The one thing you will not find in school--or even on Architecture Registration Exams--is a course on how to get work, yet it is one of the most basic needs of any design practice. In fact, if you don't have an equal ability to experiment in getting work as you do in doing work you would be fortunate to make it past the first five years.

UpStarts is a series of features on the foundations of contemporary practice. It will have a global reach in which practices from Europe, North America, Asia, and beyond will be asked to address the work behind getting the work, and the effect of cultural contexts. The focus will be on how a practice is initiated and maintained. In many ways, the critical years of a fledgling design partnership is within the initial five years, after the haze and daze of getting it off the ground. UpStarts will survey the first years of practice as a tool for tracking the tactics of the rapidly evolving methods for sustaining a practice.

Archinect's resident landscape architect Heather Ring stopped by the studio of the landscape collective NIPpaysage in Montreal and chatted up-start with 3/5 of the NIPs: Mathieu, Josée and Michel.

When did you start collaborating?

Michel: The typical speech!

Mathieu: The genesis!

Michel: In '97 and '98, as classmates, we started doing some competitions - not the five of us, but in pairs, in different groups, mixed. Mélanie and I were selected to design a garden in Chaumont, France. There we met Michael Blier - who had worked at Martha Schwartz (now he runs Landworks Studio in Boston), and he invited Mélanie, France and myself to come work for Martha. Mathieu and Josée were working in eastern Canada at the time, but soon came to work in the States as well. So the five NIPs were there, working in different offices, and doing competitions at night -- when we had time.

How did you manage to moonlight competitions while working at such intense offices?

Mathieu: It wasn't always easy to find time, but it was more fun to moonlight for ourselves. We were sometimes tired but mostly happy and enthusiastic because it was for our ideas.

Michel: But we are officially no longer moonlighting. We are full-time in the office.

The NIP Office.

When did that switch happen?

Michel: In 2001, our garden proposal was picked for the Metis Garden Festival , and Mélanie and I left our jobs and went up to Quebec to build it. We then started the office in our living room in Montréal.

Josée: Six months later, France came back from Martha's and a year and a half later, Mathieu and I came back from Boston as well.

Michel: And then we were five.

Mathieu: We all came back to Montréal gradually, which allowed the firm to grow slowly instead of having five mouths to feed overnight.

How did you know it was time to start doing your own thing? Did you have projects on the table when you came back to Montréal? And did you have any models for how to set this up?

Mathieu: We really didn't have any idea what we were getting into. It sort of felt like the right thing to do and the time to do it. We didn't have much experience, but we had architects back in Montréal calling us to collaborate on competitions. Having worked for a few bigger firms, we developed our own firm as a scaled down version of what we felt worked well in large offices. It was during the summer of our first garden built at the Metis garden festival in 2001: with the great visibility this festival brought, we were on a good wave to begin.

Josée: When we did the Metis garden, we realized we had to find a name. We picked NIP. I think NIP was really born there - we found we really enjoyed working together and started doing other competitions.

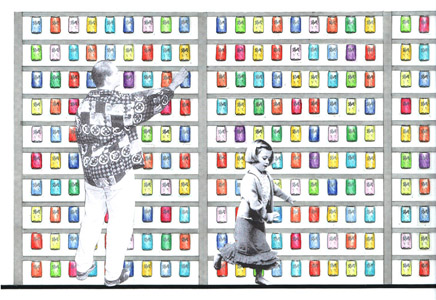

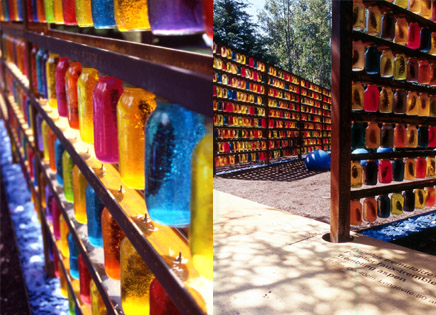

In Vitro, MetÃs Garden Festival, 2001.

So where did the name NIP come from?

Mathieu: It was a very long e-mailing process (we were working for three different firms in Cambridge at that time) that took a week or more. We made the final decision around a table and a few beers around midnight. We wanted something nice and short that made sense for us. “NIP” is the French acronym for “Personal Identification Number,” which is a short catchy word that everybody knows. For us, NIP is about each site's personality and identity. It is deeply rooted in our approach and the way we perceive of our role as landscape architects.

Michel: You always need your NIP, your ID number.

Did you find there was a shift in the way you worked when gave yourselves a name? Was there a difference between collaborating and being a collective?

Mathieu: There was no collaboration prior - we were automatically a collective.

Michel: A lot of people don't understand how we work because we're all equal in the office in terms of developing ideas, meeting with clients and administration.

Mathieu: Design is done always as a group. We never leave and say “Design on your own and then come back.”

Josée: Well, we do that sometimes! We meet and develop a baseline orientation for the design, separate and do our own things and then meet again.

Mathieu: Right, but most of the design really happens around this table - together. Compromise is never an option for the basic idea. We usually agree pretty quickly, but sometimes, it takes a while. When there is a moment that all of us are hesitating, we just put it to the side and talk about it the next week. We all know when it's “the one.” We can all feel it when we have something good.

Do you each fall into particular roles in the collaboration?

Josée: We all have our interests and strengths, of course. But, it's funny, it used to be that the person who answered the phone was project manager of that job. All coordination became the task of that person and they ended up in contact with the client.

Mathieu: Delegation is one thing we're learning as we grow. You can't know everything about all aspects of the jobs. Before, we knew everything about every single job, whatever it was. It could have been super-technical --

Michel: Now roles are generally assigned naturally, depending on schedule, workload and interests. Design is something we always do together. We will sit and talk and sketch, exploring ideas. But it actually made a huge difference when we had a separate physical space for the office.

So where do you see NIP going? Do you see NIPpaysage as an entity unto itself, or is it dependent on the dynamic of the founding members?

Josée: I think for a very long time, we felt a landscape studio with five associates was big, at least in Montréal. We were quite happy doing the design process from one end to the other. But we're going to be confronted with this question very soon, as we've been getting busy and are thinking of hiring. We had one student helping us this past semester, and found it really hard to include him in the design process -- to let him jump into our bubble. It's not as though we're closed to the idea, but it's going to be a challenge. If someone comes to work with us, they're going to be interested in designing, not just being a CAD-monkey. And we want to offer that opportunity, so we are going to have to re-organize in some ways to allow NIP to grow.

Michel: We work very closely, we've been able to develop techniques to pass back-and-forth drawings very quickly.

Mathieu: People are surprised that I can take a drawing that someone else is working on and draw on top of it. There's no shyness about our creative process.

Michel: It's very honest.

It seems like some of your first projects were more flexible collaborations - pilgrimages of sorts. I'm thinking, for example, of the Nomadic Landscapes and the community design-build projects in Ecuador.

Mathieu: You paired those projects together?

Josée: That's funny because those are two projects we did simultaneously, but not as a group.

Michel: Mélanie and I did the Nomadic Landscapes. It was actually our first project since setting up the office in Montréal. It was the beginning of the real office - one of our first jobs. Josée and Mathieu went to Quito in the same summer.

For the Nomadic Landscapes, Mélanie and I were on boats on the Hudson River with other landscape architects and artists challenged to build a parterre of landscape in boxes along the shores of different cities between Montréal and New York. They were intuitive, immediate impressions of these places, using found materials. People boarded and got off the boat at different cities, so we were always working with a shifting team. Here we are so familiar with one another, but then we had to find an interesting and strong vision with strangers.

And in Quito?

Josée: Well, after working three years in the states, we felt we needed a new point of view - a social experience. In our previous jobs, we were working on huge projects with huge budgets, never in contact with the client or the people who would use the spaces we designed. When we were in school we went one summer to visit Quito, more as tourists and somewhat inspired by the work of Samual Mockbee (USA) and Teresa Montiel (Europe). We always wanted to go back. So we decided that between Boston and joining the others in Montréal, we would go for six months and build two small playgrounds for kids. We moved there with a $2000 grant and learned local construction techniques, the color palette of the south, and local materials.

Mathieu: And working with the community and local craftsmen, we built the projects supposedly with some sense of permanence.

Michel: All the early NIP projects were design-build, actually.

Paysages Nomades: Quebec ”¡ New York, 2002.

Projecto Paysage, Lamana and Quito Community Center, Quito, 2002.

Both projects definitely require a certain resourcefulness. How did engaging in the design-build process influence your way of working?

Mathieu: We were so eager to see our ideas get built! Participating in the construction allowed us to keep labor costs down and keep more money for materials, allowing us to explore larger scales, bigger installations. Our first built projects were very important because they made us realize how fussy we need to be with details in order to get good results.

But all of those built projects, with the exception of Ecuador, were temporary works. At the time we started, there were all these events where we could easily get stuff built quickly. They had small budgets - but they were willing to try almost anything. But after trying three or four or five of these, people started to think we were only interested in installations and temporary works.

Michel: But it helped us to become known.

Mathieu: It helped us survive. So there were two sides. But potential clients would then ask, “Why would we hire you to do public work when you only do temporary installations?” Impluvium, La Biennale de Montreal, 2004

Impluvium, La Biennale de Montreal, 2004

Pause, Ephemeral Landscapes, Mont Royal Avenue Montreal, 2005

So when you started to get projects of ”˜permanence' that shifted away from the temporary installation or event, how did your approach to landscape, as this temporal medium, change?

Mathieu: Not much about the landscape is “permanent.” Our work is to create meaningful spaces that offer interesting and renewed experiences. The idea of “play” is an important aspect for all our work, temporary and permanent. We're not serious or theoretical, we're happy to encourage users to interact with the spaces they evolve in. Permanence is assumed by the choice of materials, it's important that they survive well throughout the seasons. Meaning and experience require the same approach whether you do temporary or permanent work.

This idea of ”˜play,' through a kind of a pop sensibility, seems readily apparent in all your work. Though I think if I saw your recent winning entry in the Point Pleasant Park competition I wouldn't recognize it as yours because ...

Michel: It's very serious!

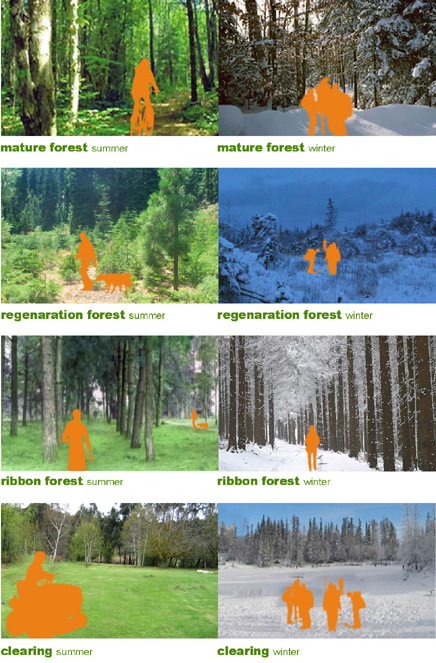

Yeah! Why is that? Do you think playfulness is something that only works at the small scale, or within a temporary installation? Does it have less relevance at the massive scale of the park or city plan?

Michel: I think this kind of playfulness can happen at all scales. But we are learning to be flexible to the client and project. We've never done a competition before at this scale or with these conservative concerns - it was a complicated and sensitive restoration project. The community was very attached to the park as it had been before the hurricane and so the design had to be minimal and the regeneration strategy inventive. Actually, between Phase 1 and Phase 2 of the competition, the main thing that changed was the graphics. They freaked out with our initial boards, so we toned down the graphics without changing much of the strategy.

Makes you wonder how much the graphics relate to the built work in such large-scale projects ...

Mathieu: Perception is really in the graphics. They are constantly referred back to and I think they really do affect the ultimate feel of the project when it's built. Our projects so far have been very similar to the graphics used to represent them - it will be interesting to see what happens with the park.

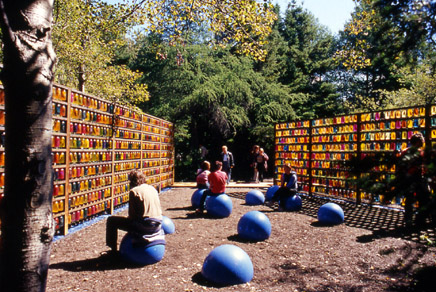

Forestification, Phase 1 & 2 Plans, Point Pleasant Park Competition, 2005.

One of your first built projects, the In Vitro Garden at Métis, deconstructs the forest as a laboratory, and the Point Pleasant Park project, Forestification, addresses a strategy for regenerating a hurricane-ravaged forest. So did your thesis for the garden inform your strategy for the park?

Mathieu: Good question. Who wants to give the forest speech?

Michel: I've got it. The five of us are from the countryside - the forest regions of Quebec - an eight hour drive from here. The forest is the landscape that connects the five of us - and one of the reasons we gravitated towards one another in school. And we weren't from Montréal ... so we had no life outside of our studio friends. The two projects talk to one another - we wanted to show people that the forest is not one idea - but multiple experiences.

Mathieu: The In Vitro Garden was a good introduction to landscape architecture. We realized that we had very different conceptions of what a forest is - and wanted to speak to people's expectations of “nature” and the human gesture.

Michel: Each forest community in the Park is like a jelly-jar in the Garden.

Forestification, Point Pleasant Park Competition, 2005.

The garden seems like such a good vehicle for young designers, as a medium of endless imagination, a gallery whitebox or a blank canvas ...

Josée: When we first started the office (we still have this philosophy) we wanted to tell stories through the garden. At Métis, we wanted to criticize the way the forest is managed. We thought this message should be sent to the people in a funny way, not to shock or be moralistic, but to provoke emotion. So if the message didn't come through, we just wanted them to be seduced by the garden. We realized it didn't really matter if they got the “meaning,” as long as they left with a strong experience.

Michel: We see the garden (and these festivals) as a place to experiment with ideas and test materials. It's a platform to give us the tools that can be applied to larger projects.

So how are you getting new projects now? Are you mostly still doing competitions?

Josée: Here it's really hard. In Quebec and Canada, there are mainly architecture competitions, not much landscape. Though, some architects invite a landscape architect, occasionally, if they want to have a more integrated project. We have made some strong connections through working on these teams.

Mathieu: We still keep an eye out for advertised work, but stuff comes to us mostly through word of mouth and networking. We've established some interesting collaborations with other consultant firms that call on us when they can. Old employers call us as sub-consultants. Since the kids came, going to lectures, seminars and exhibitions is still an option, but it's usually more difficult to talk business when you are running around the gallery, trying to catch running babies!

Josée: But this time of the year, we are very busy. In Quebec, people think we don't work in the winter, so they wait until spring to call us.

I know! I always get asked, “What do you do when it's cold out?”

Michel: People think we're landscaping in the summer and clearing snow in the winter.

Mathieu: We really like doing schools and playgrounds. They are an opportunity to channel the playfulness of our installations and create interesting spaces. And now we're actually designing the permanent entryway to the Metis Garden Festival.

Oh, I like that, considering it was your beginning as NIP.

Josée: It's permanent, but with a temporary budget!

Mathieu: That pretty much defines our office. We have a limited budget and so it forces us to be imaginative with pushing the limits of a project. We've often had to just design and re-arrange materials on-site. I can't wait for the day when we actually have some funding behind our work!

It also seems that, between the Complexes Cirque, Chapiteau des Arts and École National de Cirque, you have something of a “Circus Series” going on ...

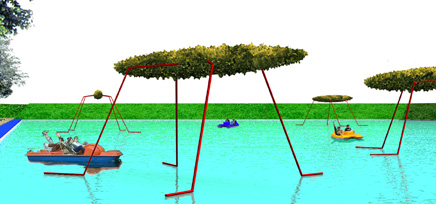

Mathieu: I guess we connect quite well with the circus “state of mind.” We have been privileged to work on many aspects of circus culture, including large-scale planning projects where the idea of landscape has been developed to whimsical and environmental objectives. Cirque du Soleil was one of our first big clients. We got the chance to really explore the way mind and body can experience landscapes in new and playful ways: you can imagine that regular site and programming constraints are very different in the world of clowns and acrobats. We have been lucky to be involved in a series of circus-related projects, a “market” the City of Montréal is working hard to develop.

École Nationale de Cirque, 2003. Collaboration: Lapointe Magne & Associés, Architects

Cirque Complex, 2001-2. Collaboration: Hal Ingberg, Architect and Birtz Bastien, Architects.

Any good stories of having a clown for a client?

Mathieu: Surprisingly, the circus clients around here are rich and successful businessmen who are also great visionaries. It's funnier to consider our safari park project, where we have to consider how much room an elephant needs to turn around for everything to run smoothly!

Nice! Last, I wonder if there's something particular to the way landscape is approached in Quebec?

Mathieu: There is a big difference in mentality, the way people perceive and conceive landscape in Canada and the USA is very different. The way people perceive landscape in French and English Canada is also different. For a lot of French Canadians, the concept of “landscape” is something completely natural and free of charge, which usually makes our work more difficult!

Creative Commons License

UpStarts is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 2.5 License .

/Creative Commons License

1 Comment

Elephant turning radius! HA! Love it.

great interview, Heather. Great addition to the UpStarts series...

...keep 'em coming...

Block this user

Are you sure you want to block this user and hide all related comments throughout the site?

Archinect

This is your first comment on Archinect. Your comment will be visible once approved.