Oaxaca

I am a little over a week into my Mexican adventure, the first leg of my fellowship (explained in the initial post if you’re just joining) although my experiences here will take a bit longer to distill into a comprehensive report. I am writing from the city of Oaxaca de Juarez, 6 hours (by bus) south of Mexico City, where I initially intended to spend just a few days, but it turned out to be irresistible. It’s my first detour of the trip, and I expect not the last.

Images from the Tlocolula Sunday market, south of Oaxaca de Juarez

Images from the Tlocolula Sunday market, south of Oaxaca de Juarez

Oaxaca is a city of about 250,000 residents, concentrated in a dense colonial urban fabric, with public food markets creating nodes of social and economic activity in every neighborhood. Even more astounding than the bustling Oaxaca city markets, however, are the tianguis, the traditional pre-hispanic market festivals that occur once a week in the predominantly indigenous towns throughout the Oaxacan valley. The system works much like farmers markets in the United States, except that theses massive weekly markets do not pop up in parking lots, but explode out of the central market building (every town has a mercado), and take over the streets, plazas and alleyways around the mercado. The mercados are of Spanish origin, and were constructed during colonial settlement, so the weekly tianguis are an interesting cultural hybrid of Zapotec, Mixtec and Spanish traditions. The mercados operate daily, so the weekly market (a different day in each town) is an expansion of an existing system, rather than market from scratch. Unlike farmer’s markets in the US, the vendors are usually not farmers themselves (unless they are selling whatever is left over from the weekly harvest in their back yard), but resellers of goods procured that morning from the Central de Abastos in Oaxaca. I’ll expand on all of this later, but the Central de Abastos is basically a wholesale/retail market that creates a hub for food and other goods for the urban region. The food comes in from all over Mexico, but is not necessarily “local”, or even “organic” the way some people in the United States might expect. I was on a crowded bus out to the Ocotlán market, west of Oaxaca, last Thursday, when I started thinking about what “farm to table” means in different contexts.

The Local Market

Currently, local food in most US cities is seen as a luxury. This is undeniable when considering the target populations to which farmers markets and specialty grocers market themselves. The fact that you have to pay more for food grown closer and distributed more directly may seem paradoxical, but can be explained primarily by the relatively boutique scale of the sales volume, and the exclusive “publics” that are catered to. Don’t be offended foodies, I’m not excluding myself from this description …

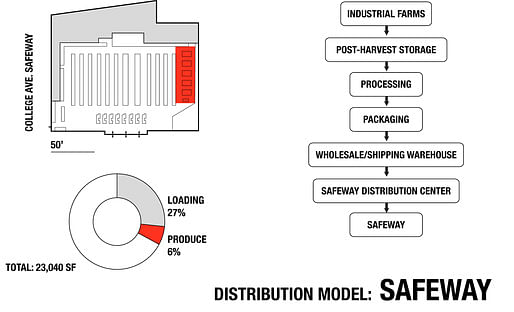

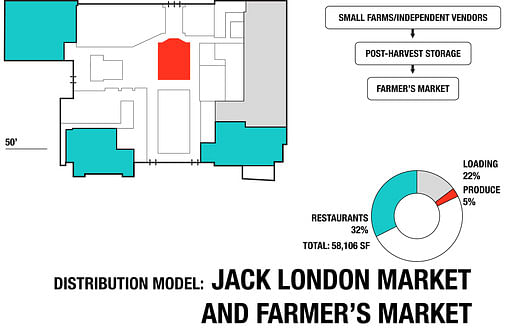

But you have to admit, there is a direct connection between market typologies and methods of production in the United States, although it is not as clear-cut in Mexico. The connection is basically this: industrial production, which predominantly occurs far from urban areas, corresponds to industrial processing, manufacturing, and distribution systems, all the way down the long line, and finally, to your industrial supermarket (which sends its profits to wherever its global headquarters might be.) Conversely, food produced closer to, or within, urban areas is more likely to come from smaller farms and ranches, be less processed, and find its way to urban consumers more directly (although in much lower volumes than industrial models with current distribution systems).

75% of California Farms are less than 100 acres. Small Farms are closer to Urban Areas and more likely to Sell Directly to Consumers.

The Market effects the Distribution system, and vice versa

According to Michael Pollan, author of The Omnivore’s Dilemma “There are good reasons to think a genuinely local agriculture will tend to be a more sustainable agriculture [in the way sustainable is defined as a holistic and systemic understanding of ecology and urbanism]. For one thing, it is much less likely to rely on monoculture, the original sin from which almost every other problem of our food system flows. A farmer dependent on a local market will, perforce, need to grow a wide variety of things rather than specialize in the one or two plants or animals that the national market (organic or otherwise) would ask from him”.(1) For those of you skeptical of the efficiency of small farms, consider the work of UC Berkeley Environmental Sciences Professor Miguel Altieri. In 2009, Altieri published a study in the Monthly Review that debunked the myth; “Although the conventional wisdom is that small family farms are backward and unproductive, research shows that small farms are much more productive than large farms if total output is considered rather than yield from a single crop.”(2)

This is not to suggest that small family farms should necessarily replace industrial models (nor could they), or that innovative technology couldn’t be integrated in smaller operations to make them more efficient. Like Pollan, I am attracted to the potential resilience of a food system that offers real options for diverse demographics. “We may need a great many different alternative food chains, organic and local, biodynamic and slow, and others yet undreamed of. … The great virtue of a diversified food economy, like a diverse pasture or farm, is its ability to withstand any shock.”(3)

So what would it take to support an “alternative” local food system? Obviously, there are more issues than I can possibly address here, but for local food to become more affordable and available to a wider public than its current market, at least two factors would need to be fulfilled: 1) more locally produced food would need to be available in urban areas, and 2) the value of locally produced food would need to be competitive with that of industrial models. These two factors are intrinsically linked. Most distribution models, for example, are prohibitively expensive because small-to-medium size growers (again, those closer to urban areas) operate economically as artisans. The pinch is not on a limit of productivity, however, but an inability to efficiently distribute food to urban consumers. So what is preventing these independent growers and ranchers (who often operate on land at constant risk of underperforming economically relative to development options) from reaching a broader base of consumers? One of my basic arguments is that limitations in existing distribution infrastructure represent a massive opportunity to expand the local food market in the United States.

The architectural and infrastructural opportunities of such an expansion would require a diverse set of strategies that would operate on varying levels of formality (many of which, like food truck networks, farmers markets, and CSAs are already happening). From fresh food trucks to regional food hubs, these components of a local food system could operate at various scales and with corresponding requirements for political and economic support. 3tk’s comments on my first post articulated this issue with thoughtful criticism. “Are markets the necessary proto-type?...What is a more post-modern multi-narrative solution that is adaptive (tactical interventions), it may be semantics, but the way the statement [my original post] is written it seems more that you are looking for a uniform, top-down, single solution answer. IF you are implying this is a more democratic food distribution system it necessitates an alternate systematic approach.” It’s a valid critique of a potential shortcoming, but as I stated in my first post, “Public markets may be just one component of an active local food system, operating at a scale between wholesale markets (that sell exclusively in bulk) and farmers markets (that are almost always boutique).” I’m not implying that large, fixed public markets are a one-size-fits-all answer to food distribution systems in every city, but could be one way to enhance the more informal operations that have already catalyzed local economies, public spaces, and food systems.

I also recognize the immense overhead capital that a public market structure would require, and I don’t deny that there would be significant political and economic (top-down) interests involved. (I’m not an expert on this, but from what I’ve read it seems a bit screwed that government subsidies in the US often work against the independent farmers who need it most…to promote the overproduction of corn for hyper-processed shit we don’t need.) One of my objectives for this year of research is to understand the way public markets, as urban components of food systems evolve, grow, and behave informally within their organizational and political structure. The established markets we now see in major urban centers often grew out of informal markets that occurred in the same location, and which significantly influenced urban growth patterns around them. Peter Smiths’ 2009 article in GOOD magazine, title “The Public Market Renaissance”, briefly investigated the initial failure of Portland’s Public Market, which was open from 1999 to 2006, and reported annual losses of about $1 million, before down-sizing and reopening. Since true public markets operate as a flexible framework for independent, local businesses, they must be responsive to political, social and economic fluctuations, which can be potentially erratic. Rather than trying to impose a new, finished physical market on city, I expect that a structure would most successfully facilitate its intended activities if it was designed to be adaptable, responsive, and to grow with the intangible market that it (more or less) contained.

The appeal of “local”

Much like “green” and “organic”, the word “local” is increasingly being co-opted by corporations intent on making a niche market out of it. It is widely known in the food industry, thanks to reports from private consulting companies like the Hartmann Group, that “local” as a label is appealing to consumers, and corporations are trying to use it as a selling point. This is another reason why food marketed as “local” tends to be more expensive, because desirable qualities in any product increase demand and therefore price, regardless of how much it may cost to produce and distribute. Unfortunately for the nation’s top grocers, “local” may be more difficult to appropriate than “organic” was 15-20 years ago. Corporations like Whole Foods participated in the industrialization of organic production, with a little help from the USDA, to make the “organic sector” a $26.7 billion industry by 2010, up from just $1 billion in 1990. Safeway’s 2009 CSR report (Corporate Social Responsibility) claimed that “roughly 30% of produce sold by Safeway annually is local”. I spoke with representatives from Safeway’s consumer relations department in November 2011, but they refused to disclose the name or location of any of their “local partners”. Safeway apparently hasn’t realized that the word “local” doesn’t mean anything without context (no matter what you’re talking about). But the USDA doesn’t yet regulate use of the word the way they do “organic”, so for better or worse, you might have to ask a few questions for yourself…

At the very least, public markets are worth studying as alternatives to industrial food systems, which may be necessary, but more or less so for different cities and different urban contexts. Markets are forever fascinating for the clues they transmit about culture, another factor that is more or less local depending on where you go. The Bay Area (not just SF) is a globalized metropolitan region, but is also unlike anywhere else in the world. Why should the Bay Area rely on the same generic corporate grocers as everywhere else, especially when more than enough of most food items are produced within its 9 counties?

While not every city has the local bounty of the Bay Area, many are already looking for alternative options to supermarkets. Through a global comparative analysis of markets as a link between cities and food systems, I hope to uncover a little about what makes each place that I visit different, rather than just how they’re the same. The questions that I’m asking are not intended to consolidate knowledge in a plan for “How to build a public market anywhere”, but to selectively compare how markets operate in various places worldwide. My methods, like my itinerary, will evolve as I go, but I will attempt to combine my writing with various levels of spatial and tectonic analyses, interviews, audio, video and photography, economic metrics (like a cost of living analysis), climatic factors, demographics, operational intricacies, other intangibles, etc; anything and everything that will communicate the architectural, infrastructural, social and economic situation of each place.

Next up, more on Oaxaca…thanks for reading.

Friends in Mexico City, I'll be there by mid-February. Hope to see you then!

Citations:

(1) Pollan, Michael. The Omnivore’s Dilemma. Penguin, 2007. p.258

(2) Altieri, Miguel. Monthly Review Magazine. V.61, Issue 3, 2009

(3) Pollan, 261

I am a graduate M.Arch/MLA student at UC Berkeley, and grateful recipient of the 2011-2012 John K. Branner Fellowship, an annual traveling fellowship awarded by the UC Berkeley Department of Architecture. I will spend the 2012 calendar year visiting public food markets in major cities on 5 continents to research the relationship between markets and the infrastructure of food systems, focusing on the cultural and urban design implications of local economies. This blog will follow my journey...

3 Comments

Chris,

It would be a shame if during your travels you did not hope over to Cuba to visit Havana and Cienfuegos. I just came back from a trip studying similar topics, spent some time working with some farms, doing research on markets, etc.. They have a very interesting system in place, with much of their "local and organic" processes (possibly ironically) created out of pure necessity to survive after the collapse of the soviet union and from our embargo. The infrastructure of food can really be felt as you walk through Havana, stumbling upon urban farm after urban farm, and markets in all shapes and sizes. If you're concerned about the travel restriction, these days all you would really need is a letter from Berkeley saying that you're doing graduate research and Obama will let you go.

If you want to know more or have any questions shoot me an email!

Danny

Hi Danny,

Thanks for your comment. I saw a documentary about Cuba's food system recently, which suggested that Cuba could be a model for other societies depending on how economic systems react to peak oil. The documentary is called "The Power of Community: How Cuba Survived Peak Oil". It paints a rather uplifting picture, but I would be interested to know more about the struggles and limitations of the system as well. I was planning to go to Cuba from Mexico City later this month, but that was before I knew I would be spending three weeks in the state of Oaxaca. I'll be back in Mexico City over the summer, so hopefully I can take a trip to Havana then. Is your Cuban research documented on your blog anywhere? I looked through a few posts, but didn't find anything about it. I would love to know more!

Saw that documentary. That, and everything published about the topic paints a very uplifting picture.. but let's not forget why it's actually there, essentially out of pure necessity and need to survive. There are plenty of struggles and limitations.

I haven't touched my blog in a long time.. shame shame, I know.. but I uploaded some pictures on flickr. (http://www.flickr.com/photos/dannywills/sets/72157629076009385/) There is a lot of tourist stuff to sort through, but a good collection form the organoponicos and markets. If you want some research material, let me know!

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.