This op-ed was initially conceived as a series of critical Twitter messages by Fred Scharmen, aka sevensixfive, directed at blogs (including Archinect) that have been providing ongoing exposure of new architecture projects in China, considering China's unfair capture and treatment of artist/activist Ai Weiwei. In an effort to investigate this issue further, and hopefully spark a little productive debate, we invited Fred to pen this op-ed.

Should the media protest the treatment of Ai Weiwei by ceasing promotion of all new architectural work in China? Should architects refuse to take on new work in China? Should we continue to support the work of architects and artists in China, but only with a disclaimer? Please share your thoughts in the comments.

At the time of this writing, the artist Ai Weiwei has been detained without charge by Chinese authorities for 53 days. Given the history of Ai Weiwei's unique relationship to architecture, and the ways in which our discipline, and Weiwei himself, intersect with the Chinese state, the ongoing uncritical promotion of design work within China by international media outlets feels naive at best, and destructive at worst.

Weiwei has famously compared the Bird's Nest Olympic Stadium in Beijing, for which he is credited as co-designer, to a "pretend smile", worn by the Chinese state, along with the rest of the pageantry surrounding the 2008 summer games, to distract the world from internal issues like human rights, corruption, and pollution. This false smile persists.

Ai Weiwei is no stranger to the political uses of architecture. In addition to the Bird's Nest stadium and other projects, in 2007 he designed and built his own studio complex in Caochangdi Village, a suburb of Beijing that has since become a thriving arts district. The same year, he co-organized, along with Herzog & deMeuron, the Ordos 100 project, an even larger arts district in Inner Mongolia. This area is rich in the coal used to fuel China's economic expansion, and has one of the fastest growing GDPs on the planet. The project is based around one hundred 10,000 square foot villas, each designed by a seperate architect, hand selected by Ai and H&dM. In the center of the vast neighborhood plan is a copy of Weiwei's Beiing studio complex. Only phase one has begun construction, and the city of Ordos is currently one of China's famous 'Ghost Cities' the empty shell of an overspeculated and underpopulated real estate bubble, or strategically banked housing stock for China's rapidly urbanizing population, depending on who you ask.

Weiwei was invited by officials in Shanghai to design and build yet another version of his studio complex in that city, as a catalyst for even more arts based development. In early 2011, his permit was revoked, and the central government destroyed the building while it was still under construction. It's widely believed that the destruction of his Shanghai studio was intended as warning and retaliation for other ongoing projects that had begun to occupy a continuum between art, architecture, and political activism.

After the devestating Sichuan eathquake in 2008, Weiwei began collecting names of students killed when their school buildings, many constructed without regard to safety inspection and regulations, collapsed. This was a situation that had been downplayed and hidden by local and national governments in China. He began continuosly posting these names in many online venues, as part of his wide ranging internet presence. When police harrassment began to intensify, he further fed the cycle by documenting the harrassment itself. In 2009, he was beaten so badly with sticks by the police, that he required emergency brain surgery on a stopover in Munich.

In pre-olympic China, optimism abounded among western architects about the prospects for openness and democracy within their new client state, and there was much speculation, particularly among prominent academic practitioners, about the role that their projects could play in the transformation. Weiwei's collaborator on the Bird's Nest, Jaques Herzog, told Der Speigel in 2008, just before the games:

"We too cannot accept the disregard for human rights in any form whatsoever. However, we do believe that some things have opened up in this country. We see progress. And we should continue from that point. We do not wish to overemphasize our role, but the stadium is perhaps a component of this path, or at least a small stone."

The diffuse, porous space of the stadium's perimeter would be difficult for authorities to monitor, new forms would engender new social relations:

"... our vision was to create a public space, a space for the public, where social life is possible, where something can happen, something that can, quite deliberately, be subversive or -- at least -- not easy to control or keep track of ... We see the stadium as a type of Trojan horse."

And as early as 2004, Rem Koolhaas was writing, in WIRED Magazine, about the potentially transformative effect of the looping form in OMA's newly designed CCTV Building:

"But in China, money does not yet have the last word. CCTV is envisioned as shared conceptual space in which all parts are housed permanently, aware of one another’s presence – a collective. Communication increases; paranoia decreases."

From the perspective we now occupy, in mid - 2011, we can point out, in no uncertain terms, the falseness of these claims, and the failure of these hopes. Things have not opened up in China. The stadium was not a component, or even a stone, on the path to any openness. It was not a Trojan Horse. Sharing conceptual space has not resulted in a decrease in paranoia.

And in China, as elsewhere, money does have the last word. In early 2011, in a publication entitled "Building Rome in a Day", the Economist noted: "At current rates of construction, China can build a city the size of Rome in only two weeks." Despite concerns (despite the Ghost Cities, and the existence of 100,000 unsold apartments in Beijing), the Economist assures its readers that the Chinese real estate boom is not a bubble about to burst. According to the Economist, there is still money to be made. Real estate prices in Shanghai increased by 150% from 2003 to 2010. In 2011, housing investment as a component of Chinese GDP tripled.

Since the Beijing Olympics in 2008, coverage of iconic architecture in China has continued unabated. The hollowness that accompanied words about new form and social change from a previous wave of academic western practitioners has faded away. Instead of broad critique of those empty claims, the international architectural press has moved towards coverage of even more spectacular projects in China. Instead of opening up a dialogue about the possible role of architecture in social transformation, architects working in China have backed away from any expression of hope for increased openness and respect for basic human rights, but they haven't stopped working.

Even as, at the burst of the bubble, work elsewhere in the world has begun to again take more of a social and organizational turn, China is still a place where large shiny double curvature wins the day. The press has embraced China as a kind of last redoubt for parametric digital formalism and iconic shapeshifting, seemingly blind to the role that these cultural projects play as loss leaders for large development schemes. As the Economist notes, there is still money on the table when it comes to Chinese real estate, and there is still soft power to be capitlized on when it comes to the transmutation of cultural institutions into global prestige and legitimacy. The false smile gets wider, and toothier.

To trace Ai Weiwei's architectural trajectory is instructive. From his involvement with, and later disavowal of, the (iconic, mediated, overstructured) Bird's Nest stadium, to his turn towards the (hidden, censored, understructured) school buildings in Sichuan, there is the path of someone who has started to realize that his work in building was being used by the state, who then turned built work back against the state, using it to reflect the human cost of internal corruption.

This isn't to raise again the question of wether or not to work with "evil" clients, we are free to work for whoever we choose (or who chooses us). This is about recognizing the political and economic uses of architecture. To most institutions and governments, architecture is literally a tool. Weiwei's engagement with built work, and his artistic practice, with its focus on reproduction, authenticity, individuality, and the constant issue, in a large country like China, or any networked society, of people-as-pixels, became enmeshed in these issues. Given that he was beaten, nearly killed, and forcibly detained, while advocating for building code enforcement, you might say he's taken these questions to their furthest possible conclusion.

There are no easy answers. I personally believe that new form does have the potential to enable new social relationships. If we, as architects, didn't believe that built space could change lives, we wouldn't do what we do. The students whose bones were broken in Sichuan certainly had their lives changed by architecture. When I was in Ordos in 2008, to present the villa project I had worked on for Keller Easterling Architects, spending a week in that environment, with those people, and meeting Weiwei certainly had an effect on my life. It is not enough to merely say that CCTV is an office building for government censors, and the Bird's Nest is a giant political distraction, Rem and Herzog were wrong, and that all building in China is wrong. Just as it is equally unproductive to simply reproduce the press releases for the latest spectacular cultural institution to be completed or proposed in China , without caveat or disclaimer: this state jails artists. "Stunningly Omnipresent Masters Make Mincemeat of Memory". Architecture is large enough to be both radical social transformer and retrograde political instrument, if we're willing to talk about it. These things must be the beginning terms in a larger conversation about architecture in China, and in the world.

Original sources for above photos:

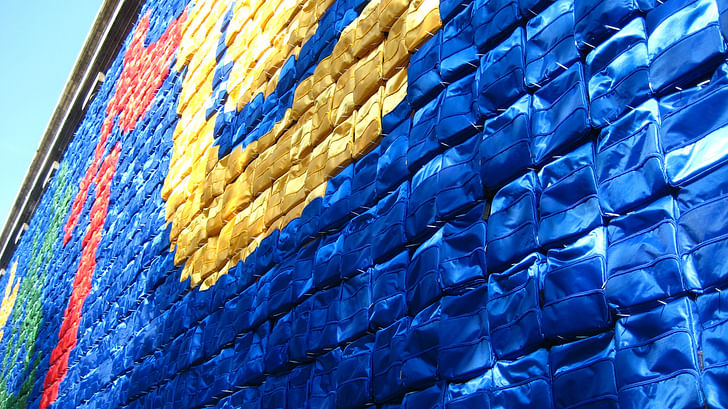

Weiwei's installation on the facade of Haus der Kunst in Munich. Photo: © monoculaire

Physical model of the Ordos project. Photo: © Fred Scharmen

Beijing National Aquatics Center (Beijing Water Cube). Photo: © Fred Scharmen

Sichuan Province after 2008 earthquake. China. Photo: © Wu Zhiyi / World Bank

Unlicensed Architect, Amateur Urbanist, Uncredited Designer, Sometime Researcher and Writer

8 Comments

Architecture is large enough to be both radical social transformer and retrograde political instrument, if we're willing to talk about it.

talking about the social impact of architecture is a luxury many of us cannot afford. we're at a point where there are 1000s of us clamoring over such little work that we're basically willing to do anything - even if it is ethically and morally contemptible. asking a starving person to think about all the other starving people is a bit disingenuous.

I'm not saying that this debate isn't important - it is extremely important - but those who have the most to tell also have the most to lose. I do worry that those who do the most social damage through our field lack the ability for critical reflection (too busy gettin' paid) - but there are many of us who at one point have questioned why we even need to build in the first place - and either quietly toil away for others because we cannot see any other alternative, or, if we're lucky, leave the field entirely.

There is a lot of fear in our profession - and it keeps most of us quiet.

'Toasteroven' describes the conundrum for many. Few will stand on principle when the roof over their head is in jeopardy. Few can afford too. That said, I firmly agree with with Fred, we can't get to where we vitally need to go as a species, unless we stand on principle and risk the burn line.

Toasteroven brings up another point debated by myself for years. Why should we build? Building 'green' is one reason, but I see a lot of so called 'Green' design that is anything but. So it has a 'Leed' certification, and used sustainable products(Shipped half way around the world), it still is too big, way too big in most cases. Green starts with a small foot print first, and minimal construction, and anything you can do to make it self sufficient is a bonus.

Thanks for the article Fred, and thanks to 'Archinect' for this conversation.

PS! Ai Weiwei is a universal hero, a true human.

"Just cause it looks human, doesn't mean it is" aikiv

I admire the author's sense of social awareness and advocacy of a worthy cause but, as a designer working and living in China, I find this Op-Ed to be extremely self-righteous and generally ignorant of the actual conditions here.

1. While the Chinese government is corrupt and despicable, how much better is the US? In the past decade alone the US has started an illegal and unjustified war that has lead to the death of thousands of people, detained prisoners indefinitely without bringing charges while also torturing them (for a refresher on the methods of torture: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2007/jan/03/guantanamo.usa) and obliterated over 200 years of constitutional law by (in a policy started under the Bush administration and continued under Obama, according to the 'New Yorker') keeping a copy of every email sent in the US and wiretapping citizens without warrants. I could go on and on and on. Maybe the author should stop working in the US if he believes that practicing in a certain country is equivalent to endorsing that government's policies. I don't support the detention of Ai Weiwei anymore than I'm guessing the author supports waterboarding. This is similar to the attitude most Americans have towards China regarding the environment: that the Chinese are destroying the planet when Americans actually use 4-5 times more carbon per capita than the Chinese.

2. The author drastically overestimates his understanding of the building industry in China. He falsely assumes that a singular building model exists in China: over-sized, iconic, unnecessary, insensitive and government-sponsored. Just as 99% of projects designed in the US are not the next Disney Concert Hall, 99% of projects designed in China are not the next CCTV. In my time in China (albeit only 1 year), I have not worked on any projects that would be considered iconic and personally know only one other designer here that has. Likewise, most projects are not government commissions. The author seems to be under the impression that all architects working in China have some sort of Albert Speer-type relationship with Hu Jintao. Most clients are developers, who are indeed more open to aggressive design than American ones. However, very few let architects run wild like GIC did with Thom Mayne. More time is spent figuring out circulation and parking codes than complex parametric facades, which do not, in fact, grace the exterior of every building here. (BTW, the author was involved with the design a Greg Lynn Blob Wall, the height of self-indulgent formalism.)

3. There's a unique opportunity to help China develop in a more sustainable way than most Western countries did. If populous developing countries like China and India begin to consume resources with the same voracity that America does, the results will be disastrous. Foreign and Chinese architects have a role to play in this process by promoting sustainable design to clients who are not currently aware of the movement. Vacating the premises to prove a moral point about the crummy government does a disservice to the general population. Additionally, most projects are spaces where people work, live or relax, not museums and Olympic stadiums. Consequently, architects have the ability to improve the day-to-day life of many, many people through thoughtful and intelligent design.

4. The author should consider more realistic ways of protesting Ai Weiwei's detention that are focused on the actual problem (which is the government and not architects). First, given the state of the world economy, architects and architecture firms are not going to stop doing business with China. Without foreign work (mostly in China), many firms wouldn't have survived the past few years and many more architects would be unemployed. I fail to see how decimating our own industry in an act of martyrdom would be helpful in amplifying our voice. Second, the Chinese government wouldn't care if we left anyway and the overall impact would be minimal. For every foreign architect there's a thousand Chinese ones who can do the job, a growing percentage of who are Western-educated and able to offer fresh perspectives.

5. Architects producing built work don't have the luxury of creating idealized architecture in a theoretical environment. Built projects are a series of compromises between clients, architects, tenants, citizens, engineers, politicians and lenders. Of course, the result isn't going to be perfect and some of the projects in China are terrible. But isn't that the case everywhere?

6. Architects are not real estate consultants and do not have the expertise or local knowledge (especially foreign architects) to determine whether a certain market within China is overbuilding. This is an issue for developers and policy makers. Building too much does create a bubble, but building too little pushes up prices. Its a fine line we are unlikely to ever master.

This passage from Sam Jacob's recent review of Steven Holl's newest museum in Nanjing (which is a part of a luxury villa/cultural development), from the April edition of Domus seems to tie in nicely with this Op-Ed. Jacob writes:

"First, CIPEA confirms architecture's status as a commodity, a thing that creates value. Here the value that architecture generates is recouped privately rather than for wider social benefit. Second, in the autonomous space that the resort creates, a certain idea of architecture flourishes. Within this exceptional space, the quid pro quo is this: in accepting the idea of architecture as a mechanism of creating private value (rather than public), architecture is at liberty to pursue its ever-present disciplinary dream of formally autonomous projects. A resort like this is an extreme example of the trade-off that characterises much contemporary architecture: by disconnecting from social and political concerns, architecture can fulfil its formal aspirations. Giving up claims to an all-encompassing idea of architecture strengthens its capacity in other areas. The deal is mutually beneficial: the more architecture does its thing, the more value it generates for its client."

So perhaps the question Fred, that architects need to ask themselves is whether or not they should/want to care or involve themselves with concerns such as those you highlighted here or whether they are interested in purely formal/disciplinary issues.....

As a non-architect I would like to think that architects (or any profession) can align their professional trajectories with the concerns of a world-citizen/human. However, as others have pointed out it is tough to do so when worrying about keeping a roof over your head. As honestly, I myself have been finding out lately...

It really does not matter in the larger scenario if firms refused to work in China. What WOULD matter, though, is if journals and websites stopped publishing chinese projects and glorifying them, in the same way Anish Kapoor et al are trying to convince international art dealers and galleries to not sell in China.

As someone who has worked on tons of projects in China, I can vouch that self-image (and aggrandizement) is a huge part of the Chinese clients' psyche, mostly to pander to their CPC comrades. Negative PR will have a much stronger effect on the Chinese government.

(As for posters here claiming to 'help the chinese' with their green agenda and effecting change, I would urge you to look deeper and accept the fact that most people are working in China, because there is simply no other option for most of us these days. There is not need to justify making a living, by claiming lofty principles)

Speaking of negative PR, we were working on a large project in Ordos, and the clients were literally shitting their pants when the NYT article on Ordos as a Ghost-City came out.

@hey now - thanks for reading, and for providing your perspective from inside China. In the article, I've tried to be very clear about my own background and relationship to this kind of work, and I've also tried to underscore that, in my view, there isn't one clear answer or policy here. This isn't about trying to convince anyone not to work in China, it's about trying to start a conversation about the usefulness of large, highly visible, heavily publicized, cultural and institutional work, and to think out loud about the role we all play in promoting it. If you missed that point, you didn't read very closely. There are a few other things that your comments bring up, that I want to address individually:

1. "While the Chinese government is corrupt and despicable, how much better is the US?"

The answer is simple: the United States doesn't have a clean report card when it comes to human rights, but we as a nation are doing much better than China. Nobody is here to excuse the War on Terror, or Guantanomo Bay, or the practice of extraordinary rendition. But there's a recognizable difference between a military action that detains suspected combatants from the battlefield, and the practice of removing an individual, an unarmed artist and a citizen, from an airport, and holding him without charges for two months now and counting. Ai is only the most recently prominent individual jailed for expressing dissent, for details on a much more extreme case, look up information on the disappeared lawyer and activist Gao Zhisheng. For some perspective, I suggest downloading the Human Rights Watch 2011 World Report, which goes into a lot of detail on the despicable practices of both the United States and China. There is no equivalence, China is worse - way worse.

2. "The author drastically overestimates his understanding of the building industry in China."

Again, it was never my intent to generalize about the state of all new construction in China. I am only trying to illustrate this specific connection between large cultural and institutional projects (like Ai Weiwei's studio(s)), arts based development practices that use these projects to drive the construction of more basic housing, and the global media machine that reproduces the new and shiny and weird and curvy (which, as you point out - nice googling! - I've been involved in myself, and still occasionally enjoy, no easy answers!).

3. "There's a unique opportunity to help China develop in a more sustainable way than most Western countries did."

On this point, I could not agree with you more. Sustainability is outside the scope of the current article, though.

4. "The author should consider more realistic ways of protesting Ai Weiwei's detention that are focused on the actual problem (which is the government and not architects)."

I bought the t-shirt, does that count? Seriously though, I'm an architect, artist, educator, and writer. I wanted to point out this particular relationship between art, architecture, and China, and do it with writing. And again, I'm not suggesting that architects en masse exit China, just that we think a little bit more about this bigger picture, and talk about it. I'm curious, though, what realistic ways of protesting the detention would you suggest?

5. "Architects producing built work don't have the luxury of creating idealized architecture in a theoretical environment. Built projects are a series of compromises between clients, architects, tenants, citizens, engineers, politicians and lenders. Of course, the result isn't going to be perfect and some of the projects in China are terrible. But isn't that the case everywhere?"

Again, couldn't agree more! This principle is actually the foundation of my own practice.

6. "Architects are not real estate consultants and do not have the expertise or local knowledge (especially foreign architects) to determine whether a certain market within China is overbuilding."

I'm not a real estate consultant, but arts-based development projects are something that I have a lot of experience with. I've worked on arts and culture projects in China, Singapore, Abu Dhabi, Las Vegas, and extensively in Baltimore. Look up the concept of the "loss leader": this is why shopping malls want Nordstroms, why cities want stadiums, and why nations want museums. They are willing to subsidize the construction of these flagship enterprises, taking a loss, so that future development of more basic stock will follow. At the larger scale, it is less essential that capital actually stop somewhere and land in a specific bank account, and more crucial that it keep moving: renderings, press releases and other promises of the shiny-to-come are the leader of that movement. Nations, in this respect, are little different from corporations, this is why they are obsessively focused on GDP, and sometimes very upset when the creators of their cultural capital are saying unpleasant things.

Fred - thanks for taking the time to compose your thoughts, and for inciting this discussion...however brief, it is easily one of most content rich discussions that v3.0 has seen to date. while i have a few things to possibly add, i'd rather see more from the thoughtful respondents above...and maybe will find an 'in' somewhere further down the page.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.