When Mexico City’s Central de Abastos opened in 1981, on land annexed by the government from subsistence farmers, it replaced the Mercado Merced as the central wholesale market for the city, but also served to consolidate 80% of the national food distribution in a single hub. Not many tourists visit Central de Abastos, and unless you work in the food industry, you would be unsure how to direct someone to get there (which didn't dissuade people I asked from making it up). Although de Abastos operates somewhat "behind the scenes", it is a fascinating case study because, while less urban and less public, it is the most critical link in the public market system that remains the backbone of Mexico City's food system.

Central de Abastos from pedestrian bridge. All photos and diagrams by the author, unless otherwise noted.

Central de Abastos from pedestrian bridge. All photos and diagrams by the author, unless otherwise noted.

Although urban development has since engulfed de Abastos, the center of supplies, it's location was initially chosen outside the city for reasons reminiscent of urban 'slum clearing': security, efficiency, and sanitation. The history of food systems being pushed out of cities is well chronicled in works such as William Cronon’s Nature’s Metropolis and Carolyn Steel’s Hungry City, which describe political and economic conditions precipitating modernist urban planning decisions. Cronon’s critical history of Chicago’s meat-packing industry provides a narrative structure for understanding Micheal Hough’s more recent argument in his book, Cities and Natural Processes - “the urban environment has been shaped by technology whose goals are strictly economic rather than social or environmental. This has contributed to an alienation of city and country and a misuse of urban and rural resources.”

Central de Abastos location map

Like other infrastructural facilities (for example, water treatment plants, power plants, or telecommunications structures), food markets, especially wholesale markets, are perceived as the unappealing underbelly of cities, and often located in ‘marginalized’ neighborhoods where residents can’t afford to buy political efficacy. The location of food markets, like other infrastructure, therefore walks the perilous line between accessible and invisible, characteristics with drastically different meanings depending on modes of transportation. With perhaps more potential than other infrastructures, as I’ve mentioned before, food markets also have the capacity to stimulate cultural exchange, social activity, and local economic development.

A happy couple at work

Carolyn Steel argues, “Wherever food markets survive, they bring a quality of urban life that is all too rare in the West: a sense of belonging, engagement, character. They connect us to an ancient sort of public life. People have always come to markets in order to socialize as well as to buy food, and the need for such spaces in which to mingle is as great now as it has ever been – arguably ever, since so few opportunities exist in modern life.”p.111 While Steel makes a point to temper this hint of nostalgia later in her book, I am always a bit suspicious of desires to ‘turn back the clock’. My aim is not to fetishize ‘traditions’, but to understand cultural relationships between architecture, urbanism and food systems in order to propose new opportunities with potentially broad social and spatial implications. Although Mexico City’s markets may seem timeless, the physical system is constantly adapting relative to a myriad of political and economic conditions.

One might expect that the relocation of the Mexico City food hub would have been disastrous for the vacated Mercado Merced (as it was for Les Halles in Paris or the Abasto in Buenos Aires, which have been converted into high profile malls), but the massive urban market continues to be a significant cultural and economic center (for food as well as prostitutes) since transitioning to a retail market. The site of Mercado Merced has been a major trading center since the city was known as Teotihuacan (before Cortes), the existing structure built to replace and expand Mexico City’s first market hall, originally built in the 1860s. Merced was connected directly to the metro system in 1969, and continues to be the largest and most famous public market in Mexico City.

Les Halles shopping mall, Paris. Credit: www.spa.archinform.net

In the 30+ years that it has operated, urban development in Mexico City has since engulfed the once remote site of the Central de Abastos, although it remains disconnected from the metro system, and relatively difficult to access directly. Virtually everyone I spoke with recommended a different route to get there. I retraced my path on the metro several times before finding the most agreed upon “correct” stop, and waiting with a group of people on the side of the highway until a bus stopped and everyone filed on. I knew I was in the right place when I realized the smell of raw meat was effusing from the man sitting next to me.

Despite difficult access from the metro, CA does have it’s own bus terminal, which connects it to various public markets throughout the city! From the bus terminal you walk on a pedestrian bridge over an 8-lane highway, sidestepping pushcarts and vendors with blankets on the floor until being directed into the expansive network of halls and loading docks that comprise the market, which, according to the Mexican government website, it is a whopping 327 hectares. That’s almost as big as Central Park in NYC, which weighs in at 340 hectares.

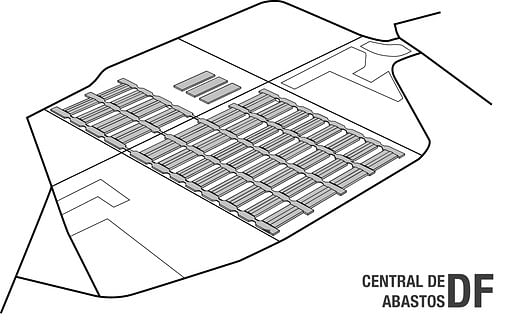

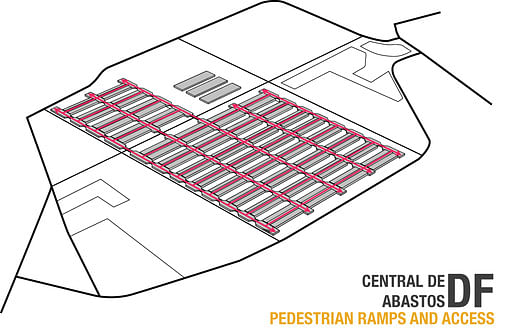

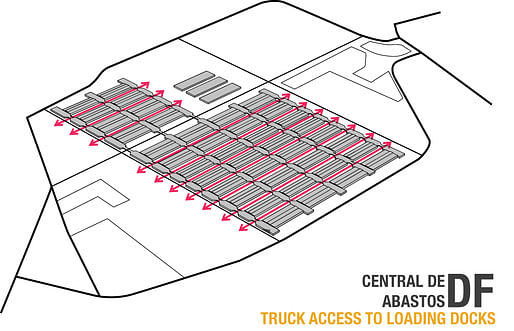

Unlike the Central de Abastos in Oaxaca, which sprawls under informal additions from its central structure, the Mexico City CA is organized, clean, and efficient, reminiscent more of a massive modern airport than what you might expect of a Mexican food hub. Architect Abraham Zabludovsky’s brilliantly simple circulation strategy had me initially confused, until I realized that the slight ramps connecting parallel halls actually formed bridges allowing delivery trucks to pass under, creating an interwoven system that effectively resolved the potential conflict of pedestrian and vehicular movement.

Inside the Oaxaca Central de Abastos.

According to a USDA Foreign Services GAIN report, published in November, 2011, “The largest segment within the CA is the fruits and legumes sector comprised of 900+ warehouses housed within 8 industrial sites. These have individual names and are given an alpha-numerical listing for easy address identification within the market (i.e. “El Parian” Nave K-L through Z).”

That’s right. They’re not just “halls”, they’re “Naves”, as if this was the Cathedral of Food markets, which perhaps is a more appropriate title.

Inside Central de Abastos, a typical retail "nave"

Inside Central de Abastos, a typical retail "nave"

These Naves, with exceptionally calibrated daylight systems and expansive ceilings, connected on the ground to loading docks through rows of warehouses, with digestion systems that served to accept shipments on the dock end and distribute food to waiting customers in the Nave. Some of the Naves had exquisite food displays and were full of retail customers, while others were more focused on wholesale customers, such as the Nave of Onions.

Inside Central de Abastos, the wholesale "Nave of Onions"

I find the combination of a wholesale/retail market is particularly fascinating, because it describes a type of hybrid system that potentially creates active cultural public spaces while simultaneously operating as an efficient machine. It’s the art and science of architecture made tangible through an economic system with real spatial implications.

The Mexico City CA is not connected to an urban pedestrian network that would allow people to walk here from a home or office, but it is functioning more an more as a public retail market as private corporations like Wal-Mart increasingly prefer to build their own distribution facilities. Nicola Twilley described the process in a fascinating post on her Edible Geography blog:

“If the construction of La Central tells us a fascinating story about the evolution of governmental attempts to control food in order to tame cities, the market’s declining market share, down to handling between twenty and thirty percent of the nation’s food supply from eighty percent when it was first built, is testament to radical shifts in scale within the food business…According to USA Today, a 2008 government report concluded that La Central was gradually shifting toward small wholesale or retail customers, “meaning it is basically just becoming a big public market.”

The “shifts in scale” she describes are the result of trends toward industrial production and distribution systems in Mexico since NAFTA, which allow corporations to control more the food system, and consolidate more of the profits.

Despite it’s enormous scale, the CA was designed to support hundreds of thousands of small independent producers and consumers, not a few large ones. According to Twilley, “La Central was built to be the giant hub that tied together smallish farmers and merchants with smallish tianguis and restauranteurs. Food flowed through a single site that connected producers to vendors in a process that theoretically created greater efficiency and more competitive prices.”

The loading docks. View from a pedestrian ramp connecting two 'naves'

According to the aforementioned USDA report, the market still accommodates 59,000 vehicles and 300,000 visitors every single day, 365 days of the year, which is more than all of New York City’s airports combined. Those visitors distribute food to Mexico City’s 318 publics markets, and countless food stands, tianguis, restaurants, and private kitchens. “It generates more than 10 billion dollars annually and supplies the daily needs of 25 million people. As one of 60 central markets located nationwide, Mexico City’s Central Wholesale Market (CA) is the backbone to the traditional market segment in Mexico.”

Pushing a cart up the ramp between naves inside Central de Abastos.

Although many people view public markets as ‘traditional’, Central de Abastos is a strikingly contemporary work of public infrastructure that has accommodated radical economic shifts, and will undoubtedly continue to evolve. As trade liberalization continues to privilege private corporations, which levy control over industrial production, the CA will be an increasingly important hub for small-scale, independent commerce, a physical connection between growers and consumers, especially those that can't afford the industrial alternative.

I am a graduate M.Arch/MLA student at UC Berkeley, and grateful recipient of the 2011-2012 John K. Branner Fellowship, an annual traveling fellowship awarded by the UC Berkeley Department of Architecture. I will spend the 2012 calendar year visiting public food markets in major cities on 5 continents to research the relationship between markets and the infrastructure of food systems, focusing on the cultural and urban design implications of local economies. This blog will follow my journey...

No Comments

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.