You may ask yourself, among other things, why we need another blog about food? What might compel you to continue reading, when you already know damn well how to make a fluffy quiche, and you are less swayed by one person’s opinion than the egalitarian democracy of Yelp? Fear not, because this is not just another blog about food, but a way to think about food as infrastructure that defines and is reciprocally defined by urban development. To keep it interesting for a broader audience, I also promise to pepper the content, eh hum, with various other media, travel notes, exotic recipes, maps, diagrams, and the occasional (potentially) humerous anecdote.

Something about me

My name is Chris DeHenzel. I was born (my mother swears “induced”, so that the doctor wouldn’t miss a minute of the game) during half-time of Super Bowl Sunday, in 1982. Later that year Time Magazine would name “The Computer” the person of the year. My biggest fear, as a toddling explorer in rural Minnesota, was getting lost in a cornfield. My family’s move to the suburbs of DC, when I was 4, could have been shocking, but we found a relatively isolated housing development amidst sheep and tobacco farms in eastern Prince George’s County, with plenty of forests and streams for climbing and frog-hunting. I suppose I didn’t realize my own hypocrisy as I bemoaned the increasing suburban sprawl from my cookie-cutter bedroom, but when greedy developers started shooting sheep to terrorize our neighboring farmer, right and wrong seemed fairly black and white. Sometimes, like when cops beat unarmed students with metal truncheons, it still does…

This will not, however, be a blog about clear distinctions and straight answers, although I do intend to report with no-bullshit honesty about what I see and how I see it. I am now a graduate M.Arch/MLA student at UC Berkeley, a place well-known for its integration of cultural and political theory with design, as well as being an epicenter of “The Local Food Movement” (perhaps not coincidentally). I am a grateful recipient of the 2011-2012 John K. Branner Fellowship (along with Marcy Monroe and Nathan John), a travel grant awarded annually by the Department of Architecture at UC Berkeley. The fellowship affords a year of independent research directed towards an M.Arch thesis project. My proposal, titled “Stocking the City: The Architecture and Infrastructure of Public Food Markets” will examine the relationship between the physical structure of markets and food distribution systems globally, in order to propose a more resilient local connection between networks of production and consumption in the San Francisco Bay Area. I will use this blog as a sounding board (and hopefully, a discursive platform) for my background research and on-site investigations, as I investigate the opportunities and paradoxes of public markets around the world.

For interested readers or prospective applicants, you can view my Branner application and portfolio on Issuu.com

Some context

Of the essential infrastructural systems that support cities, (including water, energy, communication, transportation, and waste services) food systems not only combine many elements of the other systems, but also connect to cultural and economic processes. Pierre Belanger, Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, stated in recent interview, “[Food production and agriculture] are the fundamental infrastructures that hold cultures together and sustain (or cease) the longevity of regions. These are spatial, they provide sustenance and form an ecology that generates exchanges, markets, and economies.”(1) He goes on to argue for a more integrated strategy of comingled urban and agricultural land uses, connecting this spatial organization with the potential for social and economic change. I agree with the complex social, ecological and economic ideals behind urban agriculture, and so do a lot of people, like former San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom, who in signed an executive directive to support urban agriculture projects within municipal limits in 2009. As my UC Berkeley professor, Nicholas deMonchaux once joked, “It’s like apple pie. Everybody loves it.” But like deMonchaux (okay, maybe thanks to him), I am more interested in the complications and complexities of urban farming than the wholesale Martha Stewart endorsement of it.

In my opinion, Work AC’s 2008 Public Farm (PF1) project at PS1 in Queens (and following book, titled Above the Pavement, The Farm) was phenomenal in its combined scope, both inventively engineered and socially aware. Meredith TenHoor wrote an essay for the book titled, “The Architect’s Farm”, which (along with Nicola Twilley’s “Edible Geography” blog and Carolyn Steel’s book, Hungry City) has substantially inspired my thesis. TenHoor argues that a paradigm of opposing conditions prevail in the discussion of urban agriculture: on one side a distributed, networked, activist-led, communal “horizontal” organic garden and an industrial, high-tech, iconic, vertical farm. She suggests that the Work AC project at PS1 may be neither traditionally horizontal or vertical, but “oblique”. She writes, “Unlike massive, high-tech vertical farms, PF1 seems to point out that urban space can also support small-scale farms that generate communities around the production of food.”(2)

PF1 rendering by WorkAC, on publicfarm1.org

Pie in the Sky

Nevertheless, vertical farm projects are all the rage, and heavily promoted by Columbia University Professor of Microbiology, Dickson Despommier, in his book, The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century. According to Despommier, “High tech greenhouse farming is already being deployed in many places around the world, most notably in New Zealand, the Netherlands, Germany, England, Australia, Canada and the United States. ... The only missing element is the urbanization of the concept.”(3) There is a utopian zeal to the book, that, while well intentioned, neglects so many issues that it would require a whole other book to dispute it. A 2010 article in The Economist attempts to answer one rather practical question, “Would it really work?”(4) The embodied energy of food production is a complex issue that remains contested, and there may also be no significant advantage to locating a vertical farm in a central business district compared to a less densely built area of the city. But beyond the logistical and economic problems, the social implications of productive urban towers seem unfortunately modernist. The quasi-Archigram charm of the concept, imagining it in reality conjures more Ville Contemporaine than anyone might be comfortable with. Despommier’s proposal relies heavily on the assumption that transportation accounts for the majority of the system’s ecological impact, although a May 2010 report by the USDA report, titled “Local Food Systems”, suggests otherwise. According to the report, “Comparisons of local food systems to food sourced from mainstream retailers found no significant differences in transportation energy use, except for those products transported by air. The shorter distance traveled in local markets was offset by the greater transportation efficiency of the mainstream system, which lowered energy use per unit transported.”(5) Don’t get me wrong here. I’m not reading a USDA “research publication” as if it’s completely reliable (I have seen “Food, Inc”, etc, and read various accusations about corporate influence at the USDA), but the basic point remains valid. When discussing components of a system, one needs to consider the broad range of factors, frameworks both physical and institutional, that define it. Which brings me to a fundamental point: The “designer obsession” with production has neglected a close scrutiny of distribution models.

The question should not just be, “How do we integrate production in cities?” But also, “How do we reorganize infrastructural systems (especially distribution models) to support more alternative forms of production?”

Vertical Farm, rendering by atelier soa

Public Values: Public Markets

Therefore, I will focus my research on public urban markets as components in food systems that facilitate distribution of locally grown food in urban areas, using existing infrastructure with modified components. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and neither will a system of vertical farms. Public urban markets, which served as strategic food distribution centers in many US cities until WWII (often doubling as civic or transportation hubs and urban gathering places) were increasingly abandoned as refrigeration technologies, highway infrastructure and distributed urban development paved the way for supermarkets to usurp the ‘traditional’ role of public markets in everyday life. San Francisco, Seattle, Boston, and several other US cities have recently established or reclaimed historic buildings as public markets, although these projects have been criticized for being “contrived” as “Festival Markets”, which focus on the spectacle of commercial activity rather than functioning to support local food systems and their requisite economies. These so-called “Festival Markets” do contribute to the specter of a local food economy, but you won’t often find local residents shopping there. As is the problem with many farmers markets in urban areas, “Festival Markets” cater to an exclusive public (often tourists or the good old Habermasian bourgeois concept of public), have limited operating hours, and don’t carry convenience items. They are specialty, not everyday.

The SF Ferry Building Market. Photo by Flickr user: Life in a Yurt

And yes, it is also a scale issue. Is it even possible to scale up the informality, flexibility and activity of a farmers market to make it profitable and viable everyday? Good question…we’ll see how they do it elsewhere. Am I being nostalgic? Not the way I see it.

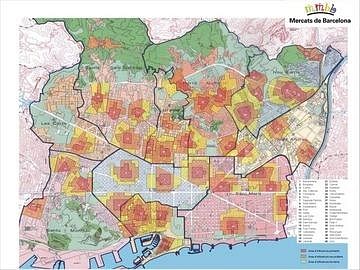

Considering the contemporary interest among designers in productive urban agricultural systems, there is a contradiction in the perception of markets as an outmoded historical typology. In cities with active public markets, these structures have the potential to perform as social, economic and cultural catalysts, operating as nodes in systems that support direct exchange between independent producers and urban consumers. Public markets in many cities around the world, participate in everyday local food distribution at a scale that farmers markets and “Festival Markets” in the United States currently do not, while contributing to public benefits that supermarkets entirely neglect. The city of Barcelona, for example, which supports an ongoing modernization project to remodel its 39 municipal markets, relies on public markets for a high percentage of its food distribution.

Barcelona Markets Map, published by the Barcelona Municipal Institute of Markets

A joint report published in 1995 by the Urban Land Institute and Project for Public Spaces, titled Public Markets and Community Revitalization, outlines a few of these characteristics:

1. Public Goals – “For example, attracting shoppers to a downtown commercial district, providing affordable retail opportunities for small businesses, preserving farming or farmland in the region, activating the use of public space. Markets have goals and effects that may benefit the public good, for education, commerce and ecology.” We may of course, argue about the meaning of a “public good”, for which publics, but at least we should be able to accept that public goals are beneficial beyond profit maximization for individuals or corporations.

2. Creates Public Space – “A public market need not be located on publicly owned land, as long as the privately owned land is easily accessible, the market may be perceived as public space.” Again, the concept of public space is highly contested, and dependent on how a space is activated by multiple publics uses and imaginations.(6)

3. “Public markets are made up of locally owned, independently operated businesses.” This is not your local food court.(7)

Public markets may be just one component of an active local food system, operating at a scale between wholesale markets (that sell exclusively in bulk) and farmers markets (that are almost always boutique).(8) The question of how a type of market, or network of markets could support a local food system is central to my project. It seems logical to me that a lack of existing retail options in the US may be the most limiting factor for more significant local food economies, especially in lower income neighborhoods. Alethea Marie-Harper, president of the Oakland Food Policy Council, and also a recent graduate of the UC Berkeley Landscape Architecture program, argued in her 2007 graduate thesis, “If networks of local distributors and processors could be established, farmers could be connected to local markets much more easily. This shorter supply chain would give both growers and consumers more control over the process, and result in higher profits for growers, and healthy affordable food for consumers. Rebuilding local food networks is a crucial part of working for food justice."(9) A local food system, generated by networks of public markets, could have significant large-scale regional benefits, including social, environmental, and economic repairs to both human and ecological systems that have been damaged by industrial practices, corporate greed, and compromised federal regulatory agencies. This is not a proposal for a return to a historic model of agrarian urbanism. Cities are getting more, not less dense, and we all know that climate change and mass urbanization are two immense challenges of our generation. An alternate system of markets could support an alternate system of agriculture (that is already happening, just not yet on an optimal scale). These are systems that have the potential to be safer, more efficient, more flexible, and more public than what we have now in the United States. We should look back just enough to see further ahead.

A Few Paradoxes

While the production and distribution of food (like other infrastructure) occurs largely outside public consciousness, growing consumer demand for local food has influenced the increasing scrutiny of global industrial agriculture and the space of retail markets. This growing demand in the Bay Area is evident given the increase in farmers markets, CSAs, institutional farm to table programs, and cultural documentation following the local food movement. However, despite having more than 100 farmers markets in the 9 county Bay Area, this mode of distribution remains less than 1% of total retail food sales. According to a 2008 report by American Farmland Trust (AFT), “Farmland conversion is [still] accelerating, particularly in the agricultural heartland of the San Joaquin Valley …where 76% of all land developed since 1990 was high quality productive farmland.” (10) At the same time farmers markets were taking off in popularity, both nationally, but especially in the Bay Area, an urban area within close proximity of much of our nations prime farmland! So, what is the limitation of the existing systems? The AFT report argues, “A big challenge to increasing consumption of healthy, locally-produced food is increasing consumer demand, including that of low-income consumers who do not have easy access to affordable food.”(11) However, other local experts, like Serena Unger, co-author (with Heather Wooten) of Oakland Food System Assessment: Toward a Sustainable Food Plan, have argued that the demand for local food is not currently being met by existing direct-marketing distribution systems.(12) Obviously there is no clear answer, but we can start asking a few more pointed questions:

How can cities increase food production and profitability for growers closer to urban areas (especially with dense populations)?

What are the potential alternatives to the current food retail system in the United States, and especially the Bay Area, and how can these alternatives promote comprehensive social, environmental, economic and educational benefits that are currently neglected by profit-driven supermarkets?

What are the urban and architectural opportunities for such an alternative system, and what form might these take at the scale of a retail market?

Where do precedents of an alternative typology exist, and how could lessons learned from them complement a thesis proposal for a local food system and public market prototype in the Bay Area?

How could the physical structure of market places affect the link between production and consumption, and how could this interface be strategically designed to support a more resilient local food system?

The full complexity of issues related to global food systems are beyond the scope of my project, but through an investigation of public urban markets as an urban typology, I will demonstrate the contemporary relevance and systemic potential of a typically nostalgic (and commercially appropriated) building type.

Itinerary

My somewhat tentative travel itinerary is as follows:

(January 18 – February 29) Mexico City

(March - May) Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paulo, Montevideo, Buenos Aires, Mendoza, Santiago

(May – July) Rabat, Fez, Granada, Valencia, Barcelona, Beirut

(July-September) Avignon, Paris, London, Copenhagen, Latvia, Budapest, Venice, Rome

(September – October) New York, Philly, DC, Cleveland, Seattle, LA

(October - December) Tokyo, Hong Kong, Bangkok, Istanbul, Koudougou (Burkina Faso)

I look forward to your comments, and hope that this blog can support the expansive discussion about food systems relative to urban planning, architecture and infrastructure. I also welcome any suggestions of places that you think are worthwhile visiting for my research. I am somewhat flexible within my given schedule. Finally, if you reside in any of my proposed destinations, let’s meet for a lively conversation, or just a drink, or whatever. Thanks for reading, until next time, logging off…

Citations

(1) Pierre Belanger. Interview with Jennifer Leonard. http://www.recodemagazine.com/interviews/pierre-belanger

(2) Meredith Tenhoor. “The Architect’s Farm” in Above the Pavement – The Farm! Architecture and Agriculture at P.F.1. Amale Andraos and Dan Woods, eds. Princeton Architectural Press, 2010. p.188

(3) Dickson Despommier, The Vertical Farm. St. Martin’s Press, 2010. p.129

(4) http://www.economist.com/node/17647627

(5) Steve Martinez, et al. "Local Food Systems: Concepts, Impacts, and Issues", ERR 97, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, May 2010. p.48

(6) For further reading on shifting definitions and meanings of public space, see two articles by Margaret Crawford. “Blurring the Boundaries: Public Space and Private Life”, in Everyday Urbanism, by John Chase, Margaret Crawford and John Kaliski, Monacelli Press, 2008.; and, “On Public Spaces, Quasi-Public Spaces and Public Quasi-Spaces” with Marco Cenzatti, in Modulus 24, 1998.

(7) Theodore Spitzer and Hilary Baum, Public Markets and Community Revitalization, Urban Land Institute and Project for Public Spaces, 1995

(8) For more about wholesale markets and farmers markets, see science writer Thomas Hayden’s blog post, at http://www.lastwordonnothing.com/2011/10/04/local-food-appetite-for-infrastructure/

(9) Alethea Marie-Harper. “Repairing the Local Food System: Long-Range Planning for People’s Grocery”. Master of Landscape Architecture Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 2007. p.2

(10) Sibella Kraus, Harper, Alethea Marie-Harper and Edward Thompson, “Think Globally-Eat Locally: San Francisco Foodshed Assessment”, American Farmland Trust, 2008. p.13

(11) ibid, p.17

(12) Serena Unger. Lecture at SPUR, SF title “The Future of Bay Area Agriculture”, Sept. 14, 2011

I am a graduate M.Arch/MLA student at UC Berkeley, and grateful recipient of the 2011-2012 John K. Branner Fellowship, an annual traveling fellowship awarded by the UC Berkeley Department of Architecture. I will spend the 2012 calendar year visiting public food markets in major cities on 5 continents to research the relationship between markets and the infrastructure of food systems, focusing on the cultural and urban design implications of local economies. This blog will follow my journey...

1 Comment

I take this is more a spatial exercise of distribution than production. It's nice to see some US destinations - I hope most include the "affordable" portion as all this local food craze seems to be focused on those that can afford to pay a premium on food, and food items that is outside the standard cultural foods of those that can't afford to eat. Economics aside (many european countries have spent massive amounts on subsidizing local farmers and local markets often had foods from far away - in the German town I lived in, most of the fruits and vegetables were grown in Greece or Spain in the cool months; they needed those sources to be economically viable year round).

On a related note what range of food is this for (meats, grains? is that grown in the San Joaquin?), fruits and vegetables see to be able to be grown in urban areas with relatively profitable margins. Grains require square footage.

SF may be densifying, but many others are not, are you assuming that if it's possible at SF real estate prices, that it is replicable elsewhere? Is trying to make such a grand statement appropriate?

Are markets the necessary proto-type? I can't help notice that the local food group in New Haven has a strong community w/o associated markets; they share a community garden, share their own produce, grow grain communally have salon-style gatherings. The farmer's markets work well for the middle and upper-middle classes and students, hardly ever does one see the lower income brackets included (ie not very democratic). The AfH Chicago's food bus seems like a better alternative (and in line with the parklets of SF) - they're mobile and do not rely on stationary real estate.

As for designers interest in the topic - it comes in a little late but it is trendy (hate to be cynical but the criticism leveled at designers who do not consider economics or social science in proposing designs is valid, and advocating the interest of the privileged as a game changer for social equity when done poorly is horrible (Pruitt-Igoe). The question I would pose is what are typologies that are familiar and currently existing that can be adapted more responsibly for a larger systematic change (let's face it, the local bodegas in many cities do exactly what small european food markets do).

To phrase it another way what is a more post-modern multi-narrative solution that is adaptive (tactical interventions), it may be semantics, but the way the statement is written it seems more that you are looking for a uniform, top-down, single solution answer. IF you are implying this is a more democratic food distribution system it necessitates an alternate systematic approach (and different images, there's plenty out there).

Good luck!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.