhoff and Kohlhoff Architects. Photo by Chris DeHenzel.

What comes to mind when you think of Berlin? Other than music from Top Gun, of course, you may have more or less vivid memories of the GDR, the wall, electronic music, guys (and girls) with arm sleeves and black mohawks, empty warehouses full of experimental art – and if you’re an architect, maybe also the Reichstag, Jewish museum, or the proliferation of informal urban installations. What probably doesn’t stand out is the food. According to Nikolaus Driesen, co-founder of Markthalle Neun, that’s because the city of Berlin doesn’t have much of an established food culture. Or, at least it's been a while.

Collage from http://www.markthalle9.de/

Collage from http://www.markthalle9.de/

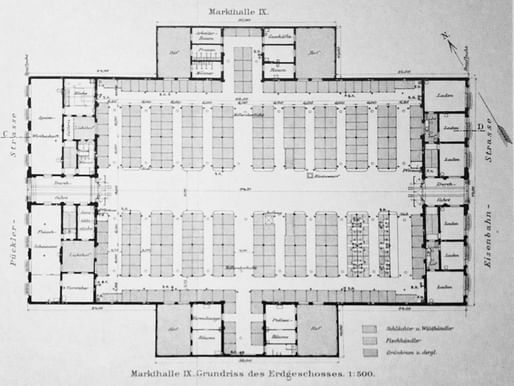

Markhalle Neun is a new market concept in an old market building, one of 14 market halls that were constructed in Berlin during the late 19th century. Built in 1891, it is one of only four halls left remaining after WWII, but it hasn’t been used as a public market since the war.

Historic map of Berlin Food Markets, courtesy of Markthalle Neun

Historic map of Berlin Food Markets, courtesy of Markthalle Neun

Drawings and images of the original hall, built in 1891, courtesy of Markthalle Neun,.

Drawings and images of the original hall, built in 1891, courtesy of Markthalle Neun,.

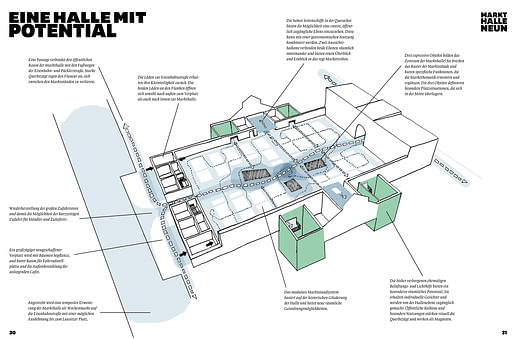

Driesen and his colleagues, Florian Niedermeier and Bernd Maier, who Driesen refers to as “the food guys”, initiated a public protest to prevent a corporate supermarket from moving into the space in 2006, and then convinced the city government that it should be revived as a new public food market, independent vendors and all. There was an open competition for ideas, and in collaboration with badass Berlin-based designers, raumlabor, Markthalle Neun was born, again.

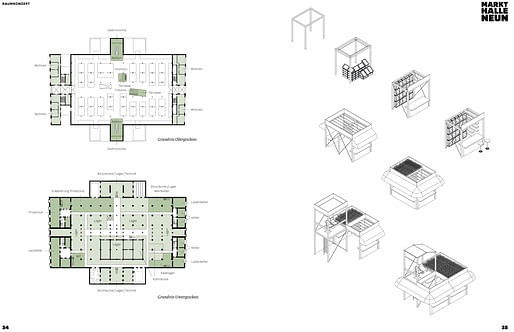

Drawings and diagrams by raumlabor for Markthalle Neun.

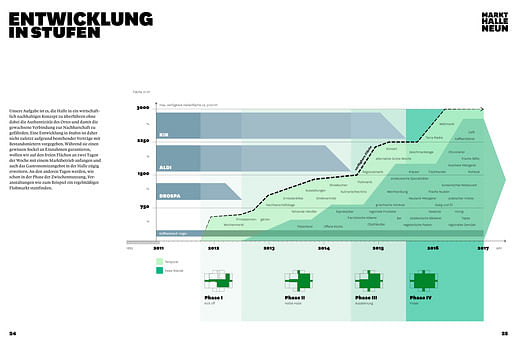

“We opened the market last October”, Driesen described, “120 years after it was first opened. Our idea is to have a real farmers market here, which is difficult because Berlin is not Italy or California, or even Southern Germany. But there are a lot of creative new farmers and food producers from different backgrounds who have started working around Berlin again, and there are more and more people interested in local food.”

Since the culture and economy of regional food has declined in Berlin, like many European and American cities, there is no longer a network of markets. Of the 14 original halls, there is only one other used as a public food market. Without a physical system to connect with, and without a sustained culture of regional production and consumers interested in local food, Markthalle Neun is basically a one-man-wolfpack (to borrow a term from my friend, Ileana Acevedo). “Our concept is to go step by step”, he continued, “and start with what we have. We’re currently only open twice a week because there aren’t enough people in the neighborhood who are willing to shop at a farmers market.”

Phasing diagram, courtesy of Markthalle Neun.

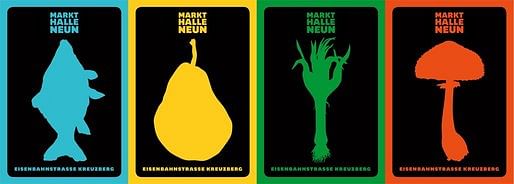

Markthalle Neun isn’t just a ‘revival’. They have new ideas about what the market should be, in its current time and place. What they are attempting is more of a reinvention, with the aim of turning Markthalle Neun into the gastronomic hub of Berlin, pointing to London’s upscale Borough Market as a reference, and promoting a new culture of regional cuisine using the Slow Food model. Despite concerted efforts to promote the market through events, publications, and a sophisticated branding identity, however, “slow” at Markhalle Neun could also be a description for how business is going.

Branding graphics by Markthalle Neun

Branding graphics by Markthalle Neun

I spent nearly a whole day at Markhalle Neun on my visit to Berlin this summer, meeting with the founders and touring the recently opened facility. The market building itself is one of the more spectacular 19th century structures I have seen, but it’s location in the neighborhood is less than ideal, tucked away on a side street in the middle of a residential block. Without a cached map on my iphone, I may not have even found it, despite written directions. Apparently the old real-estate adage (location, location, location) has had more of a detrimental effect to the project than the founders anticipated. “I would have expected that after one year the spaces would all be rented out and the space would be over-crowded”, Nikolaus said. “I should have brought in an expert years ago”. By “expert” he was referring to me. Yikes. All of a sudden, our conversation switched course, from casually discussing the history of the market to a more serious, business-consulting strategy session.

“Tell me”, he queried, “What are the lessons we can learn from what you’ve been doing? I mean, if you were to look at our place, what needs to be changed?”

Gulp. I looked around. It was a Saturday afternoon in July, one of just two days that the market is open during the week, but there was a noticeable lack of activity. It seemed more like the end of a market day than the middle of it. The vendor spaces were only about half-full and there were a handful of happy, white, food-conscious Berliners milling around. Then I told him, in all seriousness, that the market needed a hairdresser and some Turkish vendors.

You should have seen his face. He stared back at me with mixture of confusion and comic disbelief, as if he had just seen a donkey riding in the back of a pickup down a busy urban street.* Ok, I wasn’t completely serious, but I couldn’t help notice the contrast between the street life of the neighborhood and the interior of the market. Markhalle Neun is in Kreuzberg, one of the most ethnically diverse and poorest areas of Berlin, but also one of the most lively, artistic and energetic. Driesen and his colleagues have been living there for many years. They are represented their neighborhood, but they are only representing one small part of it.

“Yeah, the whole gentrification thing is something we have to cope with”, he said, his tone sincere, but strained, “which I think we do quite well actually. Our goal will be to have a particular special place, so that it attracts people from all over the city, which is the only way for us to survive economically. We don’t just want to be a market, we want to be a market place, a political and cultural place, and a place where all the discussion about food takes place.“

Main hall of Markthalle Neun. Photo by Chris DeHenzel

Main hall of Markthalle Neun. Photo by Chris DeHenzel

Shopper coming from the Aldi discounter, to the right, with the main hall in the background. Photo by Chris DeHenzel.

Shopper coming from the Aldi discounter, to the right, with the main hall in the background. Photo by Chris DeHenzel.

Markthalle Neun wants to be a destination market. Perhaps this is different from the classification of “festival market” that I described in my first post, way back last December. A destination market may still be a simulacrum of an ‘authentic market’, but despite appealing to tourists, would be predominantly local. But they do want to be exclusive. Not a neighborhood market with a hairdresser, spice vendors, and affordable produce; but a spectacle, a weekend market. My question is whether or not it could be both. Because they need the neighborhood, whether or not the neighborhood needs them.

One of the reasons why the farmers markets in the United States tend to be so limited from a distribution perspective is that they tend to be very strict about the types of farmers or vendors that are allowed in the market (they can only come from 100 miles away, everything has to be organic, if you don’t grow it, you can’t sell it…etc), and from what I’ve seen, the more diversity in vendors that you have, the more attractive the market will be to all different types of people.

“You need it to be a neighborhood market to allow it to function every day”, I reiterated to Driesen, “but you also want it to function as a destination market, for the ideology of what a market can be, as more than just a commercial space.”

“And I think there are two types of people that will come”, he replied, almost on board now, “one, the people who are interested in where we can get the best food from the best vendors; and two, the people who are interested in the experience of an authentic market, and to have an authentic market you need the local people, otherwise it’s just a tourist thing. That’s our problem right now. We’re too small to attract people from outside the neighborhood, and we’re too expensive to attract people from within the neighborhood.”

I asked him if he knew where people in the neighborhood currently shop for basic groceries.

“At the discounter”, he replied, using the German-in-English way of referring to cheap grocers. There are three small discounters inside the market. They were there before Markthalle Neun took over, and they will remain until the market fills its vending capacity. “Germans spend very little on food. We were the ones who invented discounters. We spend less on food than any other European country.” He’s right about that. But they still spend almost double what Americans do.

Global Food Spending Map, by Natalie Jones. For the interactive version, click here!

Thanks for reading!

* I've seen it, but I can't prove it.

I am a graduate M.Arch/MLA student at UC Berkeley, and grateful recipient of the 2011-2012 John K. Branner Fellowship, an annual traveling fellowship awarded by the UC Berkeley Department of Architecture. I will spend the 2012 calendar year visiting public food markets in major cities on 5 continents to research the relationship between markets and the infrastructure of food systems, focusing on the cultural and urban design implications of local economies. This blog will follow my journey...

2 Comments

Chris, do you have another link to your images and diagrams? It would be great to see them larger! Nice work.

Unfortunately the archinect blog format imports images at a super low resolution and doesn't allow the viewer to click to enlarge. Maybe they're working on this? I don't know. I'll have my own website up before the end of the year, where you will be able to see everything in better resolution. In the mean time, check out my flickr page, here: http://www.flickr.com/photos/snap_crackle_pop/

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.