"Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men's blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work."

— Daniel Hudson Burnham (1846-1912)

“yes i was wondering how i go about not lossing my house it has been in my wifes famlily for over a hundred years my wife was layed off the morgage company wouldnt talk to us because she was layed off and now we are so far behind we cant get cought up so now we are loosing our home is there help out there for me”

— unedited comment from MoMA workshop blog (2011)

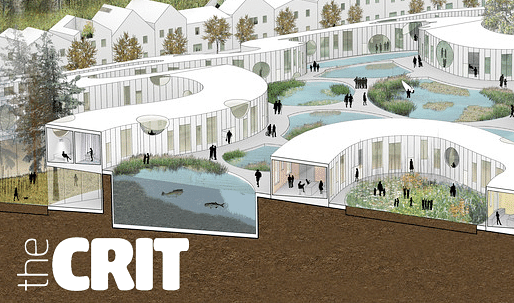

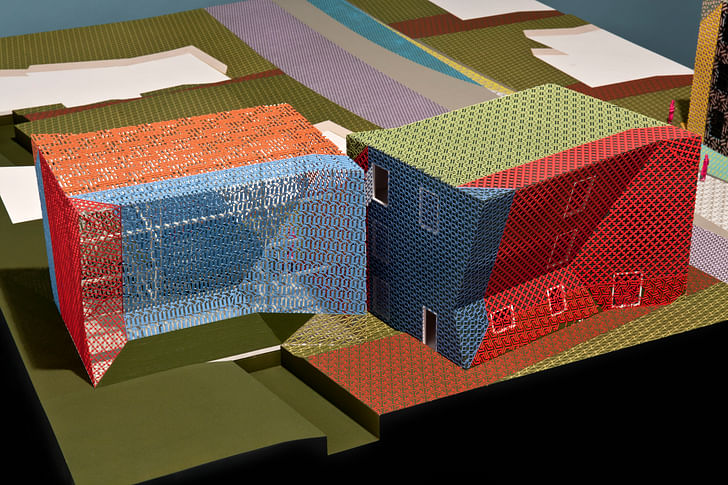

In Foreclosed: Rehousing the American Dream, part of MoMA’s Issues in Contemporary Architecture series, five architects-in-residence and their interdisciplinary teams [1] were challenged to “engage in a rethinking of housing and related infrastructures that could catalyze urban transformation.” The investigation also sought to “begin a conversation,” on the “recent” (though painfully on-going) foreclosure crisis by examining suburban housing paradigms through five sample megaregions.

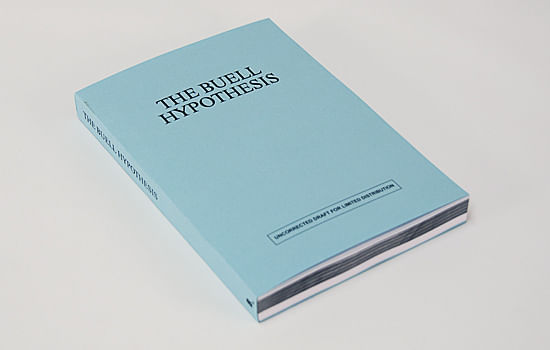

The workshop-exhibition was jointly organized by Barry Bergdoll, MoMA’s Chief Curator of Architecture and Design and Reinhold Martin, Director of Columbia University’s Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture.

The Buell Center also authored the document that would serve as the unofficial brief for the investigations. The Buell Hypothesis: Rehousing the American Dream (a forthcoming book) is premised on the theory that the culture of the American suburb is driven by a persistent historical fantasy [2]. “What is, or was, this dream?" [3] it asks (p.18).

The Hypothesis (worth reading in full) seems to have taken on the status of operating system, the underlying code for how to perceive and frame the “problem” of the suburbs. It’s influence can be read in all the projects. But so can the influence of architecture as a discipline—being somewhat institutionally slanted toward envisioning the American suburb as an intellectual and spatial problem.

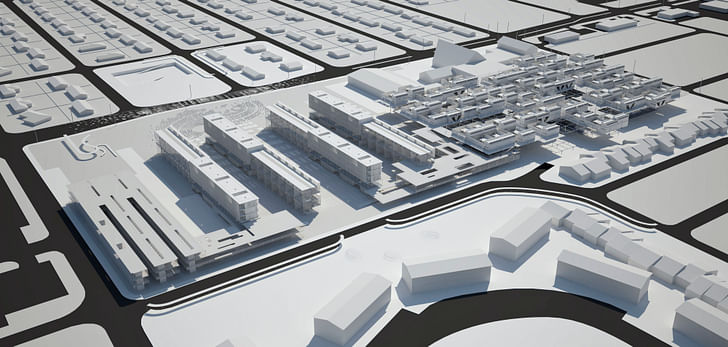

To be clear, the mission was not to solve the current foreclosure crisis [4]. Instead, the teams were charged with catalyzing, rethinking, and conversing about it. And they were asked to do this on a massive conceptual scale. Given the enormity of the task, it’s understandable if the architectural results are big. How could they not be?

This essay is not intended to be an exhaustive critique of the proposals [5]. It is, rather, a way to begin a conversation about what the proposals could mean in a larger sense. When I first began following the progress of Foreclosed it prompted some basic questions: Does such bigness run the risk of replicating the big problems in other guises? Does the knowledge produced by those other interdisciplinary disciplines get obscured by the big architecture? How does architecture catalyze and coalesce information generated from other fields and then bring this to bear on spatial considerations? Do the proposals either enhance or meaningfully communicate the content produced by, say, economics, geography, history?

The paradox—and the conundrum for the architects—is that when the Buell Hypothesis is deployed as a theoretical basis, it becomes almost impossible to escape the trap of replicating the fantasy they are critiquing. Additionally, no matter how compelling the substitute fantasies may be, they run the risk of falling flat in the midst of the larger cultural moment going on outside MoMA’s galleries [6]. So not only do these architects have to contend with addressing real problems, they must also responsibly navigate the terrain between the real and dream states set forth by the Hypothesis [7].

Foreclosure might then be viewed as a framework for re-envisioning the American Dream and architecture’s role in that dream.

But really big plans give rise to contradictions. Their bigness and drama and complexity are also problematic, challenging, and even disturbing because they bring to the fore the drastic steps required to address current problems. You have no choice but to send Captain Willard upriver in a boat, to sanity’s final station.

They demonstrate that we are still trying to comprehend and map what these suburban configurations are and how they can be constructively acted upon. Often viewed as a long-term degenerative disease that has afflicted America in its recent history, suburbs can have deep roots. While a city or town or neighborhood can be a teenager geographically, they are the result of processes that took hundreds of years to evolve, going back to the nation’s earliest land experiments. Thus, they comprise part of the deep structure of American spatial culture and communicate via built form the psychologies of real estate and the economy.

Architecture is here seemingly offering shock therapy to shake us out of a supposed complacent acceptance of suburbs. Repeated shocks, when strategically applied to a stuttering confused middle and working class, can perhaps offer a cure. But is this the real audience? The general public? Or, are the proposals primarily for professional consumption, though in the guise social altruism? One might guess that had they been geared for the general public they might have maintained more of the present tense and exhibited less science fiction.

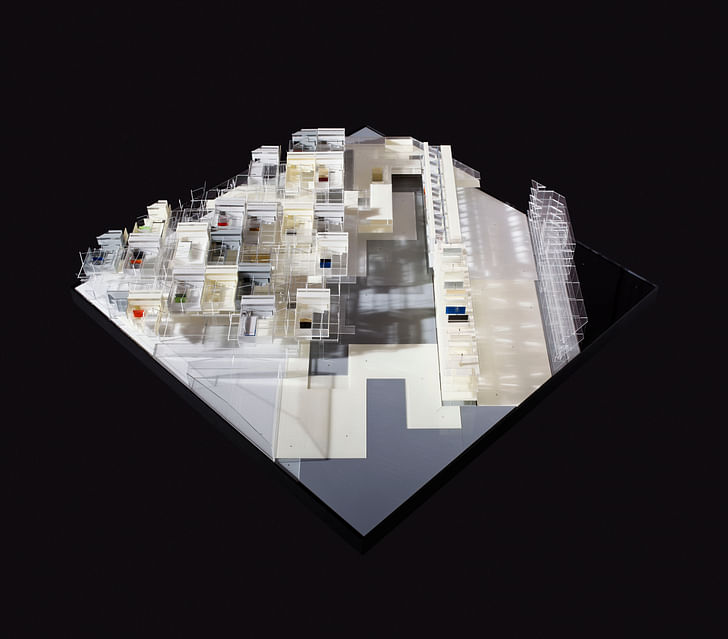

These totalizing impulses, common to architectural discourse, strive to encompass all possible contingencies by re-defining suburbia along the lines of dense ideal urbanities. Questions of audience aside, such gestures could be taken to be constructive. And, quite possibly, we need such gestures, the insinuation of the new (no matter how fantastic) in order to see our way to potentials hidden in the midst of what we are currently stuck with. Yet in this process, the inherent heterogeneity of suburbs become flattened. They become objects upon which total transformations are imposed.

The imposition of professional, taxonomical knowledge obscures the complex social, spatial, economic, and cultural aspects of these territories. The realities of the suburbs—their spatial and cultural resiliencies, their persistence (not to mention formal mechanisms of governance)—suggest that big plans cannot rule the day. Foreclosed can thus be contextualized in the history of urban renewal, slum clearance, public housing, and other such large-scale, top-down housing policies that have failed. History seems to demonstrate that micro-transformations, house by house, lot by lot, bottom-up renewal, will most likely define the limits of suburban change [8].

But projects that explicitly demonstrate a micro-incremental future still contained in the current suburban framework are not dramatic enough. Thus architecture tends to leap forward, unfettered by the constraints of process and history—even though ostensibly grounded in the interdisciplinary data.

As one example, MOS Architects (undoubtedly under the influence of The Buell Hypothesis) dismisses the street, the block, and the playground as spatial mythologies. They probably didn't mean it the way it sounds. However, as indicated earlier, their solution reaffirms the same trope by superimposing Constant’s New Babylon-redux upon the old neighborhood—a new fantasy in place of the old.

While the issues posed by Foreclosed can be theorized at the scale of the neighborhood, the city, the megaregion, it is very possible that they cannot be solved at this scale. The proposals have to reclaim the specifics of heterogeneous and historical contexts—context that could only have arisen over long periods of time and cannot be replicated with a swiftly and dramatically articulated master plan.

In architecture we have become inured to the special effects of formal bigness and dramatic constructs. We have been trained to think in bold terms. Architectural history, after all, privileges the heroic, not the minor [9]. Thus in Foreclosed, Architecture strives to surpass the ordinary. Thus many of these projects foregrounded the assumption that suburbs are just too boring, too pedestrian.

Do these towns really need the drama of design spectacle? What is the ontological value of the ordinary in contemporary architecture? Does architecture accept the consequences of alienating itself from everyday things? Maybe the interdisciplinary teams should have included a representative from the respective communities. Oh, but they don’t know what they want or they want the wrong things. So, this would have caused trouble.

Of course, there are expectations for drama that come with anything associated with MoMA. These are proposals designed to stir audiences. What comes across in some of the videos, however, is a mixture of boredom and malaise. The bored might be the archi-geeks who have already seen such things in countless presentations. Those appearing baffled are probably members of the lay public wondering why architects are making such radical, disconnected proposals and why they have never seen anything like this out in the real world. To them, this is further evidence of the irrelevance of what architects have to offer in terms of solving real problems. Not good for marketing, that.

This is a shame because there are some valuable ideas. Ironically, most of those are contained in the boring data taken from economists and social scientists. Were the architects trying too diligently to spatialize the data? Though, coming from architecture, I can appreciate the designs, they also make me somewhat suspicious. The projects all seem to dissolve in their quest for mass solutions, broad connectivity, and constructed diversity. They might have succeeded more by discretely focusing on a few foreclosed properties rather than globalizing entire neighborhoods and megaregions. As unsettling as the damage the financial crisis has wrought on the fabric of dwelling in America, the distance these proposals travel away from what caused these foreclosures is equally unsettling.

Thus for example, would people really favor cooperative over individual ownership, or is that being proposed because one proposal assumes the American Dream is already gone? Is the detached dwelling on a postage stamp lot to be done away with for sustainability reasons or is it simply a case of detached homes being conceived of and sited in the wrong ways? Should we all be farming, riding bikes, and taking light rail? This doesn’t take into account patterns of employment and assumes people can afford to live close to where they work. One of the dominant forces that drove the suburbs was affordability, not just a flight from urban congestion, pollution, and crime. People keep moving further and further out because of the lure of ownership that is affordable, not because they are necessarily escaping something. To make any of these proposals tenable the economic system that has been eroded for the last thirty years has to be re-built. That dirty word, socialism, could get them off the ground!

The path to rehousing the American Dream is going to be a long and winding road of economic and political adjustment. The spatial ambitions shown in the architectural proposals do not represent the suburbs as we know them, but this is the point. They do, however, begin to indicate how the suburbs and property could be re-imagined. As for rehousing. That has to be deferred, yet again. In the meantime, construction indicators show lots of new apartment developments going up.

Presentation Videos:

The Foreclosed exhibition runs from February 15 to July 30, 2012.

Notes:

1. From MoMA:

Amale Andraaos and Dan Wood of WORKac and their team are looking at Salem-Keizer, Oregon, within the Pacific Northwest area; Michael Bell of Visible Weather and his team are studying Temple Terrace, Florida, within the Southeast area; Jeanne Gang of Studio Gang and her team are looking at Cicero, Illinois, within the Midwest area; Hilary Sample and Michael Meredith of MOS and their team are studying The Oranges, New Jersey, within the Northeast area; and Andrew Zago of Zago Architecture and his team are looking at Rialto, California, within the Southern California area.

Team members were comprised of professionals from such diverse fields as ecology, various branches of the social sciences, engineering, housing policy, and urban planning.

[2] Most of the reference citations in the Hypothesis are government reports and websites as well as many journalistic sources on the on-going mortgage and banking crisis. Additional areas of inquiry that would have enhanced the historical perspective include reconstruction after the Civil War and how this played a role in shaping the suburban "dream"—much of which can be traced to post-Civil War reconstruction and efforts to redefine a fractured nation. Eric Foner and Jackson Lears are excellent sources for this. The literature of manifest destiny would also seem important. Anders Stephanson is one example. Also, the history of the railroad and the highway. Keller Esterling's Organziation Space, for example. Oliver J. Dinius and Angela Vergara's book, Company Towns in the Americas: Landscape, Power, and Working-Class Communities. Let us also not forget Henri Lefebvre's The Production of Space. The intersections of geography, cartography, and law in defining the space of property are also worth investigating. A good source for this is Andro Linklater’s important and well-written book, Measuring America.

[3] Though history may be constructed as a "dream" of sorts, the embodiment of history has social and spatial implications. Dolores Hayden's The Power of Place is just one example of the social and psychological importance of location and the internalization of place. On some levels we need to "dream" in order to locate ourselves in physical space. Right or wrong, suburban or urban dreaming has become a persistent social and cultural practice that impacts millions of Americans. How can the dreaming be inflected?

[4] The brief, then, did its job. It influenced the proposals by privileging a particular vision of suburban history over other possible narratives. But by focusing on a single narrative, different suburban imaginaries are rendered overly simplistic. But as in life, there should be more than one narrative here to generate different approaches and proposals, aligning them more closely with the complexities of the present material reality Warning: long sentence ahead! The intellectual and theoretical project of reducing a complex physical and social environment to the status of a mere historically-contingent fantasy that people subscribe to (and are duped by) denies the importance of suburban subjectivity and lived experience transmitted within families and other social groups.

[5] Let’s just get that out of the way, shall we. The last time I was in New York the Twin Towers were still standing. I watched them go down from a tiny hotel room in Wanchai, Hong Kong. I floated like a ghost down to breakfast and then went back to my room to watch the Towers fall over and over again for hours. Then I turned the TV off, the way Captain Willard switches the radio off at the end of Apocalypse Now. Point being, that I haven’t viewed the work firsthand and I’m not pretending to have done so. Foreclosed inspired thoughts about what the foreclosure crisis means and prompted questions about how the crisis and it’s spatial practices are conceived. If you are in New York, would you mind popping on over to MoMA and writing up reviews of the individual proposals? Somebody is bound to be doing this. Or, nobody will care and nothing further will be written about it. It’s best just to go and see it for yourselves and come up with your own conclusions.

[6] Communities have been fractured, families displaced. The social fabric of neighborhoods torn apart. Tax bases have been disrupted. When neighborhoods experience such wounds, their recoveries become extremely difficult to conceive. So in that sense, maybe it does almost require tearing everything down and starting all over again. Is there room for empathy?

[7] It would have been interesting to see what the results would have been with a more critical reading of the Hypothesis. An epistemological lens that questioned it’s very formation and underlying assumptions could have yielded different ways of seeing the suburbs emerge. There is the sense that, despite the differences in context, all the architectural teams subscribed to the “fantasy” narrative, or views of the suburbs that are particularly negative. Liking the suburbs in architecture is like admitting you like soft rock.

[8] Or is it the historicization of failed top-down renewal policies that largely determines the expectation for large plans to fail? Are there examples of housing policies enacted across large territories that have succeeded and continue to exhibit success? This history of the modernist approach to master planning perhaps obscures nuances that have been developed in contemporary times. In other words, are we looking at these contemporary proposals through a lens fogged by a history of failure? Has architecture found a way out of these failures? Is any large plan doomed? Just plant lots of trees?

[9] To be understood in the Deleuzian sense of multiple combinations and endless re-combinations that produce new cultural forms.

Guy Horton is a Los Angeles writer and author of the critical blog, The Indicator on ArchDaily.com, which covers issues ranging from the culture, politics, and business of architecture to theory and aesthetics. He is a frequent contributor to The Architect's Newspaper, The Atlantic Cities ...

2 Comments

I read the first version of this essay that was "accidentally" released and seems there is a much more critical (although not necessarily negative) vibe to this newly released version. I like it more...

As for the proposals outlined above, granted I haven't seen the exhibition or read the book but from what you describe and what else i have read it seems that there is a lack of strategies or tactics proposed to address housing crisis. Which would seem more appropriate than the formal projects that are presented. Maybe it does have to do with the brief, but it seems like there is a focus too much on the suppositional and not enough on the mundane nature of actually tackling all the empty lots. "Rethinking" suburbia isn't same as developing tactics for re-housing or re-purposing foreclosed housing.

What would something like #whownspace or other forms of spatial activism for foreclosed properties look like i wonder....

Additionally, in light of all the ongoing talk in our forums re: the future of the profession it seems illuminating that you wrote " Ironically, most of those are contained in the boring data taken from economists and social scientists. Were the architects trying too diligently to spatialize the data?"

What does it say that a exhibition whose goal is to articulate how architecture can address key contemporary issues, clarifies that non-architects/design are perhaps better equipped to illuminate these same issues?

That's because you saw the first draft that was accidentally put up instead of the final! Glad you like it. Would like to hear what people think about the exhibition once it opens in NYC. I have a suspicion architects have very little to do with the solution side of the crisis are are merely along for the ride. If architects had more power in Washington it might be a different story. But, then, rethinking things is probably not enough.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.