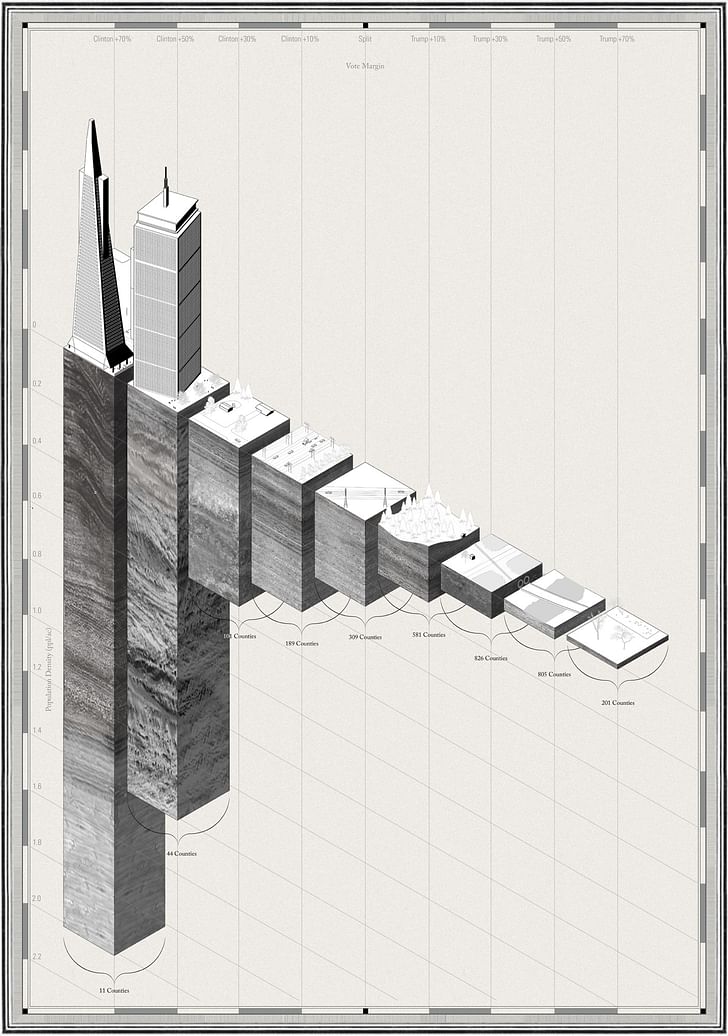

Think about the American political landscape, and a highly partisan, Russian-government-colluding version may come to mind. But what about the literal American political landscape, as defined by housing density and building typology per acre? The project “Environment as Politics: From Identity to Density Politics” by The Open Workshop, originally presented on Places Journal, studied voting patterns in the 2016 election for the U.S. President and discovered that how closely people live together may be the soundest predictor of which candidate gets their vote.

The weeks following the 2016 U.S. Presidential election yielded a cornucopia of think pieces and Op-Eds about why the country had voted the way it had.

Those counties in which people lived 216 feet apart or less tended to vote Democratic

Some news outlets blamed an emphasis on identity politics for the surprise Democratic loss, while others attributed the swing to the economic collapse of the manufacturing economy. For Neeraj Bhatia, the founder of The Open Workshop, the results seemed to be a question of density. “The New York Times published a high-res graphic of the voting results by county, which to the mind of a spatially-inclined architect, looked a lot like a chart of density values,” he explains to me. “We decided to dig into that, to explore not just what was urban versus rural, but how we even name or classify these things anymore.”

Bhatia himself is not an American, although the Canadian native found that studying the country results in detail provided a kind of frustration-relief valve for he and his other non-U.S.-citizen coworkers. They began to discern a pattern, specifically between the distance between people’s homes and their choice of candidate, with a tipping point corresponding to roughly 1.25 to 1.56 people per acre.

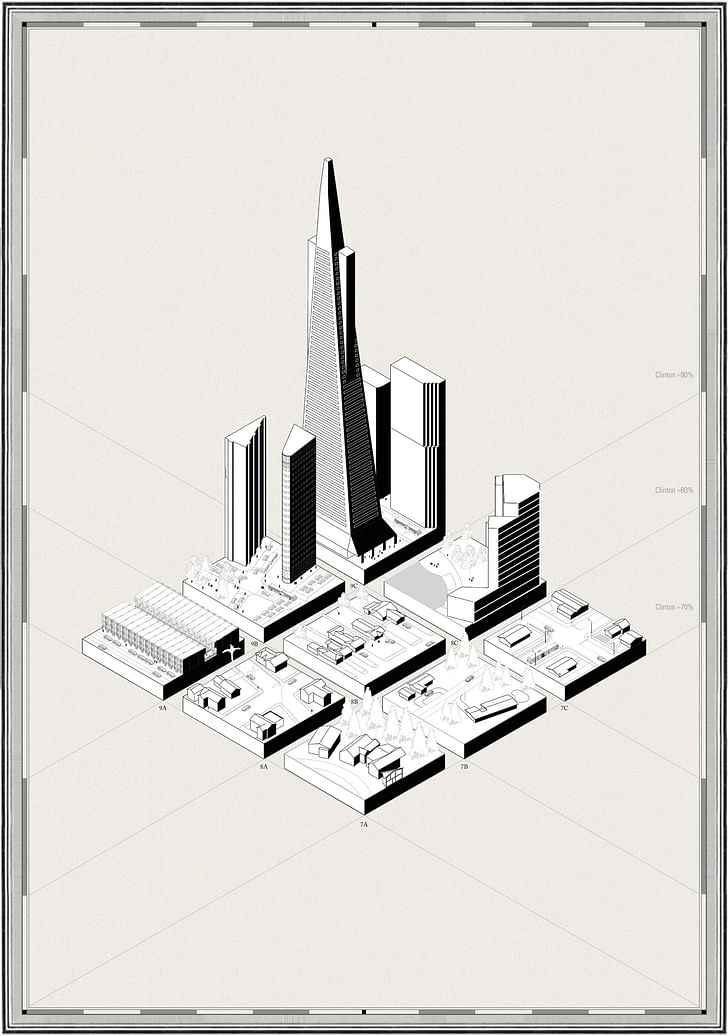

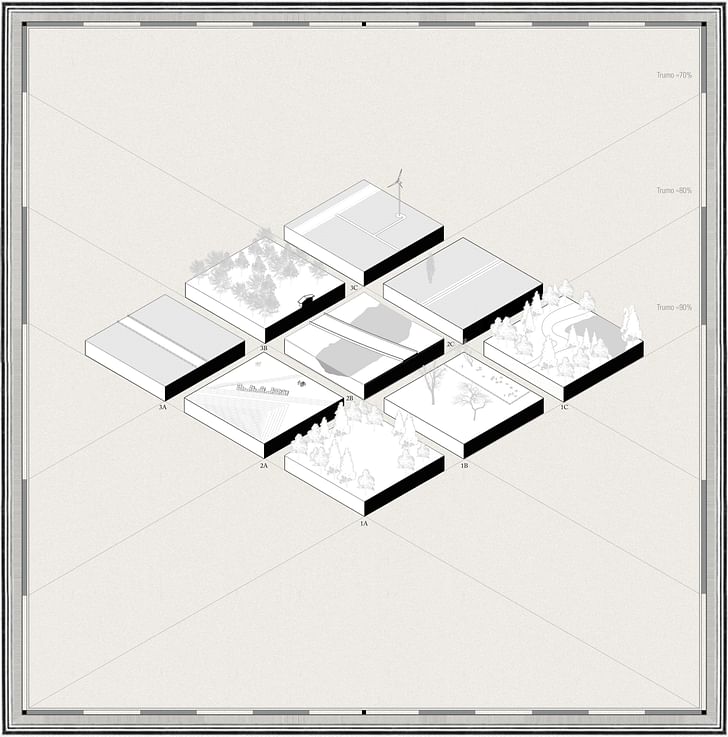

The economy with which The Open Workshop has rendered the typologies that tend to manifest certain political results is striking

Those counties in which people lived 216 feet apart or less tended to vote Democratic; counties in which the distance was closer to half a mile tended to sway Republican. The Open Workshop, using research and graphics created by Elizabeth Lessig and Cesar Lopez, decided to present these findings in a captivating image titled “Environment as Politics: From Identity to Density Politics” which is on view in Los Angeles at the WUHO Gallery until August 20th as part of the “Drawing Codes” exhibition.

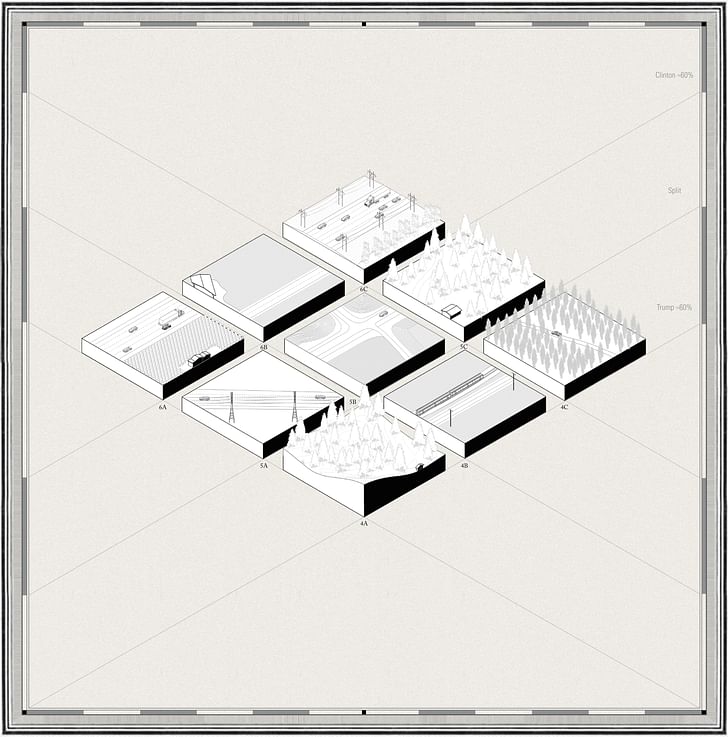

The notion of architecture as an inherently political realm is nothing new, but the specificity and economy with which The Open Workshop has rendered the typologies that tend to manifest certain political results is striking. “Environment as Politics” is presented as a grid, with population density on the y axis and the split between Clinton/Trump votes on the x axis, rendering a richly detailed acre of each prototypical county where the two points meet. A typical acre of heavily-Trump-leaning county is usually populated by a single house, or is mainly forested; an acre of heavily-Clinton-leaning county tends to sport skyscrapers. What’s fascinating is looking at the typologies of the counties that split near the middle. The mixture of developments on these split counties seems to portend a population that is poised yet hesitant about its future direction; the infrastructure of train tracks or a highway occurs more frequently than in those more heavily Republican counties, but the housing density is still fairly low.

Of course, there were outliers to the study model. Populous Richmond, Virginia voted for Trump; meanwhile the rural counties of Kenedy and Culberson counties on the Texas-Mexico border voted for Clinton. Bhatia noted that one of the Clinton-voting rural counties had a majority African-American population. However, he’s careful to qualify interpretation of the data. “I don’t want to say that’s the only reason those counties were outliers,” he explains.

Architecture and urban design are crucial to understanding how a society perceives itself

However, he notes that “you could say that our politics are a culmination of everyday interactions that add up to our lifestyles.” This notion that the physical world, as opposed to the relentless fake-news screed of the virtual one, was more influential in shaping people’s political choices bolsters the notion that architecture and urban design are crucial to understanding how a society perceives itself. The people we see every day, the way we interact with them, and the amount of distance we place between our living spaces seems to be a tremendous influence on how we process the world, even more so than photogenic pundits and click-bait headlines. I asked Bhatia if he had undertaken similar studies in other parts of the world, and he told me that although The Open Workshop hasn’t, Joe Sarling of Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners in the U.K. conducted a somewhat similar study in the U.K. in 2015, and discovered that density did seem to explain trends in political choices, with the tipping point between political parties coming at 16 to 17 people per hectacre (Labour tended to win the districts with higher density).

When I asked Bhatia if anyone, based on the results of his research, had approached him about designing a master plan with an ideal density meant to foster a specific political outcome, he laughed.

“This would be a fantastic way to get a client to design for density!” he jokes, before explaining, “We were trying to be as objective as possible. I can’t say that there’s an ideal density: I mean, we need to unpack that as a society, right? I don’t think we would want an America that has a monolithic set of values. I think what’s great about America is what a diverse place it is. It seems like there’s been very little attempt to try and negotiate and find a collective way forward, and I hope that changes.”

Julia Ingalls is primarily an essayist. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Slate, Salon, Dwell, Guernica, The LA Weekly, The Nervous Breakdown, Forth, Trop, and 89.9 KCRW. She's into it.

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.