The one thing you will not find in school--or even on Architecture Registration Exams--is a course on how to get work, yet it is one of the most basic needs of any design practice. In fact, if you don't have an equal ability to experiment in getting work as you do in doing work you would be fortunate to make it past the first five years.

UpStarts is a series of features on the foundations of contemporary practice. It will have a global reach in which practices from Europe, North America, Asia, and beyond will be asked to address the work behind getting the work, and the effect of cultural contexts. The focus will be on how a practice is initiated and maintained. In many ways, the critical years of a fledgling design partnership is within the initial five years, after the haze and daze of getting it off the ground. UpStarts will survey the first years of practice as a tool for tracking the tactics of the rapidly evolving methods for sustaining a practice.

Archinect's chief editor John Jourden talks to Beijing-based MAD office

"If you're not in China, you're not playing the game"

Lester Thurow

In 1997, while attending university as an undergrad I sat attentively in what was perhaps the biggest lecture on campus. Rem Koolhaas had come to give his seminal lecture on China. A lecture that would eventually become not only a radical book, but also a glimpse at the present and future condition of the Now. As Koolhaas spoke of the unparalleled rate at which Chinese architects were building in comparison to their British counterparts--conjuring images of two Chinese architects designing a 50-story building in their mother's kitchen--it left one to wonder if Chinese architects are the most productive will they also become the most prolific?

In 2006, a group of young, mostly Chinese, architects working in China accomplished a feat most young architects can only dream of: MAD office won an international design competition to design a 50-story residential tower in the edge-city of Mississauga, Ontario . But not only had they won it, they had become the first Chinese-based architects to ever win a competition outside of China which made them instant media darlings. Now with several other international projects under their belts, MAD is poised to become the first international and global Chinese practice: opening an office in Tokyo and beginning projects in South America and Denmark. In light of such dramatic strides and other recent developments in China's global position, one is left to wonder what happens when the Chinese start playing the game back?

I caught up with MAD office's Yansong Ma, Yosuke Hayano and John Phoenix this past October at the Twisted Tower conference in Chicago.

(0:00) JOURDEN:// Welcome to Chicago, have you had a good time at the conference so far?

(0:10) MA:// Yes

(0:11) HAYANO:// Quite interesting

(0:15) JOURDEN:// Basically, I just wanted to start out by asking how the firm started. And then move on to more specific projects that you've been working on.

How did the name MAD come about? Why are you guys MAD? And how does it inform your work if it does at all?

(0:36) MA:// Before we met in London, I registered a company in the United States after my school. I wanted to start something, but at that time we didn't have anything to do. So I registered MAD not even sure if we'd be doing architecture... (laughs)

Later, when we met in London we managed to do some competitions in China. So we won a few competitions, and this company then became a real practice. Then we moved back to China in 2003””now we have a space and people to go forward with...

(1:28) JOURDEN:// I see, so it started out in the States as a sort of idea toward the practice, and then you met in London where...

(1:35) HAYANO:// At that moment, we were still working for Zaha Hadid . After that we moved to China and became independent.

(1:50) JOURDEN:// So was there a moment--cathartic moment or something that actually prompted you to decide that the moment was right to open an office. Was it what was happening in China at the time?

(2:06) MA:// In China, it's always a good moment to start--there are a lot of opportunities. Because the work we are doing is quite special--architecture--changing a lot in this context [China]. Like I said in the lecture, for the first two years we did many competition--sometimes we win, but these never got built. And these were proposals that we spent a lot of time and energy on--this is very rare in China, because every single architect is building a lot of square meters. But we still remained confident to develop our ideas.

The Toronto Tower --the competition we won there, changed the whole situation, now we are quite famous in China and we have the right to speak--people now believe in us, and many important clients come to give us commissions. So this was a turning point.

The Absolute Tower, Mississauga, Canada (completion 2009)

(3:20) JOURDEN:// You explained that you were working on competitions, but was that the main focus of the firm when you guys started up? Or was there already a work base you could tap into in China and then do these competitions on the side? How did it work?

(3:45) MA:// I think for young offices there are just two choices. One is taking small commissions like small private houses, and the other is entering open competitions. But in China private property is not as prevalent like in Western countries. A lot of big developments come from competitions, so we do have choices to do competitions. After we did a lot of competitions people already knew us for our divergent imagination--they like to show our proposals and not building them. (laughs)

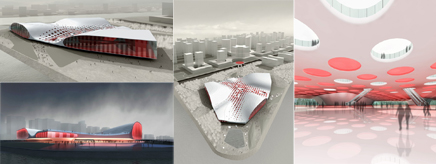

Hong Luo Club House, Beijing, China (2006)

(4:28) HAYANO:// A lot of people talked about our projects, but never to build, they just come to ask you to design.

(4:35) MA:// But after Toronto people think their image--the building rendering--can be turned into reality. Developers believe they can build them and make money, so it changed the pattern for us.

(4:49) HAYANO:// We didn't change, but people changed their minds--their attitudes in China. Once people started to believe in us we had a chance to make it.

Changsha Culture Park , Changsha, China (2005)

(5:00) JOURDEN:// So once you were able to cross that bridge there were many avenues you could choose. This sounds like a lot of young firms; once you make it over that first hurdle then it sort of ices the deal.

(5:10) HAYANO:// Yes.

(5:12) MA:// Actually, this one [story], is the first time a Chinese practice has won a competition outside of China in history--it became national news and not just architecture.

(5:25) PHOINEX:// When I would go to China every month, and when I would go to a hotel--and they [MAD] didn't even know it, there would be a magazine with a picture of Mississauga in it--magazine after magazine after magazine. They become incredibly well known very quickly. Now, I think if that building had been in China, they wouldn't have gotten the same press.. They would have got press, but to compete against ninety other architecture firms globally and to win being the first Chinese firm to ever do so is amazing!

Just to give you a scale of what's going on in China, The Vice-Minister of Construction, the number of people coming under him is fifty-five million. So it's quite something that he knows this firm. And I don't know how many architects there are in China. How many are there? (collective pause as everyone attempts to decide--1000s?!)

The Absolute Tower, Mississauga, Canada (completion 2009)

(6:36) JOURDEN:// In terms of what is going on now with Chinese architects--you have Yung Ho Chang taking over at MIT and Qingyun Ma from MADA Spam is now the dean at USC, do you see this as sort of a full realization of Rem Koolhaas ' statement about how much Chinese architects were working in comparison to their Western counterparts?

Is this the culmination of those efforts, or is there something more coming? For instance, Architectural Record is chiseling in to have their own issue there; there is this whole lean to look at China as sort of a panacea for capitalism. Now you actually have Chinese architects being "exported" out! What do you think about this new trend?

(7:32) MA:// I think it's not only the architecture field. Also, its economics, mathematics, and art...

(7:38) HAYANO:// The art scene is very exciting there.

(7:42) MA:// The art scene is so focused and many people are emerging. Maybe all of these American institutions want to have a larger international presence by including Chinese intellectuals.

I think Yung Ho Chang is a very good educator. I think he is the first Chinese architect educated aboard in western modern architecture who came back to China to practice...

(8:13) JOURDEN:// But his father was an architect too, right?

(8:15) MA:// That is not contemporary architecture though. He [Chang] started contemporary architecture in China, which is also associated with modern architecture. It was quite new to China. But I think it's a pity he didn't continue, because he was a dean at Beijing University . The architecture program there is quite new and needs to develop more. Beijing University needs him more than MIT. I see it more as a personal choice--not as a China export...

(8:55) JOURDEN:// At one point during your presentation, you talked about the latent subversive element in your work--the sort of conceptual underpinnings of your work--where you're actually trying to question ideas about society and ideology. An example would be your 800-meter skyscraper project, just as that building literally flips on to itself, it also sort of takes branding and integrates it into the whole concept of the building.

Is that what your after, this effect of torsioning these different forces of media, branding, and architecture into a concept that presents itself as fulfilled totality, so that people can extrapolate some meaning...Like the number 8 for instance. You use 8 greater than 1 (8 > 1 as descriptive diagram). The number 1 being the typical office tower typology and the number 8 is how your building actually functions. But the actual number 8 has symbolic meaning in China and Asia, as lucky number so was that intentional or is that a later additive?

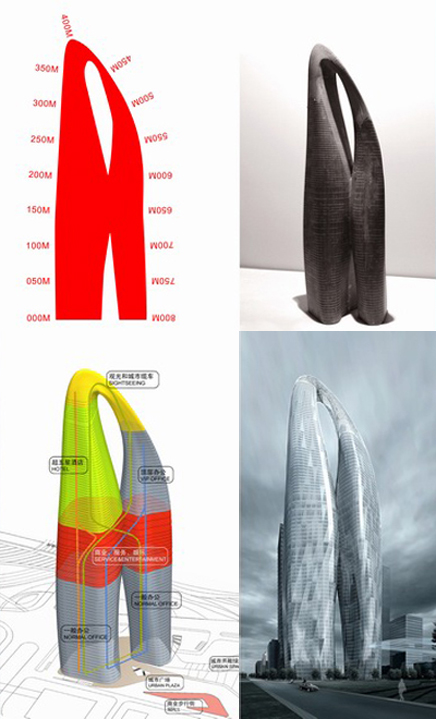

Guangzhou Twin Towers, Guangzhou, China 2004

(10:09) HAYANO:// It's a later additive. But I think the idea is the intent to communicate with a range of people, not only architects who can understand our proposal. It's quite important to give [people] an idea of what the concept behind the building is. Now days a building is more for the people who don't have any idea about concepts of space or form. It gives them a point of reference from which to launch into an understanding of these principles and gives them an opportunity to start to develop an interest in ideas of space and form. I think this is what we are actively pursuing when we engage in these types of tactics.

(10:40) MA:// I think in context to the West, people have already passed this social debate--about hierarchy and the social. They [the West] have already talked so much about technology and how to realize things, but in China it hasn't reached that level yet. All our work uses the project more in the context of contemporary art--more critical--very critical to social issues. It's very sensitive. We like to discuss these architectural concepts in terms of Chinese social issues.

Guangzhou Twin Towers, Guangzhou, China 2004

(11:29) JOURDEN:// When you say social issues though...some people might...China has a unique situation going on, right? Where it's rapidly--obviously you know--rapidly changing and you're [China] basically, arbitrarily, I would say, creating a middle-class structure in urban areas and people from the outlying rural areas are becoming a larger working-class. I don't know, that is sort of interesting development that is occurring. Is that something you're interested in attacking? Or is your work mainly focused on this emerging bourgeoisie class in China?

(12:11) MA:// We put more emphasis in the context of an urban environment, which is both political and spatially dynamic. For instance, we designed not just tall buildings, but smaller urban structures like housing or landmarks. We also engaged in some purely urban projects; we designed a project for Beijing 2050. Chinese architects never designed for the future.

In this proposal we change Tiananmen Square from the vast open public space and change it into a forest. Basically questioning open space public space. We like to propose this type of question. For example, this 800-meter tower is just trying to be critical. And when we are showing the project to the public, they will ask, “this is for the tallest building! Why did you choose this?” But then in the presentation they see that being tall is not so important in the context of the city. This in turn creates a discussion. From the very start we didn't enter that competition to win...

Beijing 2050, Beijing, China (2006)

(13:35) JOURDEN:// I like that explanation. It's a good way to get at other issues through architecture.

One of the things I really like about your work in comparison to other Chinese architects working today--we already talked about Yung Ho Chang and hinted at Chinese contemporary art leaving China and having a global emphasis--but I think there is an interesting thing that happens with that. There is sort of prescriptive expectation of what Asian and East means, where as your work doesn't--like Yung Ho Chang for instance--his big thing at the Venice Biennale a few years ago...

(14:35) MA:// Bamboo...

(14:36) JOURDEN:// Yeah right, urban bamboo or something...and there was some real penetrating criticism about this, that questioned it--saying something like 'are Chinese people always pandas?'

(14:45) MA:// You know a lot! [laughs]

(14:46) JOURDEN:// Yeah? In terms of that how do you see yourselves as Asian architects working in China, but also, perhaps as the first global Chinese practice?

(15:01) MA:// I think China has grown very fast. And China is facing very distinct challenges, which are not the same as what Western society faced. This gives China the opportunity to create a unique solution and do something categorically new for the future. In China, we describe the Chinese tradition--the older generations they understand this tradition as very symbolic--bamboo, courtyard, et cetera. But our understanding is that maybe Chinese tradition is invention! Change the old conventions. The first man who tried to fly was a Chinese and he jumped from the wall with man-made wings...and this spirit doesn't exist anymore in China. If you understand this story as part of the tradition then perhaps there is something for the future. If we continue the old thing maybe our grandmother and grandfather think we don't respect them, because we are just repeating the past...I think there is a chance for us, the new generation.

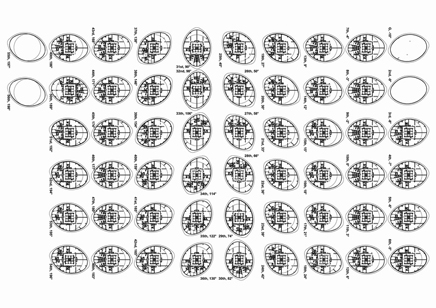

The Absolute Towers, Mississauga, Canada (completion 2009)

(16:46) JOURDEN:// In terms of your "Marilyn Monroe Building" or "Absolute World Tower" in Toronto, where did you see the trajectory of that project going when you made the top six finalists? Did you think that you would take it?

(17:05) MA:// When we saw the final six we were quite sure. [laughs]

(17:08) HAYANO:// Yeah, yeah at that stage we were...

(17:15) MA:// Some people from Canada they ask us, “How is this building Chinese? Because you are Chinese architects, and its not related to an Eastern tradition.” But later we realized that this building has a feeling of an Asian sensibility, because it's quite simple. And all the structure is hidden, unlike a western strategy, which when they are building higher they try to show the structure and challenge the structure. But with our project you can only see the lines and a change in form.

(17:55) HAYANO:// It's has a calming effect as well...

(18:00) MA:// Very calm and simple. And I think that feeling gives people--it really touches their hearts...

(18:08) JOURDEN:// I'm sure that it touched your engineer's heart too! It has a complexity to it, but it also has simplicity in its function in terms of the structural system. I think this is a good approach.

The Absolute Towers - Floor Plans, Mississauga, Canada (completion 2009)

(18:20) JOURDEN:// Do you think working for--I hate to bring where you worked into this, because you seem to operate on your own terms, but there seem to be some elements from your pedagogical relationship to Zaha [Hadid]. How would you describe that relationship now that you're on your own? Do you think her influence is clear in the way you work?

(18:51) MA:// We don't mind that people say we have a certain similarity to Zaha, because we are quite young and we are establishing our own style. During this last two years we have been trying to understand and create a way of working and thinking--this drives the need for developing our own unique language. Now I think we are pushing our designs much further than we did in Zaha's office. Plus we will build a high-rise before Zaha will... [laughs]

(19:42) JOURDEN:// I wonder if you guys are the first--you know how Koolhaas has like his sort of "children", all these different people who worked for him and now have started their own offices--it seems as though you guys are the first children of Zaha?

(20:00) MA:// What we learned from Zaha is that she hates young people who want to become her. She encourages young people to become their own self. What we learned from Zaha the most is that she was able to keep her interests live for a long time and didn't care what other people thought. That is the most important thing we have taken from her.

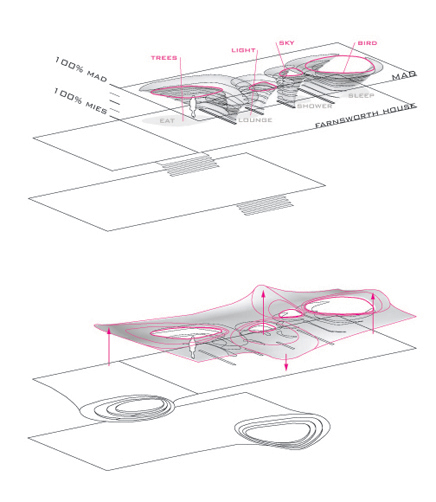

Diagrams for Denmark Project

Creative Commons License

UpStarts is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.5 License .

/Creative Commons License

3 Comments

we just published the Hong Luo Club House in http://www.plataformaarquitectura.cl

Amazing project, MAD is definitely an office doing a great job.

the two guys look MAD, but the girl looks happy. what's her secret?

OFFICE?

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.