In a follow-up to our January 2022 feature on employee-owned architecture firms, we question if the Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) models which represent the majority of employee-owned architecture firms adequately fulfill a growing worker-led clamor for reform within the profession. For organizations such as the Architecture Lobby, and its founding member Peggy Deamer, meaningful worker ownership of an architectural firm goes far beyond the ESOP model of stock and retirement plans, and instead requires a fundamental rethink, or even abolition, of the employer-employee dynamic.

In A Guide to Employee-Owned Architecture Firms by Those Who Have Made the Change, we spoke with several firms in the United States and the United Kingdom on the benefits and particulars behind their decision to transition to employee ownership. A constant theme running throughout our discussions was a heavy emphasis on the financial benefits of the employee ownership model underpinning the firms, specifically an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP). Under the ESOP structure, employees who accumulate hours for the company are rewarded in the form of company stock held by an independent trustee, often paid out to the employee by the firm upon their departure.

The ESOP-structured firms we spoke to all reported worker-facing benefits to their ownership structure versus traditional partnerships or limited companies, namely an avenue to share in the company’s success, insights into the firm’s valuation and performance, and greater accountability on the firm’s management from the shareholders’ (i.e. employees’) representative trust. However, it would be a mistake to assume that an employee ownership model automatically imparts greater authority to workers to shape their firm’s direction, culture, or conditions.

To assume that an "employee-owned" architecture firm automatically grants worker autonomy, or even involvement in the running of the business, would be a mistake.

All three firms we spoke to noted that an ESOP does little to democratize a company’s day-to-day operating and decision-making structure. As UK-based Hawkins\Brown told us, an employee ownership structure must be complemented by additional, often voluntary commitments to worker consultation and representation, in order for workers to feel any tangible change from the status quo. To assume that an “employee-owned” architecture firm automatically grants worker autonomy, or even involvement in the running of the business, would be a mistake.

This misconception was appropriately demonstrated by the well-documented unionization efforts at SHoP in December 2021. In a statement following the commencement of the union efforts, SHoP cited its status as an employee-owned firm as an example of its commitment to worker wellbeing. “In March 2021, SHoP through the ESOP process became a 100-percent employee-owned company — furthering our shared commitment to a culture of innovation and the next-generation practice of architecture,” the firm said in a statement to Bisnow. However, the unionizing workers expressed skepticism over how an ESOP model would afford them a greater say in the firm's governance, pointing instead to a highly-stressed workplace rife with unpaid overtime. The unionizing effort ultimately failed in February 2022.

“You can say that ESOPs are employee-owned, but it’s far from the full picture,” said Peggy Deamer, emeritus professor at the Yale School of Architecture and founding member of the Architecture Lobby. “If an ESOP is to be paired with the term ‘employee-owned,’ then we need to make a distinction between ‘employee-owned’ and ‘worker-owned’ models.”

“An ESOP should be viewed as a retirement plan, or a succession plan,” Deamer told us. “The company puts in money that supports your retirement plan, and workers are incentivized to stay invested in the company: The more hours you put in, the more you ultimately take out. But you have no legally-enforced say in how investments are made, and it has nothing to do with your salary. It’s not ownership at all. It has nothing to do with your day-to-day work.”

This surge in interest in employee ownership is nonetheless symptomatic of broader discontent with the professional landscape.

Two-thirds of employee-owned businesses in the United States operate as ESOPs, with the remaining one-third mostly operating similar employee stock ownership models. Therefore, it is unlikely that the recent surge of interest in employee ownership in the architecture community will yield the day-to-day worker empowerment many advocates hope for. This surge in interest in employee ownership is nonetheless symptomatic of broader discontent with the professional landscape, particularly on behalf of early-to-mid career architects. “I want to believe that the spotlight is the result of pressure stemming from the unfortunate conditions within architectural work,” Deamer told us. “It would make sense that in response to more and more conversations about working conditions, wages, and rights, a firm would want to proclaim they are employee-owned. It is good publicity to at least appear like a firm that cares about your employees.”

While the aspirational “employee ownership” phrase has been hijacked by a disappointingly toothless stock ownership structure, there is an opportunity to instead consider a “worker ownership” model whose business structure is more deserving of its title. “A distinction has to be made between an ESOP-structured firm, and a firm whose organizational structure affords actual worker ownership,” Deamer continued. “In my view, that is a worker-owned cooperative. One worker, one share, one vote.”

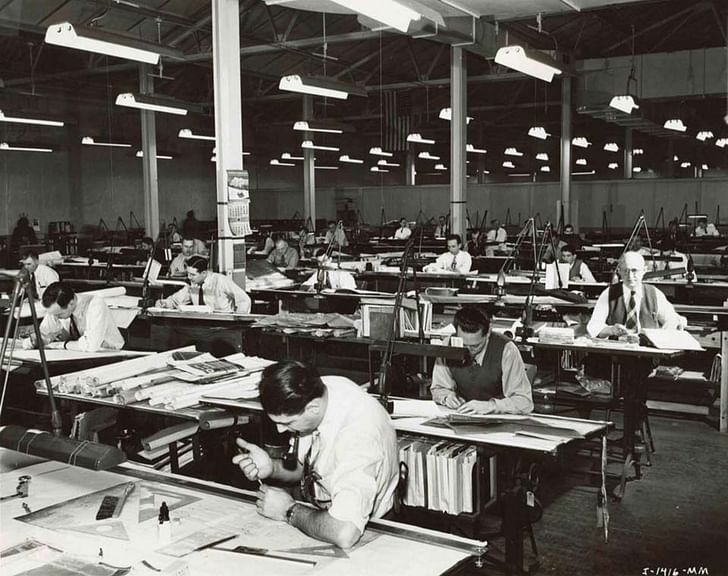

In contrast to traditional operating structures which maintain an employer-employee dynamic regardless of the existence of ESOPs or other stock plans, a worker cooperative sees each person in the company recognized as a worker-owner, participating in the profits, oversight, and often management of the company along democratic principles. The worker cooperative emerged from the United Kingdom during the Industrial Revolution, often attributed to utopian socialist and philanthropist Robert Owen who used his textile mill at New Lanark, Scotland to implement many of the values underpinning worker cooperatives.

The first recognized, successful, cooperative organization was the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers in England, 1844, whose ‘Rochdale Principles’ continue to serve as the bedrock for modern cooperatives through the updated International Cooperative Alliance (ICA) principles. These comprise:

In contrast to the almost 6,500 ESOP-structured companies in the United States, there are over 600 worker cooperatives, the majority of which were established in the last ten years, according to the latest data by the United States Federation of Worker Cooperatives (UCFWC). These range from businesses officially recognized as worker cooperatives in states which recognize the structure, to businesses such as LLCs which adhere to the cooperative definition in states which don’t recognize their status.

Since 2019, the number of worker cooperatives in the U.S. has grown by 30%, with the average worker cooperative containing six workers, and a revenue of almost $300,000. A majority (52%) of worker cooperative members are female, while just over half, 53%, identify as white. According to the USFWC, the vast majority of worker cooperatives are small businesses concentrated in the retail and service sectors, with the last decade seeing an uptake in worker cooperatives in the technology and home care sectors.

Considering that the original cooperative movement was born from the exploitative practices of the Industrial Revolution, the model may once again prove alluring for the architectural profession of the 21st century.

For Deamer, worker-owned cooperatives are a model suited not only for creative outlets such as architects but for the wider national economy. “I think it makes sense for any industry,” Deamer told us. “When you have one worker, one share, one vote, it does not mean you all have equal roles in decision making. You still have a board and a management structure. However, everyone votes on what that structure is, and who occupies the management role. You don’t necessarily need a particularly collaborative industry for a cooperative model to work: It simply makes sure that your interests are accounted for and taken care of in your workplace.”

For proponents of the worker cooperative model, the COVID-19 pandemic has also offered persuasive data on the robustness of cooperative companies. According to the USFWC, cooperatives may have fared slightly better than other businesses during the pandemic, with 20% of cooperatives losing more than half of their revenue compared to 28% of other small businesses.

Cooperatives also reported an ability to swiftly change their business models in response to the pandemic, including moving to remote working, expanding childcare options, increasing work flexibility, and offering extra sick time. As a result, 80% remained open during the majority of the pandemic, with 50% maintaining pre-pandemic operating hour levels, and 49% avoiding worker layoffs by instead opting to reduce hours or place staff on furlough. 35% of cooperatives reported increased capacity and hours during the pandemic, in order to meet demand. Finally, the pandemic also saw 60% of worker cooperatives offer resources and discounts to other cooperatives, and 73% offer discounts or resources to their wider community.

Considering that the original cooperative movement was born from the exploitative practices of the Industrial Revolution, the model may once again prove alluring for the architectural profession of the 21st century, with its well-documented and ever-more-scrutinized norms of unpaid overtime, job insecurity, and poor compensation relative to investments in time and education. In contrast, an architecture firm constructed along the principles of the cooperative movement would necessitate either equal direct management decisions by each member of the firm or a leadership chosen by, and accountable to, all members of the practice.

In a cooperative architecture firm, all profits, opportunities, and responsibilities would be shared equitably among its members. Architectural workers who decry the prison system, fossil fuels, or the military, could more effectively prevent their firm from participating in such projects, opting instead to lend their time to projects and clients aligned with their vision for the future of the built environment. Transparent, open membership structures could expose or eradicate discriminative hiring practices. Commitments to education and training could ensure that mid-to-late career architects remain at the cutting edge of software, building systems, and social and financial management. Meanwhile, early-career professionals could enjoy a hands-on, cooperative atmosphere that better equips them for their future careers, whether as sole practitioners, cooperatives, or otherwise.

The Architecture Lobby sees a cooperative network as an opportunity for small firms to share a caliber of resources currently only available to high-turnover, large-scale practices.

For Deamer and the Architecture Lobby, a cooperative movement in architecture also offers the potential for a cooperative architect’s network, where small firms could support one another via an umbrella cooperative network. Given that small firms of one to nine people represent 76% of U.S. practices, the Architecture Lobby sees a cooperative network as an opportunity for small firms to share a caliber of resources currently only available to high-turnover, large-scale practices, be it software expertise, marketing, legal or financial advice, or administrative and operational infrastructure.

Whether a cooperative network among firms or a cooperative firm among workers, an effort to introduce cooperatives to mainstream architectural business will not be without challenges. “It is hard for a professional organization, or any organization other than agricultural, to form as a legal cooperative; to have the word ‘cooperative’ in your name,” Deamer told us. “State licensing boards are not receptive to the idea of one worker, one share, one vote, to a firm composed of licensed and unlicensed members. However, there are workarounds. There are other ways of establishing bylaws and tax structures to manifest as a cooperative.”

Any group of architecture workers or firms seeking to establish themselves as a cooperative would also begin so with little precedent. While the cooperative movement in the United States has seen continuous growth over recent years supported by organizations such as the USFWC, there remain few examples of cooperatives operating in the architectural profession. One notable exception is Seattle-based Third Place Design Cooperative, the first design cooperative in the state of Washington. Under the company structure, each member has an equal vote and voice in the firm's direction, whose portfolio includes several rehabilitation and community outreach projects.

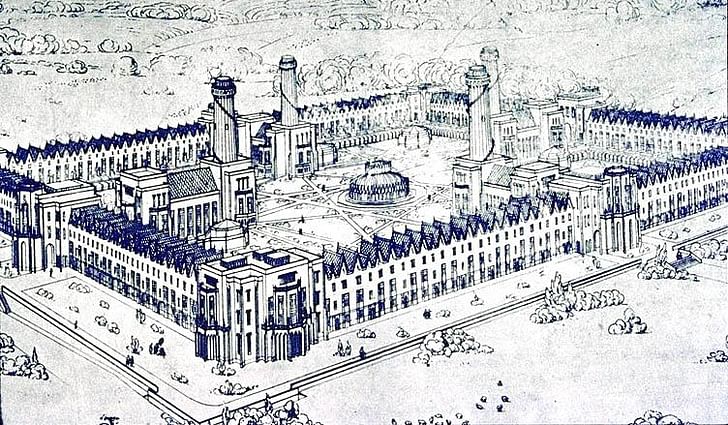

Beyond the United States, Barcelona-based cooperative firm Lacol demonstrated the potential for cooperative architects to achieve success among their peers, having been awarded the Emerging Architecture Prize at the 2022 EU Mies van der Rohe Awards. Established in 2009, the firm demonstrates the cooperative spirit through engaging with cooperative economic, social, and environmental networks, and undertaking cooperative-minded residential projects. The firm also monitors their own social, environmental, and good governance impact by engaging with the Social Balance Sheet accountability tool, under which they make a public declaration of their pay equality metrics, job quality metrics, and contributions to society and the environment.

Other historical examples include UK-based Edward Cullinan Architects, now Cullinan Studio, which established itself as a cooperative in 1972. While legally operating as a partnership, each member of the practice oversaw their own financial affairs and indemnity insurance, while all receiving a percentage of the studio’s fees and a say in management decisions.

A lack of precedent for an uncertain alternative to the status quo may no longer be enough to prevent change.

Given that only six U.S. states contain statutes regulating cooperative business entities, an architectural firm seeking to establish itself as a cooperative would, for now, likely need to establish a similar model where a cooperative structure is created through internal bylaws rather than by state legislation. In addition to chartering new territory within their profession, a cooperative architecture firm would also need to address the same USFWC-cited challenges faced by the broader U.S. cooperative movement, namely a heightened difficulty in providing health insurance, offering workplace benefits, and securing finance for business expansion.

Nevertheless, as the 2022 unionization effort at SHoP demonstrated, a lack of precedent for an uncertain alternative to the status quo may no longer be enough to prevent architectural workers in the United States from challenging, or even supplanting, the employer-employee dynamic.

As part of our ongoing explorations into the topics of labor, conditions, and business practices in architecture, we are always interested in hearing about the experiences of our community.

We, therefore, invite you to fill out our survey on employee-owned and worker-owned firms, which welcomes responses from all architecture workers, regardless of their firm's structure. You can access the survey below.

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

1 Comment

it is hard to find a more motivated and fulfilled person than that who takes part in the ethos and orientation of a firm. Work transcends its traditional role and becomes a source of pride. These are very encouraging news

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.