After decades of inactivity, 2022 saw the resurgence of the union movement in architecture with an effort by workers at New York-based SHoP to collectively organize. Where does this effort, which was ultimately withdrawn, sit within the broader discourse of architectural labor conditions? How might unionization impact employer-employee dynamics, architectural fees, and the design process itself?

In search of answers, we speak with IAMAW union organizer, and former SHoP employee, Andrew Daley, who assisted in the unionization effort while at the firm. We also speak with Peggy Deamer, founding member of The Architecture Lobby, for whom the SHoP effort was the culmination of years of activism and campaigning for reform of what an increasing number of architects see as a broken business model.

In January of this year, Vermont senator Bernie Sanders declared “our new year’s resolution for 2022 [is] to rise up and fight back.” A rare example of an ambitious new year’s resolution being fulfilled, the early months of 2022 saw seismic shifts in the unionization landscape across the United States. Coffee giant Starbucks saw nine successful union elections since the beginning of the year, spurred by the decision of Starbucks workers in December 2021 to vote to form the first union among the coffee chain’s 9,000 company-owned stores. In April, meanwhile, workers at an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island, New York achieved the first successful union organizing effort in the company’s U.S. history.

“The revolution is here,” said Chris Smalls, the union organizer at Amazon who led a walkout at the warehouse over working conditions. Smalls was fired by Amazon on the same day following the walkout, a decision which ultimately led the worker (who company executives privately described as “not smart or articulate”) to score a major milestone in the history of the U.S. labor movement.

Few corners of the American economy seem immune to this renewed union drive. In March, almost 600 tech workers at The New York Times officially unionized, forming the largest tech-worker union in the United States. One month later, MIT graduate students voted to form a union by a 2-to-1 margin, seeking to empower students who often teach, conduct research, or provide academic support for the institute.

Throughout January 2022, it appeared that the architectural profession would further add to this momentum, with workers at leading New York firm SHoP Architects expressing their intention to form a union; the first prominent union organizing effort among the U.S. architectural profession in 75 years. However, the wave broke and rolled back when, as we reported in February, the effort was suspended following a reduction in worker support. Announcing the withdrawal of their union petition, the workers (known collectively as Architectural Workers United, or AWU) described being met with a powerful anti-union campaign.

“With no existing architectural union precedent in our country, we have seen how the fear of the unknown, along with misinformation, can quickly overpower individual imaginations of something greater than the status quo,” the group wrote. “With the support of many of you, this drive has ignited a critically important conversation, both in the profession and academia. We look forward to a day when our field is no longer deeply marred by burnout and exploitation, and architectural workers and firms possess the value that we so rightly deserve.”

People want to talk about this broken system, how we can address it, and how we can potentially fix it” — Andrew Daley

For Andrew Daley, a former employee at SHoP, the legacy of the union effort at his former firm will not be its failure, but its offering of the precedent that his colleagues desperately lacked. “The first thing that has to be recognized is the courage and bravery it took for the workers at SHoP to do what they did,” Daley told Archinect. “It is an impossible task to be first.” Daley now works as a union organizer at the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers (IAMAW), an international trade union with whom AWU sought to affiliate.

As well as establishing a test case for the future, Daley believes that the SHoP effort created the conditions for a louder discussion about working conditions in the architectural profession. “Once we put this out in public, it was clear that union sentiment has been bubbling under the surface of the profession for a long time,” Daley told us. “People want to talk about this broken system, how we can address it, and how we can potentially fix it.”

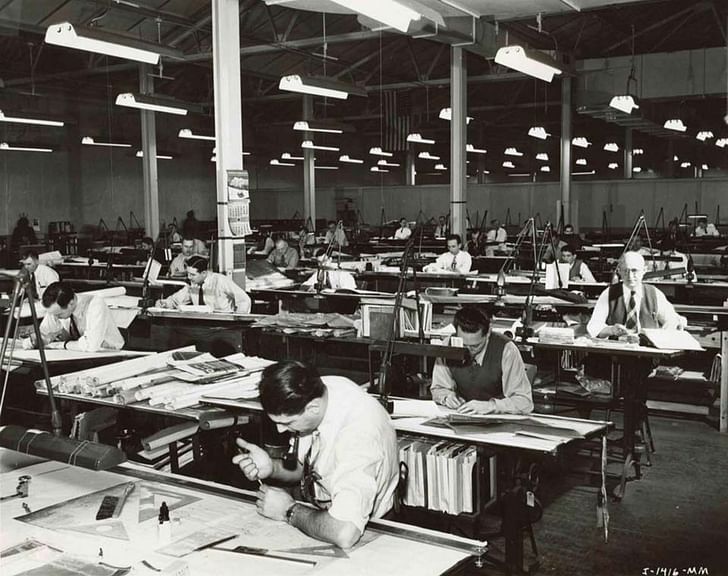

While some speculated on what the union effort at SHoP would mean for the profession, others wondered why it took so long to get here. Before the SHoP workers went public with their effort in December 2021, the last momentous union effort in the U.S. architectural profession was in 1933 with the formation of the Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists, and Technicians (FAECT), followed one year later by the alternative Architectural Guild of America.

Both groups emerged at the height of the Great Depression, garnering almost 10,000 members between them throughout the decade. The groups were not without their successes, with FAECT organizing a barricaded sit-in against the anti-union efforts of Robert Moses and securing pay raises for 7,000 architects in New York. However, both groups soon fell into irrelevance within architectural circles. While the Architectural Guild of America ultimately evolved into an organization for engineers and construction workers as opposed to architects, FAECT became defunct by 1950 at the height of the Red Scare following allegations of Communist influence over its leadership.

Architects often don’t recognize that much of their working conditions are illegal and inhumane” — Peggy Deamer

In the 70 years since the fall of FAECT, union organizing efforts among U.S. architecture firms have remained dormant. For Peggy Deamer, emeritus professor at the Yale School of Architecture and founding member of The Architecture Lobby, the reasons for this dormancy are twofold. “Architects often don’t recognize that much of their working conditions are illegal and inhumane,” Deamer told us. “There is a feeling that architecture is an art, and that architects are artists. There is a rhetoric in the profession that we are a family, and there cannot be a divorce between employers and employees. Because of this false sense of equality, architects are susceptible to being convinced they are not workers. In short, we think we are exceptional.”

Deamer’s second reason has less to do with the profession, and more to do with the wider American economic and political landscape. In addition to anti-union attacks by corporate America painting unions as a danger to workers, Deamer believes that unions themselves have historically hurt their own effort. “Unions have not helped themselves by ignoring the rank and file,” Deamer told us. “The top-down leadership has traditionally been exclusively male, doesn’t offer much diversity, and is disconnected in its actions from the rank and file.”

“When you put these two reasons together, there is a thought that unions aren’t analogous to the conditions under which architects and firms operate,” Deamer continued. “Granted, we are subject to the vagaries of the economy: we get commissions, lose them again, and popularized union conditions don’t lend themselves to the flexibility needed to respond to that. However, when workers form an organizing unit, they have the freedom to design and sculpt these conditions in response to their environment. There is no one-size-fits-all union model. The myths surrounding what union working conditions entail are in fact preventing us from having a more serious, honest look at unionization.”

In 2022 however, the world is a different place, defined by growing apathy among workers towards their workplace. While one may instinctively look to the COVID-19 pandemic as the primary cause of this apathy, its reasons are more fundamental. The past five years have seen a new generation enter the workplace: the late Millennials and early Zoomers born from the mid-1990s to the early-2000s. These groups have little reason to place trust or confidence in traditional institutions. Their childhoods and teen years saw the decay of economic institutions through a global financial crisis, of educational institutions through rising tuition fees for fewer career benefits, and of political institutions through relentless corruption, conflict, and scandal. Then, just as these generations entered the workplace in the early 2020s, a global pandemic saw their jobs, livelihoods, and many of their fundamental freedoms disappear for almost two years. Feeling exploited, failed, and duped, they are now demanding a seat at the table.

For the architects who belong to this new generation, the reasons for unionization put forward by Daley and IAMAW are beginning to resonate. “Part of the reality of the office environment is the fallacy that if you work hard, say the right things, and make friends with the right people, you will one day be in management,” Daley told us. “That may happen for some people, but the reality for most of us is that it will not. We are workers, and laborers, helping to produce capital products. If we can understand our role as workers, we can begin to entertain the idea that we need equal representation with management. It doesn’t mean you can’t become management one day. It just means that your rights and welfare as a worker are fought for.”

Employers see labor costs as their only variable, creating a nationwide profession dependent on low wages and millions of hours of unpaid overtime in order to survive.

By creating baseline workplace conditions that a firm cannot breach without consequences, Daley sees unionization as an indirect way of empowering architecture firms in fee and bid negotiations. In the United States, antitrust laws originating from the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act prohibit groups of businesses, including architects, from establishing minimum fee schedules. As experts such as Deamer have previously explored, the American Institute of Architects has been successfully sued over breaching antitrust laws. Agreements between the AIA and DOJ in 1972 and 1990, for example, restrict the AIA from taking any action to prevent individual architects from setting their own rates for work, lowering their rates to win a project, or even providing free services.

As Deamer notes, U.S. antitrust laws are so restrictive that it is illegal for two architects to agree to boycott an architectural competition or agree not to submit a bid for a project in an effort to resist procurement methods they believe to be unfair or damaging. Similar antitrust laws also exist internationally, including in the United Kingdom and European Union.

With no enforceable floor beneath architectural fee levels, firms are inevitably encouraged to lower fees as much as possible in order to win work. With other overheads such as rents, software licenses, and insurance offering little room for savings, employers see labor costs as their only variable, creating a nationwide profession dependent on low wages and millions of hours of unpaid overtime in order to survive. Where top-down baselines on fees are prohibited, Daley sees unionization (which Deamer notes is exempt from antitrust laws) as a bottom-up way of ensuring firms can no longer rely on a flexible supply of free labor. All firms would therefore be required to charge sustainable fee levels, likely much higher than those of today. “If there is a critical mass of unions within the architecture industry, conversations between management and clients regarding fees would change,” Daley explained. “Managers would be more equipped to defend fee positions due to the need to adequately provide for their workforce.”

As a case study, Daley points to the guild model employed by the U.S. acting and entertainment industry. “The guild has raised the floor,” Daley shared. “Everyone knows what the floor is, and there are expected structures in every single movie contract. Call sheets are set by the minute because producers know that if they go overtime, they lose their budget. As a result, their efficiency of hitting their contractual times is actually mind-blowing. In addition, each working actor who visits, say, 100 different shoots throughout the year is assured they get a minimum rate for being on set for a certain amount of hours.”

“Why can’t we think about architecture in a similar way?” Daley asked. “The only way to achieve that is to organize labor and say ‘this is the bare minimum we will accommodate.’ Frankly, that’s the history of unions. The reason we have weekends, federal holidays, and a standard 40-hour workweek in the United States is because of unions and organized labor. Using labor organizing as a method of setting standards in architecture is critical to how we can move the industry forward.”

There is a tremendous amount of wasted work which we pretend is part of the design process but is instead the product of poor communication and management” — Andrew Daley

With directors of a unionized workforce unable to rely on free or low-paid labor to generate profit, Daley sees unionization as a vehicle for promoting a more efficient design process. “Some projects see architects create dozens of design options, and only show three options to a client who, in earnest, probably only wants to see one,” Daley told us. “Why are we generating so much extra work? If we are contracted to produce four renderings of a project, why are we producing fifteen? Why do we sometimes resource two uncoordinated associates into a project with two differing visions, who independently instruct workers to generate drawings, models, and proposals which end up being overruled and discarded?”

“There is a tremendous amount of wasted work that we pretend is part of the design process but is instead the product of poor communication and management,” Daley argued. “If there was a financial cost to such mismanagement through overtime rates, transparent lines of communication, or a more in-depth examination of a firm’s business model, all of which would be instigated by unionization, then we could finally look with a critical eye at these issues rather than dismissing them as an integral part of the industry.”

Both Daley and Deamer emphasized to us that unionization does not happen overnight, and instead requires methodical, informed steps. The Architecture Lobby operates a dedicated unionization campaign to support the education and proliferation of unions, while Daley also stresses the importance of understanding what is required of workers and employers in a unionization campaign. As AWU (the group who led the SHoP effort) lays out on their resource page, a unionization effort in an architecture firm stems from a group of workers operating in collaboration with a union organizer, such as Daley and IAMAW, to build majority support among workers, who in-turn show interest in a union by filling out union cards.

With majority support established, the organizers can ask the employer to voluntarily recognize the union. If the union is not voluntarily recognized, organizers instead request that the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) oversees a secret ballot election to certify the union. In SHoP’s case, a petition for an election was filed to the NLRB after voluntary recognition failed. However, while the effort once held strong majority support among workers, the petition to the NLRB was withdrawn before the election could be held, after organizers concluded they no longer had majority support.

“There are lessons to be learned in how to apply public pressure when needed,” Daley told us while reflecting on the SHoP effort. “We had political support from all levels in New York City, and we want to make sure workers know that and can use it to their advantage. That is something we have thought about quite a lot after the effort.”

If the union is indeed certified, the firm’s management would be required to enter into a negotiation with representatives of the workers’ union, known as a Collective Bargaining Unit (CBU), to create a legally binding contract of employment for workers which covers wages, hours, and working conditions. Unionized workers would be required to vote to approve the contract before it is enacted, and the contracts would then typically be re-negotiated every 3 to 5 years, according to AWU.

For Daley, an awareness of the unionization process, and responsibilities of the employer, are crucial for combatting fear and disinformation. “I’ve heard people wonder why a firm owner would even want to negotiate at all,” Daley told us. “The answer is that, legally, they have to. The point of good-faith negotiation, and the inbuilt arbitration and mediation avenues provided by the NLRB, is so proposals are not made to tear down the business. The reason that CBUs are allowed access to information about how the practice is structured and financed, including information pertaining to wages, hours, and working conditions, is so unions don’t make unrealistic demands from day one.”

“There is this notion that unions have to be antagonistic and adversarial,” Daley continued. “But unions do not want to destroy businesses. We like our jobs, and we want to keep our jobs, but we want to do so in a manner that is sustainable, supportive, and fair. This is what the right to information and good faith negotiation is for.”

Even in the most liberal architecture firm, the employees are going to have to recognize that employers see unions as a threat” — Peggy Deamer

AWU’s statement announcing the withdrawal of their effort did not detail specific examples of anti-union activity by SHoP’s leadership but instead alluded to a “powerful anti-union campaign” that undermined the effort. However, recent union efforts at other corporations have offered insights into how a company’s leadership may fight unionization attempts. Starbucks fired over 20 union leaders from its stores throughout 2022, leading the NLRB to accuse the company of more than 200 violations of federal labor law during the campaigns. Discussing the firings, Daley notes that companies cannot fire an employee for engaging in unionization efforts, stressing the value of placing a union effort in the public discourse, as SHoP workers did, in order to hamper an employer’s attempts to retaliate.

Meanwhile, Amazon spent $4 million to stop the union formation at its Staten Island warehouse, including having organizers arrested for trespassing, preventing organizers from erecting campaign tents, and even rerouting a bus stop so workers would not see the union demonstrations. Over at The New York Times, publishers sought to undermine union efforts by allegedly telling large numbers of tech workers, falsely, that their position prohibited them from unionizing. The NLRB concluded that the Times “has been interfering with, restraining, and coercing employees in the exercise of their rights” guaranteed under federal labor laws.

“Even in the most liberal architecture firm, the employees are going to have to recognize that employers see unions as a threat,” Deamer told us. “This is where reading about the Amazon examples, and all the sleazy ways that Amazon scared workers away from participating in unions, is important. That is going to happen in the architecture firms, too. We cannot be naïve about what it takes.”

Daley is equally wary of how firms may respond to union efforts. “We need to recognize a reality that employers will be an impediment to this effort,” Daley told us. “They have a lot to lose, and there is a lot of power at stake. There is a lot of information that you learn about how your company is run when you vote to unionize; information that employers don’t necessarily want in circulation among the workplace. There is something wrong with the architecture business model, and clearly, those in management do not want to have that conversation at its face.”

Whether they want to have the conversation or not, firm owners may increasingly have little choice in the matter. Following decades of silence, the unionization landscape within architecture may be primed for a resurgence. Daley told us that since the SHoP effort, half a dozen groups of workers at different firms had reached out with ambitions to unionize, in addition to the two other groups who were already unionizing while the SHoP effort was underway. Daley hopes to see the results of these efforts come to fruition throughout 2022.

“People now have a forum to talk about this,” Daley told us. “Younger people entering the workforce have a different attitude to those even a decade ago. They are looking at our broken system and asking 'why are we accepting this?' and looking for ways to change not only their own circumstances but those of their older colleagues.”

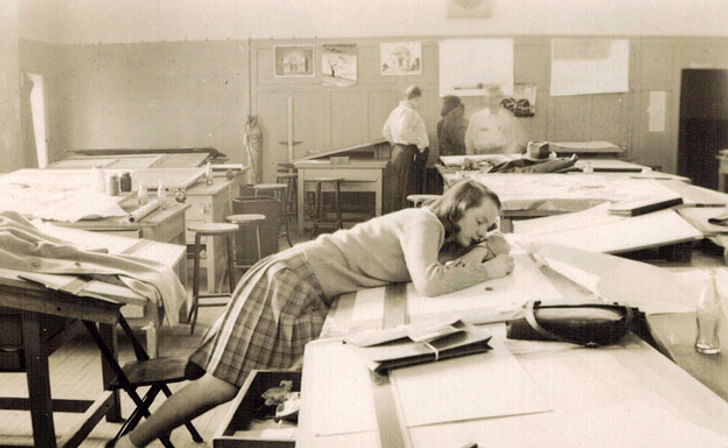

We are groomed to devalue our time and labor from day one of architecture school studio. — Andrew Daley

In tandem with activist efforts in the professional workplace, both Daley and Deamer see architectural education as a chokepoint, one which contributes heavily to exploitation within the industry but also holds the potential to end it. “We are groomed to devalue our time and labor from day one of architecture school studio,” Daley explained. “The people that spend the most hours at their work still find that there are not enough hours in the day to produce what they feel they have to. When we then accept our first jobs in the industry and put in the same amount of hours, we suddenly feel grateful just to get a paycheck. We step into that world on shaky footing from day one.”

For Deamer, the importance of reforming education was a major factor behind The Architecture Lobby establishing the Architecture Beyond Capitalism school in 2021, which seeks to educate architects to be what Deamer called “change agents” as opposed to “aestheticians simply decorating a developer’s building.”

“It’s not about teaching people just about business,” Deamer explained. “It's teaching them about how to work with the community, talk to the community, and talk to constructors so that together you can be powerful enough against developers to say 'no, that’s not how it's going to work.' We need to be able to organize a whole group of people in order for our work to have any impact on the world.”

Once you realize that you, too, are an exploited worker, just like those workers in Amazon, it’s hard to put the genie back in that bottle” — Peggy Deamer

Despite the ultimate failure of the SHoP effort, Deamer sees the attempt as a satisfying vindication of the years of training sessions, resources, and campaigns undertaken by groups such as The Architecture Lobby. Describing the effort as both “heartening” and “overdue,” she shares Daley’s optimism that the legacy of architectural unions in 2022 will not be confined to SHoP.

“I think this is going to grow,” Deamer told us. “While watching the Starbucks and Amazon workers, architects are for the first time relating these stories to themselves. We no longer read news of these efforts and see it as foreign. We are now identifying with them and saying 'this has something to do with me.' Once that lightbulb goes on, it’s hard to turn it off. Once you realize that you, too, are an exploited worker, just like those workers in Amazon, it’s hard to put the genie back in that bottle.”

Niall Patrick Walsh is an architect and journalist, living in Belfast, Ireland. He writes feature articles for Archinect and leads the Archinect In-Depth series. He is also a licensed architect in the UK and Ireland, having previously worked at BDP, one of the largest design + ...

20 Comments

So do we get a union rep that negotiates our scale wages and working conditions? - if our union demands are not met do we go on strike? ...

NB: See "B-Corporation (B-Corruption)" status for where unionisation is heading:

Fully embraced by places I'm ashamed to have worked whilst they produce corporate headquarters for Anglo American and DeBeers - both companies are the definition of corporate cartels and monopolisation. In terms of unionisation the faux concern of B-Corp status is a step in unionisation for corporate entities and should be condemned by the diversity of design disciplines.

Architects fighting over a tiny slice of pie while the AIA pseudo-union does nothing and Federal agencies put 0 dollars into architecture research and development.

it's not a tiny slice of the pie - clients/developers have plenty of money, and the construction industry is doing pretty well. architects are simply content to be the only one in the "triangle" willing to work for free.

"With no enforceable floor beneath architectural fee levels, firms are inevitably encouraged to lower fees as much as possible in order to win work."

Data to back that up? We are almost never the lowest fee on a project we pursue and our fee is rarely the reason we don't win. Most of our contemporaries are in a similar place. It may just be the clients we pursue but this seems like a specious statement that certainly is not universally true.

Has anyone done a rigorous survey on how many firms use unpaid labor?

Has anyone done a rigorous survey or research into how many hours people work on average, across a variety of firms, locations, types, etc?

Has anyone reconciled how a union would operate in a 'right to work' state (28 and counting)? What happens if a new employee to a company refuses to join the union?

What are the top conditions a union would want to fix? Specifically - what is the proposed remedy at a place like SHOP (and not just 'more work-life balance' - what does that statement mean in that context and/or what't the specific ask? that statement can mean 100 things to 100 different people.)

response to your points:

1) your anecdotal "evidence" does nothing to refute the claim, because i can tell you here in nyc it's absolutely true, and also the construction industry happens to be much better compensate due to higher unionization representation, and does not have this race to the bottom problem. further, in other industries, where offices are represented through unions, wages are at least 10% higher than comparable non-unioned offices:https://www.epi.org/press/unio...

2) anything over 40 hours (on salary) can be/is considered unpaid labor in many industries, and the majority of people on this forum recognize there are problems in this area

3) employees can "refuse to join" (not pay dues) but will still be represented in negotiations, etc. this just takes a little research to understand how unions operate

4) very vague question - part of the process is that each union is unique to its individual work place and created to address those nuanced problems. but, some of them include: unpaid overtime, shitty health care, unclear hierarchy/roles, at-will employment, hybrid work standards, etc, but generally including things that directly affect the working conditions of staff, which currently are unilaterally decided by owners/management. a union is essentially a mechanism for forcing a contract, however it might be designed, between management and staff.

hmmmmm -

somehow my edited response never went through. to recap...

Architectural fee competition for private projects is prevalent in the markets where we work. And it's not just for low-end jobs done by small firms. Big firms will totally do a job below their cost if they think they can make the money back on future work for the same client. For every thoughtful client who doesn't seek the cheapest fee, there's just as many who view architects as a fungible person whose stamp you need to get at the lowest possible price.

well, shit. for a third time i seem to be able to get the edit box up but it's not posting. if this gets through: all my questions are in earnest, not rhetorical.

i can find the gist of SHOP's asks but is there a specific list for theirs online? (the synopsis articles seem to focus on quality of life issues and hours and the reasons they believe those hours are being pushed on them).

secondly - my experiences are not being presented as 'evidence' but if we don't have any data on what kinds of firms, what kinds of projects, etc. are pushing fees to go to the bottom, how are we going to tackle that issue? 60%+ of our projects are done via a QBS or qualifications based process. many of our clients don't negotiate or look at our fee until we've already been selected (or the other winner).

not paying someone is illegal, period. report the firms to the department of labor in your state or the feds. get documentation. boycott working for those firms. better yet, no one work for them and this won't be an issue for long.

lastly... the department of labor has really clear guidelines on exemptions to the overtime rules - https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolg... - go to 22d, which covers professionals and creative professionals. basically... everyone who graduates from a college would be considered exempt. licensure doesn't matter.

.

not paying someone is illegal, period. report the firms to the department of labor in your state or the feds. get documentation. boycott working for those firms. better yet, no one work for them and this won't be an issue for long.

this is the type of attitude that is very easy to have when you've been removed of the realities of being a worker. taking these actions alone is incredibly risky, especially when your employer, who you are dependent on to provide for your very basic needs, can fire you on the spot for no reason. this is exactly what the union is for, to pursue these types of actions collectively, or better yet, preempt them together. at the very least it's incredibly logical to state that working together is much more effective than acting alone, but the owner class would have you believe you have all the power in the world to stop institutional problems in any industry, unilaterally.

but, again, i wouldn't expect someone who owns a business in this country to empathize with this... boot straps all the way!

The biggest, and most glaringly obvious take here is the ownership class, telling the worker class what they should expect, what they have a right to expect, and what they shouldn't expect.

First, there is no government mandate that unions exist. This is materially different than what is intimated. That Greg goes on to use DOL rules to establish what is, and is not permissible, as exempt employees only demonstrates what owners of companies fail to acknowledge; any rules established by a government agency, is to the benefit of the owners, and minimally to the worker. Workers by and large do not have Chambers Of Commerce, large corporations, PACs, or other lobbyists advocating on their behalf. So to ask workers to bend the knee, is absolute rubbish. Full Stop.

Second, this rancid idea, and I'll quote the entirety;

If you are a in the PMC - Professional Managerial Class - you are part of the death star. You are an owner. However, just because I may be a PM, does not make me an owner, I am a worker, and as such I will sit on the side of workers. The fact that "supervisory" is in quotes, only highlights the duplicitousness that owners enjoy.

Ownership will not dictate terms. They will negotiate terms, with workers, like fucking adults, and without government interference. This idea that built in to being an architect is moving from job, to job, type to type, and a reason for the "failing" of unionization, is an unproven counterfactual. It goes hand-in-hand with the idea that to be a good architect, you have to pull all-nighters in college, or you're not truly dedicated.

There are perhaps 4-5 firms in the US that are capable of hiring union-busting law firms, and if you think there are more than that, you are fooling yourself.

I mean seriously. If this isn't some serious horseshit. You can tell from the author that they are either an Owner, or a bootlicker. Let's see, UAW, APWU, AEA, NFL, MLB, NHL, SAG, WGAE, all of these workers made their companies, or organizations, mediocre? Loss of clients, because they value themselves, over owners? GTFOH.

Another thing, Sharples Holden and Pasquarelli, it has been demonstrated by many in other forums, are wall street thugs, and have leveraged their tremendous capital to self finance much of their work. They are not poors.

As for what Archinect posts, or doesn't post, that is a strawman if I ever saw one. We are talking the vast majority of the profession, you focus of the Starchitects. Most architects, most, will never work in those offices, and many of the offices like OMA, and others like them, are not US companies. Let's focus on US architecture firms, and US laws first, before we take on the world.

The effort to create stable labor relations, is fundamental to the future of the profession. Workers have a right to safe work environment. Workers have a right to wage transparency. Workers have a right to healthy work environment, and where egomaniacal and toxic behavior have made the workplace horrible spaces, unions can mitigate conflict and reestablish proper balance. Workers have a right not to be guilted into, or forced into overtime, any statement to the contrary is a an outright lie. I wonder how many firms actually allow their salaried staff to account for their overtime hours to begin with, as the last firm I worked for would not allow me to put any time over 40 on my timesheet. Lastly, this is a question from Greg;

Again, this is why unionization and collective bargaining are important, where the Owners think themselves in a pretzel, workers seek opportunities to provide clarity and stability for all parties involved. That's why it's called "Collective Bargaining". Just like the projects we do, the architecture we create, we don't start with answers, or solutions; we start by asking questions, and strive to bring clarity to the challenges posed by those questions, by thinking like Architects.

amen. this country is so indoctrinated with anti-labor thinking that most don't realize many of the "asks" here are standard in comparable-industrialized countries. just another example of the faux-progressive owner class being just that until any sort of change to the anti-labor status quo is proposed.

Plus, I'm not sure where shillbilly gets the idea that anyone thinks this task is going to be easy. No one ever stated that, and to suggest otherwise is not recognizing the history of labor struggle. This is going to be difficult, but it doesn't mean it's not worth doing.

Civil engineers make around 80 to 100K without all the angst and breast-beating. They start at about $63K and reach about $108K at 20 years. Don't think too many, if any, are unionized.

Um, I don't think many of them have the kinds of exploitive work environments, people, or practices either.

"hey, the pay is ok over there" is not a strong argument against unionization. there are also many more factors to consider other than pay.

I read this article, as well as Debunking Architecture’s Mythological Work Culture, as well as a similarly themed article in Architects Newspaper. A zeitgeist. Emerges. In truth, the only democratic institution in America today is a Union. As a Union member, Licensed NCARB registered architect, and LEED professional, I have never been silenced, dictated to, afraid in any Union action, negotiation, or policy decision in the conduct of union activity dealing with work, working conditions, benefits, job description, or salary. Try negotiating with Institutions like the Church, Military, Boards of Directors,etc in a upright equal manner! Unions do not stifle innovation as Owners would have us believe. Unions make products better thru standards, dialogue. About the craft of architecture and the science of buiding.Rationalization of work, methods for the conduct of the business of architecture meted by owners, is anti-Enlightenment form of abuse when the only model for work by an architect was an atelier for minding the store. Architects are way past overdue for an egalitarian makeover. The question is, "is how is an architect to validate their experience and live an authentic life? 'Neither Voluntary' participation in one's disintegration in exchange for the promise of profit sharing (if there is any) cuts it;nor recognition as master architect cut it; nor, does responsibility without authority cut it. "The only real alternative counter to market abuse is unionize architectural workers on parity with managers/owners in a full partnership dedicated to quality: quality of product, process, as well as quality of life for all architects, who deserve a discernible career path without command and control. We cannot continue the inexorably toxic atmosphere, where the parti is the pretense of the quality of the product to the exclusion of the people who create it. The best solution for me (LOCAL 21, International Federation of Professional and Technical Engineers produced the best (most ) results for the for the most people, to put it in purely utilitarian terms. It was certainly not the isolated endeavor of the other corporate/sole practician paths. Working in an architecture concern is not about knowledge and proving oneself in the antediluvian Marketplace. It is about a social construct of people, work, product, quality of environment and living limn with all these.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.