The call for the 15th La Biennale Architettura di Venezia, “Reporting from the Front,” asked architecture to give a damn. It did so as an expression of dissatisfaction with past performances, and by attempting to showcase remedies, all under the curatorial leadership of 2016 Pritzker Prize winner, Alejandro Aravena.

Biennale President Paolo Barrata, in his official event announcement, identified in previous exhibitions a tendency to “deplore the present” as “characterized by increasing disconnection between architecture and civil society.” Aravena, in turn, extended his personal interest in building as a channel to the improvement of lives into a prompt for the promotion of architectures on the edge and reaching out. He charged this year’s Biennale with opening up—both architecture and its exhibition practices.

This effort to cultivate a momentum for architectures redefined by extenuating circumstance—swept away by culture, economy, environment, politics, etc.—drew, on a number of fronts, instant fire. In his positioning around “architecture [that] did, is and will make a difference,” Aravena, in his curatorial statement, seemed not only to designate such architectures as anomalous, but to delineate bounds for what impactful architecture is. He implicated a particular realm of struggle as a qualifier for architecture’s broader relevance.

the negotiations that accrue into architectures may not themselves be architecture.Reading the call as either invitation or provocation, however, the sixty-four national participants in the Biennale, each responding through their pavilions, upend any such notion of exceptionalism. In a spectrum of (mis)interpretations and confrontations, the world makes clear that there is no one way for architecture to do or care. The inconsistency and individuality throughout the many contributions to the Biennale demonstrate an indisputable complex of energy and passion and, in fact, lay out a multi-pronged argument against the universalizing architectural agenda—regardless of the shape it assumes.

Running with It (Sort of): Even Aravena’s stereotypical front has nuance.

Not everyone took issue with the emphasis on problematizing or the social outreach of “Reporting from the Front.” Indeed, a majority of the projects reflect some embrace of, or spin on, these concerns as representative of the very real conditions influencing local architectures today.

The Mexican pavilion, for example, reinforces an appreciation of the built environment as a resultant of communal process, under the headline declaring that “Architecture does not solve social problems. People working together solve social problems.” At the same time, it acknowledges that the negotiations that accrue into architectures may not themselves be architecture. It simultaneously estimates Aravena’s sweeping view as both vital, and peripheral, to disciplinary discourse.

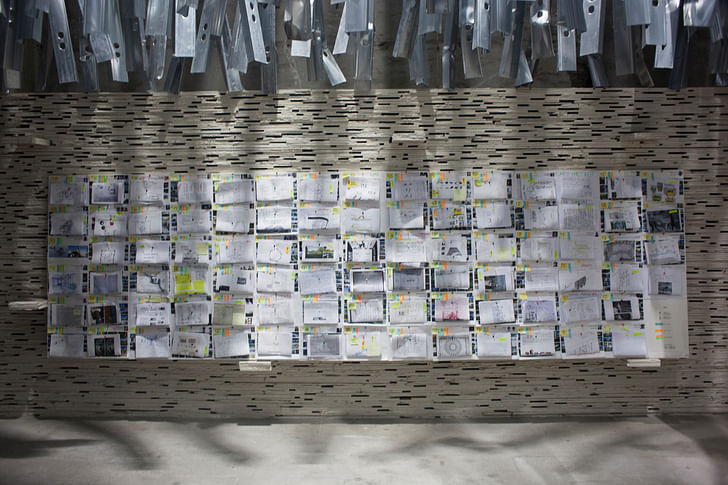

Regardless, Mexico’s “Despliegues y Ensambles | Unfoldings and Assemblages” sympathizes with the “Reporting from the Front” inclusivity mandate. It is the outcome of a quest to draw out under-knowns and to distribute the power intrinsic to architectural and engineering know-how. In a cross-country road-trip, curator Pablo Landa embarked on a mission to recognize the Biennale presentation reflects the kind of messiness that typifies the initial stages of transition and self-reinvention.and bolster the vernacular and participatory architectures that quietly, but overwhelmingly, make Mexico. “We were looking for experiences that could be multiplied, thinking of systems—not one-offs,” Landa says of the thirty-plus projects that emblematize the findings and provide the exhibition content.

Distilled into lessons, the example collection aims to convey procedural strategy and construction quality in mass. Corresponding to and elaborating upon Biennale display didactics, an online database adapts a national legacy with instruction manuals to the digital era. By breaking down the steps behind the featured works, it provides a resource for greater independence and sophistication in Mexico’s fabric. It also attempts a reorientation, through the social, back to architecture, to the crafted building.

Urbanism’s Sympathies: The front falls inside allied disciplines.

Germany—by cutting substantial holes through the facades of their permanent pavilion—uses one grand gesture, a symbolic act, of affinity for a frontline vantage. “Making Heimat. Germany, Arrival Country” is a literal and figurative opening up—and reference to the nation’s fluid border stance.

Otherwise a reaction to the radical population shifts precipitated by the ongoing European immigration crisis, the German contribution discloses a grappling with unfamiliar informalities. The remaining bulk of the Biennale presentation reflects the kind of messiness that typifies the initial stages of transition and self-reinvention.

Space within the punctured hall is allocated by eight groupings of text, inspired from urban theses in Doug Saunders’ book, Arrival City: How the Largest Migration in History is Reshaping Our World. Rough and colorful graphics accompanying the materials, showing national data and immigrant community case-study profiles, are reminiscent of grade school billboards. Everyday objects—lawn chairs, charging stations, benches and tables made from stacked boards and bricks for closing up the walls at the Biennale’s end—also are scattered around the pavilion, encouraging its use as a free-access hub.

These hand-crafted and mass-produced furnishings conform to “an explicit adoption of the aesthetics of expediency prevalent in the refugee neighborhoods,” exhibition architects Elena Schütz and Julian Schubert explain. The duo behind Berlin’s Something Fantastic posit the pragmatics as both liberating and empowering. The ease and comfort around raw and prevalent goods, for them, facilitate the hard-to-translate concept of heimat: an active version of home or belonging as projected and then created by the inhabitant.

The German exhibition is one of either pre- or post-architectures. From this state of unsettlement, the call for redefinition within “Reporting from the Front” fits. It is one that accommodates inquietude with architectural fixity amidst the uncertainty of moving parts. It enables an intercession of urbanism—wherein the logics of information amassing and analytics become the component tools to frame an infrastructure for future planning, and future architectures.

A Defense of (False) Binaries: The front dilutes the canon; the canon disaffects the people.

The United States' contribution is caught in a showdown between advocacy for the skills, bodies of knowledge, and perspectives unique to architecture, and for the forces inside which those disciplinary claims live. While the pavilion installation comes across as “architecture as usual” (a collection of wall-mounted visuals and pedestaled scale models), activity leading up to and encircling the show betrays the attempt at a unified front.

Through twelve proposals for four sites in Detroit, Michigan, “The Architectural Imagination” advances the speculative as the instrument of societal uplift. Submitting wild thinking as the means of igniting change, it taps into The Motor City’s history with innovation to engender excitement for new ventures:

Pita & Bloom adopts the outlines of an old city masterplan and the profiles of existing landmarks into three-dimensional contours for the shell structures of Detroit Mexicantown’s pop-colorful “The New Zocalo.” BairBalliet plays with scale, exaggerating details into pavilions and shrinking monoliths through surgery and illusion, in a post office redistributed as “The Next Port of Call.” MOS’s “A Situation Made From Loose and Overlapping Social The real protest, though, might be that disciplinary discourse continues to be dominated by the black-and-white pendulum swingsand Architectural Aggregates” fantasizes about architectures free to roam in the vacancies of the Dequindre Cut. T+E+A+M rebrands decay as resource by turning the abandoned Packard Plant into the “Detroit Reassembly Plant,” a material processing facility that alchemically reconstitutes old buildings into new architectures. All of the proposals take a stand for the generative potential of distance from reality and the inspirational power of the image.

But, as Cynthia Davidson, co-curator along with Mónica Ponce de León, acknowledges in her cataLog introduction to the exhibition, “There will be those in Detroit who are disappointed in the results of ‘The Architectural Imagination’ because they offer no concrete solutions for a city beset by real problems, at a time when ‘problem solving’ has become the mantra of a new social agenda for architecture. Let me state clearly that we never set out to solve specific problems. The projects produced for the sites in Detroit propose powerful ideas and architectural forms that will seem both liberating and alien, intended as they are to challenge the status quo and raise it to another level.”

Sure enough, the Detroit Resists digital occupation of “The Architectural Imagination” counters the US pavilion’s spin on Aravena’s brand of social agenda with an inverse protest. The activist coalition’s co-option is a kick-back to the political and circumstantial. The speculative, the resistors argue, not only is a luxury of privilege, but a slight to and whitewashing of the lived architecture’s everyday builders and residents.

On the one hand, then, there is a rightful attempt to represent architecture, the art, to hold up its particular (civic) value. On the other, there is a cry for the present to be seen, to be recognized as and within art. The real protest, though, might be that disciplinary discourse continues to be dominated by the black-and-white pendulum swings between these two marginalized extremes, that the conversations that might raise up both sides get skipped over in the polarity.

Both / And What front? Architecture and cultural production are intrinsically entangled.

Denmark, both a design heavyweight and a social welfare state, scratched their collective heads at the novelty implied in the call for architectures for the public good. “Architecture depends on frameworks of political and institutional power; culture depends on architecture to reimagine manifestations of democracy,” co-curators Boris Brorman Jensen and Kristoffer Lindhardt Weiss insist with an “it-just-is” nonchalance.

There is a given reciprocity between the eloquent design move and the elevation of the human condition in the Danish tradition. It is a mindset that incorporates both aestheticism and ethics. “Architecture is the answer to the urgency [expressed in Aravena’s call],” the co-curators continue. “It is what solves social issues and challenges.”

So confident in the ability of their nation’s everyday architecture to adhere to humanist principles, Jensen and Weiss deliberately took all leading statements out of their internal call for pavilion participants. They simply requested submissions of architecture projects recently developed from firms across the country.

A funhouse of aesthetic, representational, and communication approaches“Art of Many,” a wunderkammer of working models of the 130 building representatives selected from the unrestricted inquiry—including BIG’s The Mountain, 3XN’s Ørestad College, NORD Architects’ Marine Education Center, AI’s Public Housing Affected by People, and ADEPT/MVRDV’s House of Culture and Movement—takes up one half of the exhibition. The other half, “The Right to Space,” is a video tribute to urban design luminary, Jan Gehl, in his 80th birthday year. The two-part presentation, elaborated upon in a supplementary slow text, offers a celebration of the dependencies between the well-crafted and the well-meaning. In so doing, it suggests a cohabited alternative to the partitioned practice of architecture.

Ideological Fallout: The front can collapse the center (and vice versa).

“A sad consequence of the famous Resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Council of Ministers of the USSR ‘On eliminating superfluities in design and construction’ (1955) was the marginalization of a whole range of crafts linked to the construction industry… The present exhibition is a tribute to a culture which is no longer; it is also at the same time evidence of the resurrection of craft traditions which it might seem have long since died out in Russia.”

As set up by its wall text, the Russian pavilion, “V.D.N.H. Urban Phenomenon,” is a fantastically bizarre reminder of the histories and consequences of conflating ideology, culture, and architecture—or of suppressing one for the other. Dedicated to the many lives of the V.D.N.K.h., a 780 acre theme park of nationalized education and recreation, the exhibition tells a tale of tug and war between the carriers of the complex’s civic agenda: “content” and “form”—the terms into which Leo Tolstoy, in War and Peace, divides all phenomena of existence.

A funhouse of aesthetic, representational, and communication approaches, the pavilion portrays the V.D.N.Kh.’s century of alternating biases between the conceptual and the physical. In distinct atmospheres—a digital black box becomes sculpture gallery becomes multi-media surround becomes contemplative halls—each alluding to a radical swing in the role of the 1939 landmark, the battle for primacy between the forces and tools that determine quality of life plays out on technicolor loop.

The Real Dark Side: The front is a facade.

Romania’s “Selfie Automaton” slyly exposes the inextricable encroachment of any (public) design project onto the slippery slopes of social engineering. Using an absurdist aesthetic, polished but reminiscent of 19th century caravans and circuses, the exhibition is a distributed series of sets, seven interfaces between visitors and marionette stagings. Mechanized wooden puppets—tied to the stirring, pedaling, and cranking of their human counterparts—responsively dine, dance, debate, perform.

“Even though constructed with the necessary joints that would allow them the ‘freedom of movement’, the wooden puppets are unstrung and literally nailed into a mechanism that allows them nothing but one predefined repetitive movement. And the visitor,” the exhibition statement warns, “is no exception.” Locked in a reciprocal exchange of reactions, animator and animated work to instill discomfort with and stimulate doubt in cultural constructs.

Too Big to Fail: The communal front has nothing on the global front.

“Extraction,” Canada’s pavilion in the Biennale, is an exposé of the country’s imperial mining practices worldwide. The project, operating at the 1:100,000,000 scale of resource acquisition and land-forming, introduces the ultimate architecture, or architectures so extreme that all others are superseded. The emphasis on such incomprehensible magnitudes—those with universally apocalyptic potential—sidelines, if not shames, the anthropocentric.

Taking on not only the governing institutions sponsoring the exhibition, curator Pierre Bélanger and his production team overcame “a list of every possible bureaucratic, logistical, and material blockade imaginable multiplied times three” in order to participate in the Biennale and turn attentions to the really big issues. With their permanent pavilion closed for construction and an agitator’s stance, Canada brings the fight.

The outdoor exhibition, a sub-surface video projected through an underfoot oculus, converts homelessness into an advantage through its territorial claim of the Giardini’s “power ground,” a prominent location halfway between the British and German pavilions. From this exposed but subtle lookout, the intervention subverts Aravena’s prioritization on improving quality of life, pointing out—to anyone who will bend down and look through the portal—the cumulative impacts of society’s strivings towards conventional consumer dreams as environmentally catastrophic and ultimately self-defeating.

Survival Guide: Architecture is pre-front.

“ELABORATE HIDDEN TUNNEL DISCOVERED UNDERNEATH THE URUGUAYAN NATIONAL PAVILION. Inside thousands of properties collected from other national pavilions with enough items to fill another exhibition.”Architecture, fundamentally, is whatever it takes to divide life from death. It is a vital brutality.

News pamphlet headlines and the odd sightings of poncho’d agents sneaking around the Biennale’s grounds announce the performance that is “Rebootati,” the Uruguayan exhibition. Follow the props and actors to their source and, at the choreography’s origins in the national pavilion, is a hole drilled through the concrete floor. The comings and goings of the disguised figures lead then to an adjacent cordoned alcove wherein “officials” bag and tag a growing trove of appropriated goods. These co-options, once prepped, will journey to Montevideo (through the tunnel?) to reconstitute a Frankenstein of the Biennale in a context beyond its customary reach.

Sketched on the walls of the otherwise Spartan space, depictions of marooned survivors in extreme environments hint at the message of the Uruguayan’s clever ruse and commentary. “Arquitectura o muerte,” a label declares. Architecture, fundamentally, is whatever it takes to divide life from death. It is a vital brutality.

Subjectivities: It’s all in your head.

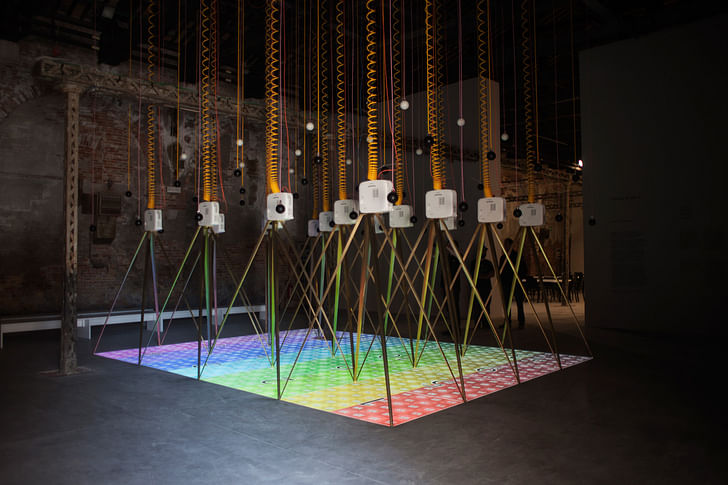

Ireland’s “Losing Myself” upends all concerns for the orientation of architecture by assuming the disorientation of dementia. Through its situation within an unraveling of reality, it reveals the conceptual and the physical, the social and the formal, as little more than cognitive processing. Everything disintegrates with the mind.

Niall McLaughlin’s and Yeoryia Manolopoulou’s Alzheimer’s design research is one part media presentation of confused and fragmented orthographics, emanating from an infrastructural grid of projectors, and one part website. Their challenge of the expectations for both the lived experience and its representation establishes architecture as conditional, a mere perception.

Beyond the individual pavilions, the success of “Reporting from the Front” is its ability to generate a platform not only for its own interests, but also for the arguments against it—precisely thanks to the inclusivity for which it is questioned. The (oppositional) substance of many of the national contributions clearly registers a multitude of ways in which architecture always/already gives a damn. These assessments also draw out many of the flaws inherent to any “do-good” mandate. But, it seems, post-production observers still deliver the most obvious critique.

A diversity of projects, in other words, does not amount to a diversity of voices.The Biennale’s opening panel, “Meetings on Architecture: Infrastructure,” instantaneously betrayed Aravena’s diversity ideals as pretense with its all male line-up. The photo snaps of eight demographically homogenous men sitting on a stage triggered an indignant outcry. The online protests that ensued made obvious the limitations of the “Reporting from the Front” infrastructure.

Similarly, it took external (social) media to show concern for the labor inequities that shadow the architecture discipline. Both The Architecture Lobby, with the launch of their book, Asymmetric Labors: The Economy of Architecture in Theory and Practice, from the New Zealand exhibition, and @BirdsofVenice, a satirical Twitter feed of running reactions to the Biennale experience, brought some exposure to the invisible, un(der)paid armies who make the Biennale and its feeder architectures possible.

A diversity of projects, in other words, does not amount to a diversity of voices. Indeed, in his 1983 essay, “’The Indignity of Speaking for Others’: An Imaginary Interview,” art critic Craig Owens pulls from philosophy into the creative disciplines the concept that “to represent is to subjugate”. It is in this context that Aravena’s call and its representations stand out—as fronts, not only for the subjects of the Biennale’s architectures, but also for its agents—for the exclusivity still deeply entrenched within the discipline.

So, while this year’s Biennale may, however inadvertently, capture a relatively thorough picture of the issues defining the contemporary architecture scene, it also exposes just how very far away the acceptances of these pluralities—perspectives and people, alike—are. For a field dedicated to the making of space, architecture has an unusually hard time making room.

For extended coverage of the 2016 Venice Biennale, check out our News and Feature stories.

Andrea Dietz is an architect/designer with Chu + Gooding Architects, a Los Angeles-based office with an emphases on cultural projects and exhibition design.In 2015, she concluded the 5-year management of a $2.8 million federal award that supported the launch of the graduate architecture programs ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.