architect: Wang Shu, Amateur Architecture Studio, 2009

photos by the author.

A few months ago, I took a weekend trip from Shanghai down to Ningbo. The recently completed Hangzhou Bay Bridge (briefly the longest on earth, before it was surpassed by another, elsewhere in China) cuts the travel time down to 2.5 hours (even faster than the new high-speed rail, which connects Shanghai and Ningbo via Hangzhou). I'm constantly amazed by the infrastructure here, which turns the entire Yangtse delta into a huge, networked agglomeration, each city (Ningbo, Hangzhou, Shanghai, Suzhou, and Nanjing) merely a node of this increasingly interconnected organism. It gives me hope, too, than while development speeds ahead in Shanghai, the old-China charms of Suzhou and the natural beauty of Hangzhou won't be lost in a sea of towers.

Ningbo has only a few sights to offer tourists, but it's a painless trip, and as a former Treaty Port (with it's own miniature Bund) it offers some interest to architects and urbanists... so off I went. The “LaoWaiTan” area – Ningbo's “Bund” is a charming, subtly-restored collection of colonial buildings – former banks and customs houses – converted into restaurants, bars, clubs, and housing. The approach is less strictly preservationist than that of the Bund in Shanghai, where the facades remain pre-war postcard-perfect. Throughout LaoWaiTan are scattered contemporary apartment blocks, rising up behind the restored treaty-port facades. The attitude toward preservation in Ningbo - a city a bit out of the spotlight – seems to be more subtle, and more flexible, than the attitude in Shanghai, where conclusions are binary (old building stock is either historically significant - or not – thus is either painstakingly restored - or demolished).

This attitude is nowhere more clear than at the Ningbo Historic Museum, completed in 2009 by architect Wang Shu (of Amateur Architecture Studio). Photos of the building circulated widely when it was completed, and Wang Shu has gotten a lot of recent press for good reason – this is hands-down the best work of contemporary architecture I've yet seen in China.

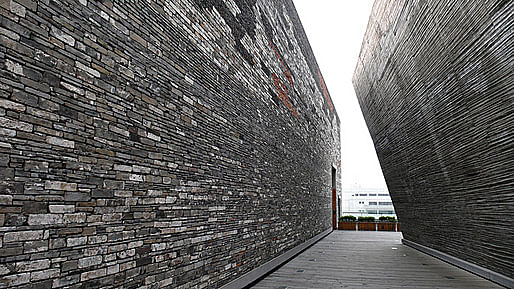

A quick stumble through the blog-o-sphere will explain the facade, clad with bricks and tiles collected from demolished buildings in the area, but the museum's attitude toward history is much more nuanced than a simple recycling of building materials.

The facade is beautiful, no doubt. The approach used in the construction process (the workers were apparently free to select and place the bricks at random) is in line with contemporary western attitudes towards “organic” patterning and randomization, and the “sustainable” benefits of material reuse are basically unquestionable, but the real power of the building derives from its form.

The museum is sited in a landscape typical of contemporary China: tree-lined boulevards divide the district into distinctly zoned blocks: residential, retail, government. The museum faces a municipal office building across a wide swath of asphalt, and is backed up against a pleasant (but perhaps oversized) park. The block is ostensibly the town center of a new central business district, but the surrounding blocks remain somewhat underdeveloped, awaiting tenants and activity. The site is a dozen kilometers from the historic center, and the building is seen, first, as a sculptural object in the landscape.

The striking form benefits from this reading: the angular cuts are utterly contemporary, and could easily be the result of boolean operations in any popular modeling program. As a material object, it's impressive, but there is more here than simple formal manipulation. One can imagine a series of diagrams demonstrating how the form is derived from an ideal rectangular volume, cut through with voids where atria are required for interior daylighting, or slashed horizontally where views across the city are desired; the form responding by reeling back and outward from the cuts, vertical facades tilting outward in natural, physical response to these lacerations.

One can imagine the cuts occurring at specific points, along certain vectors driven by the optimum size and depth of a gallery space, auditorium, or cafe.... but these cuts serve a greater theoretical purpose: by slicing away at the ideal extruded form of the building, the architect breaks down its monumental scale, and recreates – on the accessible roof-scape – the human-scale proportions of a traditional Chinese village.

The voids slashing through the building intersect at angles that instantly recall the pitched roofs of local vernacular architecture; the cuts are sized to recreate the scale of pedestrian lanes; the interlocking solids and voids of the roof level create an urban plan (at the scale of pre-modern urbanism), thus referencing and recreating the spatial experience of classical China.

(A cynic could go a step further, and say that the reconstruction of classical urbanism on the roof-scape amounts to its placing on a plinth - preserved but abandoned – as the culminating exhibit of the Historic Museum's permanent exhibition.... but – today at least – I prefer to be optimistic.)

And this is where the building's power really lies: in its ambitious (and ambiguous) synthesis of the contemporary and the traditional. Technology-driven form-making and traditional construction techniques are used in tandem. The building is at simultaneously a sculptural object and a field-condition: architecture and urbanism. The attitude toward history here suggests a way forward for Chinese architecture that doesn't rely (solely) on flashy renderings and iconic forms, but can retain those essential qualities of the historical fabric that make China's ancient cities so appealing, those qualities most endangered and vanishing rapidly in the rush of modernization.

---

More (and larger!) photos, as always, on the author's Flickr page.

This post originally appeared on the author's blog, Tenuous Resilience.

reflections on architecture and urbanism in China.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.