How should an architect situate their work against the natural environment? This has been a central question posed to those in the profession since its principles were first established in Vitruvius’ Ten Books of Architecture; The question has gained a unique urgency in the 21st century. Diana Agrest, a highly influential theorist and long-time professor at The Cooper Union school of architecture, is the latest to challenge common attitudes towards the built and natural environments by considering their interchangeability.

Agrest’s newest book, Architecture of Nature/Nature of Architecture, collects the student work of Agrest’s eponymous studio at The Cooper Union over the last eight years. Asked to represent geologic forces with the same attention to detail and use of tools they had otherwise ascribed to architecture, Agrest’s students have expanded the limits of architectural representation by including scales of time and space too vast to be comprehended in human lifetimes. I interviewed Agrest on the intention behind publishing the book, and how its contents may be a valuable resource to academics and practicing architects alike.

First, can you explain how you first took on the subject of Nature through the lens of architectural representation, and why you decided to develop your advanced research studio at The Cooper Union on the subject?

My interest in the question of Nature started, formally and consciously, in 1989 in relation to the city and urban form and, more specifically, to a project through which I realized that at that time, nature had been absent from urban discourse for almost 50 years. I started exploring the question of Nature from various perspectives and the result was my essay The Return of the Repressed: Nature of 1992.

Representation is essential to architectural thinking and the production of knowledge, and I have used drawing as a tool for critical exploration in my own work. Representation has always been an essential aspect of my work in both practice and critical theory and has always been central to my pedagogical approach. Knowledge can be produced by “seeing” with different eyes, not just by talking or writing, nor by photographing disaster, nor by enacting what amount to temporary “solutions” to counteract our own destructive impulse, but rather by discovering the always mutating conditions of natural systems themselves that transcend the boundaries of our own discipline. Drawings and other means of representations are tools for thought.

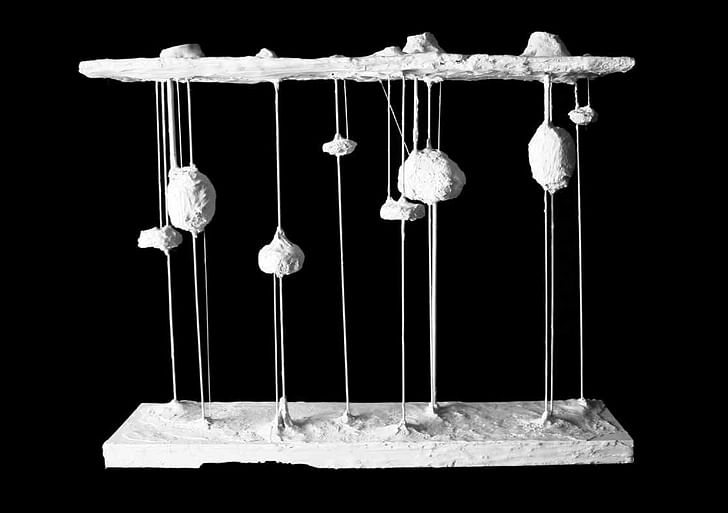

One important referent in this work is the relationship between architecture, nature, science and representation. Representations of nature act as tools in scientific discoveries. The ensuing relationship between art and science has influenced the development of scientific knowledge as it relates to the study of natural phenomena, expanded the question of the role of representation in taking nature as an object of study in the field of architecture. The work of discovery starts with the observation of extreme natural phenomena. Drawing and modeling have been used as (specific) tools that, informed by the eye of the architect, reveal a different reality. These and other tools of representation have always been and still are essential to architecture; they are tools for thought. Through them the work re-thinks the transformative power of nature in relation to the limits of our field.

How do you personally draw the distinction between "nature" and "architecture," if there is one? How do your views differ from those which led to the development of the American city, which you write "can be explained through the opposition of nature and culture, between wilderness and the city?"

Nature has played a key role in the history and theory of Western architecture, appearing as a constant motif in architectural texts from its very beginnings with Vitruvius to Alberti and all the way to Le Corbusier’s Radiant City. It is seen as a basic element in the development of architectural theory and principles, but this interaction takes a prominent position at the present moment.

Historically, however, nature has always been incorporated and embedded "within" architectural discourse. From the relationship between nature/culture to that between nature/architecture, and nature/city, nature is freed in this work from the binary sets of oppositions within which it has been defined, becoming itself the object of study changing in this way its place and articulation with our field.

In this book’s approach, nature disengages itself as a free radical from the ideological constraints of architecture, becoming itself the focus via one common mechanism essential to the production of knowledge in both science and architecture: Representation. This exploration pursues a transdisciplinary approach whereby intersections through different discourses, be they scientific, philosophical, or historical, are intrinsic to the investigation of the concepts that bear upon our own understanding of Nature. In so doing, we are expanding the very discourse of architecture itself. These discursive intersections, resulting from our readings of nature, manifest and sometimes reveal the entanglements in natural phenomena as their materiality, forces, and modes of generation overlap and affect each other.

Was climate change a common conversation topic during the first years of the research studio? How has the subject influenced the work produced by the studio over time, if at all?

One of the prevailing questions of the recent past is the relationship between Earth and humans. How many ways are there to elaborate and understand the complexity of that relationship? What is the place of humans on Earth in relation to all other living organisms—and how does this relationship change in Earth’s time-scale relative to human time? The Gaia Hypothesis appeared as one of the most significant recent ecological constructions of nature, not only in itself but also in its vast influence.

Gaia is complex, constantly transforming, and entangled systems in which humans are but one species of living organisms but not necessarily the central one. The accelerating scale of human intervention is now unprecedented, but it is not just about us. The Earth does not particularly care about us and will go on with or without us, as scientists and scholars such as Donna Haraway, Lynne Margulis, and Dorion Sagan have vividly expressed in relation to Gaia.

I would say in answering your question that this is the context within which I frame the questions of the environmental crisis we face today in relation to approaching Nature itself as object of study. This is a book for thinking philosophically about where we are.

Who are some of the architects which most influenced your study of the relationship between architecture and nature? What are the drawings which most highlighted this issue for your studies?

As I mentioned earlier, as nature has always been part of architectural discourse, since at least the Renaissance Theories, via Vitruvius. I would say that Le Corbusier brought the issue to center stage as part of his urban (then visionary) proposals, in his urban projects and texts collected in Radiant City of 1929, texts that I have criticized myself in my essay The Return of the Repressed: Nature. So, I would say that there is work in the history and theory of architecture that has been a referent that I looked at critically in my reflections on the subject, but they have not been the direct force that led me to the work I have developed in the graduate advanced research studio Architecture of Nature/Nature of Architecture, since it is a very different approach, exemplified by the type of work, and that is presented in my introduction to the book: “Expanding Boundaries: Architecture, Nature, Science, Representation,” and in the subjects of all the texts in the book, as well.

What do you believe your students gained from taking the studio, and how might it have influenced their thesis projects and work in independent practice?

My students were always incredibly inspired with the studio’s subject and approach, as they learned to think on a different key.

Rather than looking for immediate answers, Architecture of Nature/Nature of Architecture is an attempt to search for and ask what the right questions are. In that spirit, we make a parenthesis, stepping aside for a moment to take inventory and expand our knowledge and disciplinary boundaries, understanding the Earth as a living organism in its forces and complex material interactions. Focusing on the question of nature from the philosophical and scientific discourses that have explained, throughout history, the transformations that have led to the present conditions of the natural world as they affect our modes of habitation, the work explores a dimension of space, time and scale.

From this perspective nature presents a completely different concept of time. Time, as inseparable from space-time, is of a cosmic dimension that relates to the universe, taking architectural discourse by implication to a scale that transcends the disciplinary boundaries of architecture, planning or landscape.

2 Comments

if only there was a sister discipline whose core design focus seeks to answer this very question...

What is, landscape architecture?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.