From November 30th through December 2nd, 2022, the World Architecture Festival (WAF) held its first physical event in three years. The annual festival, adapting to an online format during the COVID-19 pandemic, is regarded as one of the most critical events in the global architectural calendar, from identifying award-winning projects from over 700 candidates around the world to facilitating debates, discussions, and critiques on the built environment, and the forces entwined within it. Below, Archinect’s Niall Patrick Walsh reflects back on his visit to the 2022 edition of the festival, held in Lisbon, Portugal.

Amid the sea of biennials, awards, and design weeks that comprise the architecture profession’s annual events calendar, the World Architecture Festival somehow remains unique. Having launched in 2008, WAF is nowhere near the world’s oldest architecture event, being more than 100 years younger than the Venice Biennale. With approximately 2,000 attendees, WAF’s visitor numbers are also far less impressive than the 480,000 visitors welcomed by the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial, or the 300,000 visitors to the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale. Operating largely away from the public audience or mainstream media spotlight shone on its counterparts, WAF is an event unapologetically of architects, by architects, and for architects.

WAF is an event unapologetically of architects, by architects, and for architects

A three-day symphony of awards, project presentations, and keynote speeches from notable figures on equally notable topics, the festival offers thousands of architects, designers, and industry specialists the opportunity to showcase their work, network with their peers, and understand the ideas, attitudes, and architectural outputs shaping the global built environment. To borrow another political analogy, WAF is as close as the architecture community can get to an annual ‘State of the Union.’

Architects tend to live in an isolated bubble, and the connection between WAF and Lisbon could open that bubble up to these other domains. ― Marc Koehler

A festival that had only operated across four host cities in its 14-year history, and confined to a virtual format during the COVID-19 pandemic, WAF marked its 2022 return as a physical event by choosing a new host city in Lisbon, Portugal. For Lisbon-based architect and event speaker Marc Koehler, the choice was fitting. “It is such an international place,” Koehler told me, alluding to the blend of European, Asian, and North and South American residents fuelling the flourishing startup hub. “I think this is the perfect setting for WAF. You meet the most interesting people from all parts of the world that have committed to wild ideas. You have artists, fintech entrepreneurs, restaurant owners, etc., and they all have a vision. Architects tend to live in an isolated bubble, and the connection between WAF and Lisbon could open that bubble up to these other domains."

In contrast to the centuries-old, undulating, cobblestone streets of Lisbon’s historic core, WAF 2022 took place at Parque das Nações, one of the city’s newest neighborhoods. Located four miles north of the city center, the once-forgotten industrial area was offered a new beginning as the site of the Lisbon Expo 1998. While the dangers of rapid events-driven urbanism were the subject of our recent feature article on Expo 2020 Dubai, fate has been kinder to Parque das Nações. Architectural landmarks such as Alvaro Siza’s Pavilhão de Portugal may hark back to its original purpose, but the area has nonetheless become a contemporary, bustling, maritime residential and commercial district for 31,000 residents, connected to central Lisbon and beyond by Santiago Calatrava’s imposing Gare do Oriente transportation hub. “You can see the amazing regeneration that has occurred in this area since the 1990s,” WilkinsonEyre director Sam Wright told me while reflecting on the area’s appropriateness for WAF. “For architects, it is an illustration of the art of the possible.”

Whether intentional or not, the hall’s composition created an apt metaphor for the modern architectural profession, and its many faces.

The festival unfolded across three days within Pavilhão 4 of the sprawling Feira Internacional de Lisboa convention center. Spatially, the 160,000-square-foot hall was arranged as two distinct wings. One wing was anchored by a long, snaking arrangement of 140+ models showcasing the works of Le Corbusier, as well as a series of tables covered in Lego pieces waiting to be assembled by passers-by. The other wing, slightly larger, was anchored by a network of stands and pavilions operated by various product manufacturers, service providers, and other AEC-orientated enterprises. One visualization company offered me the chance to win a free iPad as I walked passed their stand, which I declined. Another kitchen appliance manufacturer operated a slick pavilion with an endless supply of free coffee, which I accepted. Judging by the constant hive of activity around the pavilion throughout the festival, so did everybody else.

Whether intentional or not, the hall’s composition created an apt metaphor for the modern architectural profession and its many faces. The traveling Le Corbusier exhibition recalled a commanding profession with grand theoretical ideas for the future of living, represented by carefully-arranged models that spoke to architecture as a clinical art. In contrast to the pristine artifacts of the master builder, which one dared not approach with coffee in hand, the adjacent tables of Lego evoked a participatory process bordering on the anarchic; a free, playful, ever-changing mini skyline that perhaps resembled the bedroom or attic floors of attendees during their own childhoods. Creeping towards the ‘Lego-busier’ wing of art and free expression was a side of the profession that many only fully discover after finishing their design education; architecture as an exercise in market capitalism. In this world, spatial environments are defined as much by the specifications of commercial suppliers, brands, manufacturers, consultants, and their corporate connections with the architect, as they are by the creative aspirations of the architect themselves.

It is important that we avoid a situation where the architecture profession lives in one world, and the construction and product industry lives in another” ― Mario Cucinella

For innovative Italian architect Mario Cucinella, this presence of both architectural culture and commerce is in fact one of WAF’s strengths. “The presence of the wider industry is important,” Cucinella told me. “The reality of our work is based heavily on our relationships with materials and technologies. It is important that we avoid a situation where the architecture profession lives in one world, and the construction and product industry lives in another.”

The largest crowds throughout the festival were seen at the Main Stage, which ran a steady program of high-profile speaking events. It was here that WAF Programme Director Paul Finch declared the festival officially open on the morning of the first day and invited attendees to celebrate the opportunity to connect in person once again after a pandemic hiatus. Judging from the humble audience size within the stage area as Finch spoke, and the loud drones of conversation beyond the enclosure, most attendees did not need the invitation. “Refreshment and inspiration are the two key words I think should define the festival,” Finch told me after his speech. “I believe this should be an event where architects can forget about the day-to-day of the working world and remind themselves of why they wanted to become an architect in the first place.”

A beautiful building intensifies nothing less than the best of life’s sensibilities” ― Stephen Bayley

Following Finch’s remarks, the Main Stage played host to a range of speakers across three days. Perkins + Will’s Jean Mah emphasized the healing power of creating community and connection in healthcare settings, while AL_A’s Alice Dietsch used the firm’s Museum of Art, Architecture, and Technology in Lisbon as a vehicle for discussing the importance of human connectivity in architecture. The British writer, curator, and Design Museum founder Stephen Bayley meanwhile used his keynote speech to wrestle with the idea of “beauty,” treating the audience to a selection of one-liners that would make the cover of any architect’s sketchbook. Highlights included: “The pursuit of beauty is what defines civilization,” “A beautiful building intensifies nothing less than the best of life’s sensibilities,” and “You don’t finish a building; you start it.” Speaking to me after the event, Bayley lamented what he perceived as the neglect of beauty as a subject of conversation among designers. “It fascinates me how many ‘bad buildings’ are still being built,” Bayley told me. “I don’t know the answer. It doesn’t necessarily cost anything more to make something less ugly.”

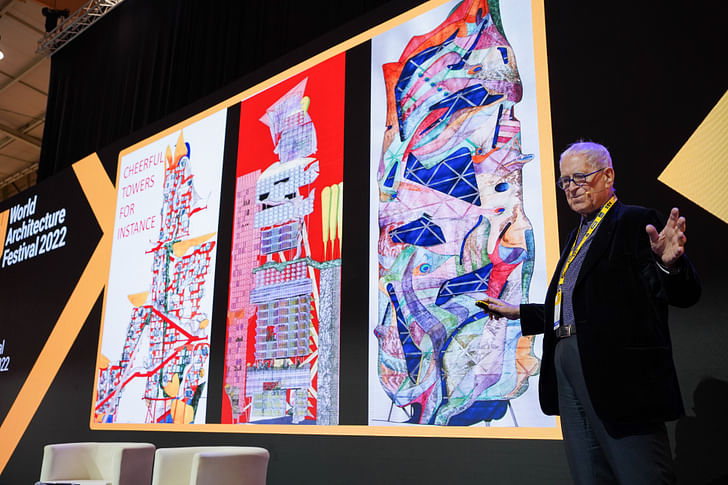

The star attraction of the Main Stage was Sir Peter Cook. The influential Archigram co-founder operated in several modes throughout the festival, as both a judge, speaker, author, and even as an architect, having designed the ABB pavilion to serve as an exclusive judges’ lounge. To coincide with the launch of his new book Speculations, Cook used his keynote speech to treat the capacity crowd to a selection of drawings that charted the course of his 70-year career; one that continuously rebels against the mundane and provokes new directions for the built environment. Though delivered in his signature conversational, laid-back style, Cook explained to me afterward the rigor behind his address. “It is by no means off-the-cuff,” he said. “I sit in the office, write it, show it to people, make edits, and was still tweaking it yesterday. Next week, I am giving the same lecture to the AA in London, which will again be tweaked. I take in feedback every time I deliver a speech, such as someone asking me a question that makes me see a line differently.”

Here, today, I get a buzz from meeting people, and what they represent” ― Sir Peter Cook

“The speech is always changing, always adapting, always responsive,” Cook added, reinforcing an outlook that has also underpinned his architectural output through the decades. After Cook’s lecture came a book signing of his latest publication, drawing a long, winding, continuous line rivaled only by the aforementioned free coffee pavilion. Walking with Cook to the festival’s press room afterward for an interview to be published on Archinect later this month, I noted that the architect must be relieved to have finally signed the last copy. “Not at all,” Cook joked. “I wish we’d brought more books!”

While the center of the hall played host to WAF’s exhibitions, keynotes, and networking opportunities, the festival’s awards series was unpacked within 17 crit rooms lining the hall’s perimeter. Within these temporary igloo-like enclosures, architects presented 252 shortlisted projects across 43 categories, grouped under the umbrella of Completed, Future, Interior, and Landscape projects. Among the constant turnover of architects delivering short 20-minute presentations, and audience members coming and going at will, each crit room housed three judges who would award a winner for all categories.

Away from the celebratory grandeur of the Main Stage, the sometimes-tense atmosphere within the crit rooms was reminiscent of the crits of many architecture schools. Architects of all personalities, from nervous and shaky to charismatic and assured, presented projects of all shapes, sizes, and uses, and just as it was in architecture school, the confidence of the presenter did not always correlate with the quality of what was presented. One remarkable difference between WAF’s crit rooms and its architecture school cousins, however, was its punctuality. Despite a heavy schedule of 252 projects presented in 20-minute cycles, the proceedings largely ran on schedule, albeit with the aid of at least one festival volunteer who, as an architect exceeded their allotted speaking time, rose to their feet holding an unceremonious sign reading ‘TIME’S UP’.

As a judge awarding the winner, you are setting a trend for future years” ― Annette Fisher

“Judging isn’t easy,” architect and judge Annette Fisher told me. “When you have the Q+A after the speaker gives their presentation, you sometimes have to really draw the intriguing aspect out of people or get them to answer elements that weren’t clear. Much of the time, the why is vitally important. Why did you make this decision? Why did you make this move? Some will answer it better than others. But in the end, we have to choose projects that will set an example and will set newer, bigger, higher aspirations for others looking on. As a judge awarding the winner, you are setting a trend for future years.”

For fellow architect and judge Amit Gupta, the most convincing presentations were delivered by those who viewed the process not as a contest but as a celebration. “It should be a big honor when people from around the world enter your crit room to see what you have done,” Gupta told me. “I like it when a person presenting is not just focusing on the jury and aiming for an award, but is addressing the audience in the room, and is offering the audience the chance to take something away with them.” Reflecting on the format of three judges selecting a winner from dozens of projects, a process which both Fisher and Gupta conceded was challenging, Gupta sees an opportunity for future editions of the festival to harness the energy of the audience.

“You might have instances where a jury is looking for particular themes in the work, such as social or contextual, but those in the audience see things differently,” Gupta told me. “In addition to a winner and highly recommended project in each category, perhaps there can be a people’s choice award. I believe some high-quality projects are missing out in the current format and, after all, architecture is for the people.”

Gupta’s sound advice of delivering a presentation not as a contest but as a celebration may have lessened the nerves of some shortlisted architects. However, other presenters I spoke to alluded to background noise outside the crit rooms as their main source of distraction when speaking. “It is so difficult to hear the judge’s questions when you are up there,” one architect whispered to me in the audience directly after they had delivered what was nonetheless a convincing presentation. Coincidentally, our dialogue was interrupted by the next speaker abruptly pausing mid-sentence, before apologizing to the room. “Sorry, I’m just trying to hear myself think,” they nervously conceded.

The acoustic distractions within the crit rooms may have been partly due to the enclosed, igloo-like environment they purported to create, an expectation of silence that only amplified the inevitable distracting drone of hundreds of conversations taking place around the festival hall. “It is partly because of the level of activity, but also because of the hard surfaces,” explained Ray Winkler, an entertainment architect who specializes in stage and performance design. “There’s nothing that absorbs the sound, so it tends to just bounce around. It’s not this festival, in particular, it is a common problem in expos.” With the crit rooms, WAF perhaps did everything possible to create a series of concentrated, intimate moments for speakers and judges while retaining a sense of fluidity, informality, and transience among the audience. But for Winkler, who counts The Rolling Stones among his clients, the feedback was ‘you can’t always get what you want.’

For regular attendees, the festival presented an all-you-can-eat buffet of architectural knowledge, ideas, and inspiration.

The crit rooms, and the awards process they facilitated, may have presented challenges for judges and speakers alike. Still, for regular attendees, the festival presented an all-you-can-eat buffet of architectural knowledge, ideas, and inspiration. The dining metaphor was made more appropriate still by the interactive screens placed outside each crit room, allowing attendees to browse the ‘menu’ of projects being presented inside. The visitor’s appetite for ideas could equally be filled by the Festival Hall Stage at the center of the venue, where highlights included RIBA president and AHMM founder Simon Allford’s update on the firm’s Holloway Prison redevelopment in London, and the community-driven Oriel Eye Hospital presented by AECOM, Penoyre & Prasad, and White Arkitekter, also located in London.

For a first-time WAF attendee such as myself, the never-ending array of keynotes, crits, and casual project updates was inevitably uplifting. However, regular WAF attendee Ole Scheeren questioned if the transition of much of the awards operations to digital screens was a step in the wrong direction. “For me, this year’s festival is maybe a great example of the conundrum of what happens when the physical tries to merge with the digital,” Scheeren told me. “In previous iterations of WAF, it was more of a giant exhibition of architecture. You walked through things, you were drawn to elements. You could see a piece of architecture at the other end of the arena and you could go and explore. Now you have to click yourself through a screen; something I can do on my iPad in an airport. Somehow, I think this shows the problem of the digital replacing too much of physical reality.”

The final day of the festival culminated with the giving of key awards derived from category winners, including the World Building of the Year, and the INSIDE World Interior of the Year. For Peter Cook, who sat on the Future Project of the Year jury, part of WAF’s appeal is the strong performance of architects and countries which don’t often feature in architectural discourse. “Countries such as the United States, the UK, and Germany often make a lot of ‘noise’ about their architecture,” Cook told me. “But they are not necessarily the ones that win at WAF. Here, you can just as easily see interesting work from India, New Zealand, China, or Ethiopia, which I have always rather liked.”

The World Building of the Year, arguably WAF’s most coveted prize, was awarded to 3XN’s Quay Quarter Tower in Sydney, Australia, a rare example of adaptive reuse brought to tall buildings. Program Director Paul Finch praised the scheme’s “excellent carbon storage” and held the project up as “an example of anticipatory workspace design produced pre-COVID which nevertheless has provided healthy and attractive space for post-pandemic users.” Meanwhile, the 2022 INSIDE World Interior of the Year was awarded to Condition_Lab’s Pingtan Children’s Library in Hunan, China, a three-story timber library that seeks to “make one aware of the social importance of architecture” in a fast-paced, commercial world.

Amid the crowning and celebration of projects built or planned, the festival also offered a moment to reflect on architecture as process rather than product. The annual Architecture Drawing Prize, the winners of whom were announced in the weeks leading up to the festival, invited architects, designers, and students to submit drawings within three categories: hand-drawn, digital, and hybrid. For Jason Parker of Make Architects, the London studio that co-launched the prize in 2017, the 2022 winners each contained an environmental undertone. Where hand-drawing category winner The Spirit of Mountain by Weicheng Ye alluded to a battle between the natural and artificial, digital category winner The wall by Anton Markus Pasing suggested a dystopian climate warning for the future, entirely void of nature. Meanwhile, hybrid category winner Fitzroy Food Institute by Samuel Wen and Michael Ren grounded itself in food and agriculture, themes central to discussions on climate, waste, and exploitation of nature.

The expectation today, when you look at an image, is that it should do something; that it should have a fourth dimension of time” ― Jason Parker, Director, Make Architects

“We are keen to maintain and showcase the connection between drawing and architecture,” Parker told me as we stood in front of the winning drawings on display in the festival hall. “In our studio, we are always trying to use drawing as a language and to communicate not only within a team but with clients. Even now, we find that clients will naturally stop and engage with a hand drawing. It still has that power.” Reflecting on the future of the prize, Parker alluded to the possibility of introducing an animated drawing category, recognizing constant evolutions in how we draw and what we as observers expect from a drawing. “The expectation today, when you look at an image, is that it should do something; that it should have a fourth dimension of time,” Parker added. “We may consider that going forward.”

In conversations with over a dozen architects across the festival’s three days and brief words with many more, the resounding message was: “It’s good to be back.” In contrast to the 2021 edition of WAF which sought to translate the festival’s program to digital space amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, the return of WAF in 2022 as a physical event brought a return to the accidental, informal, ad-hoc encounters that many attendees cherished. “It is in the nature of how our creative minds work,” architect Marc Koehler explained to me. “Serendipity is the key factor for innovation. You can’t create serendipitous encounters online. It happens in the café, at the bar, sitting next to somebody in a lecture, or debating the work afterward and discovering that the person you are talking to is doing amazing stuff, and you really share something. I meet incredible people at this event by accident.”

The pandemic offered the architectural community an insight into what a digital version of WAF could be, and for now, the community remains unconvinced.

“You can’t beat the human interface,” Peter Cook told me after his lecture. “When you are presenting or lecturing online, something happens. It codifies things. You appear in front of a camera, you don’t see anybody, and nothing or nobody catches your attention. Here, today, I get a buzz from meeting people and what they represent. I see people doing interesting work, and people introduce me to others. It’s no different from being in a bar. You meet one person, then they introduce you to another, then you meet their family. Online, things are different. You can’t help but wonder ‘who is listening.’”

More than a space to reacquaint, my conversation with Ole Scheeren touched on the power of WAF to transform careers. “I was walking through the festival yesterday, and a person came up to me and shook my hand,” Scheeren told me. “He was from Saudi Arabia. He told me that when I was on the jury for a past edition of WAF, he had presented his project to me and had won the category. He wanted to thank me for changing his life. After that award, his practice grew, and he has since done some highly interesting work. It was a moment that showed that such things can have an impact on people and their careers, and in that way, I believe the festival makes an important contribution.”

Retrospective reviews or analyses of an event do little to inform the event in real-time, nor do they offer the architectural community-at-large an opportunity to experience the social serendipity or critical acclaim that the physical WAF can so effortlessly execute.

The pandemic offered the architectural community an insight into what a digital version of WAF could be, and for now, the community remains unconvinced. There nonetheless remains a sizeable volume of architects and students around the world for whom social or geographical constraints render the current festival format inaccessible, notwithstanding the thousands of dollars many individuals would need to travel to and attend the physical WAF event. A share of responsibility for disseminating the themes, findings, and developments at festivals such as WAF undoubtedly falls on media outlets including Archinect. That said, retrospective reviews or analyses of an event do little to inform the event in real-time, nor do they offer the architectural community-at-large an opportunity to experience the social serendipity or critical acclaim that the physical WAF can so effortlessly execute. A widely-disseminated digital event is evidently not the current solution to this conundrum. So what is?

You want to use the digital where it is useful, but you may not want to defer everything to it” ― Ole Scheeren

“I think we have seen ways forward in this event,” architect and judge Annette Fisher told me on the festival's last day. “For example, many Chinese architects could not travel to Lisbon because of COVID restrictions. In the judging rooms, some of these contestants instead gave virtual presentations. There are still digital avenues such as these that could open the festival up and allow architects around the world to submit and participate without being physically in the festival halls.”

Separately, I asked Ole Scheeren whether it was possible to replicate the power of WAF in a digital format other than what we saw during the pandemic. “Maybe the answer is you don’t even want to do that,” Scheeren replied. “You want to use the digital where it is useful, but you may not want to defer everything to it. This brings us back to the lesson of the past three years. We have managed a lot of things shockingly well in the digital realm. But we can’t do everything there. I do not believe this is ever entirely replaceable.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

3 Comments

Bayley lamented what he perceived as the neglect of beauty as a subject of conversation among designers. “It fascinates me how many ‘bad buildings’ are still being built,” Bayley told me. “I don’t know the answer. It doesn’t necessarily cost anything more to make something less ugly.”

No clue what so ever?

maybe you can expand on that

I could, but so could anyone who's looked at the history of architecture in the 20th century. Just give us any opinion. I guess it's not surprising given the two quotes were posted within sight of each other.

WAF is an event unapologetically of architects, by architects, and for architects

Architects tend to live in an isolated bubble

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.