The housing crisis in London has rumbled on for decades, its supply never quite catching up with the demands of its own population growth. Council stock has been sold off without being replaced, creating an un-developable green belt around it – a victim, in part, to its success as a hip, modern, international financial centre, and purveyor of “Olde Worlde” charm.

However, London is also regenerative. All 8.6 million (and climbing) in the city are seeking answers to how we can solve the housing crisis.

In June 2015, New London Architecture (NLA) launched New Ideas for Housing London, a competition that aimed to provide a variety of solutions to the current crisis, in partnership with the Mayor of London, Boris Johnson. Winning entrants would then work with the Greater London Authority (GLA) to see how their ideas could be put into practice. This, of course, is what marks out this competition from a more distanced, cerebral approach: working with politicians is the ultimate task to be performed going forward.

Currently at a committee hearing in the House of Commons, the Housing and Planning Bill 2015-16 aims to change the definition of affordable housing to include not just properties for rent, but starter homes as well. This provision will mean developers will be able to fulfill their obligations to a council by building homes for purchase.

The bill would require councils to “sell the top third of their most valuable council homes from their remaining stock”. Tenants in housing association homes could then purchase these homes under the “Right to Buy” policy. Profits from this will go towards a one-for-one replacement of affordable housing through the Brownfield Regeneration Fund, which aims to build 200,000 new homes on brownfield land in 20 of London’s new housing zones.

Londoners spend half their income on rent, which is not a surprise.For both Mayoral front-runners in the May 2016 election, Labour's Sadiq Khan and the Conservative nominee Zac Goldsmith, the elections are seen as being a referendum on London's housing crisis, and both are not accepting the Housing and Planning bill as-is. Khan wants to introduce a “London Living Rent” for new affordable housing – a rent cap of sorts – saying that rents should be around one-third of renters' income, allowing renters to save to buy. Goldsmith has proposed and amendment to the bill, that would make it mandatory to build two new “affordable homes” for every home sold in London.

Add to this mix prior “infrastructure tsar,” Labour peer Lord Adonis, who has suggested demolishing council estates to make way for “city villages,” with more homes built at higher densities, and you have a very interesting political situation.

I visited the NLA this past November for a panel discussion entitled, “New Ideas for Housing: Tools for Accelerating Delivery,” to see what the think tank had to say.

There are more people living in poverty in the private rented sector than in social housingWho are we building for?

Rick Blakeway, Deputy Mayor for Housing, Land and Property at the GLA, started proceedings by explaining that there is a mass exodus of 30-somethings in London that needs to be stemmed. As Blakeway put it, "Londoners spend half their income on rent, which is not a surprise." What is a surprise is how poverty has started to emerge in the private rental sector. "There are more people living in poverty in the private rented sector than in social housing," said Blakeway, "two million Londoners overall."

Blakeway targets one London borough in particular as a shining example of what can be achieved. "The most astonishing statistic is Tower Hamlets; a third of all stock has been built in the last decade in this one borough, this proves that a large volume of homes can be delivered."

Blakeway offers up the middle-ground, saying that London must "Focus around mid-market, not just deficit and supply within the mid-market. 80% of supply is only available to 20% of people." Blakeway concluded with the thought that "there is a significant amount of land to build on, but we still have a focus on big schemes whereas we need to look at the smaller scale as well."

Where are we building?

David Lunts, Executive Director of Housing and Land at the GLA, again brought up Tower Hamlets, saying building has increased by 29% in last ten years but focuses on suburban renewal and intensification within the suburbs, begging the question: "What is the potential for suburban retrofitting? Lunts looks to the Crossrail 1 construction as significant for housing growth, suggesting that building will probably continue to increase eastwards towards Barking and Dagenham. Lunts also looks to Greenwich and Newham to emulate Tower Hamlets. To the west of London, Old Oak in Acton will see 15,000 to 30,000 new homes all based around rail infrastructure.We are a determined, resilient and creative sector, but London has competition; people in their 30s are leaving.

The Changing Role of the Provider

David Montague, Chief Executive of L&Q (a housing association and residential developer) looked at the “Changing role of the provider,” and issued a stark warning that "This crisis is becoming an emergency. We are a determined, resilient and creative sector, but London has competition; people in their 30s are leaving."

Stating his position, Montague said, "our concern is less affordable rent and shared ownership; we would like to see investment in shared stock. The truth is that for social housing, people won't be able to afford to buy it, there is a vast number of people for whom it's not an option to buy." On their part, to combat this issue, Montague says that L&Q are looking at three options: cross tenure, looking more creatively at the assets they own to collaborate more with local authorities, and lastly, looking much closely at their operating costs.

Barriers to Accelerating Delivery

Christine Whitehead, Emeritus Professor of Hosing Economics at the London School of Economics, was candid when it came to dealing with the topic of barriers. Whitehead wearily, and with deadpan delivery, explained, "The subjects we're talking about now are not that different from 40 years ago, but affordability has got worse. If we are trying to stick to build rates, a third of boroughs would have to emulate Tower Hamlets right now. We've done so badly in last 15 years, that even with all current and future projects are taken into account, we're due to suffer until 2037."

Whitehead then pointed out the myth that the main barrier to sufficient housing is having enough land with planning permission – there are, in fact, large numbers of outstanding planning permissions out there, so the story is not straight forward. Whitehead looks to the size of sites and the fact that larger sites were delivering much less than they could – managed output rates are there to keep profits up.

Whitehead reserved special instruction for what she perceives as acute issues in the structure of construction industry. With its tired and outdated working practices and self-serving agenda, Whitehead asks the industry, "Is this really about land ownership and developers versus the rest of us?"

In the longer term, Whitehead looked to the emphasis on brownfield sites, suggesting that we should look outside of the inner circle of London, ending with the truism, "When we build infrastructure, do we not then effectively enable more effective use of surrounding land?"

New Approaches

Chris Brown, Chief Executive of Igloo, talks through his concept of new approaches to the crisis. Brown sees three challenges: demand, money and speed. We build large sites too slowly. "It could be like buying a car," says the enthusiastic Brown, "get a mortgage, a select plot, choose a home manufacturer, choose a home model and customise, then move in."

Brown cites a statistic that 75% of people don't want to buy from volume house builders and suggests the answer could be in a variety of small site stock, despite admitting that infill sites are contentious and, essentially "building in peoples' back yards". Brown suggests giving a community housing projects may work and that "developers aren't always the answer". Indeed, in the discussion that follows the seminar, Brown offers up the opinion "We are not a nation of NIMBY's – it's just that our builders build shit homes," to a mixed reaction from the floor.

We are not a nation of NIMBY's – it's just that our builders build shit homesModular Developments

Ivan Habour, Senior Partner at Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, brought a much-needed success story to the table with the project, “Modular housing using MMC”. Currently in use in Merton, South London, the project was from a brief to rehouse YMCA residents intp 36 units and a community office that could be re-deployable on temporary sites, and rent for 65% of market rate.

The solution was factory-built timber units using a volumetric system to ensure a construction cost determined by the process, not the absolute measurement. The 36 units took the place of two conventional houses, and delivery and assembly were manufactured 90% off-site, cost £35,000 per unit, and designed to last 60 years. And, as Ivan Habour noted, "despite its radical feel, everyone likes it."

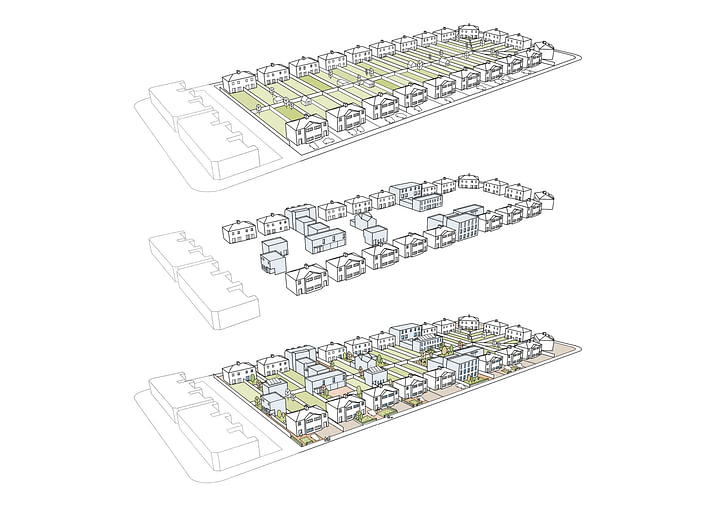

The word radical could be reserved for Riette Oosthuizen, Partner in charge of Urban Planning at HTA Design LLP, and Andrew Beharrell, Senior Partner at Pollard Thomas Edwards, with their “Densifying the suburbs” proposal. The shears were out as Oosthuizen asked us to "Suspend disbelief, let's look at the beloved English garden, there is a disproportionate amount of gardens in some suburbs." Paradise lost? "We are not talking conservation sites," explained Thomas Edwards, "we are looking at interwar housing stock, London outer suburbs could bring 1.4 million houses." The plan is to create local development orders between members of a suburban community, to then create pre-approved plot passports and take these plots up in neighbourhood plans over time.

Thoughts on Materials

The “Working with Timber” proposal by Sadie Morgan, Co-Founding Director at dRMM Architects, came with the simple message that, "Wood is good, simple, speedy and sustainable," and that we should be investigating timber for bespoke mass production. People should be happy where they live. Our role is to create a variety of living spaces for the 21st century.Morgan, a vocal protagonist for the benefits of timber in construction, notes that Trafalgar Place, a new development in Elephant and Castle in South London, was built using the material at its core.

The Role of the Architect

And finally, a rallying cry from Simon Child, Director of Child Graddon Lewis Architects and Designers. Child stated that the problem is that the housing crisis is London is largely hidden, or transferred to other towns and cities. The problem is a financial one and a political one, but, "People should be happy where they live. Our role is to create a variety of living spaces for the 21st century. Yes, stereotypes exist; landowners, developers, local authorities, communities – but we must essentially all provide a home where people want to be."

Planning for the Future

Talking to Peter Murray, Chairman of New London Architecture, after the seminar brought further guidance. "What's problematic for London is the fact that it has a negotiated planning system rather than a more formal one, and the pressures are so great now we do need to try and think in a more serious way about the shape of city we want. Let's look at “Vancouverism,” the very high-density centre of Vancouver with carefully designed, very well thought-out buildings. We don't have any guidance along those sort of levels, and I think we need to look at [it a] little bit harder. I think that's what the next Mayor needs to do – what is this place going to be like, feel like and look like."

Let's look at “Vancouverism,”... We can learn a lot from New YorkI offered the title of “art-director” as one that could be created for an architectural curator to London. Murray thinks for a moment and then responds, "I think that's a very good word to use actually," before continuing his mindful international recap. "We can learn a lot from New York," he continued, "it has many of the same problems as we do. The city has very high land values in the centre, emerging areas immediately outside the centre like Brooklyn, they also have problems delivering affordable homes, and they also have this crippling impact of international finance which is pushing up land prices."

Housing over Assets

One winner of the New London Architecture competition, WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff, already has direct experience of working to solve the housing crisis in New York, on a project that mirrors their entry into the NLA competition – Frank Gehry’s Beekman Tower, completed in 2011 (WSP served as the structural engineers).

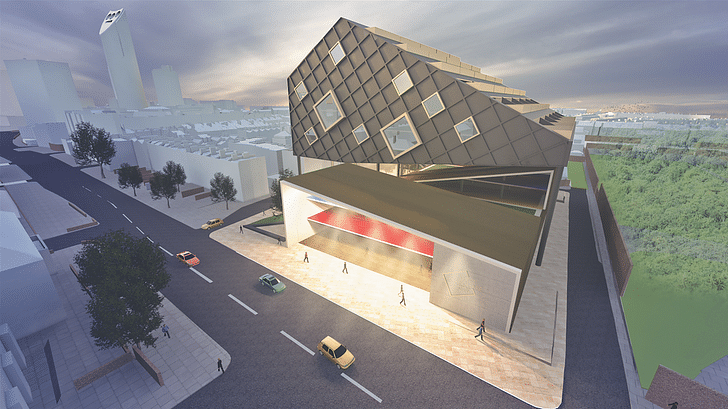

I visited Bill Price Head of UK Client Management at WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff to discuss the winning project, entitled “Housing Over Assets”. The project moots the idea that there is room for 630,000 new homes in London by resorting to building apartments above public buildings, such as hospitals, schools and libraries. Price agrees that this figure is not entirely accurate, as it doesn't take into consideration such factors as heritage sites – but even if 10% of public assets were to be utilised, the project would make an impact.

I started by asking Price why he thinks this project was one of the winners. "I think the idea won because it actually reinforces the idea of a city being dense – we're re-using land," explained Price "I think it refreshes social infrastructure, where many schemes don't. The project doesn't sell off the family silver and the things that you and I own. It's much more than a building solution. I think just getting architects to create buildings is not the answer, the sort of problem we have to deal with is the politics and the cultural shift going on, which is completely out of the engineer and the architect's hands."

I asked if the Housing over Assets project a reaction to land value. "In reality, there isn't a lack of space – there is a lack of the ability to obtain the space. We have this situation in London where the price of property is escalating. And of course, most money is generated from private residential, and that's probably not the kind of housing that London needs," explained Price. He then echoed a sentiment from earlier, "There is a bit of me that feels that any amount of engineering architectural building solutions is something we can always generate. In reality, there isn't a lack of space – there is a lack of the ability to obtain the space.It's not about me designing a building, its about politics, land and mechanisms for dealing with the process of house building, and the affordability of it really – and even, maybe, the expectation: how one occupies a property."

Where did the concept for Housing Over Assets come from? "This housing idea was rooted in the fact that most of our social infrastructure is in pretty poor condition," explained Price. "Schools, police stations, court buildings and doctors’ surgeries are frequently not fit for purpose anymore. The root of the idea is 'let's keep the notion of functionality on the site in the same place. We all need that school, but let's provide a new school, exploit the air rights with some residential.'"

“Exploiting the air rights over schools” may send many running for their placards and soapboxes. Critic Rowan Moore in the Guardian called the project a “downright ghastly suggestion for putting Shenzhen-style blocks on top of fire stations and schools.”

What does Price make of the potential public reaction to the scheme? "I know that we have the technical capability to build 'a bridge' over existing primary schools and put in residential, but that's not really what this is about. It's about flattening, removing tired infrastructure and refreshing it, and bringing it up to date."

The people thinking about this include the Greater London Authority. Price mentioned that Strategic Planning Manager of the GLA, Colin Wilson, “came to have a look.” Price also hints at a new project, “somewhere in North London, near a tube station,” where a former office block is being redeveloped with an NHS centre on the ground level, and housing above.

“I remember at the beginning of the process I said, ‘Why don't we consider putting that medical care facility in the bottom of the office building. The lesser residential value of the bottom would function very well as consulting rooms,'” said Price, then, with a twinkle in his eye, "and I think that's what is actually going to happen."

Robert studied fine art and then worked in children's television as a sound designer before running an art gallery and having a lot of fun. After deciding that writing was the overruling influence he worked as a copywriter in viral advertising and worked behind the scenes for branding and design ...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.