by Nam Henderson

One beneficial result derived from the public's growing familiarity with the phrase “green design” is a renewed examination of what defines green or sustainable design. Within the field of architectural design and construction, this prominence has inevitably prompted a conversation on the nature of sustainable architecture. The proliferation of superficially and systemically “green” buildings during the past decade has also spurred this dialogue. Specifically, I am referring to a range of normative practices including the use of green roofs, green walls, wind turbines, various integrated energy and graywater systems or solar panels, as well as industry standards like LEED, SITES, or BREEAM.

Whether employed virtually, as in the case of student and professional renderings, or spec’d for the newest institutional or private project, such normalization can assume the appearance of a trend. As Allison Arieff declared in an interview last year, this is not the best frame, “Trend is the wrong word. Sustainability suffers when thought of as a "trend," as it equates it to a passing fad. The "trend" that will really shake things up? Necessity.”(1)

On the one hand, it is exciting to witness a large-scale, consumer-driven market for such green design; but it can also be legitimately criticized as marketing veneer, mere “greenwashing” intended to entice the credulous masses. Indeed, it is easy to argue that any claim of green design warrants a more critical assessment.

Towards the end of last year, I had the opportunity to spend about two weeks in the San Francisco bay area. While there, I visited a number of architectural highlights including Frank Lloyd Wright’s Xanadu Gallery, the new California Academy of Sciences by Renzo Piano Building Workshop, the San Francisco Federal Building by Morphosis, as well as the De Young Museum by Herzog & de Meuron Architekten. Moreover, I had the chance to meet with architect David Hobstetter, of the local firm KMD Architects. My conversations with him were occasioned by the construction of 525 Golden Gate, which opens this summer. The building is a KMD project for the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission and it has been touted as “San Francisco’s Greenest Office Building”.(2)

In his work for KMD, David Hobstetter dedicates his attention towards three key areas: the design process, the appropriateness of the design with its urban context and natural environment, and the symbolic expression of building function. Our conversations provided an opportunity to question him about green design, sustainability and the relationship between a building’s visual form and performative nature. He also addressed the three foci listed above and how they contribute to a project's final form.

I began by inquiring about an earlier Arch Record CEU essay(3) on a project which focused on the internal systems and engineered aspects of the building, rather than the aesthetic/design considerations. I wanted to give him the chance to highlight a more formal aspect of the building’s more noteworthy designs. Our discussions are recorded below.

David Hobstetter: Actually it’s appropriate to start with the structural frame of the building, particularly given that the site is in California, San Francisco, near major fault lines. The building construction also has an enormous carbon footprint so if the building is lost, recreating it is going to be an economically and ecological expensive proposition. So, that is sort of the starting point for the project. And within the LEED program, it's interesting there really aren't any measures regarding structural performance. Most USGBC projects within the US don't exist on earthquake zones. At some point, it will have to have, a more tangible connection to the challenges faced in a seismic zone like California.

Nam Henderson: From my reading of the Architectural Record piece, the term "self-healing frame" struck me as curious. Was that feature a result of an over-engineered or innovative, efficient design?

David: This might get a little overly technical and engineering-focused, but originally the project was going to use a steel frame. There was an alternate proposal put forward by this engineer who wanted to do a concrete framed building that has concrete shear walls running vertically through the building. We actually anchored some additional post-tensioning cables into the basement slab through the vertical shear walls. If the walls move in an earthquake, they will tend to recenter themselves. If there is a failure in the concrete along those lines, you may have to go back and chip-out the spauled concrete. The good thing about that situation is you can see and repair the failure. When a steel building fails, it doesn't come back.

Nam: With this engineered aspect of the project playing such a prominent role, the obvious question is whether the engineering compelled the form? What is the relationship between the engineering and design in terms of form and process. Does KMD use an in-house model with a cross-disciplinary studio or an outside consultant?

David: Well, in San Francisco, you have highly prescriptive rules for height, mass, bulk. We are on the northern edge of the San Francisco civic center. In fact, around the building there are rules on sunlight access to open space. On the north side, you can note the northwest side is canted, slice at an angle. That is not an arbitrary aesthetic design, that is to provide daylight to a playground space a block away. During proscribed hours designated by the City of San Francisco.

Nam: It sounds like a design based on a mapping of pre-defined restrictions not focused on formal iteration.

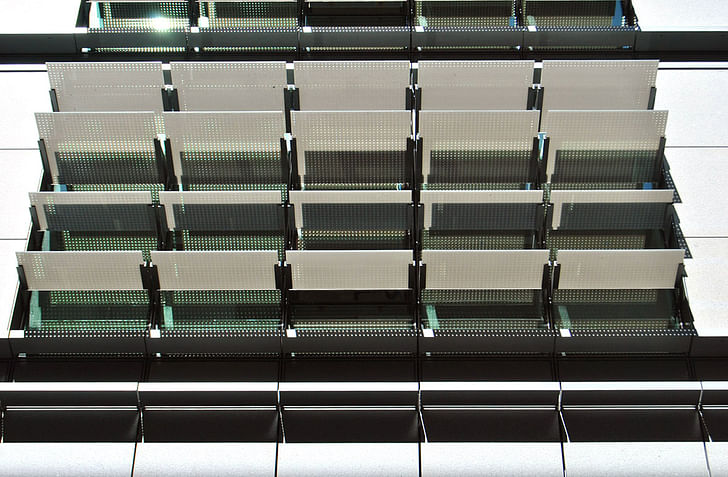

David: It's a very constrained neighborhood. We had guidelines for materials including the type of stone, "Sierra White Granite," but we didn't take a historicist’s approach to the design. The building is a modern expression of architectural principles. Those are largely environmentally driven. The north side is shaped with the wind tower to funnel and focus air in the slot between the vertical wing and the side to drive the turbines. The south side has a lot of screening which is responding to the sun. The east and the west sides have less windows because of the difficulty, particularly in the West, of controlling the effects of solar heating and glare.

Nam: The shading devices on the south are fixed. Is that a direct result of environmental, economic or design concerns; in other words, was it a data, ecologic or aesthetic driven decision?

David: Backing up a little bit, all the major building systems were studied from a life cycle perspective, a cost benefit angle. We looked at operable and static sunshades. The operable ones didn't pencil out. We have a combination of fixed horizontal shading, high-performance glazing and some interior shading on solar responsive controls. The jury is still out on operable sunshades, the maintenance, equipment to run them, we took an incremental approach.

Nam: Would you agree there is a tension in contemporary architecture regarding the forms of sustainability? For instance the difference between high tech vs. low tech or passive vs. active. From siting and thermal considerations to high tech automated approaches. Is a resolution as simple as a full cost benefit analysis? Does green design mean that every project has to include a green roof, green wall, etc.? A turbine or two, perhaps. Are these signatures of authentic "greenness"?

David: Number one, the PUC had a mission of pushing the envelope in green technology. They wanted the building to be an expression of their commitment to resource conservation. PUC has a very aggressive program in that arena. So all the systems were looked at in terms of cost and payback. The PUC wanted to go the extra mile, say, compared to a developer or someone, that just wants to know payoff in terms of years. They were also looking for ways the building could become an educational piece for the community. So it is designed to make you realize this isn't your run-of-the mill building for graywater treatment (ed. for more information on Living Machine systems founded by Tom Worrell go to www.livingmachines.com). The turbines will announce that, then in the lobby, we have a Living Machine.

Nam: I wanted to ask you specifically about that. The idea of sustainability seems to require some idea of a design’s ability to serve as an educational tool. Will the Living Machine actually handle all the gray and black water?

David: Yes, all of it.

Nam: So it’s not just educational but also fully functional?

David: It will be reused for irrigation and flushing, not drinking water standards. The Health Department wouldn't go along with that. Part of the educational piece is just the various agencies. It's not off the shelf - it's customized.

Nam: I was reading KMD's website, and the idea of a holistic approach is described under the rubric of sustainability. Doesn't this include a pedagogical educational element; educating your firm, the local agencies, the public? So sustainability is applied not only in a mechanically performative sense but as a level of social design. Is that an intrinsic part of this project?

David: Absolutely. Within the lobby we will have an array of flat screen monitors, which will broadcast the mission of the PUC. We have even talked about wiring the solar or wind hardware up, so we can provide metrics of energy production vs consumption.

Nam: When you begin thinking of sustainable design in these terms, does it inevitably translate into valuation or metrics? Post-occupancy studies, usage data?

David: It is absolutely imperative, especially with public sector projects like this, that the building design exists within the realm of a research-design-evaluation cycle. This is the essential element of an intelligent design process. One thing we have kind of been focused on here has been energy consumption and education, but both of these are subsets of the most critical issue to me, which is optimizing human performance in a built environment. By providing optimal daylight, fresh air, invigorating work spaces. So you can work at a measurable level of higher efficiency. All sorts of studies have shown you can do that. When you look at the costs of doing a building, not just the bricks and mortar, but the people that occupy the building, if you can achieve a measurable level of better efficiency, you pay for the building overnight.

Nam: In regards to factors like less sick days, lower VOCs, better morale, all of which point to a growing area of interest in the design community, what is the relationship between public health and the built environment?

David: Studies have shown that providing windows and skylights to workers as opposed to a static environment, does impact worker productivity.

Nam: As a designer, how are you able to convince a client to build a better project? Again, my one concern is that when we start employing data and metrics like efficiency and productivity, we are losing something.

David: At the end of the day, buildings are cultural works of art and therefore the outcome does need to be intrinsically beautiful. I do believe that if you are thoughtful about your program and the client's needs, understanding the city and land you are on, you craft a building responsive to these elements, and it will be beautiful. Buildings that drive me crazy are ones that just have too many layers. To make it look formal or impressive. You see it a lot with buildings trying to be historicists.

Nam: Is it the age old argument of ornamentation vs minimalistic simplicity perhaps? Form over function? Function includes performative concerns or various site constraints. Personally, I have a problem with anything extraneous. Even in terms of sustainability, I think the same argument can be made.

David: On the other hand, I think you can go too minimalist. A design that doesn’t talk to you about the building or where we are as a society.

Nam: I would like your professional critique. My local utility company, GRU, is completing a new project which will relocate most of the facilities type, back-of-the-house side of their operations from a downtown site, the urban core, to a new larger site located more in the urban edgelands. This project, along with many other recent local projects, will achieve some high level of LEED. They are pitching this project as a post-industrial greening and revitalization effort for the urban core. They have already branded the new district as the "Power District." What are your thoughts on the question of whether such a project can be sustainable or green? In terms of more miles traveled or the carbon footprint of new construction, as you mentioned earlier?

David: I know what you are getting at, and yes, when you get outside of the urban core, it does create certain concerns. That is actually why all the LEED emphasis on core development is great stuff. With our building, we only had so much sq footage. So we knew, certain back-of-the-house programs would be located off-site. This building is an office space.

Nam: Inevitably, it seems that one must think in terms of scale. There is LEED for the site, LEED-ND for the neighborhood, and even for the Sustainable Sites initiative for landscapes.

David: Sustainability is at the forefront, mother and apple pie.

Nam: Moving away from the green design aspects of the project, can you describe the design process?

David: Starting with a really thorough statement of program and objectives. Then looking at multiple options to solve a problem. Not just for the overall project but even pieces of it. The decision are made from the best judgements of the stakeholders. For instance, with the sunshade, there are more than a few ways to sunshade a building. Looking at pros and cons, some other criteria include: is it harmonious with not just what we are doing but the larger context?

Nam: There seems to be an interest in modularity or swapability with regard to technical systems. For instance the turbines?

David: Turbines are not very advanced in terms of a building technology, so we did think about the need to replace them as the technology advances.

Nam: Again, there is that idea of what is more sustainable: "not having to tear down the building or build a new one", or being able to adapt it over time?

David: Exactly, we are hoping turbines, as they get more efficient, can be swapped out.

Conclusion

I would suggest that the above interview clearly lays out the parameters for expanding in some concrete (pun intended) and specific terms the definition of green design. In the process, David Hobstetter also provides some evidence for the claim that 525 Golden Gate is “San Francisco’s Greenest Office Building”.

Significantly these involve, thinking more comprehensively, perhaps about how a building can be sustainable. Beyond just the literally greened (green roof, green wall etc) building. Concerned instead, with an idea of resilience. The idea of resilience has obvious biological metaphors built in, but even in a purely mechanical or engineered sense, it is notable. Take for instance the resilience of the concrete structure, which can be repaired or patched after an earthquake.

If being sustainable also involves sensitivity to site and context, local climate or geography, than building a seismically resilient project in San Francisco seems inherently greener than not. Moreover, there is the systematic way in which the various decisions from the inclusion of the turbine, to Living Machine, or operable vs non-operable shutters were considered. Including, LCA, their educational or social design implications, their modularity and interchangeability, all of these factored into the decision-making process.

Moreover, there is the dual use of both passive and active techniques in the design. Fresh air will be delivered by a full-height, curved glass chimney that rises dramatically and visibly along the main foyer, exploiting the stack effect to cool the space at every level. Passive sun shading is employed. Yet also the turbines and a Living Machine. In each case, the techniques used impact not only a green design metric but have some formal or visual element.

David is not alone in making the case for the inherent greenness of a resilient, engineered concrete structure. According to ASLA’s The Dirt, at 2011 GreenBuild, Ronald Mayes and Leonard Morse-Fortier, engineers with Simpson Gumpertz & Heger, contended “that no matter what level of green certification a building achieves, it shouldn’t be considered green if it isn’t earthquake and wind-proof. Currently, most buildings, even green ones, are simply designed to protect people and don’t survive structurally, meaning all that material is wasted. Using ‘performance-based design’ approaches, buildings can be designed to survive major earthquakes and storms...He also called for ‘seismic resilience’ to be adopted by LEED, perhaps as regional credits in earthquake-prone zones.”(4)

Finally, what of a concluding argument? The key point I think is that seismic integrity and the general lifecycle/longevity of a building should be a factor in any consideration of how sustainable a project is. Now obviously, like all good architecture and any true example of sustainability, this should be considered contextually. Meaning, if a building is not located in a region of seismic activity, then seismic resilience doesn't need to be as heavily considered. It should be readily acknowledged that LEED and other ratings systems are not static measurements but are living documents that are constantly being revised. For example, the period for public comment on LEED 2012 draft changes to the rating system just closed, and the revisions will be voted on from June 1-30, 2012. If not in this version, hopefully a future revision will look at the arguments laid out by David Hobstetter, Ronald Mayes and Leonard Morse-Fortier and adjust the ratings systems accordingly.

Footnotes

1 - http://www.theatlantic.com/life/archive/2011/10/a-conversation-with-allison-arieff-writer-and-editor-on-sustainability/246440/

2 - http://inhabitat.com/san-franciscos-greenest-office-building-tops-off/

3 - http://continuingeducation.construction.com/article.php?L=5&C=799

4 - http://dirt.asla.org/2011/10/12/8612/

An ex-liberal arts student now in healthcare informatics, I am a friend of architects and lover of design. My interests include: learning/teaching, religion(s), sustainable ecologics/ies, technology and urban(isms). I was raised in NYC, but after almost two decades of living in North Florida I ...

4 Comments

Thanks Nam, Great Article! I wrote a lengthy research paper about the construction of this project by Webcor. The vertical post tensioning system and the seismic technology in the building, developed by Tipping Marr, is very innovative. Slip plates allow floor slabs to move independently of cores if necessary, and the vertical post-tensioning/gargantuan mat slab that enable immediate occupancy in a design-basis earthquake were fascinating to see put into place.

The Building Dancing in an Earthquake

I would love to hear more about the reasoning behind the new building and the needs for the new structure ... the greenest of all would be renovating or expanding their existing office space with some upgrades ... was this not possible or considered? particularly of concern since almost every project I work on in SF has a PUC charge that donated to this (in my opine rather mediocre) project.

ryan couldn't agree more with the idea that rehabbing/upgrading a building is preferred and generally more efficient and culturally/contextually sensitive than building a "new" one. that is why I asked David about my local utility companies "regenerative", "livable" and "sustainable" plans to do just that...

as for this project, you may feel that the project is mediocre but at the same time they are some like Michael who think "The vertical post tensioning system and the seismic technology in the building, developed by Tipping Marr" are "very innovative"...

So i suppose it depends on your perspective. What do you think about the specific issues brought up re: LEED certification/point system and seismic proofing?

I like the LEED and seismic upgrades, I'm all for technology ... I'm hoping the PUC uses their expasion into new building to expand water conservation, and not just BAU.

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.