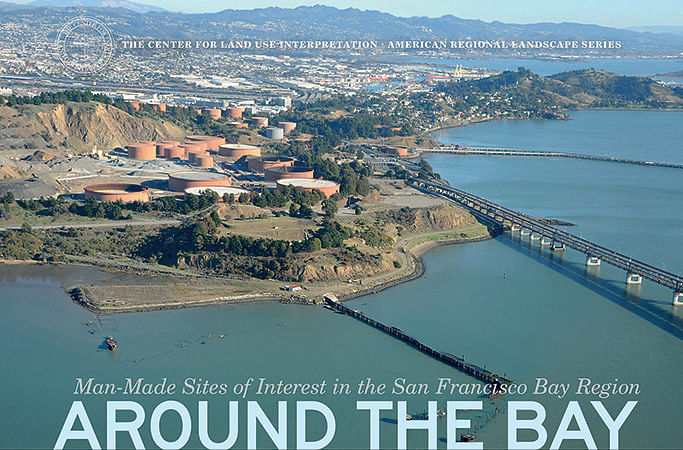

Around the Bay: Man-Made Sites of Interest in the San Francisco Bay Region, a new photobook from the Center for Land Use Interpretation, catalogues portraits of the Bay Area's complex and historied landscapes.

“Around the Bay” pairs portraits of bayfront nodes with a brief historical profile, focusing on areas that blur the exchange between military and civilian, artificial and natural, industrial and residential, somewhere and nowhere. Around the Bay is the second book from the CLUI’s American Regional Landscape series, following Up River: Man-Made Sites of Interest on the Hudson from Battery to Troy. The CLUI operates as an exhibition and education space headquartered in Culver City, California, and presents particular styles of human intervention upon the Earth’s landscape -- featuring topics as diverse as refrigerated transportation networks, nuclear testing sites, and most recently, the internet’s physical infrastructure. In an apolitical yet provocative way, the CLUI aims to sharpen the individual’s ability to effectively and critically read any landscape, as a legible impression of human influence.

There's something mildly intoxicating about the images in Around the Bay -- a photo-series of landscape portraits from the greater SF Bay Area. Photographed from the heady height of a helicopter on a clear day, the landscapes highlight the diversity of function along the waterfront. Authored by Matthew Coolidge, also the CLUI's founder, Around the Bay pairs these portraits with a brief historical profile, focusing on areas that blur the exchange between military and civilian, artificial and natural, industrial and residential, somewhere and nowhere.

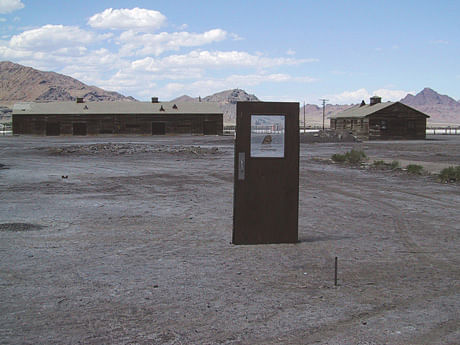

I sat down with Matthew Coolidge to discuss the release of Around the Bay earlier this September, although it was hard to stay on track -- Coolidge was busy installing the CLUI’s next exhibition, “Networked Nation: The Landscape of the Internet in America” earlier that morning, and our conversation quickly branched off into issues of nature preservation, regional identity and the invisible hand of satellite photography. Coolidge has been an associate professor of curatorial practice at California College of the Arts in San Francisco, and while headquartered in Culver City, the CLUI aims to eventually expand its educational influence across the entire U.S. through the ambitious American Land Museum. The goal is to divide the nation into “Interpretive Units”, based generously on topographical regions, each of which will house a museum devoted to dynamic exhibitions of the surrounding landscape. While the CLUI already has outposts in Wendover, Utah and Lebanon, Kansas, the American Land Museum could be a new form to represent national identity, determined by landscape histories as opposed to strictly political or social ones.

The following is an excerpted transcript of our conversation.

Amelia Taylor-Hochberg: Around the Bay is the second book in the CLUI's Regional Landscape series. How has the focus of the series shifted in its second iteration?

Matthew Coolidge: We didn't know when we did the first one what the second one would be. We thought about different things, discussed it with the publisher, decided on this because it seemed like a good match to the other one too -- kind of a second chapter looking at the West Coast. San Francisco is, in some strange ways, analogous to the Hudson, being the shoreline of New York City is a sort of front and back-space -- the U.S. looking towards Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries. Looking at the landscape of the nation as created through the window of the Hudson River School and the first national identity represented by an art movement, San Francisco is also a portal, only to the Pacific. It's the front door to the pacific, historically. Los Angeles is a bigger city and has a bigger port than San Francisco today, but 100 years ago, 50 years ago, before World War II, San Francisco was the dominant portal for America in its relationship to the Pacific empire. Like New York, and coming from the Atlantic and Europe, here San Francisco is the analogue looking westward at the Pacific. And its interior spaces of networks within the Bay, from the shipping industries going throughout with the same relationships as the Hudson -- the power plants, the pipelines, the industrials spaces the quarries -- the things that make the city front-door possible are, behind that door in the backspaces, the various layers of the Bay.

ATH: I think there's a really interesting relationship between the present-day Bay Area identity and its military and industrial heritage. Especially in regards to what the CLUI is working on now, the digital infrastructure, and how it bumps its head against the natural landscape that is still there.

MC: It's not that nature doesn't exist anymore -- nature exists in something which is in concert with human activity. You can't have natural landscapes in a weird way, every landscape is a natural landscape. We're interacting with our environments like all animals, only we're doing it on a great scale with a greater complexity. But we're essentially modifying our habitat like other creatures. In the old sense of what nature was, that doesn't exist anymore, because there isn't a molecule on the surface of the Earth that hasn't been affected by a human agent of some kind. Whether it's through climatological, meteorological disturbances and changes -- really in terms of just physically moving material around on the ground -- everywhere, pretty much, has been affected by humans. The places that we haven't "touched" have been affected by weather and climate modifications, but also they become kind of preserved in a sense, by being artificially constructed. A National Park is not a natural place; it's very natural-esque, but in terms of the old sense of what nature is, it is as much a construct as a parking lot outside of Wal-Mart.

It's not that nature doesn't exist anymore -- nature exists in something which is in concert with human activity. ATH: I heard you taught a class at California College of the Arts in San Francisco on the concept of "nowhere". Could you talk about that; is that even a possible concept anymore? And how that relates to your interpretation of the "land" as a performative act -- that merely talking about something is interpreting it?

MC: The class was based on the idea that there is no nowhere. We used that kind of terminology for the first part, but it morphed into another kind of class, that perhaps I would have called "somewhere", if we had to call it something. But it was all so that this idea of "nowhere" doesn't exist; there is no "away", you can go away but then you're there. This notion of "someplace else" is just sort of obsolete, in the same way that the old idea of nature is obsolete. Everything's been discovered and visited and inhabited and interacted with and is connected to everything else, in a sense of an ecology; interconnected in the broadest sense of the term is also something we think about.

But the class was meant to introduce, to challenge, that idea. Certainly there are the facts and reality situations, then there are our impressions and our beliefs, and those things are often in interesting contrast. I wanted to work with the students in examining a place that wasn't in their consciousness; that was considered somewhere that they wouldn't normally go. It was a curatorial practice program in the graduate department. We would go somewhere in southern Louisiana or wherever and experience the sense of being from somewhere else; of going there and trying to make sense of it and establish a place there, an interpretation of it. Each year the class created an impression and an interpretation, in the form of some exhibit or public program, related to the place we visited. And with a very conscious awareness of their view of it, as a type of interpretative mechanism between the viewer and the observer of the object. It was this idea of the subjectivity creating a sense of a place. That is a very subjective and interpretive thing. And in general, objective awareness is something that we're awfully conscious of with everything we do -- the view creates the object, and the medium that presents it modifies it. It's impossible to really see objectively.

Nature exists not as physical material anymore, but as a process -- as the systems that cause interactions between things. ATH: At some point, will we reach a type of human-landscape singularity? Where the humans are interpreting the landscape as a human substance that is being manipulated as part of the landscape, so they keep going back and forth, saying "where is the originating cause here? Who is making us who we are?" Or whether we are just acting as animals, using fancier tools to accomplish the same thing.

MC: I think one of the effects of understanding the landscapes we create and interpret, as a manufactured impression of a place, is that the way we see the world is as important as what we do to it. In that the construction of a view is also an awareness of an intent, and a value system, to govern actions and interactions. I think just understanding the landscape we built as a kind of script that we wrote and are learning to read, and learning that we can change it, a modifiable script, is really what the CLUI is all about, ultimately. The birds and the other biota that interact with the way we interact with the world are parts of that, but in a way also exist separate from it. They are the things that are beyond our intent and are victims of what we do, or materials affected by our systems. But that is the latent systems of nature. One could imagine maybe that nature exists not as physical material anymore, but as a process -- as the systems that cause interactions between things. Those are the laws of nature, the physics that preexisted and that we learned to harness to some degree. But those are the actual intractable natural structures of dynamics and material, and energy. But the material artifacts within that are part of the human path exclusively.

ATH: I'm trying to imagine the internet infrastructure's own cycle and rhythm -- its recycled quality, in the way that there are natural cycles of elements to contribute to the ecosystem that it perpetuates -- that there's another analogous cycle in information, in how the internet perpetuates certain information around the world and how that motivates human though. Could there be a new type of nature based on that for humans? Not contradictory to the one that already exists, but perhaps there's an analogy there to deal with both types of nature.

MC: Robert Smithson had this dialectic between site and non-site, and it seems in the information age there's perhaps now a tri-alectic: site, non-site, and website -- internet space. In the site/non-site idea, you had the location (the site), and the representative location (the non-site): either photograph or map, the non-site references to this place that is somewhere else. In Smithson's case, the gallery, the photograph of the pile of dirt, the stuff that he would collect from the site -- that was the non-site. But in a tri-alectic from information space, you have this physical location that you can point at (that exists in space), you have the representation of it through books (physical material that samples, is directly related to it), then you have the hypertext -- interconnected, web-mapped, reference-library access, everybody's flickr photos or whatever of the place -- the non-dimensional representative space of that site. As a third entity, it's something Smithson couldn't have anticipated, but it's a fun exploration to think of this "new space", this information space as a new realm, that is like the physical location and like a representative interpretive version of it, but it is a kind of holistic and "omniscient" version. Resolution between physical space, representational space and webspace has always been in our DNA as an institution. "Omniscient" in quotes because all it does is connect all those things together, including the locating of the site exactly through internet mapping systems.

So we've always sort of thought about the representative space and the web version of space floating above it, in a way. With everything we do, we think about those three things, and reconcile those three things as an institution that started up with the world wide web in 1994, when people were doing Netscape. So we emerged with the web and then the CLUI database (which was carried online fairly early on) was all about an internet space representation of actual place. Resolution between physical space, representational space and webspace has always been in our DNA as an institution. Going back and forth between the two, challenging one side and the other, this information-space show that we're putting together now looks at that issue dead on. Where are these actual places in the non-placeness of the lab, the information space? We're kind of calling the cards in a way, saying "the virtual world doesn't exist without the physical world". There really needs to be an awareness of that. There needs to be a consideration of the physical qualities of our information space. Until we're just floating amoebic energy forces in space, we need to recognize the fact that we live on this finite planet. I don't know that information itself is infinite either -- what happens when we create the Borges complete version of our world? How big will that server be? Will that essentially be a version of the world, and all its physical forms, represented digitally?

ATH: It's like the distinction between countable and uncountable infinities. There's this concept that the internet is infinite, yet all contained within the countable infinity of objects limited to Earth, and that can cause some cognitive dissonance -- how can what I conceive of as infinite be contained, at all? Having that core of reference for existence being in the infinite realm and not the physical; in the non-site instead of the real site -- that could be extremely disconcerting to a lot of people.

MC: Sometimes we refer to the Bay as this hole in the middle of the city. I guess it is kind of like that -- it's a barrier dividing Fremont from SF. It's this sort of barrier that you have to get on these bridges full of traffic to transcend. But it is a community and it defines itself by its term, The Bay Area, where the margins of that lies is debatable, but in general it extends throughout the different systems of the Bay until you get to someplace with a stronger regional identity -- upriver or at Antioch maybe, where it becomes The Delta. Arguably, the Bay Area stops where the Delta begins, at least in that direction. That's sort of the limit of that area, but most people in San Francisco wouldn't think of their friends in Pittsburgh as being part of the same system, yet they are and that strand of the shoreline is the connective tissue that kind of keeps the whole Bay Area together, but also paradoxically it also divides everybody. It's a thing you look at, you can embrace, you gaze across the water in Albany or Richmond, but ultimately it's about this proximity being controlled by this void -- it's a deadspace in terms of its inhabitation.

That's the way most museums should be; a museum of a place. ATH: To me, the Bay Area is most defined by that east-west binary, to have the freeway that starts on the other side of the country end on the SF peninsula, and passing through the East Bay and over the Bay Bridge to get there.

MC: The Golden Gate bridge is more about California than the nation. It's about San Francisco's relationship to its coastal environment, not about its relationship to this great east-west thing. Interstate-80, that's America's main street, connects New York City directly to the Bay Area. Of all the interstates, it's the one connecting two of the biggest population points. Roughly it follows the migration west, but also the railroads, and the first telephone line was connected along 1-80. All these east-west links went along the I-80 corridors more than in any other place. That I-80 ending at the Bay Bridge is the San Francisco connected to a national fabric, and the Golden Gate is more of a north-south thing. They were built at the same time, but the Bay Bridge has always been kind of the ugly duckling even thought it's the work horse. There's a great film done in the '80s called "The Other Bridge" all about the Bay Bridge. It's a real celebration of infrastructure.

ATH: Would you consider releasing any of the photography duties to robots or drone technology? Is it a conscious choice to always ground the images with people behind them?

MC: All the imagery we use in our exhibits, generally, is taken by people within the organization because it represents a kind of ground-truth. It's a primary layer of secondary media, generated by us. But we don't use images from official sources and other representatives, so it's not like a photographic clearing house or service agency. These are images that are from us, so at least there's only one media layer. But, unless we're doing an exhibit about different perspectives or different ways of representing, we'll make that very clear. If we do an aerial land scan, it's important for us to be involved directly with that rather than just hire someone directly to do it. But we do increasingly take advantage of opportunities to use other ways of seeing, so long as it's contextualized and clear. For example, this exhibit about cyberspace, the spaces of information -- most of the content is actually from the web, from other sources. We use Google Street View to take pictures of the internet exchange points around the country: major data centers of New York City and San Francisco and Silicon Valley, and Atlanta, Chicago -- all those images in one chapter are from Street View and we thought that would be a good way to see these things. It's an internet self-portrait in a way, and we have another chapter in there that's all about earth-stations of satellite control facilities, satellite information. A lot of people get their internet out of cable these days. It has an artifice that's been programmed by humans to create something like what we'd see if we just had our eyeballs look at it. That info goes mostly through the sky through satellite systems, so these ground systems for communication from cable companies and other information companies still use satellites too. Those facilities we look at through Google Earth, through a vertical view straight down. One of the chapters is all images: vertical views of satellite earth stations from the sky, appropriately.

We are using the robotic view I suppose, in a sense, that at times when it's appropriate, and making it very clear that that's the medium we're using, and sort of justify its use within the thematic structure of the exhibit. But ultimately, the final chapter in this exhibit is images of data centers, the "new" data centers as we call them, the ones that were built as dedicated structures for housing data centers. Those photos were all taken by members of the organizations, ground-truthing these places. We play with that idea of the robotic view quite a bit, and we have done entire exhibits on printed photographs from Google Earth. It is a new form of landscape photography. It has an element of ground-truthing in that it is kind of automatic, but still represented through a medium that has some identity. Which runs from the aerial -- aerial photography has been embedded into satellite layers. The closest view for a lot on Google and other online maps is aerial photography too. So somebody is taking a picture and manipulating it. Stuff from space of course is all just bandwidth of energy that then is assigned color priorities. It's hardly photographic in that it's capturing reflected light -- it's capturing reflective waves that have been assigned colors. It's a mechanistically-formed kind of photography. It has an artifice that's been programmed by humans to create something like what we'd see if we just had our eyeballs look at it.

ATH: Do you think the presence at Oakland Museum of California will change the impression people get of CLUI?

MC: For each project we do, in terms of building an exhibit, it's trying to do another twist on how things are presented in exhibition spaces of various kinds -- ours being a hybrid space, or a space that's particularly branded to this organization. It's not an art museum, it's not a science museum, it's not a visitor's center, it's none of those things, but it's got parts of all those things. We like that neutrality, but working with OMCA, of all the museums in California, that's a great one because it's a museum about California. So if you're doing a project about California, yes, it's kind of an art museum? But it's not, it's a history museum, cultural museum… it has a wonderfully open identity. I can't think of any other museum in California that has that kind of openness. It's a regional museum, it's a local museum, it's a history museum, it collects artifacts, but for the entire state of California, which is more complex and crazy than any other state, really. It's a great thing to have: a museum of California. They've been really great to work with. That's the way most museums should be; a museum of a place.

ATH: Is there any place that you'd like to focus on for the next book from the American Regional Landscapes Series?

MC: I guess now that east coast and west coast have been done, there's either the Great Lakes or the Gulf of Mexico. So I don't know yet, where the next one will be, and whether it will also focus on a waterway. Waterways are interesting because we build our places next to water. They're the front-spaces of our communities and our land-uses are clustered around waterway systems. It also provides a linear narrative point, where you can string things together geographically very nicely. So it's probably a method that we'll use to do the next book, too.

Former Managing Editor and Podcast Co-Producer for Archinect. I write, go to the movies, walk around and listen to the radio. My interests revolve around cognitive urban theory, psycholinguistics and food.Currently freelancing. Be in touch through longhyphen@gmail.com

3 Comments

SALT Online just came up with this. "Modern Essays 5: Graft" BOOK OF DAMS.

Sort of reverse of the article.

Around the Bay poeticizes waterfronts, as an in-between mediating space, whereas "Book of Dams" seems to go straight for the neck. I wonder how SALT would react to something like this: "Floating island community off Silicon Valley draws interest from hundreds of tech startups".

That would be really severe I suppose.;.)

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.