Say the words 'bingeable television' and 'high design' in the same sentence and almost anyone will look at you like you have three heads and an even more questionable grasp on pop culture. But that’s about to change, all thanks to former Wired editor-in-chief and design consultant Scott Dadich whose Abstract series premiered on Netflix late last month. Dadich, along with co-executive producers filmmakers Morgan Neville and David O’Connor, turned the camera on the ever-illusive design process, featuring episodic biographies of discipline-spanning greats like Bjarke Ingels, Tinker Hatfield, Ilse Crawford, and Ralph Gilles, among others.

The result, an eight-part documentary whose own linearity is challenged from episode to episode, offers a grounded unpacking of what it means to be a designer working today, all the while celebrating the messiness, anxiety, failure, and joy that comes with the job. Dadich’s take is fresh, in part, he explains, because of his own experience as a designer and in part because he let his subjects take the reigns.

With Abstract, you’ve done something quite different from the typical design documentary. Why did you think it needed to be made?

I think we came at it from the perspective of the creators themselves and people who are participants in the creative process. With that kind of background there’s an awareness that it’s a messy process and it’s an exhilarating process and it’s usually nonlinear and inspiration and ideas come from strange places. For myself with a design background, and Morgan Neville and Dave O’Connor with filmmaking backgrounds, that sort of synthesis was really important to us—that it was vibrant and strange and funny and weird. We just wanted to make something that felt energetic and something that we would enjoy watching and that ultimately was how we arrived at what Abstract is today.

There are some themes that emerge in the show—the process of inquiry, seeking inspiration outside of work—that are common tenets of the design process, but there are some unusual things as well, what was most surprising to you about how these designers work?all eight of these practitioners began their design journey of every single project with a blank piece of paper and pencil

There was one thing. I have this notion about designers all having their tools and their methods but when it actually came down to it, all eight of these practitioners began their design journey of every single project with a blank piece of paper and pencil. It was sort of amazing to discover that three or four episodes in. As we had been filming and reporting and researching, we started to see this emerge with this classic moment in almost every one where the designer is like ‘let me just show you” and pulls out a piece of paper and they start doodling and sketching and drawing. It’s this really visceral thrill to understand that no matter how diverse the output, whether it’s a skyscraper or a sneaker, that act of putting ideas on paper is common to all of them.

You take some creative risks that vary in intensity from subject to subject—can you speak to this?

The process that we engaged in from casting onwards was one of engaging with our subjects creatively. Part of our ask was “you have to participate with us, you have to play, you have to be a co-creator” and for some folks, these are really busy people, that just doesn’t work. For others, that’s a dream come true. All eight of these subjects really dug in and rolled up their sleeves and enjoyed, in most cases—I think you can see from Christoph’s sometimes it’s awfully painful—this act of documenting and unspooling the stories that have comprised their lives.

In the Bjarke Ingels and Tinker Hatfield episodes in particular, the show doesn’t shy away from this truth of criticism and failure as a part of the design process, which we don’t often see—why do you think we’re not usually shown this in these neatly packaged design documentaries and why was it important for you to show it here?

I think there’s a sense in a lot of the previous design journalism-filmmaking that there’s this sort of rarification and elevation on the craft, almost in earnestness, to say ‘we deserve to participate,’ ‘we deserve to be heard.’ For me, I know all of these designers we profiled and I am one and I know how much I wrestle with it, but failure makes you better. We didn’t want to create these hagiographies falsely celebrating every aspect of these people’s lives. There are moments of struggle and there are things that don’t always work out but ultimately it is that series of challenges that makes their work better over time and is how they learn and grow. It really is an essential understanding of the true nature of the design process.

In terms of those designers working on space, the juxtaposition of Bjarke Ingels and Ilse Crawford was sort of perfect because they are so different but also share a deep understanding of human-centered design—was this intentional?

There was a sense of the scale and scope of their work and certainly their personalities lie along a spectrum of difference. I had known Bjarke longer and only recently met Ilse so I don’t think we were as acutely aware of how neatly they paired off but I was really pleased with the result and Sarina Roma, the direct of Ilse’s episode, really did a wonderful job of framing her work and influence.We didn’t want to create these hagiographies falsely celebrating every aspect of these people’s lives.

What led you to Bjarke? He’s obviously a standout for a number of reasons but there are also other architects who are working on that scale and with that grandeur.

I met Bjarke when I was the creative director of Wired in early 2008, late 2007 and he had the idea for the Yes is More book at that point and he approached me about designing it and I just couldn’t with my duties at Wired but that idea really stuck with us, that idea of saying 'yes' to all of the concerns appropriate to a project was a really interesting backbone we wanted to explore. Early on, Morgan raised his hand and said “I really want to direct that episode” because there’s such a rich vein of tension there. Certainly the relationship that Bjarke has with so much work right now, his presence and optimism around it, I found really essential to the success of this episode.

There seems to be this sudden cultural obsession with design in a very broad sense. If you go to a bookstore you see a number books about all aspects of design on the bestseller table, how does Abstract fit into this?

First of all, it’s incredibly thrilling as a designer to feel what you describe right now. There is a groundswell, almost this wave ofunderstanding that seems to be reaching so many people. Growing up in school, I never imagined that I had chosen a profession that would have such reaching influence. But I think something that’s emerging now, and this is only my theory, is that the world is moving so quickly and there are so many pieces of bad news on the front page of your newspaper or Twitter feed, and design ultimately is about empathy and understanding the human perspective, and that consideration is really fundamental to the success of design. I think people are curious about the way that the world works and understanding how those considerations manifest themselves is a really interesting tension and I wonder if there isn’t something about that below the surface.

Want to hear more about Abstract? Check out our interview with Morgan Neville for Archinect Sessions here.

Writer, erstwhile architectural historian. Currently an MBA student at the Yale School of Management.

6 Comments

Nothing is being reinvented in this series, they talk to designers, show their work and talk to people around them and some experts, just your standard design documentary. Well made though but nothing reinvented of course.

was that the goal?

Don't think so, judging from the series itself at least. That's why I just don't get the title of this fluff piece.

randomised I think the title of this post might refer to the way the designers' influence was incorporated individually into each episode of the documentary itself? Very different from, for example, the Art 21 series (which I love), which is solely images of artists at work with their own voiceover - nothing else.

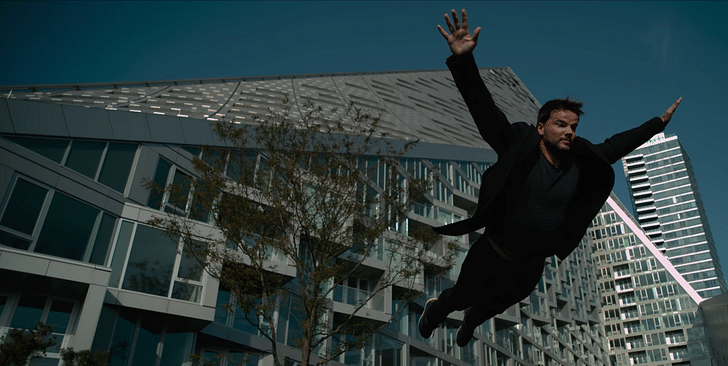

Maybe that explains why Bjarke was on that trampoline imitating the Mecanoo logo :)

to @Donna's point see this graph

Part of our ask was “you have to participate with us, you have to play, you have to be a co-creator” and for some folks, these are really busy people, that just doesn’t work. For others, that’s a dream come true. All eight of these subjects really dug in and rolled up their sleeves and enjoyed

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.