Genevieve Goffman does not create art about artificial intelligence; at least, not yet. The New York-based artist has instead grounded her acclaimed work in fantasy and narrative world-building, often through the medium of evocative and ornate 3D printed sculptures derived from digital modeling.

While not engaging directly with AI, Goffman’s work finds common ground with contemporary AI discourse through their mutual addressing of the human condition. Reflections on technological progress, failed human ambitions, and digital afterlives weave their way through Goffman’s work to create an indirect bind with AI-inspired reflections on humanity’s ability to define its present and chart its future. In this light, it is no surprise that Goffman’s latest piece The View, sits alongside a selection of architects and designers at the forefront of architecture’s AI discourse within the exhibition /imagine: A Journey into The New Virtual at the MAK in Vienna.

In June 2023, Archinect’s Niall Patrick Walsh spoke with Goffman on how her career has unfolded, including its grounding in both fantasy and 3D printing. We also reflect on the relationship between technology and culture in her work, including The View, as well as her thoughts on the relationship between designers and critics. The discussion, edited slightly for clarity, is published below.

This article is part of the Archinect In-Depth: Artificial Intelligence series.

Niall Patrick Walsh: Could we begin with an introduction to you and the art you engage with?

Genevieve Goffman: I am an artist based in New York who works primarily with sculpture and object making. I’m interested in history, the passage of time, and the way we reflect on progress be it technological or social. I’m also interested in architecture as a marker of time, or a holding place for ideologies and how they change over time. I work a lot with world-building, fantasy, storytelling, and tropes I pull from the internet language around fantasy, anime, and archetypal stories that exist both online, on television screens, and in fantasy literature.

I work heavily with 2D and 3D printmaking. I’ll often create 2D collages and 3D designs that become buildings or small worlds. Within these worlds are characters that play out narratives often emerging from real-world historical events. I enjoy stepping back into these histories, pulling from them, and perhaps mystifying them in certain areas or turning them on their heads.

How did these two components of fantasy and 3D printing emerge in your life to become so central to your work?

Narrative and fantasy have always been a huge part of my life; I’ve always been a fantasy nerd. At the beginning of my artistic career, I was working in an academic, neutral, black-and-white style that was very language and research-based. But for me to continue to be interested in my own practice, I knew I needed to rediscover the fantasy world that had always fascinated me as a child and teenager, everything from Greek mythology to the Lord of the Rings. I knew how to communicate in this language simply because I had been so exposed to it growing up, and realized that I could bring this to my work while also engaging in contemporary fantasy through anime or internet worlds. Fantasy, therefore, became a vessel for me to displace history in a different realm.

I often focus on our relationship to the passage of time, and the ideologies and neuroticism we create around progress in the future. — Genevieve Goffman

3D printing was also an interest that developed over time. My earlier work used text and image collages before 3D modeling entered my process. I was born with a muscular disability which meant I couldn’t hold a pencil or sculpt clay as easily. Because those artistic mediums weren’t available to me, I adopted computers. With 3D modeling, I felt I was able to create accurate representations of my ideas for the first time. It also intersected neatly with my background in collages. I was able to pull actual 3D scans of existing architecture or objects, or material from video games, and bring them together in one place. I was suddenly able to realize my own mental imagery perfectly, but also combine it with my wider interests. Fantasy and 3D printing went hand-in-hand.

3D printing and the digital also bring their own dimension to my work. I often focus on our relationship to the passage of time, and the ideologies and neuroticism we create around progress in the future. In the art world, there is a certain resistance or pushback against 3D printing and technology, though much less so now. These methods were an effective way of showing that my work existed in this other world of the digital as well as being a holding place for a conversation around progress, technological advances, and the dogmas, fears, and anxieties they evoke in people.

You mentioned that because of your muscular disability, computing and 3D printing offered you a more effective way of expressing your artistic thoughts. This is a reflection I hear from some architects, and the public at large when they use recently-released generative AI tools such as Midjourney. Because these tools operate off text prompts, users don’t need to have excellent drawing or even image-making abilities to produce provocative, meaningful work. The fact that your early work dwelled on poetry and text collage is interesting in this context. People today with that same basis in text have a whole new medium for translating their work visually.

Technology was critical for me in becoming an artist. There are always ways I could have found various workarounds even without the technology available to me. Being an artist is about problem-solving in some ways, and there are a million ways to make art. This is also not to devalue drawing and painting because there is an innate skill to those crafts. But what I do with computers is also skilled in a sense.

One of the hard pills that people have to swallow with AI now is where does artistic skill lie? If someone says “I am an artist, and the art I make is a straight language-to-image translation,” I would be the first person to say that is art. The question becomes: Is it good or not? Is it effective? That is a much more fundamental question to me than if the art is valid or skilled.

The idea of losing your job as an artist is very complex. I think there will always be fine artists for better or worse. — Genevieve Goffman

I haven’t found myself using new AI tools in my work yet, though I can see it as something I will approach soon. A fascinating part of these tools for me is their potential for collage. I could create images and, instead of using the entire image, could pull it apart in Photoshop and create something entirely new. There’s so much potential for me there. At the same time, I understand why technology can evoke fear and anxiety in people. If you have an artist with terrific craft skills, and hand-eye skills that allow them to paint, draw, sculpt, or make furniture to a high level, and then another person comes along and says “Oh, I can do this with a computer,” I can understand the anxiety of losing one’s place. The art world especially is a cultural scarcity, so I can understand the fear.

That said, the widespread fear of job loss by AI is less clear in the art world. The idea of losing your job as an artist is very complex. I think there will always be fine artists for better or worse. We are creative parasites living in society and we are not going anywhere. But more broadly, people are already losing their jobs to AI and that is very frightening for people to go through. Then on the other side, there is a tech optimism that I especially saw at the MAK exhibition in Vienna we talked about offline. There are artists and designers there who are very excited about the future of AI.

It is hard to imagine something like this having a solely liberating or positive impact, especially when it is being rolled out by tech companies that, for the most part, are not our friends. — Genevieve Goffman

This all comes back to a central theme in my work, which is progress. On one hand, you have this deep anxiety while on the other hand, you have utopian thinking, and both are equally valid. I don’t think AI will ever make me lose my own job, but I do know that it will make other people lose theirs. Maybe technology will open doors for these people in a different and liberating way, and my own career certainly wouldn’t exist without it, but we don’t live in the best of all possible worlds. We live in a very dark world. It is hard to imagine something like this having a solely liberating or positive impact, especially when it is being rolled out by tech companies that, for the most part, are not our friends.

As you alluded to earlier, your work is currently part of an exhibition at MAK in Vienna titled /imagine: A Journey into the New Virtual. You produced an art piece titled The View. Could you give an introduction to the piece, and how it came about?

With The View, I did something that I found myself doing a lot, which is taking the prompt for the exhibition and, rather unintentionally, exploring something that tangentially touches on the prompt but also goes in an unexpected, different direction. When the organizers asked me to create a piece on the theme of virtual worlds, they may not have been expecting me to embark on three months of research on the pivotal points in Viennese architectural history and build my work from that. But that's the journey I found myself on.

We are struggling to idealize or create a definition of our time, which by extension will define the future. — Genevieve Goffman

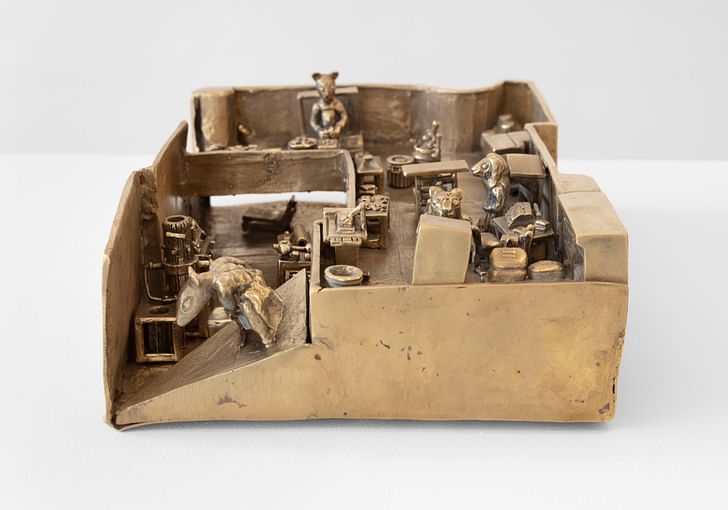

With The View, I created two opposing balconies separated on a six-foot-long pedestal. One balcony is roughly based on a romanticized version of the architectural work of Adolf Loos. On the other side is another balcony looking at Red Vienna-style buildings; public housing buildings that Loos set the city on a trajectory to build, but which are a sort of extension of the Modernism that he was trying to bring to Vienna.

An interesting part of art for me is the ability to tell stories. In The View, I created a series of characters. One is based on the character of the architect, Loos, who is gazing into the future and looking at a building that he had a hand in manifesting but wasn’t directly the architect of. It is a building that is coming to him from the future, appearing in front of him as his stamp on Modernism. This other building contains three female characters who are interacting with the space in their present moment. Despite the historical reflection, I was actually thinking about my relationship with the virtual. This was a period of time which was struggling to define what ‘modern’ meant, and as an extension, what the future would be. I feel that the same conversation is taking place now around virtual reality and AI. We are struggling to idealize or create a definition of our time, which by extension will define the future.

Architecture is a highly effective timepiece and timekeeper for detonating the period we are in, but also for housing the ideology that we are trying to project on the present and future at any given moment. — Genevieve Goffman

Loos was an important but heavy character to address in the piece. He was a highly influential figure in design and ornamentation, and yet also had this relationship with voyeurism and pedophilia. He wrote a book about fashion and how the modern man should dress. He had particular ideas about what a public modern figure was and was highly assertive in defining it. In my piece, the Loos character was the driving narrative behind the building he occupies. Here is this architect sitting in this beautiful house he made, gazing out the window at these women living in a future house that is beyond his intervention. He is addressing how his life’s work of defining Modernism is eventually out of his control, which again is how I feel about our relationship to the virtual, technology, and AI.

Then there are the three women, each with their own character and message. One of them is pragmatically relating herself to the physical space around her, but also looking out to the future. Another is gazing outwards into the future with excitement. Another is dreamily looking backward at the architect. Together, they represent how we relate metaphorically to this idea of time, but also technology and technological change. This is why I always often return to these direct architectural references. Architecture is a highly effective timepiece and timekeeper for detonating the period we are in, but also for housing the ideology that we are trying to project on the present and future at any given moment.

Even if you felt The View’s subject was a departure from the exhibition prompt, it’s fascinating how the piece, and particularly your own reflection on it, offers rich food for thought on the AI discourse today. Perhaps that is something we can explore more in a moment, but I wanted to first ask if you could give an insight into how the process of creating The View aligns with your other works. Was it a similar process to previous projects, or did you find yourself exploring new ground?

It was both, actually. In the past, my work has dwelled on the Baroque, Gothic, and cathedral or palace-like fantasies. For whatever reason, I decided for the first time that I would address the realm of architectural Modernism. This was a challenge at first but, on reflection, was rather fun. I found myself building Red Vienna projects from scratch in Blender using pictures of social housing projects or the exteriors of Loos houses. Then, like in previous projects, the production relied on 3D printing using MJF (multi-jet fusion) nylon. As MAK had access to 3D printers, the entire work was produced there. Nylon is an excellent material to work with. It produces a heavy, stone-like texture which often compliments my style of design.

The pedestal supporting the work is decorated to look like a palace with beautiful ornate windows which, again, were designed by studying photographs of Viennese buildings and creating my own alternate reality interpretation in Blender. As can be seen in my other works, I have a clear preference and intrigue for the Baroque and ornamental, but working more closely with European Modernism gave me an appreciation for that style and an insight into how revolutionary it was when it first appeared.

When I look at The View, and your work more broadly, there are clear thematic overlaps with modern AI discourse, which is fascinating considering you don’t directly engage with it as a tool or subject. I was reading a review of your 2022 project Before It All Went Wrong, and there were several phrases and terms which go to the heart of our conversations on AI: not just the narrow discussion on generative AI tools, but broader reflections on what AI says about human intelligence and its place in a hierarchy of universal intelligence.

In the review, I read about “progressive visions of the future,” “fantasy of a workfree society,” and “the horrible beauty of human imagination and failed ambitions.” The closing lines of the review are also intriguing: “Goffman’s work often delivers a sense of delightful terror with no moral outcome, an emotional response to the sheer enormity of this asynchronous archive of potential human histories. Broader eschatological concerns often resonate in Goffman’s whimsical universes—her totalizing aesthetic catalog may allude to one last desperate conquest of self-proclaimed world-builders: our own digital afterlife.”

It seems to me that even though your work doesn’t directly address AI, perhaps both your work and AI have found common ground in their addressing of the human condition. What are your thoughts?

I think there is a connection, yes. I have this perverse fascination with dealing with cultures of death. AI could be seen as a culture of death, in its darkest sense. There is a lack of human life, the death of work, and the emergence of a high-tech society that has a ‘lessness’ to it. But also, in these moments, these cultures of death, I have a desire to create narratives that are life-affirming.

I had a funny conversation with someone close to me recently. I was talking about how excited I was about the idea of robots living with us and working alongside us. I think robots are cute, especially if we make them look cute. The person I was talking to said: “Oh, but robots don’t exist right now.” Perhaps robots as we imagine them don’t exist right now, such as the sentient, personable, Star Wars idea of robots. But in this culture-of-death world, there is still potential for us to tell stories that are about life and the affirming of life. As part of this, I’m interested in the idea of the companion animal. This is a figure that emerges in much of my work: the dragon that is friends with the princess, or the dog as a guardian. I see overlaps here with the idea of AI as a non-human friend or companion, and this is something I will probably return to at some point. Even in anime, there is already the archetype of the half-machine, half-animal, which is starting to border on the territory of AI.

In these moments, these cultures of death, I have a desire to create narratives that are life-affirming. — Genevieve Goffman

At the same time, from a utilitarian perspective, I think AI would be a useful tool for me as an artist. I absolutely believe I have the skill set to deploy AI in useful ways, but I am also conscious that when you are working with a particular material or tool, it begins to assert itself on your work in unexpected ways. I don’t have direct plans to use it right now or in the future, but I know it is going to be something that I dwell on eventually.

Before we conclude, I want to ask you about critics. One of the intriguing aspects of your website is that you showcase both positive and negative reviews of your work: something that most architecture firms would never think of doing. Even here, there is an unexpected overlap between you and the AI world. I’m not sure if you are familiar with Generative Adversarial Networks, or GANs, but essentially it is a framework that has often been used to support AI text-to-image tools. It contains two neural networks: a creator and a critic. The ‘creator’ is tasked with creating visual representations of the user’s text prompt, and the ‘critic’ is tasked with determining whether or not the ‘creator’ has succeeded. The two networks engage in a sort of dance back and forth to ultimately create a final image that satisfies both of them. Some theorists have taken GANs as a cue to reflect on the role of the designer and critic in real life, and how the adversarial relationship is important in the generation of art, architecture, and other creative outputs.

That is somewhat of a digression, but I just wanted to demonstrate again how your work creates these interesting overlaps with AI discourse. I am more interested in your own perspective on the role of critique and critics in the creative process, and why you choose to publish negative reviews. Even beyond AI, it is a pertinent topic in architectural discourse today, with some fearing that the role of the architecture critic is in decline. What are your thoughts?

Part of my posting those negative reviews was that I found them really funny. Showcasing them seems like a funny thing to do. It also goes back to what I said earlier about the role of artists. I feel that artists are always going to be here Therefore, in a healthy art culture, there needs to be conversations about the art that is being produced. There should be criticism. Even a critic who has written multiple bad reviews of my work is essential to the art world that I exist in.

Sometimes, really stupid art is put in front of you and while everybody around you cheers it, someone needs to be the voice of criticism. — Genevieve Goffman

The danger of a culture that only supports positive reviews is that nobody will review a show unless it is positive. Does it hurt my feelings if someone leaves me a negative review? Of course, it does. But at the same time, I know that negative reviews need to exist. In some ways, this is even more important in architecture because buildings carry with them so much ideology. It is vital that there is someone out there who is scrutinizing the social implications and messaging that accompanies a piece of architecture. But it also applies to other areas. When I was in college, I remember how we were all inundated with adverts and graphic design schemes that all looked the same. The ubiquity of these styles was never something that was picked apart enough, which I think is a problem.

So, on the one hand, I thought posting negative reviews would be funny. But on the other hand, I also want us to acknowledge that, sometimes, really stupid art is put in front of you and while everybody around you cheers it, someone needs to be the voice of criticism. Sometimes it will be valid, and other times it won’t be. But it needs to exist.

To conclude, despite your many works and acclaims, you are someone still in the early part of their career. What does the future hold for you?

I can certainly see myself stepping into other modes of art, especially in my later life. I am still determined to keep narrative and storytelling at the center of my practice. Like any artist, I am always torn between wanting to make a body of work that looks completely different from anything I have ever made before and trying to hone in on certain successful things I have made. For the time being, I see myself continuing as a sculptor who works within the gallery world, and hopefully more within the museum world too.

I absolutely believe I have the skill set to deploy AI in useful ways, but I am also conscious that when you are working with a particular material or tool, it begins to assert itself on your work in unexpected ways. — Genevieve Goffman

I can also see myself building more relationships with people in the architecture and publishing worlds, and engaging my art alongside architects, writers, bookmakers, and so on. One of the most exciting aspects of working on the MAK exhibition was that it confirmed something people had been saying to be for a while, which is how compatible my work is with current conversations in architecture. That is definitely something I want to keep pursuing.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

2 Comments

"We are struggling to idealize or create a definition of our time, which by extension will define the future."

We forgot that the architecture was usually produced by people unconscious of the fact they were expressing society. That said, this work looks very interesting. It would be nice to see it blown up into real buidlings.

Informative discussion on the current mindset of the digital/AI generation - First, globally most architecture is not create by licensed architects - Second, architectural creativity and client relationships can't be taught and can't come from AI algorithms, and from my understanding AI will be able to create their own internal algorithms (programs) and this is what many are afraid of - Third, most in the design professionals and/or the client create a Program of Requirements (POR) which then an AI program can create the floor plan (layout) and elevation so that the final design can be specified by the client based on the cost perimeters in the POR - Fourth, BIM CAD programs can then create the final CD set including the structural calcs, and details - Fifth, 3D printing is extremely expensive and because of the complexity of building systems (structural, mechanical, plumbing ,electrical) I don't see it happening anytime soon - Sixth, Europe has utilized modular buildings fabricated in a factory off-site for thirty years which has internal licensed tradespeople and employs advanced automated production equipment - www.MatrixModularUSA.com if you want to take a look - thank you for a fine article ...

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.