Disco architecture is a typology that makes users engage with space differently. Refracting sound, light, heat and force, they are spaces intended for excess and multi-sensory, bodily pleasure. Historically popularized by people of color, queer and trans populations, the dance floor has largely been celebrated as spaces of inclusion and sites of liberation. Yet despite this idealized legacy of disco, its spatial-politics are perhaps a more nuanced and underdeveloped terrain. What might disco have to do with the development and rhythm of the global city? Even better, what is the value of considering these types of spaces against our current political moment?

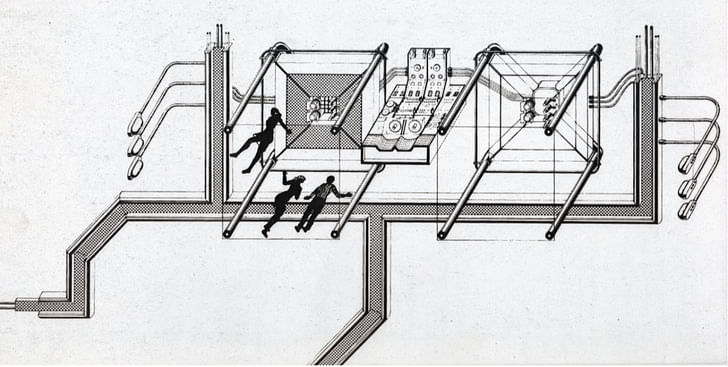

Disco can largely be categorized as a musical period spanning the mid 1970s to the early 1980s. While the musical lineage and variations of this genre are complex, as a whole, disco decisively marked the end of the 1960s counterculture, and welcomed nostalgic ideas of glamour and decadence despite an American fiscal crisis. The spaces that this type of sound inhabited are perhaps equally compelling. Structurally, disco spaces are characteristically flexible environments, designed for the maximum amount of bodies, amplified by arpeggiated rhythms, stroboscopic light, and often seemingly discontinuous, dark, mirrored environments. They are spaces of becoming, where a marginalized subject might momentarily escape oppression amongst manifold communities on the dance floor.

Temporary Autonomous Zones

Amidst the dismantling of Modernist rigidity and an emerging Pop aesthetic, Italian discos—or ‘pipers’, as they were known in Italy the late 1960s—became fertile sites of avant-garde architectural experimentation. Influenced by the writings of Marshall McLuhan and New York City’s Electric Circus, Italian radical architecture groups such as Superstudio, Gruppo 9999, and UFO saw the disco as an opportunity for innovation not only within architecture but as a medium for social exchange as well—autonomous zones free from the hegemony of normalized sociality under capitalism. Disco spaces designed by these groups were wildly spectacular, unburdened by the Modernist dictum “form follows function”. Visual projections of synthetic hues, neon light, and perforated, reflective surfaces make up the decadently nocturnal and ornamental interiors of clubs like Mach2 and The Piper, in many ways becoming a kind of architectural standard for other discos, dance clubs, and events to follow.

Yet, in a sense, the disco is really a form of temporal architecture: its dynamic key elements—light and sound—escape the concreteness that normally characterizes the fixity of the built environment. Instead, it is an architecture that exists momentarily, a form that shifts in shape, defined by its users for the night (and into the early hours of the following morning). Perhaps for this reason architect Aaron Betsky considered the disco to be “one of the most radical environments Western society has created in the last 50 years.”¹ They are spaces of radical excess, pleasure, and consumption, yet also profoundly interior. The disco, or party, aims to produce ecstatic experiences: performances that are simultaneously both public and private, allowing users to temporarily transcend the political and physical limits of the outside world—and perhaps themselves.

Spatial Practice

Samuel Delaney describes the disco as one site of “inter-class contact,”² rehearsing a now familiar understanding of the dance floor as teeming with the possibility for alternative forms of sociality. In this sense, the disco is the heterotopia par excellence, a space outside all other spaces. While Michel Foucault located the heterotopia in sites of control such as the colony, prison, or psychiatric hospital, the disco certainly might also qualify as a space for “individuals whose behavior is deviant in relation to the required mean or norm.”³ After all, it was people of color and queer bodies that not only popularized disco culture, but also found respite inside them from the racist, homophobic and hegemonic ideology of urban life. We might then consider the dance club as a space in which non-normative subjectivity was produced relationally through collective social formations. For many, the disco was a space of becoming. Yet, while the Dionysian narrative of the disco is well rehearsed, we might also consider the disco as a post-industrial site of unproductive labor. It was a site for a kind of spatial practice of self-making where a body could be mechanized by electronic BPMs, while still navigating the disciplining of a routinized, assembly line production, scored to the repetitive and mechanic pulse of Detroit techno.What is the value of queer space in an age of queer acceptance?

Discipline has always been a constitutive element of discos and dance clubs, spaces that have been regularly policed inside and outside of their urban setting, such as in New York City. Today these sites have given way to the formation of the migratory party. Unlike the concreteness of the dance club, the architecture of the party is modular, compact, portable, and nomadic. It can be retrofitted to the largest of industrial or smallest of domestic spaces. We might mourn the increasing disappearance of gay and lesbian neighborhoods and bars as the dissolution of localizable sites of community. However, we might also ask in what ways the disappearance of these queer sites is fueled not only by a phobic public sphere, no doubt exacerbated by the recent presidential election, but also by the increasing social acceptance and marketability of the LGBTQ community.* What is the value of queer space in an age of queer acceptance? Such questions would certainly need to be leveraged against the conditions of an accelerating luxury urbanism, not to mention the apps of digital cruising that have, in many cases, rendered these spaces as an expensively obsolete form of urban hardware.

Legal Bodies

It’s easy to idealize the disco as a utopian space. Without completely dismissing the significance of the intersectional character of these sites, the commonplace notion of the dance floor as a space of radical possibility might be simply an intoxicating illusion. Although the dissolving of social boundaries might have occurred inside the disco, there remains a larger question of how this dissolution became socially embodied both inside and outside of the space of disco. As Laam Hae observes, “on the dance floor, white and/or heterosexual dancers accepted and imitated the styles associated with the subcultures developed among ethnic, racial and sexual minority communities, but it is not clear how this stylistic miscegenation may have actually promoted democracy in the real world.”⁴

The politics of disco as a space of stylistic miscegenation can be usefully paired with the disciplining of the dancing body enacted through Mayor Guiliani’s revival of the cabaret laws. Originally passed in the 1920s, cabaret laws sought to regulate social spaces such as speakeasies and jazz clubs by prohibiting more than three patrons to “move together rhythmically.” As has been well documented, the cabaret laws were inaugurated as a tool for policing against racial intermingling. Though the laws loosened during the 1970s, they were once again strongly enforced by former Mayor Guiliani’s neoliberal ‘quality of life’ campaign, and further maintained under Mayor Bloomberg’s administration. The policing of trans and queers of color out of the West Village is only one historical and recurrent consequence of this law. As legal cocktails for urban development, both cabaret laws and zoning laws enact the forced eviction and eradication of many spaces of queer social life, particularly sites that cater to queers of color. In effect these laws demonstrate the city’s dismissal of the right to “democratically appropriate and produce urban space for expression, play and socialization.”⁵Queer spaces have always been sites of phobic state violence

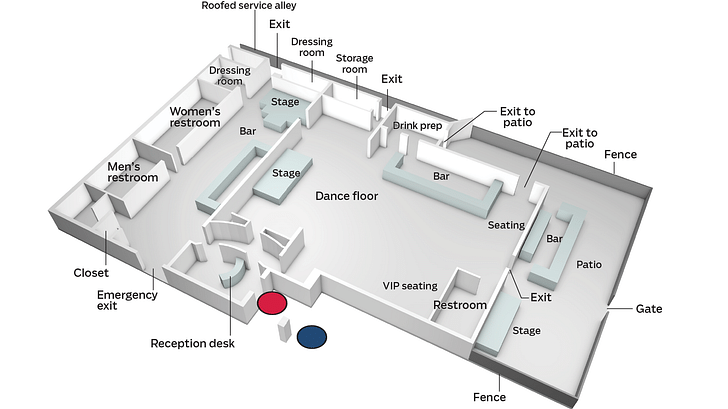

The image of the disco as a site that produces and disciplines bodies is made somewhat more somber in light of the mass shootings at PULSE Orlando, or Istanbul’s Reina nightclub. Indeed, the dance floor is often also tragic. The infiltration of the police state into the “safe” space of queer sociality, and the subsequent increases of police presence in many queer spaces throughout the United States, is a reminder of how queer spaces—from the Stonewall Inn, to Blue’s, to Atlanta’s The Eagle—have always been sites of phobic state violence, police raids, and legal enforcement. With the rise of authoritarian rhetoric driven by the Trump administration, how might we consider the dialectics of disco then, in order to better understand the ways in which dance spaces are part of an urban and legal matrix that make them localizable sites of both discipline and respite?

I ♥ NY

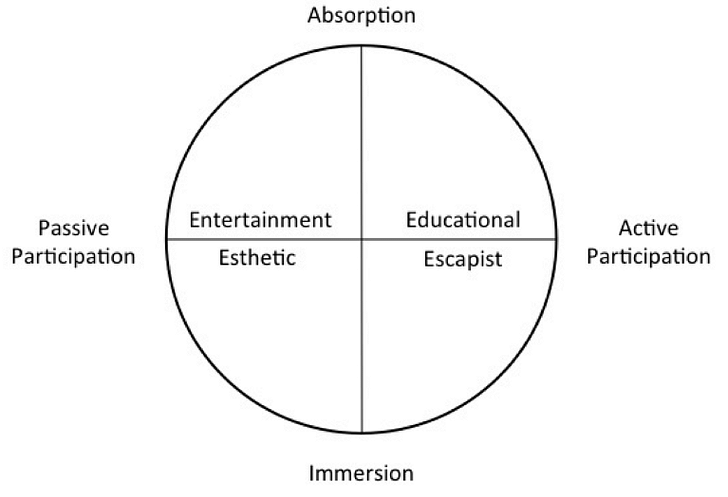

The fiscal crisis of the 1970s deteriorated the economic fabric of New York City, bringing about an acceleration of processes of deindustrialization and urban impoverishment. In its wake, however, ample former-industrial spaces were coopted by a creative class, giving rise to weekly parties like the Loft, “literally replacing industrial landscapes with their own, and thus further adding to the sense of post-industrialization in the city.”⁶ This post-Fordist condition forms the backdrop against which New York’s downtown dance scene must be considered, one that afforded the formations of communities but also new markets and foreign investment opportunities. In fact, discos might even be early examples of the “experience economy”, described by economists Joe Pine and James Gilmore. Following agrarian, industrial, and service-based economies, the experience economy is characterized as an “absorptive”, “immersive” and thematic business model that sells personalized experiences to consumers. Unlike traditionally ‘passive’ economics that surround conventional entertainment models such as the theater or symphony, the experience-based economy is driven by active consumers who “by simply being there contribute to the visual and aural event that others experience.”⁷ Consumption becomes a form of production, as cultural consumers add to the experience’s value. Through a sort of ‘managementese’ accompanied by neoliberal flowcharts and graphs, Pine and Gilmore have determined that “an experience occurs when a company intentionally uses services as the stage, and goods as props, to engage individual customers in a way that creates a memorable event.”⁸

Experience economies have been instrumental in the development of the competitive global city—and perhaps also for architecture. Considering the role architecture played in constructing the overall experience of dance clubs like Studio 54, Palladium, or Limelight, these spaces can be considered early harbingers of the turn towards an experience economy that would transform whole neighborhoods such as Times Square or SoHo. In the same way, discos developed reputations that would not only draw in targeted consumers but transport participants beyond the limits of the outside world. Along with a growing market for art and culture, disco was one of the signifiers that marked the transformation of the city from a site of industrial production to an experience economy, a condition that would help lubricate the infrastructure of experiences allowing New York to become the global city it is today.

Yet dance spaces are still regulated throughout the world by legal and market forces. In 2014 the Japanese law—fueiho—which strictly prohibited dancing without a dancing license, was lifted after several years of regulation and raids that affected both the electronic music industry as well as a night economy. Dance clubs must now keep their interiors lit 10lux brighter than before to mitigate illicit behavior. The lift in the law comes in time for Tokyo’s 2020 Olympics, ready to welcome global tourists and club-goers. More recently, London Mayor Sadiq Khan appointed a ‘night tsar’ to the “London Nighttime Commission” in response to the closure of several nightclubs-–most notably Fabric––driven by speculative property development and drug-related deaths. Recognizing dance culture as “a key driver of economic and cultural regeneration, and a magnet for domestic and international visitors”⁹ in a post-Brexit economy, the newly appointed “night tsar” will work to stimulate the city’s nocturnal economy and regulate a good business climate.disco, like so much of culture, actually aides neoliberal development

Certainly disco presages a time just before the repeatable condition of speculative real estate investment and luxury urbanism that have now swallowed places like London and New York City. However, many discos and parties occupied the spatial margins of the city that “would not only raise the value of [a] derelict neighborhood and the built environment in it, but also ultimately helped to normalize the eviction of manufacturing tenants and de-industrialization in general.”¹⁰ In this sense we might consider the ways in which disco, like so much of culture, actually aides neoliberal development. As Marxist geographer David Harvey and others have observed, cultural workers are inseparable from the neoliberal project. In New York specifically, driven by the “I Love NY” advertising campaign, the advancement of “[a]rtistic freedom, and artistic license, promoted by the city’s powerful cultural institutions, led, in effect, to the neoliberalization of culture.”¹¹ In 1978, a notoriously closeted Mayor Koch endorsed disco as the “heartbeat of what makes New York City a special place—vitality, individuality and creativity.”¹² In many ways disco ultimately became a new export, a lifestyle brand unique to New York, perfectly packaged to global tourists and professional workers.

Hacking Rhythm Analysis

If disco eventually became part of hegemonic and whitewashed neoliberal culture, its origins could not be more dissimilar from this end result. Observing disco’s relationship to a capitalist mode of production with subversive potential, Richard Dyer noted in 1979 that “the anarchy of capitalism throws up commodities that an oppressed group can take up and use to cobble together its own culture.”¹³ Dance culture is filled with sneakier examples of resistance that go against self-righteous forms of activism. For instance, though the Loft maintained a concrete physical location, it was only accessible via an invisible spatial network of social capital. Access to the Loft was granted by invitation only—a result of one’s proximity to David Mancuso. However paranoid, Mancuso’s insistence on the party remaining a private event rather than a club constitutes a legal hack that allowed the Loft (and other similarly exclusive downtown parties) to function without liquor or cabaret licenses. This was also true for many NYC gay bars, a number of which were owned in part by the Mafia, which granted these early queer spaces a form of vigilante privilege and exemption from the law. Though today questions of exclusivity and exclusion are often framed as a privilege of the wealthy and elite, perhaps there is something useful to be recuperated and learned from these legal hacks. Amidst a rising luxury urbanism that has challenged the building of subcultural community and non-normative sociality, in what ways can we rewrite the code that programs the dominant operating system in which we find ourselves today? How might we effectively use “dance as weapons”?That a real-estate developer trafficking authoritarian rhetoric was elected President of the United States of America should perhaps not come as a surprise. Yet, in a moment when so much seems at stake, in what ways might we look to the eccentricity of dance culture as a prototype for creating forms of community that resist the hegemonic and white-washed standardization at work today. How might we effectively use “dance as weapons”¹⁴ to combat an increasingly racist, homophobic and transphobic public sphere? Given the recent speculation surrounding the hacking of our own democratic software, as well as the planned construction of border walls and environmental enclosures, it is no longer simply the law which must be hacked, but the very architectural and spatial logics of urban development and policy. Maybe it is disco, after all, that might serve as an example to rewrite the code and build an architecture of inclusion. The dialectical space of the disco perhaps affords some clues in proposing an open-plan to “move together rhythmically”¹⁵ and shake the habitual development of urban life.

* As Christina B. Hanhardt observes, “in the 1970s, popular acceptance of homosexuality had grown, and realtors began marketing gay people as the ideal tenants of changing neighborhoods, focusing especially on middle-class white gay men as high-earning, risk-taking, and family-free”. See: Jordan T. Camp. Policing the Planet. 2016. Verso. Page 45.

1 Comment

MOAR

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.