MAPT, a Danish architecture practice several months shy of its fifth birthday, leaves an intricate trail of breadcrumbs behind its projects. It's not easy retracing the steps between a realized MAPT idea and its inception. The firm's works are often products of an ongoing "mad science," after all— years of lab experiments, workshops, lectures, installations, tests, and trial runs.

by Katya Tylevich

I call Anders Lendager in Copenhagen to talk about the big ambitions and humble beginnings behind MAPT, which he and partner Mads Møller founded in 2005. But for a minute, we digress to talk about Los Angeles, where Lendager and Møller studied and worked prior to launching their firm. Laughing a bit, Lendager calculates the percentage of MAPT's methodology that he attributes to US influence. Here and there, Lendager talks about MAPT in the language of formulas and equations, wherein unexpected and unusual variables line up behind an "equals" sign. MAPT is a practice with a detailed and multifaceted "About Us," in other words. Unraveled, the acronym spells: Mediating Architecture Process and Technology. Throughout our conversation, Lendager acts as something of an architectural GPS system, backtracking through the various detours and interesting side paths that lead to MAPT worksites, navigating through his firm's objectives, and pointing out something called a "non-datascape" along the way.

Katya Tylevich: You're juggling many works-in-progress now, between your labs and experimentations. Are your simultaneous endeavors actually extensions of one another, incarnations, or different entities entirely?

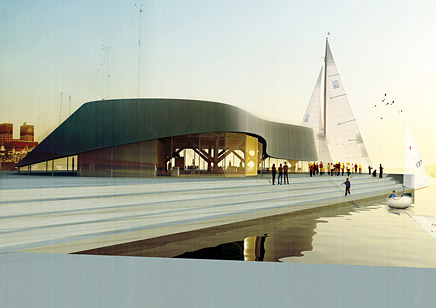

Anders Lendager: Now that we've been MAPT for four-and-a-half years, it's clear that many of our experiments — in workshops, and with different schools —materialize into large-scale projects two or three years down the road. It's nice to see how it makes sense to collaborate. There's a project we're working on now in Oslo [Bølgen], for example. In the past, we'd done a lot of workshops looking at the potential of various surfaces. Now, finally, we have a project in which we get to program a single curved surface on a large scale.

KT: Bølgen is a very interesting shape. With good reason, no doubt?

AL: Well, historically, the Vikings used to put their boats up and turn them over in the winter —to use as shelter for living quarters. Our design is a way of doing that again. We're creating a cultural area for jazz music, good dinners, good times, and we're using a "boat shape" as climate control. What you get, actually, is one big radiator with gypsum on the whole of the outer skin. By having such a big area as your radiator, you can use very low temperatures to heat the space. It saves a lot of energy. We also use the shape of the building to accelerate the winds coming in from the fjords; this creates natural ventilation. Bølgen will be the first LEED certified project in Norway. For us, that is very important. Different layers of ideas come into play here, and it's really nice to have a client who wants to make these ideas happen.

↑ Click image to enlarge

Bølgen: Aker Brygge, Oslo, Norway, 2009

↑ Click image to enlarge

Bølgen: Aker Brygge, Oslo, Norway, 2009

KT: Taking into consideration that you're a young firm, is it difficult to find clients like this — who jump onboard with your ideas?

AL: Before, we didn't want to compromise at all, but we realize now that in architecture you have to think in terms of a very long timeline to reach your goals. You need to crawl before you run your hundred meters under 10 seconds. Our main goal is to build. That's what we want. We don't just throw projects away form the start because a client is "too difficult." In a few years, we'll have more and more projects in line with the way we see things. But we need to get something in the ground to be taken seriously. So we try to get something — at least one thing — that's really interesting and new for us into each project. This way of thinking is behind many new works for us.

KT: So even one realized idea, between many compromises — that's a success story.

AL: You just have to take on different projects: The ones where you go through 100 percent with your ideas— like the project in Oslo— and the ones where you see just how much you can do. We have a project in Herlev, just outside Copenhagen. It's a super cool project, we really like it, but it is a compromise. We didn't have free hand to do whatever we wanted. In my opinion, that's what you do if you want to get started. That, or stay stubborn for 20 years. Or have really rich parents. It's been seen before that that works well. [Laughs.] But that's not at all where Mads and I are coming from. So we're trying to be humble and build up as much as we can.

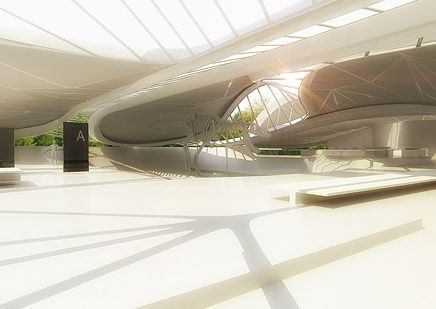

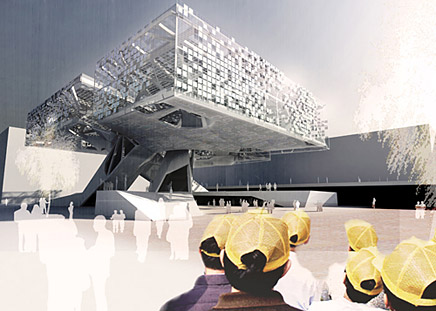

↑ Click image to enlarge

Herlev Shopping Crown, Herlev, Denmark, 2009

KT: The first time we talked, you made reference to Denmark's "pragmatic architectural landscape." What is a pragmatic architectural landscape?

AL: I'm talking about these "non-datascapes," where all the data has been left out or simplified. It's a very public architecture in the sense that it doesn't have an academic level. Everyone understands what it's about and that's why it's very popular. But it's also easy to copy. So, the profile in most Danish architecture firms "under 40" is almost the same. It's obvious these firms are influenced by the same things; they use the same tools, they have the same ways of manifesting architecture. That's where I think we stick out. First of all, we're influenced by American architects — we studied at SCI-Arc and worked in New York. We also try to maintain a more complex approach. That is, we believe information is still important. The handling of new technologies in architecture — digital tools, manufacturing tools — is something that influences our architecture. To have one foot in the more academic world and another in "lab work" is really important to us. It creates a different kind of Scandinavian architecture, in my opinion. And that's what we hope to do.

KT: What does a complex and academic approach mean for the aesthetics of your projects?

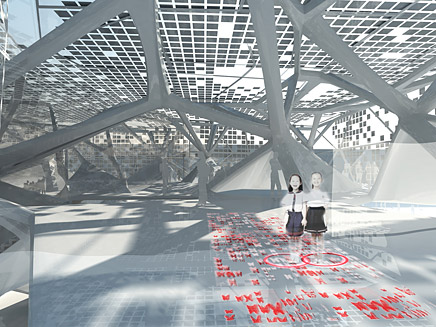

AL: Building processes certainly influence our aesthetics. One of the things we're investigating is the language of sustainable architecture. Right now, a lot of sustainable architecture built is influenced or designed by engineers, and very few architects are in a position to design with sustainability as a tool. When we cross that line and gain more knowledge about sustainability and the different aspects of the building process, I think that starts to manifest in the architecture itself. It starts to create new forms, new surfaces, new ways of thinking about space. Imagine you can interact with a wall to get information about the building you're in. It's a new way of thinking about architecture: Not as a dead surface, but as something active, something you touch and interact with. There are so many new things I find interesting, now — even insulation!

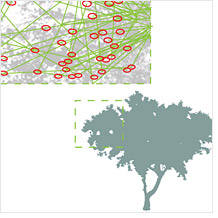

↑ Click image to enlarge

Eco Botanica, in collaboration with GRITT

↑ Click image to enlarge

Eco Botanica, in collaboration with GRITT

↑ Click image to enlarge

Eco Botanica, in collaboration with GRITT

KT: Is it important for you that your clients share your enthusiasm for insulation, for example?

AL: One of the great things happening now, with all this talk about "sustainability," is that — all of a sudden — the client wants "sustainability" badly. And when the client wants something badly, that opens up a whole new potential for us as architects. We can design something that has meaning and solves problems. It's a different way of communicating ideas, which we find really fantastic.

KT: Communication is basically your middle name. Can you explain your role as "Mediators"?

AL: Over time, we've found that the mediation of architecture means knowing a bit about law, a bit about politics, and so on. So our mediation is integrated with different areas and professions. A good example is our COP 15 Pavilion: a very sustainable Pavilion which shows the transformation of Nordhavn — a shipping area — into 3 million square meters of housing and schools and living areas. We actually show this transformation using shipping containers. Everything is made of sustainable materials, it has all the insulation you need to make an energy-plus-house; it has LED light fixtures, it has recycled window material, which creates this fantastic translucence. This building shows transition. And the interesting thing about our approach is that we communicated with the manufacturers of sustainable materials. We had this kind of mediation between "economy" and "idea." We brought participants into the project who could benefit from its success. So mediation is actually what made the project possible.

↑ Click image to enlarge

COP 15 Pavilion, Nordhavn, Denmark

↑ Click image to enlarge

COP 15 Pavilion, Nordhavn, Denmark

KT: COP 15 — the conference and the Pavilion — is about a global mediation, in many ways. This seems to resonate with MAPT's profile and ambitions.

AL: We don't believe in local fascination. We don't believe in just having Copenhagen as our playground. We like the idea of an "open source," as opposed to "holding your information tight." It's about reaching out and also having people from different countries "reaching in" — we get influenced both ways. That's a way to develop our architecture. We would love to build in Los Angeles, for example. Whenever you go to a different city or country, it develops you.

↑ Click image to enlarge

Prague National Library, Prague, Czech Republic, 2006

KT: How formative was your time in Los Angeles and at SCI-Arc, specifically?

AL: I miss Los Angeles so much. I thought that would never happen, but I really, really miss it. I had a tremendous time at SCI-Arc, and worked on some fantastic projects. It was exactly what I needed: an institution that pushed the academic approach that far. It was something I was missing in Denmark. American schools really push the academic approach, and I only have one criticism of this kind of school: It creates hundreds of superstar architects and only 1 in a million actually makes it. Guys I studied with are either not in architecture anymore, or are working in the most boring offices you can ever imagine, though their theses were amazing. There's no market, or people don't know what to do with their knowledge, or how to start a business. It's only the really, really hardcore types that start a workshop where they can follow their dreams.

↑ Click image to enlarge

Danish Pavilion, Expo 2010, Shanghai, China, 2008

↑ Click image to enlarge

Danish Pavilion, Expo 2010, Shanghai, China, 2008

Danish Pavilion, Expo 2010, Shanghai, China, 2008

KT: Well, your Model For MAPT Architecture is certainly hardcore.

Model For MAPT Architecture

AL: We want to use architecture to make things better. We want to integrate technology and sustainability into the new language of architecture. And we don't want to make it any more complex than that. There's always that question about technology and society: what influences what? Our idea is to keep technology and society as equals. This creates a new kind of architecture, with an emphasis on the way society moves. The new ways a society moves creates a new kind of technology. With a new technology, a new kind of society emerges, and with it, the need for a new kind of architecture.

↑ Click image tiles to enlarge

Approach towards the Danish Expo Pavilion design

↑ Click image to enlarge

Danish Expo Pavilion - Section

KT: That's an enormous idea, of course. Is being a young practice an advantage or a disadvantage in trying to tackle it?

AL: I think things get difficult when we "don't know better." Sometimes we run into a wall with something we think will be easy, but it just isn't. On the other hand, we push through when other older businesses say, "Oh, forget it!" So there are upsides and downsides. It is difficult, though. When you're a young office, you still hold on to your ideology, especially if you started just out of school. Then, all you have to build on is your ideology and your hopes. If you start out in a bigger office — more commercial — then your ideology will probably be crushed into the ground after a few years. [Laughs.] Then you have to find it all over again, if you start your own practice.

↑ Click image to enlarge

Ceiling installation

↑ Click image to enlarge

Ceiling installation

KT: What's changed for MAPT since 2005?

AL: The drastic change is that we are now 13 people. We're starting to have an "economy" now, and we're professionalizing. We still have our crazy ideas and hopes, but now it seems easier to actually go through with them. We have a strategy for how we want to do things and how we approach clients, which is comforting. It's not rocket science for us anymore.

Katya Tylevich is a contributing editor for Mark Magazine. She writes for many different publications.

Creative Commons License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License .

/Creative Commons License

6 Comments

I have done a superficial glossing over of this article, and love it. Great images interesting ideas: complexity offered with simplicity. Thanks for the introduction to this firm. Nice work.

Indeed...Quite inspiring and brilliant to hear the actuality come through!

Nice work!

A poignant statement by Lendager on certain American architecture schools...

American schools really push the academic approach, and I only have one criticism of this kind of school: It creates hundreds of superstar architects and only 1 in a million actually makes it. Guys I studied with are either not in architecture anymore, or are working in the most boring offices you can ever imagine, though their theses were amazing. There's no market, or people don't know what to do with their knowledge, or how to start a business. It's only the really, really hardcore types that start a workshop where they can follow their dreams.

I'd like to know more about the key differences of the European system compared to the American approach. Any comments?

I agree. It's nice to hear young principals talking about their experience in school and their impressions of the profession. It's also nice to hear the affinity for the academic experience in US architectural schools.

Beautiful but some of their words don't match their projects.

where's the sustainability when it appears that most of their buildings require more glazing and more structure than normal?

just because you put overhangs on your windows won't erase the fact that they're 3 stories tall.

it's not just MAPT, but i'm getting really tired of this truly empty "sustainability"

These guys know what's up.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.